Jess Wilhelm, MA

Social & Scientific Systems, Inc.

Natasha Bryant, MA

LeadingAge

Janet P. Sutton, PhD

Social & Scientific Systems, Inc.

Robyn Stone, ScD

LeadingAge

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by the Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

We are grateful to Dr. Christine Bishop, who provided suggestions on the analysis and literature review, and Bryan Sayer for his advice and support in conducting statistical analysis. We would also like to acknowledge Heather Seid for her programming assistance. The project team is further grateful to our project officer, Marie Squillace, for her guidance throughout the course of this study.

Acronyms

The following acronyms are mentioned in this report.

| ADL | Activity of Daily Living |

| ASPE | HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation |

| BLS | Bureau of Labor Statistics |

| CNA | Certified Nurse Aide |

| DCWA-NC | Direct Care Worker Association of North Carolina |

| FPL | Federal Poverty Level |

| FT | Full-Time |

| FTE | Full-Time Equivalent |

| GED | General Equivalency Diploma |

| HHA | Home Health Aide |

| HHS | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

| HS | High School |

| KFF | Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation |

| MSA | Metropolitan Statistical Area |

| NCHS | National Center for Health Statistics |

| NHHAS | National Home Health Aide Survey |

| NHHCS | National Home and Hospice Care Survey |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PHI | Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute |

| PT | Part-Time |

| REF | Reference |

Introduction

After informal caregivers, home health and home care workers (referred to in this article as home health workers or home health aides [HHAs]) provide the majority of hands-on, personal care services to older adults and younger people with disabilities (Kaye, Chapman, Newcomer, & Harrington, 2006; Stone, 2004). These workers tend to have frequent, intimate contact with clients, often developing relationships with them and becoming an important source of emotional as well as physical support (Stone, 2004). The demand for home care has increased significantly over the past three decades. Elderly and younger consumers and their families prefer home and community-based services to the receipt of care in nursing homes. Four out of five elders who require long-term services and support live in the community and want to receive care in their own home (Butler, Brennan-Ing, Wardamasky, & Ashley, 2013). Federal and state policymakers have responded to this demand, as well as the potential for cost savings, by expanding home and community-based options in lieu of nursing home placements for disabled Medicaid beneficiaries. Home health care services covered by Medicare, Medicaid and commercial insurers have also expanded to address the post-acute care needs of individuals being discharged from hospitals more quickly than in previous years, or even bypassing a hospital stay entirely. The demand for this workforce is likely to grow even more over the next 30 years as the baby boom generation ages, the number of people with disabilities increases and the availability of caregivers decreases (Redfoot, Feinberg, & Houser, 2013).

The availability and stability of home health workers are essential to the success of home health and home and community-based services in meeting current and future demands in a high-quality and efficient manner. Today, agencies, consumers, and their families are challenged to recruit and retain workers due to low status, poor pay, and challenging working conditions (HHS, 2011; Benjamin & Matthias, 2004; Stone, 2004). Home health workers have high rates of turnover, estimated to range from 44 percent to 65 percent annually, depending on how turnover is measured (Seavey & Marquand, 2011). Ninety-seven percent of states responding to a 2007 survey reported that direct service worker (including nursing home and home care/personal care aides) vacancies and/or turnover constituted “a serious workforce issue,” up from 76 percent in 2005 (PHI & DCWA-NC, 2007).

Objectives

Job dissatisfaction, high turnover rates, and instability in the home health care workforce have negative consequences for consumers, providers, and policymakers. It is therefore important to understand the factors that contribute to this problem. The purpose of this study is to better understand whether and how key agency and worker-level variables, including job satisfaction, affect a home health worker’s decision to leave the job. The analysis uses a modified version of the demand control/support model (described in detail below) to identify the key predictors of job satisfaction and then to assess the direct and indirect effects of job satisfaction as well as other variables on a worker’s intention to leave the job. By understanding the factors that drive home health workers’ job satisfaction and retention, it may be possible to identify organizational strategies and government policies to assist in retention of the home health workforce.

Overview of Job Satisfaction and Turnover Research

Most of the empirical research in the literature review examining job satisfaction and turnover intentions/turnover comes from nursing home studies with few that have looked at direct care workers across settings and fewer specifically examining the home care environment. While other factors also play a role, job satisfaction has been found to be a predictor of direct care workers’ intent to leave the job across long-term care settings (Sherman et al., 2008; Matthias & Benjamin, 2005; Decker, Harris-Kojetin, & Bercovitz, 2009; Castle, Degenholtz, & Rosen, 2006; Rosen, Stiehl, Mittal, & Leanna, 2011; Kiyak, Namaze, & Kahana, 1997; Castle, Engberg, Anderson, & Men, 2007). High turnover can have negative consequences for consumers and their families, employers, and policymakers. Workers who remain on the job may be more rushed because they are “working short” and, therefore, provide inadequate or unsafe care (Jobs with a Future Partnership, 2003; Dawson & Surpin, 2001). In addition, turnover and reduced availability of direct care staff make it difficult to provide continuity of care to clients. This lack of continuity disrupts the relationship building between the client and aides, an important contributor to quality of life for disabled individuals. It also limits the time for aides to understand clients’ needs and preferences (Wiener, Squillace, Anderson, & Khatutsky, 2009; Dawson & Surpin, 2001; Jobs with a Future Partnership, 2003; Butler, Wardamasky, & Brennan-Ing, 2012). Aides may be unable to adequately meet the needs of clients, resulting in poor nutrition, discomfort, secondary health conditions, and increased isolation (Kaye, Chapman, Newcomer, & Harrington, 2006). Clients may be turned away and denied access to care because there is not enough staff to meet the demand (Dawson & Surpin, 2001; Jobs with a Future Partnership, 2003). Worker shortages ultimately limit successful public policy implementation, as Medicare attempts to lower costs through the use of post-acute home health care and state Medicaid programs expand home and community-based services and attempt to integrate acute, primary, and long-term services and support for the dual-eligible population (those eligible for Medicare and Medicaid).

