Printer Friendly Version in PDF Format (55 PDF pages)

ABSTRACT

Many women facing opioid addiction are either pregnant or caring for children and face a number of social, structural and economic barrier in accessing treatment. In recent years, clinicians and policymakers have become increasingly interested in supporting substance use treatment approaches that provide comprehensive services to pregnant and parenting women and their family members and recognized the women's role as primary caregivers. Since MAT is the recommended clinical practice for treating pregnant women and adults with OUD, we sought to define how MAT can be combined with family-centered services. This study further examined a selection of state and local treatment programs targeted to pregnant and parenting women and their families to identify key challenges and opportunities in expanding access to comprehensive, family-centered services and MAT treatment for this population.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization. This report was completed and submitted on September 25, 2018.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. BACKGROUND

2. METHODS

2.1. Overview

3. FAMILY-CENTERED MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT PROGRAM FRAMEWORK

3.1. Program Framework

4. SELECT FINDINGS FROM A STATE PROGRAM SCAN

4.1. Statewide Initiatives Versus Standalone Programs

4.2. Eligibility Rules and Requirements Across States

4.3. Care Coordination

4.4. Statewide Initiatives for Capacity Building

4.5. Partnerships

5.1. Overview

5.2. New Hampshire Case Study

5.3. Ohio Case Study

5.4. Pennsylvania Case Study

5.5. Texas Case Study

6. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES RELATED TO TREATMENT

6.1. Insurance Coverage

6.2. Funding Constraints

6.3. Workforce Capacity Shortages

6.4. Limited Access to Safe and Affordable Housing

6.5. Provider Reluctance to use MAT

7. ADDITIONAL FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

APPENDICES

- APPENDIX A: STATE OPIOID USE DATA

- APPENDIX B: PROGRAM SCAN

LIST OF EXHIBITS

- EXHIBIT 1: Program Framework

- EXHIBIT 2: State Policies Regarding Reporting and Treatment of PPW and OUD Across Selected States

- EXHIBIT 3: Statewide Partnerships for PPW with OUD

- EXHIBIT 4: Key Dimension of MAT Treatment Programs

ACRONYMS

The following acronyms are mentioned in this report.

| ACA | Affordable Care Act |

|---|---|

| AIM | Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health |

| ASAM | American Society of Addiction Medicine |

| BHA | Maryland Behavioral Health Assessment |

| BSAS | Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Addiction Services |

| C4CS | Maryland Center for a Clean Start |

| CAP | Maryland Center for Addiction and Pregnancy |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CHARM | Vermont Children and Recovering Mothers |

| CHCS | Center for Health Care Services |

| COE | Center of Excellence |

| CRFTSAR | Kentucky Comprehensive Residential Family Treatment for Substance Abuse Recovery |

| DSHS | Texas Department of State Health Services |

| HRSA | Health Resources and Services Administration |

| KORE | Kentucky Opioid Response Effort |

| MassTAPP | Massachusetts Technical Assistance Partnership for Prevention |

| MAT | Medication-Assisted Treatment |

| MATR | Kentucky Maternal Assistance Toward Recovery |

| MCH | Ohio Maternal Care Home model |

| MCPAP | Massachusetts Child Psychology Access Program |

| MIR | New Hampshire Moms In Recovery |

| MOMS | Ohio Maternal Opiate Medical Supports |

| MOMS+ | Ohio Maternal Opiate Medical Supports Plus |

| Mothers MATTER | Pennsylvania Mothers Medication-Assisted Treatment for Engagement and Resilience |

| MRI | Magnetic Reonance Imaging scan |

| NAS | Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome |

| NFP | Nurse Family Partnership |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| OB-GYN | Obstetrics and Gynecology |

| OHH | Opioid Health Home |

| OTP | Opioid Treatment Program |

| OUD | Opioid Use Disorder |

| PAT | Parent as Teachers program |

| PATHways | Kentucky Perinatal Assistance and Treatment Home |

| PPW | Pregnant and Postpartum Women |

| Project RESPECT | Recovery, Empowerment, Social Services, Prenatal care, Education, Community and Treatment project |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| QBHE | Qualified Behavioral Health Entity |

| RTI | Research Triangle Institute |

| SAMHSA | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

| SMARTS | Kentucky Supporting Mothers to Achieve Recovery Though Treatment and Supports |

| SOR | State Opioid Response grant |

| STR | State Targeted Response |

| SUD | Substance Use Disorder |

| UNC | University of North Carolina |

| UPMC | University of Pittsburgh Medical Center |

1. BACKGROUND

Growing rates of opioid misuse and opioid use disorder (OUD) in the United States are often described in terms of overdose deaths, opioid prescriptions, and number of individuals with OUD. While these are valuable metrics that help quantify the problem, they obscure the fact that opioid abuse occurs not within a vacuum, but within families and social networks -- and these families and networks face consequences of addiction alongside the individual. Many women struggling with OUD are either pregnant or caring for children. As of 2005, approximately 70 percent of women entering substance use disorder (SUD) treatment services (for opioid and other substances) had children (SAMHSA, 2007). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicates that between 2010 and 2014, 40 percent of all adults with a SUD diagnosis were living with at least one child. Adults with SUD living with children were more likely to be between the ages of 26-50 and to be female compared to the rest of the SUD population (Feder et al., 2018). Further, about one in eight children (8.7 million) aged 17 or younger live in households with at least one parent who had a past-year SUD (Lipari & Van Horn, 2017).

Pregnancy is a particularly critical time to address OUD, as prenatal maternal opioid use is associated with serious complications for the baby including premature birth and neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Women may also be more receptive to seeking treatment during this transitional period of their lives. The rise of the opioid epidemic has corresponded to a rise in NAS, which increased nearly seven-fold between 2000 and 2014 (Patrick, 2018). Furthermore, while the overall proportion of pregnant admissions in the United States remained stable around 4 percent from 1992-2012, admissions of pregnant women reporting prescription opioid abuse increased from 2 percent to 28 percent (Martin et al., 2013).

|

What is Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)? MAT is the use of medications in combination with evidence-based counseling and behavioral therapies for the treatment of SUDs. Medications used in treating pregnant women with OUD may include:

For treating pregnant women, less is known about the safety of:

SAMHSA, Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women With Opioid Use Disorder and Their Infants (2018). |

Given the interplay of addiction, family, and pregnancy, states and programs are increasingly acknowledging the value of providing treatment to pregnant and parenting women through family-centered programs. These programs recognize women's roles as caregivers within the family unit, include their children, partners, and/or other family members in the treatment process, and provide clinical care for all affected family members. In addition to clinical treatment -- which includes use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) as a best practice for treating pregnant and parenting women -- family-centered programs include a range of supportive and community-based services. These may include child care, transportation, housing, employment training, parenting education, and linkages to financial aid and other human services programs. Family-centered programs incorporating MAT can improve pregnancy outcomes by shielding mothers from the drug use environment and engaging them in a network of support. Family-centered programs also benefit infants by strengthening the bond between the mother and infant, thereby improving infant health outcomes. However, many challenges remain for expanding pregnant and parenting women's access to family-centered programs that incorporate MAT. Issues such as stigma, unstable or unaffordable housing, lack of specialty providers, and lack of funding have been cited as barriers to treatment for women. Provider unwillingness to provide MAT to pregnant women -- either due to lack of credentialing or training in this area, bias, or a combination of these factors -- is also a common barrier.

