Executive Summary

Changes to the welfare system brought about by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), and state and local welfare reform efforts, carry serious implications for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) recipients with disabilities and barriers to employment. Specifically, work participation and time limit requirements are two key provisions of the federal welfare law which provide a new sense of urgency encouraging states to develop strategies to assist clients with their transitions from welfare to work. As a first step in this process, TANF agencies are considering strategies to identify the barriers that are inhibiting or prohibiting this transition. PRWORA offers unprecedented flexibility to develop such strategies and design programs and services to assist with the transition from welfare to work.

As caseloads have declined, there is general agreement among TANF agencies that larger proportions of remaining clients are hard-to-serve. Often this means clients are believed to have substance abuse or mental health problems or learning disabilities, or to be in domestic violence situations referred to collectively in this paper as unobserved barriers to employment. Given the employment focus and time-limited nature of TANF, there is increased interest in screening and assessment approaches that can be used to identify these barriers to employment.

In response to this increased interest, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services asked The Urban Institute to explore the issues and challenges related to screening and assessment within the TANF context. This paper represents the earliest work under this effort. It identifies ten of the important questions that should be considered by TANF agencies and their partners as they develop approaches to screening and assessing for barriers to employment. By posing these questions, we hope to further the thinking about options for developing approaches to screening and assessment. However, answers to these questions must be developed by TANF agencies and their partners in order to best meet state and local needs and fit within state and local policy guidelines.

This paper is merely a first step in considering some of the many challenges associated with identifying unobserved barriers to employment. In the second phase of this study, we will conduct case studies to further explore how these issues are addressed in a select number of localities. The report based on the case studies will focus specifically on how those localities have answered the questions posed in this report. Regional meetings intended to facilitate discussion among states and localities facing these challenges will also be convened.

Definitions and Context (questions 1-3)

Before moving to the questions of how, when, and by whom TANF clients can be screened or assessed, there are important questions that must be asked that set screening/assessment in its appropriate context. This context is particularly important for TANF agencies just beginning to consider the challenges associated with identifying unobserved barriers to employment, and for partner agencies who may not be familiar with the details of TANF policy. There are a wide range of barriers faced by TANF clients that generally fall under the heading of hard-to-serve. Examining issues related to identifying barriers to employment is complicated by the lack of common terminology. TANF agencies and their partners should take care to ensure they are using terms in the same way to lessen this complication, and in this spirit, Question One notes how terms are used for the purpose of this paper.

Many TANF agencies are already tackling the challenges associated with identifying barriers to employment and need no convincing of the importance of this issue. However, some staff or partner agencies may be less familiar with the objectives of TANF or prevalence of barriers such as substance abuse and mental health problems, domestic violence situations, and learning disabilities. Question Two provides an overview of incentives to screen or assess clients within TANF as well as a review of prevalence estimates for these barriers. Question Three builds on this discussion, outlining key aspects of TANF policy that provide TANF agencies flexibility in how they meet the needs of TANF clients, while also pointing out the requirements that TANF agencies and their partners must consider when developing screening, assessment, and service approaches.

Approaches to SCREENING/ASSESSMENT - How, When, and by Whom? (questions 4-7)

Approaches to screening and assessment are largely defined by how the case management process contributes to identification of barriers, the use of screening or assessment instruments, the timing of identification efforts, and the staffing arrangements used to carry out screening and assessment. Questions Four through Seven address these approaches.

How can the case management process aid in identifying unobserved barriers to employment?

Case management is an ongoing, multi-faceted process of staff interacting with clients, determining needs, establishing goals, addressing barriers, and monitoring compliance with program requirements. Within the case management context, staff may rely on self-disclosure of a barrier or the observation of behaviors that might be indicative of barriers (red flags) for example, bruises or a client who smells of alcohol as methods of identifying barriers to employment. Although inexpensive to implement, and likely already occurring at some level in most TANF agencies, these approaches may be imperfect if they are the only identification strategies undertaken.

The effectiveness of self-disclosure and behavioral indicators as methods of identifying barriers depends heavily on staff's abilities to make clients comfortable disclosing or eliciting disclosure, as well as staff's understandings of different barriers and the behaviors that are indicative of those barriers. In some locations, these less formal methods of identifying barriers are combined with the administration of screening or assessment tools. However, little is known among the TANF community about the tools that are available and their appropriateness for this population.

Are there tools that can be used to identify barriers to employment?

There are several state- and professionally-developed tools being used by TANF agencies (or recommended for use) to identify substance abuse and mental health problems, learning disabilities and domestic violence situations. Tools vary widely with some screening for multiple barriers while also collecting general background information, and others screening for a single barrier. Tools also vary considerably in length, complexity, and cost.

Experts caution that TANF agencies should be careful when selecting or developing tools to ensure that the instrument is methodologically sound. For example, there are a number of tools that have been developed to screen for substance abuse problems, but we were unable to identify such a tool that was designed specifically for use with TANF clients. In contrast, there are two learning disability screening tools that were designed specifically for use with TANF recipients.

When selecting or developing tools, TANF agencies may consider seeking guidance from partner agencies or community-based organizations with experience identifying or addressing a particular barrier. When selecting tools, TANF agencies must not only consider methodological aspects of the instrument but also the cost of the tool and the staff skills necessary to implement the tool and utilize information obtained.

When should screening or assessment occur?

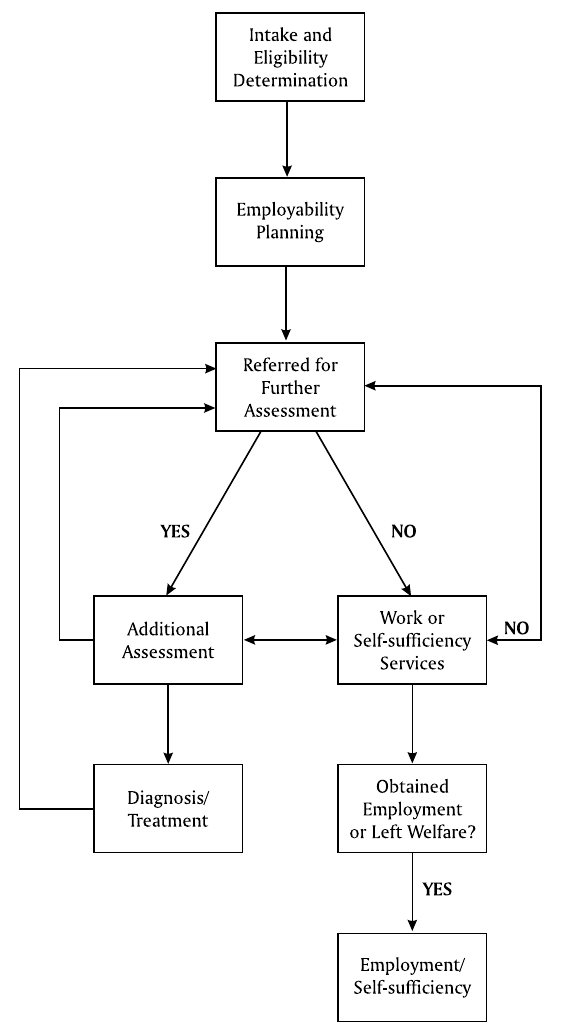

TANF agency administrators interviewed generally considered efforts to identify barriers to employment to be an on-going, dynamic process, noting that there is no singular point in the TANF process when they believe screening or assessment should be carried out. Although the TANF client flow offers a number of opportunities to screen or assess for barriers, staff with whom we spoke noted that they utilize many of these opportunities to further their efforts to identify barriers. For example, TANF program orientations may offer an early opportunity to screen a client for barriers to employment. However, this early screening is often used to determine if a client is eligible for an exemption from participation requirements. The employability planning process offers additional opportunities to uncover barriers and is a common point where formal screening or assessment tools are utilized. As clients participate in work and self-sufficiency activities, re-planning sessions offer further chances to explore the reasons a client has not successfully made the transition from welfare to work.