Most of the empirical research examining the relationship between turnover and quality has been conducted in the nursing home setting. High turnover rates of certified nursing assistants have been associated with poorer quality care for nursing home residents (Bostick, Rantz, Flesner, & Riggs, 2006; Castle et al., 2006; Castle & Engberg, 2005; Mittal, Rosen, & Leana, 2009). Bostick and colleagues found that higher worker turnover rates in nursing homes were correlated with greater use of physical restraints, catheters, and psychoactive drugs, more contractures, pressure ulcers, and quality of care deficiencies. Barry, Brannon, and Mor (2005) found that nursing homes with low turnover and high retention rates experienced lower pressure ulcer incidence rates relative to nursing homes with high turnover and high retention rates. While there are no published studies examining the effects of HHA turnover or other workforce quality measures on client quality of care, studies have highlighted the important role that a positive relationship between the client and the aides plays in quality of life outcomes (Eustis, Kane, & Fisher, 1993; Rodat, 2010).

Turnover also poses an economic burden on agencies and clients who hire their own home health workers. Stone (2004) cited Zahrt’s cost to replace home care workers. The total cost associated with each turnover was $3,362. This included the costs of recruiting, orienting, and training the new employee as well as the costs related to terminating the worker being replaced (e.g., exit interview, administrative functions, separation pay, unemployment taxes) (Zahrt, 1992 in Stone, 2004). Millions of dollars are spent on recruitment, orientation and training for new workers who then leave the job as well as hiring temporary, replacement workers to help agencies that are short-staffed (Mittal et al., 2009; Butler et al., 2012; Jobs with a Future Partnership, 2003; Dawson & Surpin, 2001; Wiener et al., 2009). Agencies also may experience loss in productivity, reduced morale, and increased stress among workers (Jobs with a Future Partnership, 2003). They can forgo income or lose income due to sales volume constricted by a lack of labor (Dawson & Surpin, 2001; Jobs with a Future Partnership, 2003).

It is critical to address workforce retention because these problems will probably be exacerbated in the future. The home health and home care industry is the fastest growing sector of the American economy. The number of home health worker jobs is projected to grow by 50 percent between 2012 and 2022, at rates four or five times that of jobs overall in the economy (BLS, 2012; Seavey & Marquand, 2011; PHI, 2014). The number of home health workers needed to meet demand is over 1.3 million by 2020 (PHI, 2013). Understanding the determinants of turnover will help policymakers, agencies, workers, clients, and their families to modify, to the extent possible, specific policy-level, workplace-level, and worker-level factors that will support a more stable, quality home health workforce.

Theoretical Background

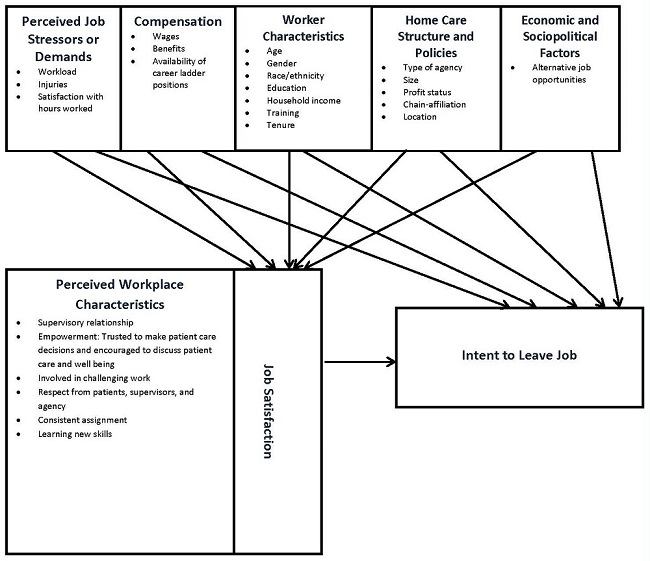

This study adapts the job demand control/support model and social, economic, and geo-political conceptual framework to examine dimensions of the job, agency, worker characteristics, and economic and sociopolitical factors and their impact on job satisfaction and intent to leave the job (Karasek, 1979; Delp, Wallace, Geiger-Brown, & Muntaner, 2010). Figure 1 outlines the model, which conceptualizes influencers on job satisfaction and intent to leave from a multilevel perspective--dyadic care interactions and controls set within home care structure and policies, economic and sociopolitical factors, compensation, and workplace characteristics together influence job satisfaction. The dyadic care relationship encompasses the physical and emotional interaction between workers and consumers, peers and supervisors, and the demands and rewards of that interaction as well as controls. Workplace characteristics include decision latitude and relationship with supervisors and clients. These workplace characteristics may exert direct positive effects on job satisfaction and indirectly positively influence intent to stay. Policies frame the setting within which interactions occur. Policies of interest include compensation, provision of benefits, efforts to prevent injuries, and meeting employees’ preferences for hours. Job stressors and demands, compensation, home care structure and policies, and economic and sociopolitical factors (labor market alternatives) may also directly influence intent to leave the job--or these factors may act through job satisfaction to affect intent to leave.

Findings from several studies have served to provide empirical support for the relationship between the factors identified in the model shown in Figure 1, job satisfaction, and intent to leave.

Worker Characteristics: Most of the studies examining home health workers have found that older workers have greater job satisfaction than their younger peers (McCaughey et al., 2012; Delp et al., 2010; Denton, Zeytinoglu, Davies, & Lian, 2002; Benijamali, Jacoby, & Hagopian, 2014). However, in a study of the consumer-directed model in California, older age was correlated with lower job satisfaction (Kietzman, Benjamin, & Matthias, 2008). The literature indicates that older workers are less likely to intend to leave their jobs and have longer job tenure compared with their younger counterparts (McCaughey et al., 2012; Butler et al., 2013; Butler, Wardamasky, & Brennan-Ing, 2012; Morris, 2009).

Only one study assessed household income in a multivariate model of job satisfaction, where it was found that higher income was correlated with higher job satisfaction (McCaughey et al., 2012). The findings from studies examining household income and its correlation with intent to leave the job and/or turnover have been mixed. A study of former home care workers in Washington State found leavers were wealthier than current home care workers, with one in four leavers having a household income at or above $55,000, compared with only 13 percent of stayers (Banijamali, Jacoby, & Hagopian, 2014). McCaughey and colleagues (2012) also found that home health workers with higher incomes were less likely to intend to leave their jobs. However, Butler and colleagues (2012) did not find a significant effect on household income and termination among home health workers in Maine.