Nevertheless, a number of states are incorporating family-centered treatment principles into MAT services and supporting innovative approaches to creating relevant clinical and community linkages. This paper explores the core components of a family-centered MAT program framework; provides an overview of state variation in eligibility requirements and care coordination; summarizes four states' individual approaches to treatment; and discusses challenges, barriers, and recommendations for future work in this critical area.

2. METHODS

2.1. Overview

Information in this report draws from three sources: a program scan consisting of an Internet search of state and regional initiatives supporting family-centered MAT for pregnant and parenting women with OUD, key informant interviews representing a variety of perspectives on family-centered treatment of pregnant and parenting women, and a review of relevant literature.

To assist in identifying state initiatives for the program scan, RTI reviewed documents describing family-centered concepts, as well as documents and websites describing relevant programs. RTI used these documents as a starting point to identify states with programs, services, funding mechanisms and policies supporting the identification and treatment of pregnant and parenting women with OUD. To more narrowly focus the search, we focused on the 21 states with women and families most affected by the opioid epidemic. This included the states with:

-

the highest rate of opioid prescriptions per 100,000 persons;

-

the highest levels of female opioid related death; and

-

the highest incidence of NAS.

The findings from the program scan were catalogued, synthesized and included in a separate report, while select findings are provided in this report.

Key informant interviews included researchers, federal and state officials and providers whose work supported family-centered treatment services for pregnant and parenting women with OUD, including MAT. State officials were drawn from agencies in four states identified as supporting programs with elements of family-centered treatment: New Hampshire, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Texas. In these states, where possible, the study team also interviewed provider representatives to gain additional perspective on the service delivery systems. Two provider researchers, nationally known for their research and provision of services to women with OUD and their children, were also interviewed, as were and federal officials supporting treatment programs for pregnant and parenting women with OUD.

An interview guide was drafted based on the primary policy questions to be assessed. Interview questions focused on gaining knowledge of the range of services provided to pregnant and parenting women with OUD; how these services are organized and funded; how states are incorporating family-centered or family-centered treatment principles into these programs; and any barriers and challenges to implementing these types of initiatives. Each telephone interview lasted 60 minutes and was followed by email as needed to verify specific points or to obtain materials referenced in the interviews. Content analysis emphasizing primary policy questions was conducted on the data obtained from the interviews. The findings from the interviews are synthesized and included in this report, while the findings from the state and provider interviews are summarized in this report as case studies.

3. FAMILY-CENTERED MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT PROGRAM FRAMEWORK

Pregnant and parenting women face multiple legal, social and structural barriers in accessing, and adhering to, treatment. Legal issues women face include the criminalization of opioid use during pregnancy and potential loss of child custody. Many state laws conceptualize OUD as a criminal behavior instead of a chronic disease which prevents women from seeking evidence-based care (Krans & Patrick, 2016). Pregnant women with OUD also face complex social barriers to accessing treatment including stigma and caregiver responsibilities. Finally, structural issues faced by pregnant and parenting women with OUD include treatment issues, workforce issues and lack of social services. Treatment issues include cost of care and limitations in insurance coverage. In particular, Medicaid has higher income thresholds for pregnant women, but the coverage extends only to 60 days postpartum for women who are not eligible through another pathway for Medicaid in the postpartum period. Not all of the states hardest hit by the opioid epidemic have participated in Medicaid expansion which could potentially benefit pregnant and postpartum women (PPW) with OUD when birth benefits run out.

There are multiple workforce issues limiting treatment such as provider bias and reluctance to prescribe MAT to pregnant women and a lack of specialty providers who are knowledgeable in treating pregnant women with MAT. In addition, regulations requiring certification limit providers' ability to prescribe buprenorphine. As of 2016, the maximum number of patients to which waivered providers could prescribe buprenorphine was 275, while most physicians could prescribe buprenorphine up to 100 patients.[1] There is reluctance among providers to obtain a buprenorphine waiver. According to the National Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment, despite extensive recruitment efforts, only about 31,000 of America's 800,000 physicians who have the potential to prescribe buprenorphine have obtained a waiver. Additionally, according to one source only a third of waivered providers actually prescribe the medication,[2] while according to another 40 percent of waivered practitioners have not prescribed.[3]

Social service issues faced by pregnant and parenting women with OUD include unstable housing, inadequate transportation options, poor employment prospects and lack of coordination with social programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Effective treatment requires a comprehensive care program framework that addresses the complex needs of pregnant and parenting women and their children.

Family-centered treatment options recognize women's roles as caregivers within the family unit, include their children and families in the treatment process and provide family-based clinical care. In addition to clinical treatment, family-centered programs include a range of supportive and community-based services that address many challenges facing women and their families: child care, transportation, housing, employment training, parenting education, linkages to financial aid and other human services programs.

3.1. Program Framework

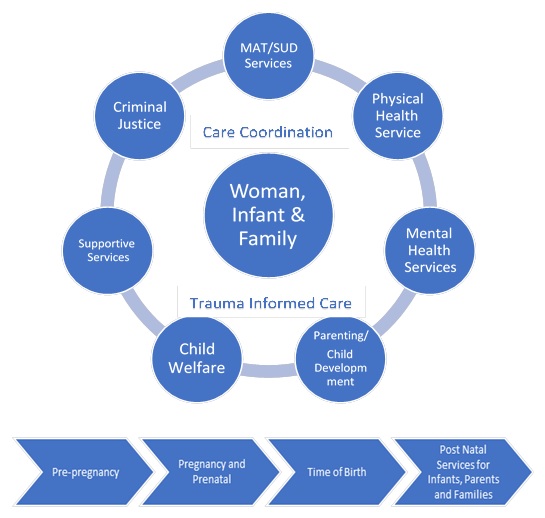

| EXHIBIT 1. Program Framework |

|---|

|

In order to order to evaluate state initiatives to provide family-centered services to women, RTI provides a basic framework for family-centered treatment for pregnant and parenting women and their children that includes elements of family-centered care, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) dimensions and levels of care, and how MAT can be included. We also include the distinct phases of pregnancy, which can interact with the elements of care. Building upon the dimensions included in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) briefings, Family-Centered Treatment for Women With Substance Abuse Disorders: History, Key Elements and Challenges,[4] Perspectives On Family-Centered Care for Pregnant and Postpartum Women: Broadening the Scope of Addiction Treatment and Recovery,[5] A Collaborative Approach to the Treatment of Pregnant Women With Opioid Use Disorders: Practice and Policy Considerations for Child Welfare, Collaborating Medical and Service Providers,[6] and the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors monograph, Guidance to States: Treatment Standards for Women with Substance Use Disorders[7] and incorporating findings from peer reviewed and grey literature, we present a framework for family-centered services depicted in Exhibit 1. The elements of the framework are described briefly below. This paper aims to describe a family-centered MAT program framework, and not a single model of care. This framework could be worked into a number of different treatment models and approaches that effectively serve populations with OUD, such as those operating under the Medicaid Health Home state plan option and the variety of primary behavioral health integration programs. The "Findings from Interviews" chapter in this report further describes specific models of care implemented in state programs that include family-centered principles.