In some locations, clients are referred to partner agencies for additional services. In some cases, the service received is additional assessment by a subject matter expert or trained clinician. In other situations, clients are referred for work-related services but may receive additional assessment as a part of this process. Finally, some TANF agencies use opportunities presented by non-compliance or lack of success in activities to conduct further assessment. Each of these points in the client flow offer opportunities to further explore barriers to employment. However, there is little information indicating if screening or assessing at any particular point in time yields more accurate information.

Although time limits and work participation requirements provide incentives to conduct screening or assessment early in a clients experience, TANF agencies repeatedly note that they are only concerned with a barrier in so far as it prohibits the client from obtaining or retaining employment. Therefore, even screening or assessment efforts that are conducted up front are conducted within the context of determining services to assist the client with her quest for employment, not based in the belief that the existence of such a challenge necessarily presents a barrier to employment. In some states with a strict work first approach, there is little formal screening or assessment conducted early on and, instead, the labor market is used as the up-front screen to determine job readiness or the existence of a barrier to work.

Who should conduct screening and assessment?

TANF agency officials and subject matter experts generally agree that the most appropriate role for TANF agency staff is to screen clients for barriers to employment and facilitate referrals to organizations with expertise diagnosing and addressing barriers. This belief is based in the fact that many TANF caseworkers are former eligibility or income maintenance workers with little experience with case management and barrier identification. To the extent that this is the case, states may need to consider training existing staff on barriers, screening, or assessment, hiring new staff to conduct screening/ assessment, or creating partnerships with other agencies to assist with screening or assessment efforts.

TANF agencies generally have many partners in the service delivery process. However, for the purpose of identifying and addressing unobserved barriers to employment, TANF agencies may need to develop new relationships or change the nature of existing partnerships. Although resources in communities will obviously vary, other government agencies and communitybased organizations may possess valuable experience identifying and addressing barriers to employment and therefore may be potential partners. Partnerships for the purpose of identifying and addressing barriers to employment faced by TANF clients bring with them many challenges, including understanding respective program philosophies and requirements. For example, partner agencies may not understand the work incentives and work participation rates that exist in PRWORA. In some cases, TANF agencies and their partners may need to consider adaptations in their policies or strategies order to accommodate TANF program requirements such as adapting services to meet shorter time frames or focus more heavily on work-related activities.

Additional Issues (questions 8-10)

Pervading the questions of how, when, and by whom screening and assessment should be conducted are questions relating to staff training and privacy and confidentiality. Although these are two important additional questions, these are merely some of the many questions TANF agencies and their partners must answer.

What training issues are related to screening and assessment?

Regardless of decisions related to the use of tools or informal identification methods, the timing of identification efforts, staffing arrangements and partnerships, it is likely that some training will be necessary. Training may need to be conducted on a wide range of topics including: general awareness of the characteristics of particular barriers, the details of how to administer specific assessment tools, how to determine appropriate services to address barriers once identified, and how to facilitate referrals to partner agencies. Training may also need to be conducted on broader issues of TANF and other program policies as they affect allowable services and the timing of different activities.

Additional training considerations include who to train (including the importance of cross training of partners) and the costs of training (including materials, trainers, and staff time required to attend training). However, there are costs associated with not conducting, or not training, the appropriate staff. Such costs may include inconsistent implementation of screening and assessment approaches, inconsistent information provided to clients by program staff unfamiliar with the program rules or requirements of partner agencies, and unsuccessful program initiatives.

What issues related to privacy and confidentiality should be considered?

Fundamental to the issues of obtaining information about barriers to employment faced by TANF clients and sharing this information with partner agencies in efforts to remove or mitigate such barriers are questions related to privacy and confidentiality. These issues are affected by a variety of laws, perceptions, and individual fears too complex to discuss fully in this report. However, the potential negative consequences of not seriously confronting the importance of these provisions makes the issues worth raising, even briefly. Examples of negative consequences include, but are not limited to: the fear of social stigma, the inability to obtain health insurance, and physical harm (or even death, particularly in the case of sharing information about domestic violence situations). Despite the challenges presented by privacy and confidentiality provisions, states have found ways to address these requirements and meet clients needs.

What other questions should be asked?

Questions One through Nine address some of the common issues that arose during the background research for this paper. However, there are numerous other questions that states and localities should consider. Examples of other important questions include: Should drug testing be used to identify substance use among TANF recipients? What can be done to help medical professionals understand the implications of their assessment or diagnostic findings? Is gaming the system a problem?

Future Directions

The issues raised in this paper suggest that states and localities face a number of decisions in selecting an approach to screening and assessing TANF clients for unobserved barriers to employment. The paper also offers examples of how some states and localities have answered questions related to screening and assessment. However, the issues and discussion presented here generate a number of questions that require additional information to fully address. This suggests that, regardless of the chosen strategy, states, localities, and the federal government should consider incorporating data collection into approaches implemented and plan future research related to strategies for identifying barriers to employment. Perhaps most important among future research questions are those that shed light on the effectiveness of different approaches to screening or assessment of TANF clients for barriers to employment. Additionally, many questions remain regarding the factors that may influence the effectiveness of different approaches.

Introduction

With welfare reform it is now more important than ever to identify and address barriers to employment.

The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) eliminated the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) cash entitlement program and the Job Opportunities and Basic Skills (JOBS) training program, and replaced them with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant. TANF includes both cash assistance and welfare-to-work programs and differs from the former AFDC/JOBS program in that it is a temporary cash assistance program which has the explicit goal of moving families from welfare to work. This employment mission is reinforced by work participation and time limit requirements two key provisions of the federal welfare law which hold important ramifications for welfare recipients, especially those with significant barriers to employment.

Under this system of welfare reform, it is now more important than ever for states to use the flexibility provided under PRWORA to find new ways to help TANF recipients with health conditions, disabilities, or barriers to employment make the transition from welfare to work. To do this, TANF agencies must consider implementing strategies to identify the barriers that are inhibiting or prohibiting this transition. Once barriers are identified, welfare agencies and their partners can develop appropriate service strategies to meet the needs of clients so that they can find and maintain employment and transition off welfare.