Home Care Structure and Policies: Home health workers’ job satisfaction was found to be lower in for-profit home health agencies (McCaughey et al., 2012). Two studies among nursing home assistants, however, did not find a significant association between overall job satisfaction and nursing home ownership status (for-profit versus not-for-profit) (Decker et al., 2009; Bishop et al., 2009). Study findings also show intention to leave the job and turnover may be greater in for-profit nursing homes and home health agencies (McCaughey et al., 2012; Jobs with a Future Partnership, 2003; Castle & Engberg, 2006; Donoghue & Castle, 2006). Brannon and colleagues found that for-profit nursing homes are associated with high turnover organizations (Brannon, Zinn, Mor, & Davis, 2002). Banazak-Holl and Hines (1996) reported turnover rates were 1.7 times higher in for-profit nursing homes compared to not-for-profit nursing homes.

A meta-analysis found a strong association between advancement opportunity and job satisfaction in nursing homes (Karsh, Booske, & Sainfort, 2005) and a study of nursing homes found a positive relationship between career advancement and job satisfaction (Parsons, Simmons, Penn, & Furlough, 2003). The association between career advancement opportunities and aide turnover or turnover intention is mixed. Career advancement opportunities for nursing assistants and home care workers have been found to be negatively correlated with turnover intentions and positively related to intent to stay on the job (Morris, 2009; Brannon, Barry, Kemper, Schreiner, & Vasey, 2007; Luo, Lin, & Castle, 2011; Parson et al., 2003). However, one study did not find a significant effect between turnover intentions and career ladder positions in home health agencies (McCaughey et al., 2012).

Workplace Characteristics: The direct care worker’s assessment of the quality of the relationship between the supervisor and the aide as well as having supportive leadership have been shown over a large number of studies to be a strong indicator of job satisfaction in nursing home and home care settings (Karantzas et al., 2012; Gerstner & Day, 1997; Decker et al., 2009; Beulow, Winburn, & Hutcherson, 1999; Bishop et al., 2008; McGilton, Hall, Wodchis, & Petroz, 2007; DeLoach & Monroe, 2004; Castle et al., 2006; Dawson, 2007; Parson et al., 2003; Karshe et al., 2005; Bishop, Squillace, Meagher, Anderson, & Wiener, 2009). Research also supports that the perceived quality of the supervisor influences an aide’s intention to stay or leave the job, with aides who have a more positive relationship less likely to intend to leave or actually leave the job (Karantzas et al., 2012; Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhoads, 2002; Bowers, Esmond, & Jacobson, 2003; Stearns & D’Arcy, 2008; Brannon et al., 2007; Choi & Johantgen, 2012; Banazak-Holl & Hines, 1996; Bishop et al., 2008; Mittal et al., 2009; Parson et al., 2003; Barborotta, 2010; Straker et al., 2014). Dill et al. (2012) found the opposite--that nursing assistants who reported a higher degree of supervisor support were less likely to intend to stay on their job.

A positive workplace environment can improve job satisfaction and reduce the turnover intentions of direct care workers. Previous research has found that home health workers and nursing assistants who feel empowered--listened to, involved in decision-making, teamwork, have control over work, and experience autonomy--are more likely to be satisfied with their job and less likely to want to leave the job (Seavey & Marquand, 2011; Karsh et al., 2005; Parsons et al., 2003; Bishop et al., 2009; Denton et al., 2002; Sikorska-Simmons, 2005; Butler et al., 2013). Zhang, Punnett and Gore’s (2014) study showed that nursing assistants’ positive perceptions of their workplace conditions (e.g., coworker support, supervisor support, respect received at work, and decision authority) were negatively correlated with intent to leave the job within the next two years. In fact, nursing assistants who reported four positive features of their working condition were 77 percent less likely to indicate strong intention to leave the job. Providing challenging work and respecting aides for the work they do can also improve job satisfaction and turnover (Bishop et al., 2009; Butler et al., 2012; Bowers et al., 2003). Several studies have found non-significant associations between workplace environment variables and turnover (Wiener et al., 2009; Butler et al., 2013).

Job Stressors or Demands: Increased pay or satisfaction with pay is a strong predictor of job satisfaction or retention and can reduce turnover (Bishop et al., 2009; Decker et al., 2009; Mittal et al., 2009; Ejaz, Noelker, & Menne, 2008; Wiener et al., 2009; Morris, 2009; Jobs with a Partnership, 2003; Butler et al., 2013). Rosen, however, found that pay was not a predictor of turnover intent or turnover (Rosen, Stiehl, Mittal, & Leana, 2011).

Studies have found inconsistent findings on the relationship between benefits or health insurance and direct care worker job satisfaction. Ejaz and colleagues (2008) found a positive relationship between the availability of retirement/pension benefits and health insurance coverage with job satisfaction. They did not find a significant relationship between paid sick time and paid holidays with job satisfaction. However, Bishop and colleagues (2009) reported a positive significant relationship between paid sick time and job satisfaction, but did not find a significant relationship between retirement/pension benefits and health insurance with job satisfaction. Delp and colleagues (2010) also found a positive significant association between health care access and job satisfaction.

The majority of research studies on the correlation between health insurance and turnover among direct care workers find that offering health insurance can reduce turnover and/or turnover intentions (Butler et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2013; Decker et al., 2009; Mittal et al., 2009; Howes, 2005; Rosen et al., 2012; Dill et al., 2012). Other studies have found that health insurance is not related to tenure or turnover intentions, while other benefits, such as paid time off, availability of a pension, paid personal, vacation days, and holidays have a positive effect on job tenure (Wiener et al., 2009; Rosen et al., 2011).

Finally, a balanced workload and sufficient time for tasks contributes to job satisfaction (Seavey & Marquand, 2011; Bishop et al., 2009). In addition, direct care workers who perceive a heavy workload are more likely to intend to leave the job, particularly among those working in nursing homes or assisted living facilities compared to home care workers (Brannon et al., 2007). Higher nurse staff levels can decrease HHA turnover (Butler et al., 2012). Injuries, potential for violence, and threats or verbal and physical abuse contribute to lower job satisfaction and job retention and increase turnover intention (McCaughey et al., 2012; Sherman et al., 2008). Dill and colleagues (2013), on the other hand, found workload was not a significant predictor of actual retention.