3.1.1. Central Component of Family-Centered Care

Woman, Infant and Family. In a family-centered framework, pregnant and parenting women, their infants, other children and other family members are the central component of care. Under a family-centered framework, women would be screened, assessed and provided with on-going treatment alongside their family members. Family-centered women's inpatient treatment co-locates the mother with her infant. There is growing evidence that suggests care that preserves the maternal-infant dyad care is beneficial for both the mother and infant (Casper et al., 2014). Co-location of mother-infant services also provides an opportunity for mothers to receive education and support for breastfeeding. Recent research suggests that infants with NAS who are breastfed require less or no MAT, have less severe symptoms, and have a shorter length of hospitalization after birth (Bagley et al., 2014). Non-pharmacological care such as rooming in, swaddling, using pacifiers, breastfeeding and spending quiet time together is a frontline treatment for NAS and might be enough to treat babies with mild withdrawal symptoms (SAMHSA, 2018).

Family-centered residential care serves the pregnant and parenting women with SUD and other children under the woman's care, regardless of age. This is an important aspect of care as it has been determined that women with SUDs, including OUD, who have children are less likely to seek treatment in order to avoid separation and the fear of losing child custody (Wilke, Kamata, & Cash, 2005). Therefore, it follows that residential treatment facilities that provide integrated treatment services for mothers (those that include services such as child care, prenatal care, parenting programs, or allow children to stay with parents in residential settings) show more success than those that do not (Niccols et al., 2012).

Finally, in family-centered care, the concept of family goes beyond the mother-infant dyad to include a family constellation as defined by the woman herself. This inclusive framework may include children, spouses and partners and may also include extended family members and other close members of the community (Dallas et al., 2017). While the SUD treatment field historically sought to provide gender-specific treatment for women, which did not necessarily include fathers or partner parents as a part of women's recovery, family-centered care expands treatment to include fathers and children. This inclusion seeks to make care more comprehensive and sensitive to the needs of women (Davis et al., 2017).

3.1.2. Components of Family-Centered Care

MAT/SUD Services. MAT has been recognized as highly effective in treating individuals with OUD and is recommended as a best practice for treating pregnant women using opioids by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and ASAM (2012), as well by the recently published SAMHSA guidelines, Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women with Opioid Use Disorder and Their Infants (2018). MAT services should be available for women and their families in all care settings across the ASAM continuum of care: early intervention, outpatient services, intensive outpatient/partial hospitalization, residential/inpatient services, and medically managed intensive inpatient services. For early intervention, outpatient and intensive outpatient services, this may mean development of family goals and inclusion of family members in treatment sessions. For residential treatment, this may mean flexible configurations to include families of all sizes in the residential treatment facility.

For infants, MAT is recommended, in addition to non-pharmacological treatment, when there are symptoms of moderate to severe NAS (SAMHSA, 2018). Research shows that medical intervention to control withdrawal symptoms is required in 27 percent to 91 percent of neonates with NAS (Kocherlakota, 2014). Regardless of setting, in family-centered treatment, the woman and her family are at the center of the treatment.

Physical Health Services/Pediatric Care. Pregnant and parenting women with OUDs and their children often have co-occurring health problems that have not been treated while the woman was under the influence of opioids. In a family-centered framework, physical health services/pediatric care should include primary care; prenatal and postnatal care; emergency/crisis and hospital care; chronic diseases care; and reproductive and sexual health care. Primary care providers should collaborate with specialty providers knowledgeable about MAT utilization during pregnancy and with hospitals regarding delivery policies and MAT practices. Access to family planning services is particularly important for women with OUD. One multi-site, clinic-based study found that 86 percent of pregnancies among women with OUD are unintended versus 45 percent in the general population (Heil et al., 2010).

Mental Health Services. Pregnant and parenting women with OUD are at risk for co-occurring mental health disorders, such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, psychotic disorders and other disorders. Data from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimate that in the past year 8.5 million adults in the United States had both any mental illness and an SUD, which correlates to 3.4 percent of adults (SAMHSA, 2018). An estimated 3.1 million adults aged 18 or older in the United States had co-occurring serious mental illness and an SUD in the past year, corresponding to 1.3 percent of adults. If unrecognized and untreated, psychiatric disorders can interfere with recovery from OUD.

Pregnant and parenting women with OUD are also at risk for mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, which may be the result of sexual assault trauma or domestic violence (SAMHSA, 2018). Family-centered care provides mental health services for the entire family to include a non-judgmental approach to screening, as well as assessment, evaluation, treatment, medications, counseling, cognitive behavioral therapies and other evidence-based treatment. Due to the high percentage of women with OUD and their children experiencing violence and trauma, access to trauma-informed mental health services is key.

Parenting/Child Development. A family-centered framework includes parenting and child development education for the pregnant and parenting women with OUD in order to improve her ability to care for her children. Women with OUD, who may have a history of child abuse often have a need for specialized parenting skills and support. Parenting programs specific for families with SUD such as Celebrating Families, Strengthening Families, and Nurturing Families would be most applicable.

Child Welfare. Many pregnant and parenting women with OUD in treatment are involved with the child welfare system and family courts to determine whether their children may safely remain in their care. Women in treatment may have requirements ordered by the court and monitored by the child welfare agency to maintain their parenting role or to support reunification with children who may have been removed from their care. In a family-centered framework, providers work collaboratively with child welfare and help women meet their requirements to resume parenting responsibilities or to prevent child removal all together.[8]

Supportive Services. Access to safe housing and reliable transportation, with access to schools and child care, are a critical component of treatment for women with OUD and their families. Family-centered treatment provides access to social and community-based services to support women and their families.

Employment. For pregnant and parenting women with OUD, maintaining economic security for themselves and their families is an important component of the recovery process. Often, women with OUD have significant barriers to employment that require specialized employment counseling, job development services or advocacy with employers. A family-centered framework includes access to training and employment services along with child care to enable women to search for jobs and to retain employment.

Criminal Justice. When mothers also are involved in the criminal justice system, linkages and communication with probation and parole staff are critical. Criminal justice requirements may include drug testing, court appearances, and documentation about treatment progress toward goals. Often these communications require access to the community's legal aid services and should include referral to, and coordination with, treatment providers.

A family-centered approach may also include linkages to family drug courts. Family drug courts are designed to be a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach to serve women with SUD and their children who are involved with the child welfare system. Best practice for a family drug court includes bringing in representatives of SUD treatment, child welfare, mental health treatment and social services in order to engage and support the family (Children and Families Futures, 2015).

3.1.3. Embedded Components of Family-Centered Care

Care Coordination Services. Care coordination is an important component of the treatment framework for pregnant and parenting women with OUD that should be embedded throughout programs to support family-centered principles. Care coordination ensures appropriate linkages are made for women and their children and ensures on-going coordination. Care coordination may be provided by professional staff or paraprofessional staff, such as a peer navigator. A peer navigator is an individual with personal experience with SUD recovery and is someone who has had experience "navigating" the SUD treatment service system and can act as a coach and help manage and coordinate care, communicate with providers and provide overall support.

Trauma-Informed Care. A history of abuse or neglect is a risk factor for SUD (Stone et al., 2012). Treatment programs serving pregnant and parenting women serve a high number of women with a history of abuse. One North Carolina residential treatment program reported that at least 80 percent of the women treated come in with childhood or adult abuse (Jones, 2018). Trauma-informed care should also be embedded in a family-centered framework for pregnant and parenting women with OUD. Trauma-informed, or trauma-responsive, care supports a treatment framework that involves understanding, recognizing, and responding to the effects of all types of trauma. Trauma-informed care should emphasize physical and psychological safety for pregnant and parenting women with OUD and their families and should assist women in rebuilding a sense of control and empowerment over their lives and their recovery process.

4. SELECT FINDINGS FROM A STATE PROGRAM SCAN

This section provides key findings from a scan of states supporting programs that offer family-centered MAT for pregnant and parenting women with OUD. We discuss statewide availability of programs, eligibility rules and requirements across states, clinical and community-based services coordination and other themes identified from the program scan.