Implementing identification and service strategies to address barriers to employment within the complex structure of the welfare systemwhich involves a number of function and partnersis no small task. As welfare agencies consider how best to serve recipients with health conditions, disabilities, or barriers to employment they will likely need to consider the flexibility presented by TANF to develop policies and programs as well as consider how best to use their partners in this endeavor. Partners may include both government entities and the community-based organizations that often serve as the providers of work or barrier-specific services for welfare recipients. When considering partners and service options, TANF agencies may also look to the Welfare-to-Work Grants program. This program, which offers funding to state and local workforce development agencies through the U.S. Department of Labor, is intended to address the needs of the hardest-to-serve TANF clients both while on welfare as well as once they are no longer eligible for cash assistance.1

This report discusses issues related to the development and use of screening and assessment practices (including the use of formal tools) to assist in the identification of disabilities and barriers to employment among TANF recipients. The disabilities and barriers faced by remaining TANF recipients are diverseranging from low basic skills and learning disabilities, to substance abuse and mental health problems, developmental disabilities, and physical disabilities. Although each of these presents challenges for TANF recipients faced with the transition from welfare to work, this report focuses on four of these barriers:

Substance abuse problems;

Mental health problems;

Learning disabilities; and

Domestic violence situations.

This report focuses on this limited list of barriers because prevalence estimates indicate they are common among TANF recipients and because they are often not easily observed by program staff and therefore pose additional identification challenges. However, the lack of discussion of other barriers in this report does not in any way diminish their importance or severity. Additionally, although not addressed specifically here, TANF staff frequently note that many recipients face multiple barriers to employment. Many recipients are believed to face complex situations that may include barriers such as lack of education or work experience along with a less obvious barrier, or the co-occurrence of unobserved barriers such as substance abuse and domestic violence. To the extent that these challenges present barriers to obtaining and maintaining employment, TANF agencies must develop new strategies for identifying these barriers and providing services to assist the client with her quest for self-sufficiency.

This report is organized to address key questions that should be considered as states and localities grapple with the challenge of identifying the unobserved barriers to employment facing TANF recipients remaining on welfare. TANF agencies do not face this challenge alone and may find advantages in involving, or in fact may need to involve, partner agencies. Therefore, this report includes questions that TANF agencies and/or their partners may need to consider. It is structured so as to allow readers to consider either the entire range of questions presented or focus on a particular question of interest. Specifically, the questions addressed here are:

Barriers, Screening, and Assessment: How are we using these terms?

Why should TANF agencies consider screening or assessment?

What policy opportunities and limitations are presented by TANF?

How can the case management process aid in identifying unobserved barriers to employment?

Are there tools that can be used to identify barriers to employment?

When should screening or assessment occur?

Who should conduct screening and assessment?

What training issues are related to screening and assessment?

What issues related to privacy and confidentiality should be considered?

What other questions should be asked?

To varying degrees, states and localities are already in the process of examining these questions and experimenting with different approaches and practices. Examples of these approaches are included throughout the report for illustrative purposes only. They are neither best practices nor suggested approaches. In fact, few have been evaluated and little is known about their effects, intended or unintended. Nonetheless, they provide valuable food for thought as TANF administrators tackle this challenge.

1 The Welfare-to-Work Grants Program was authorized by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. For additional information about this program see Greenberg 1997 and Perez-Johnson and Hershey 1999.

Methodology

This report reviews issues related to developing and implementing screening and assessment approaches and offers a review of tools that may assist in this process. Identification of the issues to be considered, as well as the tools currently being used to screen or assess for barriers, was primarily based on a series of semi-structured telephone interviews with:

Selected state TANF agency officials, and

"Experts" in particular areas of interest (specifically substance abuse and mental health problems, learning disabilities, and domestic violence).

Respondents were identified through Urban Institute contacts and a review of relevant literature. This process was not intended to systematically uncover screening, assessment, or identification practices used in all states.2 Instead the objective was to identify approaches and tools used in TANF agencies or tools used in other programs that could be used in TANF agencies. (Although other [non-TANF] agencies have been conducting assessments for some time, many experts were hesitant to recommend tools for use by TANF agencies, believing instead that TANF staff should refer clients they suspect may have a particular barrier to a specialized agency that serves such clients for assessment and diagnosis by a trained professional. 3 ) To accomplish this task, we spoke with 65 knowledgeable individuals between December 1999 and April 2000, including TANF and other state and federal government agency officials, researchers, practitioners, and association representatives.

Screening and assessment are on-going and dynamic processes. However, the telephone interviews allowed for a limited review of the range of different points in a TANF client's experience when screening or assessment might occur. For this report, we focused primarily on identification efforts that exist within a TANF agency (although these too may occur at multiple points in time). Where available, information about additional assessment efforts outside of the TANF agency is also included. Further exploration of the complete range of opportunities to conduct screening, as well as in-depth assessment or diagnosis of specific barriers or disabilities, will be a primary objective of the case studies undertaken in the next phase of this project. Services provided in response to assessments will also be a focus of the case studies and are not addressed in this report.

2 The American Public Human Services Association has undertaken a 50-state survey that includes identifying screening and assessment tools used by TANF agencies.

3 See additional discussion of this issue under Question Five.

Question One: Barriers, Screening, and Assessment: How are we using these terms?

Examining issues associated with identifying barriers to employment among TANF recipients is complex in part because there is little common use of terms. Fundamental confusion over the use of terms makes discussing barriers, identifying and designing identification approaches, and delivering services difficult. Clarifying how TANF and other systems define barriers and what is meant by screening and assessment are important first steps in developing effective strategies and partnerships. Given this lack of uniform definitions and terms, this section describes and clarifies our use of the terms "unobserved barriers," "screening," and "assessment" for the purposes of this report. This report does not try to impose standard definitions of these terms or reconcile varying definitions used by others. In discussing barriers it is important to recognize that not every health condition, disability, or personal circumstance presents a barrier to employment and that further, TANF agencies' primary concern lies only with those conditions, disabilities or circumstances that inhibit or prohibit the effect transition from welfare to work and self-sufficiency.

What Barriers do TANF Recipients Face?

TANF recipients continuing to be involved in the welfare system face a range of disabilities and barriers to employment and self-sufficiency. Some of these are barriers with which the TANF system has experience identifying (i.e., lack of transportation or child care, low educational attainment, lack of work experience). However, as TANF caseloads have declined and the more job-ready recipients have left welfare, TANF agencies now face the challenge of identifying and addressing different issues and barriers than they did in the past - health conditions, disabilities, and barriers to employment that are often unobserved. It is this new challenge that has expanded the interest in screening and assessment approaches.

Knowing which barriers should be the focus of identification efforts is an initial challenge faced by states and localities. As will be discussed in Question Two, estimates of the prevalence of different barriers, including substance abuse and mental health problems, domestic violence situations, and learning disabilities, among TANF recipients vary. In fact, many welfare agencies have little specific data indicating the challenges faced by their clients and the extent to which these challenges represent barriers to employment. Despite this, there is a common belief that welfare recipients are "harder-to-serve" than they were in the past and that the challenges they face are in some way prohibiting or inhibiting their transition from welfare to work.

Identifying barriers to employment faced by remaining welfare recipients is a new challenge for TANF agencies.

In many ways, identifying the challenges these remaining welfare clients face represents a new challenge to TANF agencies and their partners. The clients who have been the focus of welfare-to-work programs and who have already left welfare were more likely to have job skills and some work experience than those remaining on welfare. Additionally, although TANF clients with significant barriers to employment were likely to be exempt from participation in the JOBS program, many states have changed their policies to require those formerly exempt recipients to participate in work activities under TANF.4 This challenge to welfare agencies is further compounded by the time-limited nature of federal cash assistance under TANF.