FIGURE 1. Conceptual Model: Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political Factors that Shape Care Work and Influence Job Satisfaction and Intent to Leave Job

Methods

The study described in this report draws from the conceptual model and literature review discussed above to test the following hypotheses pertaining to home health worker job satisfaction and intent to leave the job. Specifically, this study examines the extent to which, controlling for demographic, labor market, and agency characteristics:

- Supportive workplace and organizational culture characteristics will be positively correlated with job satisfaction and negatively correlated with intent to leave.

- Compensation (wages and benefits) will be positively correlated with job satisfaction and negatively correlated with intent to leave.

- Job stressors or demands will be negatively correlated with job satisfaction and positively correlated with intent to leave the job.

- Job satisfaction will be negatively correlated with intent to leave the job. The factors that influence intent to leave will differ for workers with high levels of job satisfaction and those with low levels of job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction will be negatively correlated with intent to leave the job. The factors that influence intent to leave will differ for workers with high levels of job satisfaction and those with low levels of job satisfaction.

Data to conduct this study were obtained from the 2007 National Home Health Aide Survey (NHHAS) and the 2007 National Home and Hospice Care Survey (NHHCS). Sponsored by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) and conducted in partnership with the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), the NHHAS was designed to gather information on the frontline--home health workforce employed by licensed or certified home health agencies and hospice providers. Data included demographic characteristics, education and training, experiences with client relations, job characteristics, work environment, recruitment and retention, and job satisfaction.

The NHHAS is a national, two-stage probability survey of home health workers that was conducted as a supplement to the NHHCS, a nationally representative sample survey of Medicare-certified and/or Medicaid-certified or state-licensed home health and hospice agencies (Bercovitz et al., 2010). In the first stage of the sample selection process, a stratified random sample of approximately 15,000 home health and hospice agencies stratified by agency type and metropolitan statistical area (MSA) were identified. These agencies were surveyed as part of the 2007 NHHCS, which was fielded between August 2007 and February 2008, to gather information on home health and hospice agencies’ organizational and patient characteristics, caseload or volume, staffing and management, and the provision of services. A total of 1,036 home agencies completed the NHHCS. Agencies that offered only homemaker services or that only supplied durable medical equipment and services were excluded. Home health workers were sampled from 955 of the 984 eligible agencies who had aides to sample.

In the second stage, between one and six aides employed by the agencies that participated in the NHHCS were selected to participate in the NHHAS. Excluded from this sample were aides that were not directly employed by the agency as well as aides that did not provide assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs). A total of 3,377 home health workers completed the NHHAS. Included in the sample were home health workers, certified nursing assistants, hospice aides (also referred to as certified hospice/palliative nursing assistants), and home care aides/personal care attendants.

Specification of Job Satisfaction and Intent to Leave

Level of job satisfaction was determined on the basis of responses to the NHHAS question: “Overall, how satisfied are you with your job?”, with valid responses consisting of “extremely satisfied”, “somewhat satisfied”, “somewhat dissatisfied”, and “extremely dissatisfied”. The NHHAS collected data on the subgroup of home health workers who had left their jobs during the time that they were selected to participate in the survey and the time that the survey was administered. However, the sample size (fewer than 50 unweighted responses) was too small to include in the data analysis. For this reason a proxy variable, suggestive of workers’ intention to leave their job, was constructed. The variable “Intent to leave” was constructed using responses from two items in the 2007 NHHAS: (1) “Are you currently looking for a different job, either as a HHA or doing something different?”; and (2) “How likely is it that you will be leaving this job in the next year?”. Aides that either responded “yes” to the survey item asking whether they were looking for another job or who indicated that they were “very likely” to leave their job in the coming year were categorized as “intending to leave”. All other workers were categorized as “not intending to leave.”

Specification of Independent Variables

As shown in Table 1, independent variables in job satisfaction and intent to leave models were classified according to the theoretical framework depicted in Figure 1. Of the independent variables identified in this table, the focus of analyses was on those factors that were mutable--under the control of the home health agency or that could be reasonably influenced through public policies. These are referred to throughout this report as “policy” variables. Other variables, including demographic and agency characteristics were included as control variables. Intervening variables were comprised largely of variables related to organizational culture, workplace characteristics, and labor market characteristics, defined in terms of unemployment rates in the state in which the home health worker resided at the time the survey was taken.

Agency Structure and Policy Variables

MSA status of agency was included as a control variable with three categories based on the classification of the county of the agency: metropolitan, micropolitan, or neither. Agency ownership and chain-affiliation were combined to form three categories for agencies: chain-affiliated for-profit, standalone for-profit, and not-for-profit or other. The size of the agency was included as a control variable, with size being defined as the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) nursing employees (registered nurse, licensed practical nurse) and direct care employees and contractors (certified HHA/certified nurse aide [CNA], contract HHA/CNAs, non-certified aides).

Agency policy variables included the consistency of patient assignment, which we hypothesized to be linked to job satisfaction and intent to leave job for both workers and patients. The availability of career ladder positions for aides, an agency-level variable derived from the NHHCS, was included as a policy variable indicating advancement potential for direct care workers.

Perceived Workplace Characteristics

Aides’ perceptions are important intervening variables affecting the link between workforce outcomes (job satisfaction and turnover) and agency policies and practices. These variables are subjective and derived from the NHHAS survey of aides. Aide perception variables are considered to be the product both of agency structure and policies, but also influenced by worker characteristics.

Adequate time for assisting patients with ADLs is included as an indicator of how much time is allotted for home health care visits and is conceptually similar to a measure of the staffing rate in an institutional setting. The variable for sufficient time for ADLs has three levels: more than enough time, enough time, and not enough time. Another important intervening variable is whether or not the aide experienced a work-related injury in the past 12 months, which could be a product of training, supervision, environment, or worker characteristics.

Aides’ relationships with their organizations, supervisors, and patients are expected to be an important factor in both their satisfaction and their intent to leave their jobs. In this analysis we have included three relationship variables with two levels: Aide feels valued by Organization (“Very Much” versus “Somewhat or Not at All”), Aide feels respected by Supervisor (“A Great Deal” versus “Somewhat or Not at All”), and Aide feels respected by patients (“A Great Deal” versus “Somewhat or Not at All”).