To narrow the focus of the search, RTI decided to focus on the top 21 states that are heavily impacted by the opioid epidemic with the idea that these states would be more likely to develop state policies providing for the development of family-centered MAT for pregnant and parenting women. RTI developed an algorithm to identify the states with:

-

the highest rate of opioid prescriptions per 100,000 persons;

-

the highest levels of female opioid related death; and

-

the highest incidence of NAS.

The states included in the scan along with opioid prescription data, opioid related deaths and rate of NAS are found in Appendix A.

4.1. Statewide Initiatives Versus Standalone Programs

Most states included in the program scan conducted for this study have standalone specialized SUD programs for PPW with OUD, typically a standalone residential treatment program or intensive outpatient program that services a specific region of the state. However, only one third of the reviewed states have existing statewide initiatives for family-centered treatment for PPW, including access to MAT. Of the 21 states featured in the scan, 11 states (Illinois, Kentucky, Maine, Mississippi, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Texas, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Vermont and Wisconsin) have statewide initiatives that incorporate family-centered treatment either through state amendments, policies, or funding of pilot programs. Six of these 11 states (Kentucky, Maine, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas and Vermont) have family-centered MAT programs specifically for PPW with OUD.

One state, North Carolina, supports a family residential treatment program for women with SUD and their children that is available statewide. CASAWORKS for Families Residential Services consists of 28 programs using evidence-based treatment models located in 13 counties across the state. Family-centered characteristics of the CASAWORKS programs include accommodations for women's children up to age 11, a service array include life skills training, parenting education, child care and transportation, and the ability for women to reside in the program for up to one year. West Virginia is planning to expand their Drug Free Moms and Babies program, an integrated, comprehensive SUD program for PPW from four regional sites to 12 sites across the state. Family-centered aspects of this program include recovery coaches and long-term follow-up for mothers and their babies.

States are using a variety of funding sources to support family-centered SUD services for PPW. Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant funds, Opioid and MAT State Targeted Response (STR) funds, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funding and state funds have been used to support a variety of services to PPW and infants with NAS. A few states have received Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers and State Plan Amendments to expand and enhance MAT and other SUD services to PPW and their families. Of note, some states are beginning to take advantage of the new Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services policy announced in the November 1, 2017, State Medicaid Director's memorandum outlining a more flexible, streamlined approach to accelerate states' ability provide a targeted response to OUD.

A few states are beginning to use 1115 waivers to enhance services to PPW with OUD. For example, in Kentucky, the KY HEALTH (Helping to Engage and Achieve Long Term Health) 1115 Medicaid expansion waiver supports the Kentucky Opioid Response Effort (KORE) which includes services to PPW for 60 days after the pregnancy ends. KORE dedicated state resources for prevention, increase access to MAT, increase recovery support services designed to improve treatment, increase access to naloxone, and enhance statewide coordination and evaluation of health care strategies. Maryland's Health Choice 1115 Demonstration expanded eligibility and services for PPW with SUD that includes an Evidence Based Home Visiting pilot program for high risk pregnant women and children up to two years for 60 days after the pregnancy ends. New Mexico's 1115 Demonstration Waiver for Centennial Care 2.0 piloted the Nurse Family Partnership (NFP) and the Parent as Teachers (PAT) program to benefit pregnant and parenting women with OUD. NFP is a national program designed to reinforce maternal behaviors that encourage positive parent child relationship until the child reaches two. PAT provides parent with child development knowledge and parenting support until the child is five. Finally, Virginia's Innovative, Focused and Scalable Delivery System Transformation 1115 waiver covers cases management services for high risk pregnant women and children up to age two, including pregnant women with SUD. This includes expanded prenatal care services, patient education, nutritional assessment counseling and follow-up, homemaker services and blood glucose meters for 60 days after the pregnancy ends.

In addition to 1115 waivers, a few states have expanded Medicaid eligibility and services covered by Medicaid. In Illinois, the state leveraged the Illinois Opioid Action Plan to increase access to MAT for PPW and outlined Medicaid eligibility under Managed Care Organizations for treatment of OUD including PPW for 60 days after the pregnancy ends. This included expanding Medicaid eligibility and services covered by Medicaid as well as providing comprehensive resources through the Opioid Use Treatment Resource Manual. Illinois leveraged the Illinois' State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis Grant (STR Grant) to fund prevention, treatment, and recovery programs across the state. In Wisconsin, the State Plan under Title XIX of the Social Security Act expanded case management services that includes a face-to-face or telephone contact every 30 days if the child is aged six months or less and contact with the recipient every 60 days if the child is aged 12 months or less. The covered activities include periodic reassessments and time spent on recordkeeping, which includes updating the care plan, documenting patient contacts, preparing and responding to correspondence to the patients contact, and documenting the patient's activities in relation to the care plan.

4.2. Eligibility Rules and Requirements Across States

Eligibility requirements for standalone programs treating pregnant and parenting women with OUD vary across programs. Some requirements, such as a proven record of sobriety prior to entering the program and limitations placed on the age of children who can accompany pregnant and parenting women in residential treatment could potentially create a barrier to family-centered care.

Mechanisms used to fund statewide treatment initiatives are accompanied by program eligibility requirements that dictate the type of services provided or duration of care. Statewide requirements can be both facilitators and barriers to treatment. Some states require that providers report when substance use by pregnant women is confirmed or suspected. In a subset of these states substance use during pregnancy is legally defined as child abuse or can be used as grounds for civil commitment. At the same time, many states require general programs to give priority access to pregnant and parenting women and protect women from discrimination in publicly funded programs. Under the rules of SAMHSA's Substance Abuse Block Grant, every state has to provide priority access to treatment for pregnant women. A review of state policies for selected states is provided in Exhibit 2.

| EXHIBIT 2. State Policies Regarding Reporting and Treatment of PPW with OUD Across Selected States | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Require Reporting of Suspected Drug Use |

Require Providers to Test for Drugs if Use is Suspected |

Drug Use During Pregnancy is Considered Child Abuse |

Drug Use During Pregnancy is Grounds for Civil Commitment |

Priority Access to Treatment Given to Women |

Protections Against Discrimination for Women Seeking Treatment |

Targeted Program and Other Policies for PPW with SUD |

|

| California | X | X | |||||

| Delaware | X | ||||||

| Florida | X | X | X | ||||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Kentucky | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Maine | X | X | |||||

| Maryland | X | ||||||

| Massachusetts | X | ||||||

| Mississippi | X | ||||||

| Montana | X | ||||||

| New Hampshire | X | ||||||

| New Mexico | X | ||||||

| North Carolina | X | ||||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | |||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | ||||

| Texas | X | ||||||

| Utah | X | X | X | ||||

| Vermont | |||||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | ||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | X* | ||

| * Information retrieved from Guttmacher Institute in July 2018, https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/substance-use-during-pregnancy. | |||||||

4.3. Care Coordination

Care coordination is a key component of family-centered MAT for pregnant and parenting women. High-quality family-centered care coordination incorporates clinical care and coordination with non-clinical resources as well as other state agencies and local resources. Care coordination varies widely by state and program but most programs treating pregnant and parenting women with OUD incorporate some level of care coordination.