Regardless of specific estimates, or lack thereof, each of the barriers faced by TANF clients is important. They range from lack of adequate transportation and child care, to serious physical disabilities, and caring for children with serious disabilities. TANF agencies vary in their experience dealing with these different barriers. For example, most TANF agencies have historically offered assistance with transportation or child care if they present a barrier to work or participation in required activities. TANF agencies also have experience determining if the lack of education poses a barrier to employment.

As TANF agencies have incorporated methods of identifying barriers that are more obvious, or with which they have experience, they are now beginning to grapple with how to identify the less obvious disabilities or barriers that continue to inhibit TANF recipients' transitions to work and self-sufficiency. Because some barriers - such as substance abuse and mental health problems, domestic violence situations and learning disabilities - are not as obvious to TANF agency staff, or may not be observed, they can be referred to under the broad heading of "unobserved barriers." When TANF agency officials describe clients as "hard-to-serve," these are some of the barriers clients face.

There are a variety of reasons barriers might be unobserved.

Why are some barriers "unobserved?"

Barriers might be less obvious, hidden, or unobserved for a variety of reasons. For example, the recipient may not be aware of or fully understand why she is unsuccessful in her quest to obtain employment. A client might acknowledge that she often feels sluggish or has a hard time arriving at work promptly but be unaware that these are possible symptoms of depression. Additionally, some clients may be in denial regarding a barrier such as substance abuse or domestic violence.

Another reason some barriers are unobserved is that, although a client is aware of the problem, she may be hesitant to disclose it and in fact may make special efforts to keep the problem from being revealed. Examples of this include clients who do not want to be labeled or have the stigma associated with a problem such as substance abuse or who are afraid of additional violence if they reveal a domestic violence situation. Yet another reason a barrier may be unobserved is that clients may be concerned that they are in jeopardy of having their children removed from the household if they disclose a barrier such as substance abuse.

Regardless of the reason, these situations require that TANF agency staff employ different approaches to uncover barriers than they might have employed in the past. Simple reliance on standard past practices of self-dis-closure or medical verification may not be sufficient to identify "unobserved" barriers.

What unobserved barriers are considered in this report?

TANF recipients face a wide range of personal issues and barriers to employment, many of which are unobserved. Although each is important and complex, this report focuses on four commonly unobserved barriers:

Substance abuse problems;

Mental health problems;

Learning disabilities; and

Domestic violence situations.

TANF agencies and their partners need to be clear with each other regarding how they define or conceptualize these (and other) barriers. For example, TANF agencies are generally concerned about issues that present barriers to employment. Therefore, although the mere existence of a mental health problem might warrant action by a mental health agency, this problem is primarily important to TANF agencies only in so far as it presents a barrier to employment. Similarly, although substance abuse treatment professionals consider any substance abuse problem deserving of attention, TANF agencies are interested to the extent it presents a barrier to employment.

Additionally, when discussing barriers partner agencies need to be clear about the meaning of different terms. For example, there are several proposed definitions of learning disabilities, yet learning disability experts we spoke to noted that learning disabilities are frequently confused with low educational attainment or literacy problems, as well as mild mental retardation. Further, "mental health problem" is a broad term encompassing a number of specific conditions including depression, anxiety disorders, bi-polar disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), to name a few. Similarly, what constitutes "domestic violence" varies and may include physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.5

4 Additionally, because of the less stringent participation requirements under JOBS, although not always formally exempt, clients with significant barriers to employment were less likely to be fully engaged in the JOBS program. See also Thompson, et al., State Welfare-to-Work Policies for People with Disabilities: Changes Since Welfare Reform. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, October 1998.

5 Domestic violence experts note that domestic violence differs from the other barriers addressed in this report in that it is a situation imposed on the individual, not an illness, addiction, medical condition, or disability.

What do We Mean by 0 and 0

For the purposes of this report, screening and assessment fall within the broad category of approaches used to identify or uncover barriers to employment. Identification efforts may include the use of case management techniques to elicit disclosure of a barrier, the use of formal or informal screening and assessment tools (discussed in Questions Four and Five), or clinical diagnosis. Because TANF agencies are not expert in diagnosing specific conditions, nor are their staff generally trained as clinicians or social workers, the level of identification undertaken by TANF agencies is likely to fall under the broad headings of screening or assessment. Below we clarify our use of these terms in this report. However, it bears noting that different organizations use these terms differently and, just as TANF agencies and their partners need to clarify how terms used to describe barriers are used, so do they need to clarify terminology used regarding identification.

What do we mean by "screening?"

The use of the term "screening" in this report refers to a process of determining if an individual is "at risk" of a certain condition or barrier. Screenings are intended to determine the likelihood that a person requires additional assessment to uncover a particular barrier. Screening as used here is not considered a definitive decision that a person faces a particular problem or condition - that would be a diagnosis6 - or even a comprehensive attempt to uncover a barrier. Screening tools are often described as inexpensive, requiring no training for staff to administer,7 and requiring little time to implement.

What do we mean by "assessment?"

The term "assessment," as used in this report, includes both specific efforts to identify barriers, as well as an on-going process of determining what barriers an individual faces. Assessment might include using a tool to identify a particular barrier, or could be a more general process of monitoring progress and analyzing (or assessing) why expected progress is not achieved. If a screening determines that an individual is likely to have a substance abuse problem, assessment will help confirm or deny the problem. Assessment for a specific barrier differs from screening in that it is more definitive and likely requires some training to implement and interpret results. However, it does not replace formal diagnosis. Conclusive determination that a problem exists, and determination of its extent, requires clinical assessment or diagnosis by a professional.

6 Diagnosis is a formal medical determination requiring professional training and is often required for insurance purposes or program participation. Given that this level of identification is not likely to occur within TANF agencies, it is not discussed in detail.

7 This does not alleviate the need for training on related issues such as awareness, handling information obtained through screening, or making appropriate referrals based on screening information, discussed further in Question Eight.

Question Two: Why should TANF agencies consider screening or assessment?

While a few states have been screening and assessing clients for health conditions, disabilities, and barriers to work for several years, there are a number of reasons why there is a growing interest in identifying and addressing unobserved barriers to employment. The overarching motivation for uncovering barriers is to fulfill the employment objectives of TANF - if a TANF agency is to fulfill these objectives it likely must identify issues that prohibit clients from making a successful transition from welfare to work. Once barriers to employment are identified, TANF agencies and their partners can develop programs and services to assist clients in their quests to successfully obtain employment, retain jobs, and eventually transition off welfare.

Prevalance estimates indicate high rates of unobserved barriers among TANF clients.

As welfare caseloads have declined, many of the remaining TANF clients are considered hard-to-serve and may require more help to obtain employment. Prevalence estimates presented in this section indicate high rates of unobserved barriers among TANF clients. Additionally, as TANF agencies have successfully moved clients from welfare to work, they are gaining new insights regarding the barriers that inhibit job retention and thus are motivated to address barriers in an effort to promote long-term self-sufficiency and reduce recidivism among clients.