Given the frequency of part-time work among home health and hospice aides, two variables were combined to assess aides’ satisfaction with their hours. The number of hours aides worked in a given week was combined with whether aides would like more hours, fewer hours, or think their hours are about right to yield four categories: Part-time (<30 hours/week) & Want More Hours, Full-Time (>30 hours/week) & Want Fewer Hours, Hours About Right, and Other (“PT/wants fewer hours” or “FT/wants more hours”). Most aides (72.0 percent) thought their hours were “about right” and only 14.3 percent indicated that they worked part-time and wanted more hours. Approximately 3.3 percent of aides worked full-time and wanted fewer hours.

Compensation

Pay and benefits are policy variables that are expected to directly influence worker satisfaction and retention. Wages were included in the analysis as a continuous variable. Hourly wages were computed for salaried workers based on self-reported hours and pay amounts. Wage amounts are in 2007 dollars and were not adjusted for inflation or for local differences in cost of living. The mean hourly wage for the analytical sample was $12.15.

While both the agency-level NHHCS and the NHHAS contain data on benefits, prior research has identified discrepancies between agencies’ and aides’ reporting of the availability of benefits (Bishop et al., 2009). Agencies may not supply the same benefits to all workers. Furthermore, aides’ perceptions of their benefits are expected to affect their satisfaction and turnover intentions more than agencies’ reported benefits; therefore, aide-level benefit information from the NHHAS was used in this analysis. Some benefits (paid sick leave, paid holidays, paid personal or vacation days) were eliminated from the analysis because they were not found to significantly affect either dependent variable. The availability of health insurance and the availability of pension or retirement plans were retained in the multivariate analysis.

Worker Characteristics

A number of worker characteristics derived from the NHHAS were included in the analysis as control variables. Aides’ age (<30 years, 30-54 years, and >55 years), race (White only, Black/African-American only, Other), and Hispanic/Latino ethnicity were included. Due to the small number of males in the sample (5.0 percent), gender was not included in the analysis. Aides’ education was limited to three levels: No HS Diploma/GED, Diploma/GED, and some college. Over 40.0 percent of aides reported having some college and only 6.3 percent had neither a diploma nor a GED.

Some variables, such as having ever had formal training and presently working at more than one job concurrently, may be influenced by agency policies (training and hours, respectively). However, these were included primarily as control variables. In addition, several factors mediating the relationship between job satisfaction and workers’ intentions to leave may result in dissatisfied workers staying in their jobs. Factors that influence labor mobility among this demographic of low-wage workers could include household poverty or a household relying on a single income with dependent children. Labor market conditions, represented in this analysis by state unemployment rates, may also discourage aides from leaving their jobs.

Variables described above are presented in Table 1, along with the specification of response categories, population mean for each variable, the source of data for each variable, and the role of each variable in the multivariate model (e.g., policy, control).

TABLE 1. Description of Variables Included in Models of Job Satisfaction and Intent to Leave, NHHAS, 2007

| Variables Included in Model | Response Categories or Levels | Proportion of Respondents (%) | Data Source | Type/Role of Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Job satisfaction | Extremely satisfied | 47.2% | NHHAS | Dependent, Intervening |

| Somewhat satisfied | 38.9% | |||

| Dissatisfied | 13.9% | |||

| Intend to leave job in next 12 months | Yes | 24.2% | NHHAS | Dependent |

| Worker Characteristics | ||||

| Age | <30 | 12.4% | NHHAS | Control |

| 30-54 | 62.8% | |||

| >55 | 24.9% | |||

| Race | White only | 53.9% | NHHAS | Control |

| Black only | 35.2% | |||

| Other | 10.9% | |||

| Hispanic/Latino Ethnicity | Yes | 7.5% | NHHAS | Control |

| Education | <No Diploma or GED | 6.3% | NHHAS | Control |

| HS Diploma or GED | 53.2% | |||

| At least some college | 40.4% | |||

| Household income (% FPL) | <100% FPL | 19.3% | NHHAS, Census Bureau | Control |

| 100-199% FPL | 34.7% | |||

| 200-299% FPL | 27.8% | |||

| >300% FPL | 18.2% | |||

| Received formal training | Yes | 84.7% | NHHAS | Control |

| Aide only worker in household with dependent children | Yes | 17.0% | NHHAS | Control |

| Holds more than 1 job | Yes | 22.3% | NHHAS | Control |

| Home Care Structure& Policies | ||||

| MSA status of agency | Metropolitan | 82.9% | NHHCS | Control |

| Micropolitan | 11.5% | |||

| Neither | 5.6% | |||

| Ownership and chain- affiliation of agency | Chain-affiliated for-profit | 25.1% | NHHCS | Control |

| Standalone for-profit | 32.4% | |||

| Not-for-profit/other | 42.5% | |||

| Assignment of patients each week | Same patients | 82.5% | NHHAS | Policy |

| Patients change | 8.6% | |||

| Combination | 8.8% | |||

| Job & Workplace Characteristics | ||||

| Aide feels valued by organization | Very much | 67.6% | NHHAS | Intervening |

| Somewhat /not at all | 32.3% | |||

| Worker feels respected by patients | A great deal | 91.2% | NHHAS | Intervening |

| Somewhat/not at all | 8.8% | |||

| Worker feels respected by supervisor | A great deal | 76.7% | NHHAS | Intervening |

| Somewhat/not at all | 23.2% | |||

| Satisfaction with hours worked and FT status | PT, want more hours | 14.3% | NHHAS | Intervening |

| PT wants fewer hours/ FT wants more hours | 10.1% | |||

| FT, fewer hours | 3.3% | |||

| Hours about right | 72.3% | |||

| Adequate time to assist patients with ADLs | More than enough time | 42.3% | NHHAS | Intervening |

| Enough time | 53.6% | |||

| Not enough time | 4.1% | |||

| Has had work-related injury in past 12 months | Yes | 12.9% | NHHAS | Intervening |

| Compensation | ||||

| Hourly wage | Dollars per hour (2007) | $12.15 | NHHAS | Policy |

| Career ladder positions are available at agency | Yes | 9.8% | NHHCS | Policy |