Treatment programs for pregnant and parenting women offer an array of clinical and non-clinical services to support recovery. For example, New Expectations in Delaware provides MAT, clinical counseling, peer specialists, and recovery coaches. The Moms in Recovery (MIR) Program in New Hampshire offers a range of coordination services such as help accessing housing, transportation, insurance and employment support, in addition to coordinating physical health, mental health and OUD treatment.

Statewide initiatives typically include coordination of clinical and non-clinical services. For example, the Birth to 3 Program in Wisconsin, a State Plan Amendment, provides case management to PPW. A requirement of this initiative is that the case manager identify and schedule at least the initial appointment for all clinical and non-clinical services for participating PPW.

4.4. Statewide Initiatives for Capacity Building

The North Carolina Pregnancy and Opioid Exposure Project is an umbrella under which information, resources and technical assistance are disseminated regarding the subject of pregnancy and opioid exposure. The project is hosted by the University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Social Work and is funded by federal Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant funds. The State of Illinois supported a collaborative effort to develop a resource, the Opioid Use Treatment Resource manual, to create awareness about available treatment resources for pregnant Illinois women who are insured by Medicaid and to illuminate geographical areas with gaps in services. In addition, the Women's Plan and Practitioner's Toolkit was created by the Women's Committee of the Illinois Advisory Council on Alcoholism and Other Drug Dependency for the Illinois Department of Human Services/Division of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse. The toolkit includes trainings and resources to create innovative and best practices programming to ensure appropriate care to women and their families. It also builds collaborative teams between child welfare, public health, substance abuse and mental health community providers and medical professionals to address policy and practice to address the needs of pregnant women with OUD.

4.5. Partnerships

States are engaging in a number of different partnerships to support treatment for pregnant and parenting women with OUD. State agency and university partnerships support multiple educational, funding and data collection initiatives. The Massachusetts Technical Assistance Partnership for Prevention (MassTAPP) supports communities across the state in addressing substance abuse prevention and treatment. Funded by the state and SAMHSA, the partnership offers multiple training and technical assistance opportunities and supports capacity building throughout the state for expansion of SUD services, including services to pregnant and parenting women.

Many states are building upon the federal requirements of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 to strengthen data capture efforts around identification and treatment of infants with NAS and their mothers and engaging in collaborative statewide measurement and evaluation efforts. Many of these have developed task forces, committees, projects, and toolkits to conduct data collection activities for statewide measurement and evaluation efforts. Exhibit 3 demonstrates states with task forces, committees, projects and toolkits for these purposes.

| EXHIBIT 3. Statewide Partnerships for PPW with OUD | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | Initiative | Objective of Initiative |

| Illinois | NAS Advisory Committee | NAS Advisory Committee assists the Department of Public Health with developing appropriate and uniform definitions, identification processes, hospital training protocols, and reporting options with respect to NAS, as well as to make recommendations on evidence-based guidelines and programs to improve pregnancy outcomes. |

| Mississippi | Governor's Opioid and Heroin Study Task Force | The Governor's Opioid and Heroin Study Task Force provides recommendations of how to best fight opioid and heroin abuse and how to prevent it in the future. Pregnant and parenting women were named as a target group for these efforts and the expansion of MAT. |

| New Hampshire | Perinatal Substance Exposure Task Force; Data Collection and Evaluation Task Force | Perinatal Substance Exposure Task Force advises the Commission on ways to lessen barriers pregnant women face when seeking quality health care, aligning state policy and activities with best medical practices for pregnant and newly parenting women and their children, and increasing public awareness about the dangers of exposure to prescription and illicit drugs, alcohol and other substances during pregnancy. Data Collection and Evaluation Task Force is working to identify the most appropriate tools for evaluating New Hampshire's alcohol and drug abuse programs. The task force is planning to publish data through an online data dashboard. |

| Rhode Island | NAS Task Force | NAS Task Force developed guidelines for maternal and neonatal management of substance exposure, neonatal withdrawal and other drug effects. The Task Force has developed a 2-year plan with work groups that focuses on: (1) peer supports for pregnant and parenting recoverees; (2) prenatal referral and linkage to care (substance use treatment, prenatal care, family support programs); and (3) hospital protocols for supporting substance exposed pregnancies at delivery. |

In addition, many states participate in the national initiative which is a quality improvement initiative for addressing maternal mortality and severe morbidity in birth centers funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) is a maternal safety bundle program that developed best practices for maternity care and is endorsed by national multidisciplinary program. These maternal safety bundles include action measures for: (1) Obstetrical Hemorrhage; (2) Severe Hypertension/Preeclampsia; (3) Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism; (4) Reduction of Low Risk Primary Cesarean Births/Support for Intended Vaginal Birth; and (5) Reduction of Peripartum Racial Disparities Postpartum care access and standards. States participating in AIM featured in the scan include New Mexico, Texas, Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, Ohio, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine.

5. FINDINGS FROM INTERVIEWS

5.1. Overview

During our key information interviews, we spoke with state officials in four states (New Hampshire, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas) and with provider organizations in three of these states (New Hampshire, Ohio, and Pennsylvania). Collectively, these interviews allowed us to explore the components of family-centered treatment programs across the country, the extent to which they are available in these states, and the ways in which states are approaching program eligibility, funding, community linkages and partnerships, and common barriers to access.

Exhibit 4 summarizes key dimensions of MAT treatment programs in these four states. In the following case studies, we provide a more detailed look at the ways in which states have structured and funded their programs.

| EXHIBIT 4. Key Dimension of MAT Treatment Programs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Hampshire | Ohio | Pennsylvania | Texas | |

| Program | MIR | MOMS | COEs | Mommies |

| Eligibility | No state requirements for eligibility | State requires that woman must be 18 years of age or older and diagnosed with a SUD | No state requirements for eligibility | No state requirements for eligibility |

| Funding | STR funds and Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment waiver which funds intensive outpatient and case management services | MOMs initially funded with $4.2 million from the Governor; presently financed with STR funds | STR funds and earmarked state dollars for COEs | STR funds and general revenue funds |

| Family-centered Services | MAT, SUD treatment and counseling, recovery support services, child care, parenting classes, and case management | MAT, prenatal and postnatal care, SUD treatment and counseling, child care, and recovery support services | MAT, prenatal and postnatal care, SUD treatment and counseling, child care, family planning services, and parenting classes | MAT, prenatal and postnatal care, SUD treatment and counseling, child care, parenting classes, life skills education, case management |

| Community Linkages | Varies by site but generally linkages to child care, income support, housing, job training, and transportation. | Varies by site but generally linkages to transportation, child care, and housing. | Varies by site but COE's operate under a "hub and spoke" model where provider connects women to a range of services including housing, job training, child care, and transportation. | Case management is offered to facilitate access to medical care and connect pregnant women with needed resources in the community. |

| Partnerships | State is partnering with the Department of Children Youth and Families to assist children whose parents are struggling with SUD. The state has also created a Perinatal Substance Exposure Task to recommend strategies for aiding pregnant and parenting women with SUDs. | Statewide steering committee comprised of staff from various state agencies, MOMS providers, the Ohio College of Medicine, and managed care organizations oversees the MOMS initiative. State is also training MOMs providers to build relationships with local child welfare agencies. | The state is partnering with the March of Dimes to develop perinatal collaborative focused on pregnant women with OUD and NAS. | The Mommies program involves collaboration between the Methadone Treatment Center, Texas DSHS, and University Health System. The state is partnering with the state child welfare agency to develop a Mommies Education program. |

5.2. New Hampshire Case Study

5.2.1. Overview of State Initiatives

Dartmouth-Hitchcock's MIR program is a leader in the fight against OUD among pregnant women in New Hampshire. The MIR program was created in 2013 after a group of hospital obstetricians and gynecologists (OB-GYNs) observed an increase in the number of pregnant mothers with SUD missing their prenatal visits at the Dartmouth clinic. The program now offers an intensive outpatient treatment program, which includes MAT and a range of other services, to pregnant women with histories of opioid abuse. Funded through a 21st Century Cures grant of $2.7 million, MIR is currently being expanded to seven additional maternity care practices throughout the state.

The Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services has also created a best practice guide for delivering community-based MAT services for OUDs. Intended to increase access to MAT services statewide, the guide outlines requirements for implementing a MAT program in a primary care clinic, behavioral health setting, or a free-standing MAT or methadone clinic. The guide does not specifically discuss considerations pertaining to pregnant women.[9]

5.2.2. Family-Centered Services and Care Coordination

MIR sites offer MAT, group and individual SUD treatment and counseling, recovery coaching, parenting classes, and case management services. Child care is made available to all women during their visits. Case managers perform a psychosocial assessment and use a social determinants of health screener to help link women to an array of community services including income support, housing, job training, and transportation. All OB-GYNs receive training in trauma-informed care.

The Dartmouth-Hitchcock location also has a midwife located on site as well as primary care, obstetrics, and mental health clinicians. A pediatrician visits the clinic twice a month. Although other MIR sites are encouraged to replicate the Dartmouth-Hitchcock model, the state allows flexibility in implementation to accommodate variations in providers and regions. Family members can attend treatment meetings when they are supportive. Dartmouth-Hitchcock originally offered individual sessions for fathers at one time, but they discontinued this service because many relationships were abusive. Now, they refer male partners to the general SUD treatment program at the hospital.

The Dartmouth-Hitchcock MIR program has also evolved to provide on-going support to women for many months and sometimes years after delivery. This extension of services was aided in part by New Hampshire's decision to expand Medicaid in 2014 which allows more pregnant women to retain their Medicaid coverage after delivery.

5.2.3. Partnerships

Modelled after Kentucky's Sobriety Treatment and Recovery Team program, New Hampshire is partnering with the Department of Children, Youth and Families to help children involved with the child welfare system whose parents are struggling with SUD. Titled Strengths to Succeed, the program would provide fast-track access to SUD treatment services for parents as well as counseling and services for the children. Child welfare workers would partner with family mentors who have achieved sobriety and have experience with the child welfare system to assist families.

New Hampshire has also created a Perinatal Substance Exposure Task Force, whose mission is to educate and inform the Governor's Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse, Prevention, Treatment and Recovery on pertinent issues related to pregnant and parenting women with SUDs. The Task Force, which was created in 2015, is currently working in collaboration with the Division of Public Health Services and the Division of Children, Youth and Families on developing a Safe Plan of Care for women impacted by substance use. The Task Force is planning a summit scheduled for January 2019 to discuss optimizing care for mothers and babies affected by SUD.

5.3. Ohio Case Study

5.3.1. Overview of State Initiatives

In response, the state created the Maternal Opiate Medical Supports (MOMS) initiative which officially launched as a pilot in mid-2014. The MOMS initiative provides treatment to pregnant mothers with opiate issues during and after pregnancy through a Maternal Care Home (MCH) model of care. MOMS began as a partnership between the Ohio Governor's Office of Health Transformation, the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, and the state's Medicaid agency. Currently there are nine provider sites implementing the MOMS model and the state expects to add three more sites by the end of 2018. All 12 sites are public behavioral health providers or federally licensed opioid treatment program (OTP) providers.

|

As compared to a Medicaid comparison group:

Rick Massatti, Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction, Improving Maternal-Infant Outcomes. Presentation for Department of Health and Human Services (April 2018). |

The state's Perinatal Quality Collaborative, a Medicaid-funded consortium founded in 2007, launched MOMS+ in 2018 to train individual obstetricians and maternity care providers on how to recognize and treat OUD in pregnant women. The goal of MOMS+ is to reach those pregnant women who do not have access to a local behavioral health provider. Through a mentor-partner model, the program aims to expand the capacity of maternity care providers to treat pregnant women by providing or arranging for MAT, behavioral health counseling, and other social services. Full implementation of MOMS+ is expected to be completed by the end of 2018. The Collaborative has also developed a NAS protocol to assist states and providers reduce hospital length of stay among newborns with NAS.

Initially funded via a $4.2 million grant from the state, Ohio is applying some of its Phase 1 and Phase 2 grant funding from the Opioid STR Grants initiative to sustain the program. The state intends to continue financing its MOMS initiative in future years with Medicaid funding.

5.3.2. Family-Centered Services and Care Coordination

Each MOMS' provider varies slightly in types of services they offer but they are all required to directly offer or provide access to the following services: MAT, prenatal and postnatal care, SUD treatment and counseling, housing, and recovery support services.[10] The model emphasizes team-based care and care management for moms and babies. Some offer inpatient residential treatment whereas others provide outpatient services only. Targeted programming for dads is not a key element of MOMS at present, although the state intends to emphasize this with its MOMS expansion. MOMS providers are also strongly encouraged to co-locate clinical providers such as obstetricians and pediatricians on-site throughout the week.

First Step Home is an addiction recovery center for women in Greater Cincinnati, funded through the MOMs program, which allows women to live with their children up to age 12, as they recover from their SUD. The Center provides individual and family counseling, mental health services, MAT, residential treatment, transitional housing, parenting classes, vocational counseling, and continued outpatient treatment, case management for the newborn and coordination with pediatric and family health care. The program has found that housing is critical to ensuring stability; women have a very hard time finding safe/affordable housing in the community after residential treatment so First Step is increasing its housing options on site. Apart from the on-campus housing and residential program, First Step Home also operates The Terry Schoenling Home for Mothers and Infants, an eight-bedroom house that helps women with OUD bond with their newborns from two weeks before delivery to 30 days postpartum.

MOMS sites are required to create community linkages with non-clinical entities to help women transition back into daily life after giving birth. This includes linkages with child care providers, transportation entities, housing support organizations, employment resources, and others. The state encourages new MOMS sites to complete a "community readiness" process, which involves holding meetings with stakeholders in the community to educate them about the program, solicit their support, and build relationships.

To further incentivize care coordination and care integration for treatment of behavioral health conditions and SUD, Ohio is designing a qualified behavioral health entities (QBHE) initiative in its Medicaid program, scheduled to launch in 2019. Under the QBHE program, qualified providers may be eligible to receive an additional $200 per-member, per-month to better coordinate SUD services and deliver wrap around care (i.e., education, social services, etc.) to pregnant women and their families. MOMS providers are eligible to participate.[11]

5.3.3. Partnerships

A statewide steering committee oversees the MOMS initiative. The committee is comprised of representatives from the state Office of Health Transformation, the Department of Mental Health and Addiction, and the state Medicaid agency, as well as participating MOMS providers, evaluators from the Ohio College of Medicine, and representatives from managed care organizations.

To promote collaboration between MOMS providers and state agencies, the steering committee partnered with the state Department of Job and Family Services to help MOMS sites build relationships with their local child welfare agency. Child welfare agencies help MOMS providers understand state reporting requirements and legal mandates and MOMS providers educate local child welfare agencies about MAT and their services for pregnant and parenting women.[12] As required by the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 2015, child welfare authorities are required to complete a plan of safe care for each infant born to a woman with a SUD. As a result of these partnerships, pregnant women are working jointly with their MOMS providers and child welfare caseworkers to develop these plans of care. Child welfare agencies can also assist in providing resources to support a women's recovery pre-delivery and post-delivery.