With TANF's emphasis on moving clients from welfare to work and self-sufficiency, TANF agencies have more incentive than in the past to identify and address unobserved barriers to employment. No longer are TANF agencies liberally exempting clients facing obstacles to participation and employment from participation requirements. States we spoke with were acutely aware that participation incentives are reinforced by legislative or policy requirements such as federal work participation requirements, time limits, state TANF policies, and the Family Violence Option. Additionally, civil rights legislation, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, requires that TANF programs make reasonable accommodations for persons with disabilities, including three of the four unobserved barriers to employment addressed in this report.

Before moving to additional discussion of legislative and policy incentives related to identification of barriers, it is important to note that such efforts should be undertaken with care. Although the incentives to identify barriers to employment are clear, and in many cases early identification allows more time for services to assist clients, welfare agencies and their partners must be cognizant of the potential harm that may result from attempts to identify or mitigate barriers. This is particularly important in the case of domestic violence situations. Although a client may be exempt from certain program requirements if she is a victim of domestic violence, disclosing this fact and taking steps to address this issue must be done in a manner that does not further jeopardize her safety.

How do Legislation and TANF Policies Provide Incentives to Screen and Assess?

Title II of the ADA of 1990 "is intended to protect qualified individuals with disabilities from discrimination on the basis of disability in the services, programs, or activities of all State and local governments."8 The ADA defines "disability" as a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities, and the law specifically requires state and local governments to make reasonable accommodations when necessary to avoid discrimination on the basis of disability.9 Of the four barriers to work considered here, three are disabilities covered by the ADA - substance abuse,10 mental health problems, and learning disabilities.11 States and localities designing and implementing screening and assessment approaches and referrals to services must ensure that they do not discriminate against qualified individuals with disabilities. State and local TANF programs may not use criteria that screen out or tend to screen out an individual with a disability from participating unless such criteria can be shown to be necessary for the service or program. 12 Although the states we spoke to did not specifically identify this as an issue they were grappling with, all states and localities must ensure that their programs meet the guidelines of the ADA. 13

States we spoke to identified several reasons why they developed or were newly developing screening and assessment processes for TANF clients. The reason cited most frequently was meeting the increasing annual federal work participation requirements. In fact, it bears repeating here that welfare agencies are primarily concerned with identifying unobserved disabilities only in so far as they are barriers to employment and participation in work activities. TANF caseload declines are believed to have left many states with an increasing proportion of recipients facing challenges in their efforts to transition from welfare to work. Although states have generally had no trouble meeting work participation rate requirements to date, as increasing proportions of long-term TANF recipients face barriers to work, states are anticipating that meeting federal work requirements will be increasingly difficult.

Time limits provide incentives for TANF agencies to identify unobserved barriers to employment

Many states also indicated that approaching time limits are another reason for increased emphasis on screening and assessing TANF clients for unobserved barriers to employment. Many states, and particularly those with time limits shorter that the federal 60-month limit, are beginning to consider the ramifications of time limits on meeting the needs of clients remaining on TANF. Getting clients screened, assessed, referred, treated, and into work when they have a significant barrier to employment can take time. As the federal 60-month time limit approaches, more and more states will be faced with less and less time to remove or mitigate barriers to work for hard-to-serve TANF clients.

How does the Family Violence Option provide an incentive to screen and assess?

Another reason states mentioned for beginning or enhancing screening and assessment practices specifically related to domestic violence victims receiving TANF is the Family Violence Option (FVO). The FVO enables states that adopt this option to provide temporary waivers from work requirements for domestic violence counseling, safety planning, and other related services. States that adopt the FVO agree to:

Screen and identify individuals who are receiving assistance under TANF and who have a history of domestic violence while maintaining the confidentiality of such individuals;

Make referrals for counseling and supportive services; and

Waive program requirements, pursuant to good cause, such as time limits (for as long as necessary), if complying with the requirements would make it more difficult to escape from domestic violence or unfairly penalize the individual in light of her past or current experience with domestic violence.14

Thirty-two states had adopted the FVO and had all policies and procedures in place as of May 1999.15

8 U.S. Department of Justice. The Americans with Disabilities Act Title II Technical Assistance Manual Covering State and Local Government Programs and Services. Washington, DC: U.S. DOJ, undated.

9 See U.S. Department of Justice. 28 CFR 36.104, Americans with Disabilities Act. Washington, DC: U.S. DOJ, July 26, 1990.

10 Individuals currently using illegal drugs are not protected from discrimination under the ADA, however, the ADA does prohibit denial of health services or rehabilitation services to an individual on the basis of current illegal drug use if the individual is otherwise entitled to such services.

11 U.S. DOJ undated.

12 U.S. DOJ undated.

13 For more information see U.S. Department of Labor. How Workplace Laws Apply to Welfare Recipients. Washington, DC: U.S. DOL, May 1997, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Civil Rights Laws and Welfare ReformAn Overview. Washington, DC: U.S. DHHS, August 1999, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Technical Assistance for Caseworkers on Civil Rights Laws and Welfare Reform. Washington, DC: U.S. DHHS, August 1999.

14 Public Law No. 104-193, 104th Congress, 2nd Session, Section 402(a)(7). August 22, 1996.

15 Raphael, Jody and Sheila Haennicke. Keeping Battered Women Safe Through the Welfare-to-Work Journey: How are we Doing? Chicago, IL: The Center for Impact Research, September 1999.

How Common are These Barriers?

Yet another reason why TANF agencies who are not already doing so should consider screening and assessing is the prevalence of disabilities and barriers to employment among TANF recipients. A review of several studies with prevalence estimates for substance abuse, learning disabilities, domestic violence, and mental health problems, describe high rates of incidence - a compelling reason for states to enhance or adopt screening and assessment efforts.

Prevalence of Multiple/Co-Occurring Barriers. Many TANF clients face multiple (co-occurring) barriers to employment with some barriers more likely to co-occur than others. Several studies estimate the prevalence of multiple barriers to employment among welfare recipients. Although estimates vary, in part due to differences in definitions of barriers to work, estimates of the co-occurrence are still useful. In a review of several studies, Johnson and Meckstroth (1998) report that nationally 13 to 50 percent of welfare recipients experience multiple barriers - including two or more of the following: lack of child care, disabilities, domestic violence, emergency financial needs, housing instability, lack of health insurance, mental health or substance abuse problems, or lack of transportation - which may impede the ability to work.16

Using administrative data, staff focus groups, and client interviews, a recent study in Utah noted prevalence rates for the following barriers to work:

Clinical depression (42 percent)

Generalized anxiety disorder (7 percent)

Post-traumatic stress disorder (15 percent)

Learning disability (23 percent)

Physical health problems that prevent work (35 percent)

Poor work history (30 percent)

Severe child behavior problems (23 percent)

Severe domestic violence within the last 12 months (12 percent)

The Utah study found that 92 percent of families faced at least one of these barriers to work with many families facing multiple barriers, 26 percent of families faced three barriers, and 37 percent faced four or more barriers to work with longer term welfare recipients reporting more barriers.17

Using the Urban Institute's National Survey of America's Families (NSAF) data for 1997, Loprest and Zedlewski (1999) found that 78 percent of current welfare recipients face one or more barriers to work - including one of the following six barriers:

Very poor mental health or health limiting work;

Education less than high school;

No work experience or having last worked three or more years ago;

Child under age one;

Caring for a child on Supplemental Security Income; or

English-language limitations.