| Receives paid sick leave | Yes | 57.4% | NHHAS | Policy |

| Receives paid time off | Yes | 66.5% | NHHAS | Policy |

| Health insurance available | Yes | 77.0% | NHHAS | Policy |

| Pension or retirement plan available | Yes | 54.6% | NHHAS | Policy |

| Don't know | 7.1% | |||

| No | 38.3% | |||

| Economic & Sociopolitical Factors | ||||

| State unemployment rate, 2007 | 4.7% | BLS | Control | |

Analytical Approach

An analytic file was prepared by merging data from the NHHAS and NHHCS using agency identifiers. Due to the confidential nature of selected data elements (e.g., CMS provider numbers) and the need to access non-publicly available data, the merge was performed by the NCHS Research Data Center. Following this merge, a de-identified, aide-level file was made available for use in this study. All analyses were conducted with weighted samples, using a with-replacement design approach. The NHHAS represents a weighted population of 160,720 home health workers. Accounting for missing or anomalous data needed to perform these analyses, a total of 119,500 weighted cases, were included in this study. Compared to cases excluded due to missing data, the sample included in the analysis is not statistically different in terms of job satisfaction or intent to leave job; however, they are more likely to work for a non-profit agency, to hold only one job, to work full-time, to have a pension/retirement, and to receive paid time off (sick leave, personal days, and holidays). Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the 119,500 weighted cases included in the analysis for a subset of variables.

Bivariate analyses, consisting primarily of frequencies, means, and corresponding tests of significance, chi-square and t-tests, respectively, were conducted to understand how home health worker subgroups--defined by level of job satisfaction and intent to leave their job--differed in terms of the characteristics of the aide, agency, work environment, and organizational culture. These results are summarized in Table 2. Data were analyzed with SAS-callable SUDAAN to account for the NHHAS complex survey design. Chi-square tests and t-tests were performed to determine whether differences in subgroups were statistically significant at the p<0.05 level.

Multivariate Analyses of Job Satisfaction: The Multilog procedure in SAS-callable SUDAAN was used to estimate the multinomial logistic regression models. Multinomial logistic regression, which assumes that the dependent variable is nominal, was used to assess the determinants of job satisfaction among home health workers.1 “Extremely satisfied” is compared to “dissatisfied” and “somewhat satisfied” to “dissatisfied” for the analytical sample of 119,500 weighted cases. Coefficients obtained from the multinomial logistic regression are interpreted as the effect of the independent variable on the log-odds of being in one category as opposed to the base category or reference group. Job satisfaction was coded as three levels. For the purpose of this analysis, “dissatisfied” respondents were identified as the reference group.

Multivariate Analyses of Intent to Leave

Intent to leave, a dichotomous dependent variable (yes/no) was modeled using a logistic regression approach. Two different analytical populations were studied: the whole analytical sample of 119,500 aides, and a subset of 63,070 aides who were not extremely satisfied. While only 53 percent of the sample, this population of aides nonetheless accounts for roughly 85 percent of workers who intend to leave their jobs. Subpopx in SAS-callable SUDAAN was used to ensure that weights were applied correctly. Due to the limited number of intended leavers among the aides who were “extremely satisfied”, multivariate analysis for that population could not be reliably estimated.

Two alternative modeling approaches of intent to leave were included for a number of reasons. First, we had an a priori expectation that the factors that drive intent to leave are likely to differ for those workers who are satisfied with their jobs and those workers who are dissatisfied with their jobs. Second, the key independent variable in the intent-to-leave model--job satisfaction--was expected to be influenced by workers’ personality traits (e.g., attitudes and background) that are not directly observable. Such a model would be affected by omitted variable bias. However, the whole population approach was included for its policy relevance: agencies that wish to retain aides would find it difficult to identify workers with higher and lower satisfaction and to apply different approaches to them.

A two-stage model was not included due to the difficulty of constructing an instrumental variable that is highly correlated with job satisfaction. As we discovered in conducting multivariate analyses of job satisfaction, independent variables in these models were generally found to have poor predictive power.

1 Job satisfaction was initially modeled using ordered multinomial logit regression. This model assumes a common slope with separate intercepts for each level of the dependent variable. The ordered model failed to meet the proportional odds assumptions, and job satisfaction was subsequently modeled using a nominal model.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

The NHHAS represented a weighted total of 160,720 home health workers. Following the exclusion of cases with missing or anomalous values for variables required to conduct analyses, a weighted total of 119,500 aides--nearly 75 percent of the original population--were available for inclusion in this study. In order to determine the extent to which the study sample differed from the full sample in key characteristics, bivariate analyses with corresponding t-tests and chi-square were estimated to determine whether differences in aide, agency, and job characteristics, as well as satisfaction and intent to leave, were statistically significant at the 5 percent level. None of the comparisons between the full and study population were found to be statistically different, suggesting that the study population was suitably representative of the full population of home health workers for the variables included.

As shown in Table 1, across the study population approximately 47.2 percent of workers reported that they were extremely satisfied, 38.9 percent reported that they were somewhat satisfied, and 13.9 percent reported being dissatisfied with their job. Slightly less than one in four home health workers reported their intent to leave their job in the coming year. Approximately 67 percent of workers who were dissatisfied expressed the intention to leave their job compared to 8 percent of those that were extremely satisfied with their job.

As shown in Table 1, nearly two-thirds of home health workers in the study sample were between the ages of 30 and 54. Subgroups of workers, distinguished by level of job satisfaction (Table 2), did not differ in age distribution. However, a larger proportion of intended stayers (27.6 percent) than intended leavers (16.2 percent) were aged 55 or older. Subgroups differing by level of job satisfaction and intent to leave job did not differ significantly on other aide characteristics that included race, Hispanic ethnicity, and type of aide (e.g., CNA, home care aide, hospice aide).

Descriptive analyses indicated that job satisfaction was not associated with type of agency although the proportion of leavers and stayers did differ by agency type. Approximately 34.6 percent of intended leavers were employed in a for-profit chain, compared to only 22.0 percent of intended stayers. Agency location was found to be associated with both job satisfaction and intent to leave. Among those that were extremely satisfied with their job, 81.6 percent were employed by an agency located in a metropolitan area compared to 91.2 percent of those that were dissatisfied with their job. Similarly, a greater proportion of intended leavers were employed by a metropolitan-based agency. Other agency characteristics, including size and availability of career ladder positions, were not associated with job satisfaction or intent to leave.