As mentioned above, the state Medicaid agency also created the Ohio Perinatal Quality Collaborative -- a statewide consortium consisting of perinatal clinicians, hospitals, policymakers and governmental entities which created the MOMS+ initiative in 2018.

5.4. Pennsylvania Case Study

5.4.1. Overview of State Initiatives

Centers of Excellence (COEs) began in Pennsylvania in 2016 in response to the opioid crisis. COEs act as health homes for Medicaid-insured individuals with OUD, and they provide a high level of care coordination and integration of behavioral health and primary care. Pregnant women with OUD have been identified as a priority population in this initiative. COEs operate under a "hub and spoke" model, in which the designated center serves as a health home and connects individuals to needed care throughout the community, through partnership with hospitals, providers, correctional facilities, law enforcement, courts, emergency medical services, and more. There are currently 45 COEs across the state, 25 of which are behavioral health entities and 20 of which are physical health entities. These COEs are located in both urban and rural areas.

|

Funding

|

One COE, Magee-Women's Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), has operated a Pregnancy Recovery Center for pregnant women with OUD since 2014. The Center provides office-based buprenorphine treatment, behavioral health counseling, social services, and prenatal care.

The state is also funding large health systems to be care coordination "super hubs," described by one state official as "COEs on steroids." There are currently nine super hubs across the state that work with communities to provide intensive care coordination through a team of care management staff to ensure that everyone with OUD -- including pregnant women -- is connected to the appropriate resources and care. Super hubs will also provide training to other COEs. Pennsylvania has also contractual requirements with their managed care plans to develop health homes for pregnant women within high-volume OB-GYN health systems. These health homes are expected to have contracts in place to support and supplement care management activities for pregnant women.

Pennsylvania expanded Medicaid eligibility under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which led to approximately 710,000 adults who were newly eligible for Medicaid coverage. The state has a behavioral health "carve out," and both physical and behavioral health and overseen by managed care organizations.

5.4.2. Family-Centered Services and Care Coordination

COEs, super hubs, and managed care health homes are all encouraged to look beyond medical aspects of treatment and care management and focus on social determinants of health like housing, domestic violence, food insecurity, and reestablishing family relationships. Additionally, they are encouraged to take a trauma-informed and trauma-responsive approach to treatment that acknowledges and addresses the underlying trauma that exists for many individuals with OUD. The Pregnancy Recovery Center at Magee-Women's Hospital -- which characterizes itself at women-centered, rather than family-centered -- provides child care, prenatal and postpartum care, pregnancy-specific dosing, housing and transportation assistance, breastfeeding education and support, family planning counseling, sexually transmitted infection screening, parenting skills training, and individual and group counseling.

Some COEs take a broad approach to treatment, with increasing engagement of family members such as the father, grandparents, and expended family. One state official noted that Medicaid expansion has allowed many more males to be covered in Pennsylvania, and COEs want to engage these individuals in a family-centered treatment model.

Care coordination is integral to the COE "hub and spoke" model of care. The care management team oversees comprehensive, wraparound care for individuals in their care and makes referrals to community partners when for needs that cannot be met internally (e.g., housing, job training, and -- for that that do not provide MAT themselves -- community-based MAT providers). Some women seek care at a COE that is far from their home, due to a lack of intensive resources closer to them, and the COE can also help them find counseling in their community.

5.4.3. Partnerships

Pennsylvania reports robust partnerships throughout the state with few barriers to collaboration. Explained one state official, "People are very receptive [to collaboration]. This is a crisis, with 13-14 Pennsylvanians dying every day." The state is currently working with the March of Dimes and another non-profit organization in the state to develop a statewide and regional perinatal collaborative focused on both pregnant women with OUD and NAS babies. The collaborative -- which is still in development and aims to operationalize in the last quarter of 2018 -- will bring together partners including the Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs, Department of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, and various provider stakeholders. Another partnership is supported through recent legislation which mandated the creation of a statewide maternal mortality review, based off the Philadelphia review process, which will involve multiple state agencies and be overseen by the Department of Health. Also, non-state partnerships in the state include faith-based collaboratives that bring together community partners to support individuals with OUD, though these are not specific to pregnant women.

5.5. Texas Case Study

5.5.1. Overview of State Initiatives

In 2007, Project Cariño launched in San Antonio through a $2.5 million PPW grant to the Center for Health Care Services (CHCS), the local mental health authority. At the time, one-third of all cases of NAS in Texas were concentrated in Bexar County (where San Antonio is located). The program provided comprehensive substance use and mental health services (offered by CHCS) with prenatal and neonatal care through a local hospital system. The program sought to improve birth outcomes for babies born to mothers with SUD, provide prenatal education and care, and shift provider attitudes and behaviors around this population of pregnant women. Together, these efforts contributed towards a reduction in length of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) stays for NAS babies by 33 percent.[13]

|

Since the Mommies Program began in San Antonio, Texas, average NICU length of stay for NAS babies has decreased by 33%. |

Inspired by these positive results, the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) expanded the program to other hospitals statewide in 2013 and changed the named to the Mommies Program. This name was described by state officials as a "stigma reducing term" that indicated to providers that a pregnant woman with SUD was "just one of the other mommies." The program provides intensive outpatient treatment -- including MAT -- for pregnant and parenting women with SUD.

In addition to the Mommies Program, Texas has a continuum of treatment for SUD services that ranges from prevention to intervention to clinical. Texas is participating in the national HRSA AIM program and plans to pilot the opioid bundle in nine hospitals, seven of which are original Mommies program. An implementation plan is currently in development.

Texas did not expand Medicaid eligibility under the ACA. Medicaid covers MAT, but pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage is typically terminated six weeks postpartum. Some general revenue state funding is available through NAS-opioid treatment service providers to provide women with MAT services after they have exhausted their pregnancy-related Medicaid through 18 months postpartum, with the goal of avoiding treatment disruption.

5.5.2. Family-Centered Services and Care Coordination

Mommies programs coordinate wraparound services for pregnant and parenting women with any type of SUD, and provide MAT during pregnancy, a postpartum recovery program, and 13-weeks of parenting and life skills education. An individualized treatment plan is developed for all participants and may include substance abuse counseling, crisis intervention, case management, individual therapy, family therapy, and group therapy. All women in the program with OUD enter into MAT. Programs employ evidence-based models including the Trauma, Recovery, and Empowerment Model, which focuses on recovery from trauma and abuse through gender-specific treatment, and Seeking Safety, which addresses trauma and addiction. A patient navigator or recovery coach (both terms are used) -- a degreed professional with lived SUD experience -- is accessible 24 hours a day via cell phone and acts as a coach, role model, and advocate as participants interface with other agencies. They also assist with coordinating educational sessions. Although Mommies is women-specific, Texas also has a Parenting Awareness and Drug Risk Education program for expectant and parenting fathers.

|

Funding The statewide Mommies Program is funded primarily through general revenue in the annual budget. Most recently, it was allocated $11.2 million over a two-year period. Other funding for SUD treatment in the state comes from federal grant funding (21st Century Cures Act, STR to the Opioid Crisis Grants, and SOR Grants), block grant funding, state general revenue dollars, and Medicaid reimbursement for certain clinical services. Prevention and intervention services are typically non-billable and funded through program contracts. |

Mommies programs are contractually obligated to provide therapeutic and clinical services, but the nature of service provision varies. Some sites provide all services on-site, including clinical services like vision and dental, while others partner with providers in the community.