Loprest and Zedlewski further found that 44 percent of current welfare clients face two or more of these barriers, and 17 percent of clients face three or more of these barriers to work.18

Not all barriers are as likely to co-occur as others. Citing a study by Olson and Pavetti (1996), Johnson and Meckstroth (1998) report that among clients with multiple barriers, low basic skills is the barrier most likely to co-occur, with mental illness, housing instability, domestic violence, and substance abuse also likely to co-occur.19 Johnson and Meckstroth (1998) also review past research and report that 42 to 54 percent of domestic violence victims receiving welfare also suffer from depression. Domestic violence is also likely to co-occur with substance abuse with estimates ranging from 19 to 38 percent of domestic violence victims also reporting drug and alcohol abuse or dependency.20

There is little debate that substance abuse is a common barrier faced by TANF recipients.

Prevalence of Substance Abuse. Estimates of the prevalence of substance abuse among welfare recipients vary widely (based on differing data sources and definitions of substance abuse), although there is little debate that this is one of the common barriers faced by TANF clients. A recent report by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) notes findings from a recent state survey indicating that "State TANF administrators consistently identified substance abuse among participants as a pervasive problem...."21 Additionally, substance abuse is considered a factor affecting TANF clients' ability to obtain and retain jobs and was included as one of the eligibility factors for the Welfare-to-Work Grants program designed to help hard-to-serve welfare recipients.

One study that reviewed past research reports estimates ranging from two percent for welfare recipients who sought treatment for substance abuse to 20 percent for welfare recipients who self-reported substance use.22

Another review of estimates notes that nationally five to 27 percent of welfare recipients have a substance abuse problem depending on how it is defined - narrowly where the individual is either an alcoholic or drug user or broadly where the individual is a possible alcoholic and/or drug user.23 Yet another summary notes that 6.6 to 37 percent of welfare recipients have a substance abuse problem depending on the measure used.24

Prevalence of Learning Disabilities. Learning disabilities are another commonly cited barrier to employment faced by TANF recipients. However, there is little consensus on a definition of a learning disability. Often issues of low educational attainment, illiteracy, and even developmental disabilities are grouped under the heading of learning disabilities. The lack of a common definition contributes to the range of prevalence estimates available.

Estimates of learning disability prevalence vary with Johnson and Meckstroth (1998) reporting that past national studies found 25 to 40 percent of welfare recipients have a learning disability or low basic skills. The TANF Program Second Annual Report to Congress reports that up to 40 percent of welfare recipients have a learning disability or low basic skills.25 State studies in Kansas, Utah, and Washington report that it is likely that 20 to 33 percent of welfare recipients have a learning disability with Washington suggesting that up to one-half may have a learning disability.26 While these figures seem quite high, Young (1997) suggests that women experience higher rates of learning disabilities as adults due to gender bias in their youth. Lack of diagnosis of a learning disability in youth results in fewer girls receiving the necessary special education, thus lending credibility to higher estimates given the predominance among adult women, who are most commonly the heads of TANF households.27

Estimates of domestic violence situations vary whether based on current or lifetime victimization rates.

Prevalence of Domestic Violence. Domestic violence is a broad term used to describe abusive or aggressive behavior by a person in an intimate relationship with the victim and may be physical, sexual, or emotional.28 Estimates of domestic violence prevalence vary depending on whether current or lifetime victimization rates are measured. The Center for Impact Research - a leading domestic violence advocacy organization - reviewed five major research studies and reports that 20 to 30 percent of welfare recipients are current victims of domestic violence.29 Similarly, in a review of national studies Johnson and Meckstroth (1998) found that 24 percent of welfare recipients have been "physically victimized or threatened by their current partner sometime during the past five years." Yet another summary by Danziger et al. (1999) notes both current and lifetime domestic violence rates ranging from 10 to 31 percent and 48 to 63 percent, respectively. The only other lifetime prevalence rates we identified are state and local estimates reported by Johnson and Meckstroth (1998) with lifetime domestic violence rates ranging from 29 to 65 percent.

Prevalence of Mental Health Problems. Mental health problem is another broad term used to describe what may be a barrier to work for many TANF recipients. Like learning disabilities and domestic violence, the term mental health problem actually encompasses a number of specific conditions including clinical depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and others. In estimating prevalence, many studies report about mental health problems or impairments generally while others measure specific mental conditions.

Using the 1997 National Survey of America's Families (NSAF) data, Loprest and Zedlewski (1999) found that 22 percent of current - and 18 percent of former - welfare recipients said they had very poor mental health. Similarly, Sweeney (2000) summarizing recent research, notes that 20 percent of former welfare recipients who are not working have mental health impairments. Other studies estimate different prevalence rates depending on whether welfare clients meet the diagnostic criteria for depression - 6 to 23 percent - or whether welfare clients show symptoms of depression - 13 to 39 percent.30

Estimates of prevalence for specific mental illnesses vary nationally and from state to state. A review of national prevalence rates for specific mental illnesses indicates that the following percentages of welfare clients met definitions of specific mental health problems. 31

Major depression (27 percent)

PTSD (15 percent)

General anxiety disorder (7 percent)

Michigan found 25 percent of welfare recipients - compared to over 40 percent in Utah - had major or clinical depression. Michigan and Utah found similar rates of PTSD and general anxiety disorder at 14 and seven percent, respectively.32

16 Johnson, Amy and Alicia Meckstroth. Ancillary Services to Support Welfare to Work. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, June 1998.

17 Barusch, Amanda Smith, Mary Jane Taylor, Soleman H. Abu-Bader, and Michelle Derr. Understanding Families With Multiple Barriers to Self Sufficiency. Final Report submitted to Utah Department of Workforce Services. Salt Lake City, Utah: Social Research Institute, February 1999.

18 Loprest, Pamela J. and Sheila R. Zedlewski. Current and Former Welfare Recipients: How Do They Differ? Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, November 1999.

19 Johnson and Meckstroth 1998.

20 Johnson and Meckstroth 1998.

21 The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (in partnership with the American Public Human Services Association). Building Bridges: States Respond to Substance Abuse and Welfare Reform. Washington, DC: CASA, August 1999.

22 Sweeney, Eileen P. Recent Studies Indicate That Many Parents Who Are Current or Former Welfare Recipients Have Disabilities or Other Medical Conditions. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 2000.

23 Johnson and Meckstroth 1998.

24 Danziger, Sandra, Mary Corcoran, Sheldon Danziger, Colleen Heflin, Ariel Kalil, Judith Levine, Daniel Rosen, Kristin Seefeldt, Kristine Siefert, and Richard Tolman. Barriers to the Employment of Welfare Recipients. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Poverty Research and Training Center, April 1999.

25 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Program: Second Annual Report to Congress. Washington, DC: August, 1999.

26 Sweeney 2000.

27 Young, Glenn, H., Jessia Kim, and Paul J. Gerber. Gender Bias and Learning Disabilities: School Age and Long-Term Consequences for Females. Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, Vol. 9, No. 3. Pittsburgh, PA: Learning Disabilities Association, 1997.

28 Johnson and Meckstroth 1998.

29 Raphael and Haennicke 1999.

30 Johnson and Meckstroth 1998.

31 Kramer, Fredrica D. Serving Welfare Recipients with Disabilities. Washington, DC: Welfare Information Network, January 1999.

32 Sweeney 2000.

Question Three: What policy opportunities and limitations are presented by TANF?