Overall, the hourly wage for this sample of home health workers averaged $12.15. Mean wage was not statistically different across subgroups of workers that differed by level of job satisfaction or intent to leave. Nonetheless, some benefits were associated with satisfaction and intent to leave. Workers who were extremely satisfied and those who intended to stay on the job were substantially more likely to be offered paid sick days and pensions compared to those who were dissatisfied and those that intended to leave their job. Across the study population, approximately 77.0 percent of workers were offered health insurance through the workplace. Workers that differed by level of job satisfaction did not significantly differ in the proportion that was offered health insurance. Compared to intended stayers, however, intended leavers were less likely to be offered health insurance (63.6 percent versus 81.2 percent).

Nearly 70 percent of all home health workers represented in the analysis worked full-time, defined as 30 or more hours per week. A greater proportion of intended stayers than intended leavers worked full-time (73.5 percent versus 57.9 percent).

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Population in Study Sample by Job Satisfaction and Intent to Leave Job, NHHAS, 2007

| Job Satisfaction | Intent to Leave | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely Satisfied | Somewhat Satisfied | Dissatisfied | Intended Leavers | Intended Stayers | ||||

| Population | Weighted N | 56,430 | 46,476 | 165,94 | 28,940 | 90,560 | ||

| Percent sample | Percent (%) | 47% | 39% | 14% | 24% | 76% | ||

| Distribution (%) and P-Values | ||||||||

| Percent | Percent | Percent | P-Value | Percent | Percent | P-Value | ||

| Job Satisfaction & Intent to Leave Job | ||||||||

| Job satisfaction | Extremely | 15.6 | 57.6 | <0.01 | ||||

| Somewhat | 45.8 | 36.4 | ||||||

| Dissatisfied | 38.5 | 5.9 | ||||||

| Intend to leave job | Yes | 8 | 29 | 67 | <0.01 | |||

| Worker Characteristics | ||||||||

| Age (years) | <30 | 9.4 | 15.2 | 14.4 | 0.17 | 18.2 | 10.4 | 0.05 |

| 30-54 | 60.5 | 64.6 | 65.1 | 65.5 | 61.8 | |||

| >55 | 30.0 | 20.1 | 20.4 | 16.2 | 27.6 | |||

| Race | White only | 58.8 | 48.6 | 51.4 | 0.45 | 46.8 | 56.1 | 0.29 |

| Black only | 29.6 | 41.0 | 37.8 | 43.6 | 32.5 | |||

| Other | 11.5 | 10.3 | 10.7 | 9.5 | 11.3 | |||

| Hispanic | Yes | 7.4 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 0.96 | 6.2 | 7.9 | 0.51 |

| Aide household's poverty status | <100% FPL | 16.6 | 19.5 | 27.6 | 0.84 | 28.1 | 16.4 | 0.19 |

| 100-199% FPL | 33.6 | 35.9 | 34.9 | 28.5 | 36.7 | |||

| 200-299% FPL | 30.9 | 24.7 | 25.5 | 21.9 | 29.6 | |||

| Above 300% FPL | 18.7 | 19.7 | 11.8 | 21.3 | 17.1 | |||

| Aide has more than 1 job | Yes | 20.3 | 22.9 | 27.5 | 0.77 | 23.9 | 21.8 | 0.72 |

| Education | <HS | 4.9 | 6.4 | 11.7 | 0.19 | 4.8 | 6.9 | 0.46 |

| HS Grad or GED | 59.3 | 47.6 | 47.0 | 49.5 | 54.3 | |||

| At least some college | 35.6 | 45.9 | 41.2 | 45.6 | 38.7 | |||

| Aide only worker in household with dependent children | Yes | 14.2 | 21.6 | 13.3 | 0.25 | 18.5 | 16.5 | 0.68 |

| Agency Structure & Policies | ||||||||

| Type of ownership of agency | Chain, for-profit | 21.4 | 31.3 | 20.0 | 0.06 | 34.6 | 22.0 | <0.01 |

| Standalone for-profit | 30.9 | 26.7 | 52.9 | 38.5 | 30.4 | |||

| Not-for-profit | 47.6 | 41.8 | 26.9 | 26.7 | 47.5 | |||

| Location of agency | Metropolitan | 81.6 | 81.3 | 91.2 | 0.03 | 86.0 | 81.8 | <0.01 |

| Micropolitan | 11.0 | 14.4 | 4.7 | 10.3 | 11.8 | |||

| Neither | 7.3 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 6.3 | |||

| Size of Agency | Mean FTE nursing and direct care staff | 54.7 | 56.0 | 64.3 | 0.44 | 60.8 | 55.2 | 0.43 |

| Assignment | Same patients | 83.3 | 81.0 | 83.9 | 0.52 | 77.4 | 84.1 | 0.32 |

| of patients | Patients change | 6.7 | 11.2 | 8.2 | 12.1 | 7.5 | ||

| each week | Combination | 9.9 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 10.4 | 8.2 | ||

| Aide encouraged by agency to talk with patient's family | Yes | 62.2 | 52.1 | 39.4 | 0.03 | 49.0 | 57.1 | 0.19 |

| Compensation | ||||||||

| Mean hourly wage (2007) | $/hour | $11.73 | $12.26 | $13.27 | 0.42 | $12.68 | $11.98 | 0.49 |

| Health insurance | Yes | 83.1 | 72.5 | 68.4 | 0.90 | 63.6 | 81.2 | <0.01 |

| Pension or retirement plan | Yes | 61.9 | 55.6 | 26.7 | 0.01 | 39.3 | 59.3 | 0.01 |

| No | 30.9 | 37.7 | 65.0 | 54.6 | 33.1 | |||

| Don't know | 7.1 | 6.6 | 8.2 | 6.0 | 7.5 | |||

| Personal days | Yes | 73.8 | 62.6 | 52.1 | 0.07 | 61.0 | 68.2 | 0.25 |

| Sick days | Yes | 68.5 | 51.4 | 36.3 | <0.01 | 45.3 | 61.3 | 0.01 |

| Paid holidays | Yes | 66.9 | 49.3 | 46.1 | <0.01 | 52.2 | 58.8 | 0.29 |

| Availability of career ladder positions | Yes | 7.8 | 10.3 | 14.8 | 0.41 | 11.1 | 9.3 | 0.37 |