5.5.3. Partnerships

The Mommies program involves public-private collaboration between Mommies Program is a collaboration between the Methadone Treatment Center, Texas DSHS, and University Health System. The program also partners with a variety of service-providing agencies that working with participating women, such as the Adult Probation Department.

Additionally, the Texas DSHS has partnered with the state child welfare agency to develop a Mommies Education program. This program began due to child welfare desire to be involved with pregnant women with OUD before the child is born and provide a complete treatment plan around prenatal care, education, and other aspects related to the care of the child. Mommies Education provides prenatal education targeted to this population of pregnant women and covers topics that may not be discussed in traditional parenting classes, such as pain management while on methadone and NICU visitation.

6. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES RELATED TO TREATMENT

6.1. Insurance Coverage

6.1.1. Challenges

Respondents from the interviewed states discussed challenges faced by women insured by Medicaid and by private plans. One state official noted substantial variation in covered treatment services among private plans in the state; for example, one plan will reimburse members for residential treatment services but not higher-level specialty services for pregnant and parenting women. This lack of consistency among plans presents challenges for this group of women.

Most of the barriers discussed were on the Medicaid side, however. In states that did not expand Medicaid eligibility under the ACA, many low-income women are uninsured until they become pregnant, obtain pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage during pregnancy and delivery, and then lose this coverage several weeks postpartum. At this point, as one state official explained, "Babies have coverage, but where does the mother go for treatment?" Women may initiate MAT upon gaining temporary Medicaid coverage and then discontinue when they lose coverage postpartum. This abrupt discontinuation of treatment during a vulnerable period of time can prove dangerous and lead to relapse. In non-expansion states, some women are eligible for Medicaid coverage due to their status as a parent to dependent children. Federal officials discussed that in these states, a woman can lose coverage if she enters residential treatment without her children, as she may be required to give up her caregiver status.

Even women who are insured by Medicaid may face barriers to accessing treatment, due to limited scope of coverage. Methadone is not covered under every state program, and one provider explained that in recent years, their state government limited their ability to bill Medicaid for case management in certain outpatient treatment settings. Other non-reimbursable services mentioned across states include professionals such as peer recovery coaches, care managers, lactation consultants, and child life specialists.[14]

In addition, some providers do not accept any insurance. One researcher discussed a recent survey of treatment providers (specifically, opioid agonist providers, OTPs, and outpatient buprenorphine providers) in four states in Appalachia, which found that just over half of these providers accepted any form of insurance and some were unwilling to accept pregnant patients, even when they were accepting new patients more generally.

6.1.2. Opportunities

Interviews with stakeholders in states that expanded Medicaid eligibility highlighted the key role that expansion can play in increasing access to family-centered treatment. In these states, nearly all low-income women are eligible for Medicaid coverage, and -- unlike in non-expansion states -- this coverage does not end in the immediate postpartum period. Low-income men also have substantially more pathways to Medicaid coverage in these states, which presents an opportunity to engaging partners and co-parents in treatment.

Some states have also utilized Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers to expand access to treatment for Medicaid beneficiaries. Kentucky, Maryland, and New Mexico were identified as such states; for example, Maryland implemented an 1115 Demonstration to expand eligibility and services for PPW with SUD.

Additionally, some respondents indicated a preference towards the adoption of more non-fee-for-service payment policies that support incentivizing providers to work in systems such as Accountable Care Organizations or Accountable Health Communities, which allow providers greater flexibility in how they organize and deliver treatment.

6.2. Funding Constraints

6.2.1. Challenges

Insurance coverage is a critical piece of the funding landscape for family-centered OUD treatment, and Medicaid expansion provides a significant and effective opportunity to increase access to this coverage. However, as noted previously, there are a number of non-clinical services -- ranging from care coordination to child care -- that are considered key to family-centered treatment but are not typically reimbursable under Medicaid. Most respondents -- researchers, providers, and government officials -- named funding as a key barrier to expanding access to family-centered MAT programs. Explained one federal official, "I think it's a financing issue more than a desire to not [provide this care]." Funding can prove challenging in a variety of ways. Some respondents, particularly providers, noted that insufficient funding overall has required them to reduce their length of inpatient stay; one organization has reduced their length of stay by 25 percent based on a lack of increase in block grant funding, rather than on best practices or evidence. This provider explained that reduced length of stay is problematic because longer time in treatment is associated with better outcomes for women and their children. These reductions started over the last 2-3 years as the cost of business increased and block grant dollars remained stable. Insufficient funding has also presented challenges for staff recruitment, as programs have a cap on what they can pay employees.

Finally, while many respondents acknowledged the surge of funding currently available to address the opioid crisis, there were concerns about sustainability and flexibility of this funding. One provider explained that "programs and providers are scared to death" because they do not see a plan for sustained funds after 2-3 years, leading to reluctance to expand beds and services; others felt that these feats were not merited and that funding did allow for sustainable investments in treatment programs. Some stakeholders also cited challenges around funding specific to opioid use, because this targeted funding does not allow them the flexibility to treat other SUDs more generally. Two states mentioned methamphetamine use as a problem as severe -- or more severe -- as opioid use in their state, but without the same level of targeted funding.

6.2.2. Opportunities

The states interviewed and included in the program scan cited a wide-range of funding sources used to implement, sustain, and expand access to OUD treatment models, indicative of the profusion of federal funding that has been made available in response to the opioid crises. State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis Grants (Opioid STR) individual grant awards have been utilized by many states, including Delaware, Florida, Kentucky, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, New Hampshire, Texas, Utah, and Wisconsin. The Residential Treatment for Pregnant and Postpartum Women grant program was another commonly used sources of funding for states in this review.

Other sources of funding include State Opioid Response (SOR) grant funding, block grants, state funds, CDC funding, and additional flexibilities in Medicaid funding through Section 1115 Demonstration waivers or State Plan Amendments.

6.3. Workforce Capacity Shortages

6.3.1. Challenges

Respondents from all states mentioned experiencing shortages across several types of addiction professionals -- clinical social workers, licensed alcohol and drug counselors, and psychiatrists. Finding enough addiction professionals was identified as particularly problematic in rural areas throughout Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire. Shortages were attributed to insufficient training in addiction medicine for clinical and non-clinical professionals (e.g., child life specialist, peer providers, care coordinators) as well as a limited pool of applicants. Obstetricians, pediatricians, and family medicine doctors would all benefit from additional education around treating pregnant women and other adults with SUDs, noted one stakeholder. Respondents also noted that many addiction providers cannot afford to pay health care professionals high enough salaries to attract them for permanent positions. Often times they will take a position with the provider for one year and then move on to higher paying positions.

6.3.2. Opportunities

To address workforce challenges, states identified a few solutions. For example, Ohio is using funds from STR grants (authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act) to increase the number of waivered physicians across the state that can deliver MAT. The Ohio Medicaid Department is also working with managed care organizations to develop criteria for "gold carding" physicians who may need to treat patients with OUD. Physicians who receive a "gold card" would be exempt from meeting plans' prior authorization requirements to deliver MAT. To aid in recruitment and retention efforts, Ohio has also created loan forgiveness programs for health care professionals in previous years.

In New Hampshire, state officials have created a workforce development task force to identify strategies for recruiting and training qualified professionals to treat individuals with a SUD.

6.4. Limited Access to Safe and Affordable Housing

6.4.1. Challenges