The devolution of policy making authority granted under PRWORA encourages state and local creativity and flexibility to identify and address unobserved barriers to work among the TANF population. This section discusses the opportunities and limitations presented by federal TANF policies that states face in developing screening and assessment approaches. In particular, we consider four key TANF features - 1) the uses of federal TANF funds and the definition of assistance, 2) time limits, 3) work requirements, and 4) the Family Violence Option.33

When developing screening and assessment policies and approaches state and local TANF agencies and their partners need to clearly understand the intricacies of each policy requirement, and the mix of constraints and opportunities they offer. The intent of this section is to highlight key features of TANF policy that may influence decisions about approaches to screening, assessment, and service provision. In an effort to illustrate some of the program and policy choices states have made, this section offers some examples. However, it is by no means a comprehensive review of the combinations of policies states have adopted, nor does it present the range of combinations states may want to consider.34

33 For a more complete understanding of TANF guidelines, see Public Law 104-193, and TANF regulations at 45 Code of Federal Regulations Parts 260-265. See also regulation summaries prepared by Greenberg and Savner 1999 and Schott, et al. 1999.

34 For additional information on the uses of TANF funds see, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Family Assistance, Helping Families Achieve Self-Sufficiency: A Guide on Funding Services for Children and Families through the TANF Program, www.acf.dhhs.gov/programs/ofa/funds2.htm. Washington, DC: DHHS, undated.

What Opportunities and Limitations are Presented by the Family Violence Option

The Family Violence Option (FVO) may provide states adopting this option protection from penalties that might otherwise be imposed for not meeting work participation requirements or for failing to comply with federal time limits. The FVO provides states with the flexibility to grant families temporary waivers from work and other program requirements without fear of penalties. Waivers may be granted to allow families to pursue domestic violence counseling, safety planning, and other related services.49

However, in order to qualify for this safeguard, states that grant exemptions to domestic violence victims must certify that they have and enforce procedures to screen and identify individuals who have a history of domestic violence and make referrals for counseling services while maintaining confidentiality.50 If a state meets these federal requirements and exceeds the 20 percent limit on the number of clients that can receive federal assistance beyond 60 months because the state is providing waivers to domestic violence victims, the state will not be penalized.51 Similarly, if a state fails to meet the required work participation rate because of good cause waivers to the work requirement granted to domestic violence victims, it will also not be penalized.

49 For the purposes of the FVO, a family must have "...an individual who is battered or subjected to extreme cruelty." See TANF Final Regulations, Section 260.51.

50 See TANF Final Regulations, Section 260.55 for additional details regarding federal recognition of domestic violence good cause waivers.

51 Schott, et al. 1999.

What Opportunities and Limitations are Presented by the Provision of Federal TANF 0

Key to understanding the flexibility offered and constraints imposed by TANF is the concept of TANF "assistance." This is important because two of the more widely talked-about aspects of TANF policy - time limits and work requirements - apply when federal TANF "assistance" is provided. Therefore, decisions about providing services are influenced by whether or not the service falls within the definition of "assistance."

The final TANF regulations provide a fairly narrow definition of "assistance," thus broadening the range of services states and localities can offer clients without subjecting them to time limits and work participation requirements. "Assistance" includes cash payments, vouchers, and other non-cash benefits designed to meet a family's on-going, basic needs. There are specific exclusions from this definition including supportive services to employed families, short-term benefits,35 wage subsidies to employers, and other services that do not provide basic income support.

The federal definition of "assistance" allows states attempting to identify barriers latitude in the services they can offer without subjecting clients to time limits and work participation requirements.

This definition offers states undertaking efforts to identify barriers to employment some latitude in providing a range of services. For example, counseling and case management services - services that do not provide basic income support but that are thought to be important for clients with unobserved barriers to employment - are examples of services excluded from the definition of "assistance." Therefore, states have the flexibility to provide these services without subjecting clients to federal time limits or work participation requirements. However, if for example, federal TANF funds are used to provide a cash benefit while a client is in counseling, time limits and work requirements do apply to that family.

35 States may use TANF funds to provide "short-term" benefits or support "short-term" services for an "episode of need" - defined as four months or fewer - without being considered assistance.

Are services funded by state dollars considered "assistance?"

If a state wants to provide benefits or services that fall within the definition of "assistance," but does not want to subject the family to the consequences of the 60-month federal time limit and federal work requirements, the state may choose to fund benefits and services with state Maintenance of Effort (MOE) dollars. Spending of state funds is explicitly addressed in PRWORA through MOE requirements. In general, states are required to maintain a historic level of spending if they want to receive their maximum TANF block grant. The use of MOE funds separate from federal TANF block grant funds (through Separate State Programs) allows states to provide services, even those that fall within the definition of assistance, but without triggering other requirements. The flexibility offered by Separate State Programs allows states and localities to provide services such as substance abuse or mental health treatment, or educational programs to meet the needs of those with learning disabilities, without subjecting these recipients to federal time limits. While the flexibility exists to create Separate State Programs, states must choose between many competing interests regarding how to spend their state funds.

What Opportunities and Limitations Arepresented by Time Limits?

Both federal and state time limits can affect TANF recipients' opportunities to receive services necessary to successfully transition from welfare to work. Many perceive time limits as a motivating factor for TANF agencies to provide services and clients to undertake steps to change their lives. However, for clients with unobserved barriers to employment, leaving welfare and achieving self-sufficiency within 60 months as required by PRWORA may be a significant challenge.

In some states, clients face the challenge of leaving welfare in less than 60 months. PRWORA allows states to impose time limits shorter than 60 months - an option 23 states have exercised.36 State time limits vary, including being as short as 12 months in Texas (for recipients with 18 or moremonths of recent work experience and a high school diploma, GED, or certificate from a vocational school37 ) and 18 months in Tennessee.38 Both types of time limits increase the urgency around removing or mitigating barriers to work. For instance, a client with a substance abuse problem must have her problem identified, be referred to services, receive and successfully complete services, and ideally leave welfare for work before 60 months has elapsed, or in even less time in many states.

States with shorter time limits might consider making screening and assessment part of initial intake in an attempt to identify and address barriers to employment as soon as possible. For example, concerned about the 36-month state lifetime limit on cash assistance, Utah's state legislature mandated the addition of the four CAGE questions - a common set of questions used to identify substance use problems - to their comprehensive screening tool in an effort to identify clients with substance abuse problems earlier in the process. Officials in Utah said that TANF clients often mask substance abuse problems. However, identifying unobserved barriers as early as possible is very important since the agency has 36 months to treat clients and help them find work.

36 States that established state time limits under a pre-PRWORA federal waiver that differ from the federal time limit defined under PRWORA can continue to operate under the waiver if they choose. For the duration for which the waiver was granted, the state is not required to comply with the provisions of PRWORA that are inconsistent with the waiver (so long as they noted this "inconsistency" in the state TANF plan). When the waiver expires, the state must impose the federal time limit.

37 Gallagher, L. Jerome et al. One Year after Federal Welfare Reform: A Description of State Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Decisions as of October 1997. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, June 1998.

38 After 18 months of assistance in Tennessee, a family must wait at least three months before becoming eligible for another 18 months of assistance. Families in Tennessee are allowed a total of 36 months of TANF assistance.

Can TANF agencies fund services for more than 60 months?

The 60-month limit applies only to clients receiving federal TANF "assistance." Months during which clients receive benefits that fall outside of the definition of assistance, or services that are exclusively state funded, do not count toward the federal time limit. Therefore, the use of separate state funds can serve as a mechanism for effectively "stopping" a client's federal time clock.39 States may provide services for a total of more than 60 months by funding services in some months with federal TANF funds and in others with state dollars. This option may be important as TANF agencies are faced with serving clients with unobserved barriers to employment who may require more than 60 months to make their journey from welfare to work.

Another way to use state funds to offer more than 60 months of services is by supporting clients with state funds once they have reached the federal time limit. States that are willing to use their own funds to provide services can allow families to receive welfare beyond 60 months. For example, Maine, Michigan, and New York have agreed to pay for TANF benefits beyond 60 months using state funds to support families who are unable to transition off of welfare despite participating in required programs or services.

39 Note that the client may still be subject to a shorter, state-imposed time limit which may supercede the federal limit.

What is the 20 percent hardship exemption?

PRWORA allows states to exempt up to 20 percent of its caseload from the federal time limit due to hardship.

In addition to the option of funding services and benefits with state funds, PRWORA also gives states the flexibility to continue to fund services with federal TANF funds beyond 60 months for up to 20 percent of its caseload due to "hardship." PRWORA further gives states the flexibility to define what constitutes a hardship. In other words, 20 percent of TANF families who reach the five-year federal time limit and qualify under state-defined "hardship" criteria may continue to receive federally funded TANF benefits and services.

This provides states the opportunity to determine what disabilities or barriers to employment may exist among the remaining TANF caseload, and define hardship such that these individuals receive a time limit exemption. However, many states have little systematic information about the barriers faced by TANF recipients and must consider which barriers to deem worthy of a hardship exemption, while subjecting other clients to benefit termination. States with 60-month time limits will not have clients who reach this limit until August 2002, and, as a result, it is not surprising that many states are in the early stages of thinking about who should be covered by the federal 20 percent hardship exemption rule.

What other time limit exemptions or extensions exist?

Technically, the only exemption to the federal time limit is the 20 percent hardship exemption mentioned above. However, states have established exemptions to their shorter state time limits. Many of these exemptions are given to clients due to age, disability, or the need to care for a disabled household member. It is important to note that although a person may be exempt from a state time limit, if during this time she receives federally funded TANF "assistance," such as a cash benefit funded by the TANF block grant, the 60-month federal time limit will still apply.

Arkansas offers an example of how a state exempts clients from a shorter state time limit while being assessed. In Arkansas, if a caseworker suspects a client may have a learning disability, the client is placed in deferred status and referred to the Arkansas Rehabilitation Services (ARS) for assessment. While in deferred status, the client's 24-month state time clock is not counting. If the assessment determines that the client is "too impaired" for ARS services, the client remains deferred and her 24-month clock remains stopped. When Arkansas first began TANF, the clock continued to run for those temporarily deferred from the work requirement. However, state officials reported that TANF staff felt this was a poor policy and pushed for a legislative amendment (passed last year) to allow the state time clock to stop and to retroactively reset the clock for those identified with learning disabilities prior to the amendment.

An alternative to exempting recipients from time limits is to offer an extension to the eligibility period. As noted previously, states may effectively extend welfare eligibility by granting a "hardship" exemption or continuing to provide services with state funds. States also have the flexibility to offer extensions to shorter, state time limits. Twenty states offer extensions to time limits when the adults in the family have made a good faith effort to find employment but remain unemployed or underemployed.40 Domestic violence is the most common reason for extensions - unemployment or underemployment are the second.

Utah illustrates how a state with a time limit shorter than 60 months can use extensions to bridge the gap between state and federal time limits. In Utah, the state time limit is 36 months. In January 1997, the state legislature approved a bill that allows 20 percent of TANF recipients, or about 2,000 families, to exceed the state's three-year time limit.41 Therefore, this 20 percent is now eligible for state TANF benefits between 36 and 60 months. 42 Then, after 60 months, this group may also be eligible for the 20 percent federal hardship exemption, should Utah choose to define hardship to include them. Some of the state extension provisions - such as those in Maine, Michigan, and New York - enable TANF recipients to receive benefits beyond five years. However, in making decisions about time limit extensions, states must consider the fact that these extensions may prove costly in the long run.

It is widely assumed that declining caseloads will leave higher proportions of TANF clients with health conditions, disabilities and other circumstances that may negatively affect their ability to find or keep a job, presenting a greater challenge to states to address these issues within the time remaining. Should this assumption prove true, states may need to increasingly seek creative solutions to identify and address unobserved barriers to work using the flexibility allowed through federal and state time limit policies.

40 Center on Law and Social Policy and Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. State Policy Documentation Project, February 2000.

41 State Capitals Newsletters. Utah House Passes Bill Extending Welfare for Violence Victims. Public Assistance and Welfare Trends, Vol. 54, No. 5. Alexandria, VA: State Capitals Newsletters, January 2000.

42 Thus, this law allows 20 percent of recipients to exceed the 36-month time limit.

What Opportunities and Limitations are Presented by Work Requirements?

There are two key aspects of work requirements that must be considered when thinking about how TANF work policies affect clients with unobserved barriers to employment. First, states face work participation rates with strict federal requirements regarding how to calculate the rates. Second, states have the flexibility to allow clients to engage in activities beyond those that count toward the rate calculation. Thus, the list of allowable work activities defined by a state may be broader than the activities defined in PRWORA as countable toward work participation rates.43

States vary in terms of both the types of work requirements they impose on TANF recipients (i.e., how soon client must engage in activities and how many hours they must participate) and the types of work activities that are allowed to show compliance with the work requirement. Under federal law, TANF recipients are required to conduct some work activity within 24 months of receiving TANF, but the definition of the work requirement is left to states, and gives states the discretion to impose requirements sooner than 24 months. Below we discuss factors important to determining what activities TANF recipients may engage in and how this decision is influenced by federal work participation rate requirements.

43 States that defined work activities differently under a pre-PRWORA federal waiver than how they are defined under PRWORA can continue to calculate their work participation rate using the state's definition for the duration of the waiver (so long as they noted this "inconsistency" in the state TANF plan). When the waiver expires, the rate will have to be calculated based on the definition of work discussed in this report.

What is the work participation rate?

Federal law establishes the work participation rates that states must meet or face penalties44 (shown in Table 1). The participation rate calculations are quite complicated, but worth discussing here because they have figured prominently in the specific program and policy choices made by states. The calculation of a state's annual participation rate is based on the average of the state's monthly participation rates in that year and is calculated as the number of families receiving TANF "assistance" that include a working adult or an adult engaged in countable work activities (discussed below) for the required number of hours per week as a percentage of the number of families receiving TANF "assistance" subject to penalty for refusing to work in that month.45

Table 1: Annual Work Participation Requirements Under the TANF Block Grant

| Fiscal Year | All Families a | Two-Parent Families |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 40 percent | 90 percent |

| 2001 | 45 percent | 90 percent |

| 2002 | 50 percent | 90 percent |

Source: Greenberg, Mark and Steve Savner 1996.

a Note the all families rate is only for families in which there is an adult.