| Job & Workplace Characteristics | ||||||||

| Hours worked per week | Mean | 33.0 | 32.0 | 30.4 | 0.43 | 28.6 | 33.4 | <0.01 |

| Works FT | >30 hours | 73.0 | 69.8 | 57.3 | 0.28 | 57.9 | 73.5 | 0.01 |

| Received formal training | Yes | 87.5 | 85.0 | 74.6 | 0.22 | 78.9 | 86.5 | 0.09 |

| On-the-job injury in past 12 months | Yes | 9.3 | 15.6 | 17.5 | 0.11 | 18.7 | 11.0 | 0.10 |

| Satisfaction with hours and FT (>30 hours per week) | PT, want more hours | 9.3 | 17.2 | 22.7 | 0.06 | 26.9 | 10.3 | <0.01 |

| PT/wants fewer Hours OR FT/wants more hours | 10.4 | 10.0 | 9.1 | 5.1 | 11.6 | |||

| FT, fewer hours | 0.9 | 2.7 | 13.0 | 6.3 | 2.3 | |||

| Hours about right | 79.3 | 69.9 | 55.0 | 61.5 | 75.6 | |||

| Adequacy of time to assist patients with ADLs | More than enough time | 45.0 | 41.9 | 33.4 | 0.29 | 39.2 | 43.2 | 0.06 |

| Enough time | 52.7 | 54.0 | 55.3 | 50.5 | 54.6 | |||

| Not enough time | 2.1 | 4.0 | 11.2 | 10.2 | 2.1 | |||

| Aide feels respected by supervisor as part of the health care team | A great deal | 92.9 | 67.2 | 47.9 | <0.01 | 64.9 | 80.4 | <0.01 |

| Somewhat or not at all | 7.0 | 32.7 | 52.0 | 35.0 | 19.4 | |||

| Aide feels organization values their work | A great deal | 89.4 | 52.4 | 35.9 | <0.01 | 47.4 | 74.0 | <0.01 |

| Somewhat or not at all | 10.6 | 47.5 | 63.9 | 52.5 | 25.8 | |||

| Aide feels respected by patients as part of the health care team | A great deal | 93.1 | 89.3 | 89.9 | 0.39 | 88.2 | 92.1 | 0.22 |

| Somewhat/not at all | 6.8 | 10.6 | 10.0 | 11.7 | 7.8 | |||

| Aide feels involved in challenging work | Strongly agree | 83.5 | 57.3 | 50.8 | <0.01 | 56.1 | 72.8 | <0.01 |

| Somewhat agree | 13.2 | 33.2 | 15.5 | 20.9 | 21.4 | |||

| Somewhat/strongly disagree | 3.1 | 9.3 | 33.6 | 22.9 | 5.6 | |||

| Aide feels trusted with patient care decisions | Strongly agree | 86.9 | 69.8 | 68.4 | <0.01 | 68.4 | 80.7 | 0.03 |

| Somewhat agree | 10.6 | 24.2 | 9.4 | 15.9 | 15.6 | |||

| Somewhat/strongly disagree | 2.3 | 6.0 | 22.1 | 15.6 | 3.6 | |||

Multivariate Analyses: Job Satisfaction

Results of the multinomial logistic regression based on a weighted sample of 119,500 aides in the analytical sample are presented in Table 3. This analysis tests two models: model I excludes variables based on worker perceptions that were suspected to be endogenous with job satisfaction (HHA feels valued by organization, Aide feels involved in challenging work, Aide feels trusted with patient care decisions, Aide feels confident in ability to do job, Time for ADLs, Satisfaction with hours, Aide feels respected by supervisor, Aide feels respected by patients), while model II includes these variables.

For each model, the effect of independent variables on the odds of being extremely satisfied versus dissatisfied, and the effect of independent variables on the odds of being somewhat satisfied versus dissatisfied are estimated. As shown in Table 2, job satisfaction was associated with worker characteristics, home care structure and policies, perceived workplace characteristics and perceived job stressors.

Worker Characteristics: Neither age nor race or Hispanic/Latino ethnicity were found to be associated with job satisfaction after other factors were accounted for. In model II, workers lacking a High School Diploma or a GED were found to have significantly lower satisfaction than workers with some college or higher, and being the only worker in a household with dependent children was associated with higher odds of being somewhat satisfied versus dissatisfied in model II. Household poverty status was not associated with job satisfaction in either model. Having received formal training was associated with higher satisfaction, though the odds ratio was not statistically significant for model II (extremely satisfied versus dissatisfied).

Perceived Workplace Characteristics: The odds of being satisfied with one’s job were significantly associated with a worker’s feeling of being respected by one’s supervisor and valued by one’s organization after other factors were accounted for. Perceptions of being involved in challenging work were significantly associated with higher job satisfaction, although the odds of being extremely satisfied with one’s job were higher among those that “somewhat agreed” (OR=16.79) compared to those that “strongly agreed” (OR=9.36) that their work was challenging. Being trusted to make patient care decisions and feeling respected by patients were not significantly associated with job satisfaction.

Compensation: After other factors were accounted for, hourly wage was inversely associated with satisfaction in model II, with the odds of being extremely satisfied lower for those with higher wages. Also important for job satisfaction was having a pension or retirement plan available. Interestingly, not knowing if a pension or retirement plan was available was significantly correlated with higher satisfaction, but only for the model II. Having health insurance was not associated with satisfaction, nor was paid sick leave, paid holidays, paid personal or vacation time available, or reporting a pay raise in the past year (not presented). Workers in agencies that reported having career ladder positions for aides, a form of advancement potential, were found to have significantly lower odds of being extremely satisfied versus dissatisfied.

Job Stressors or Demands: Workers who experienced an on-the-job injury in the past 12 months were found to have significantly lower odds of being extremely satisfied in model I, but not in model II. In model II, aides who report working full-time and wanting fewer hours had greatly reduced odds of being extremely or somewhat satisfied (0.04 and 0.08, respectively) than those who reported their hours were “about right.” Working more than one job and time for assisting patients with ADLs were not correlated with satisfaction.

Agency Structure and Policies: Workers who report being encouraged by their agencies to discuss patient care with family have significantly higher odds of being extremely satisfied in both models. Agency ownership was also associated with satisfaction. Aides in standalone for-profit agencies report significantly lower satisfaction than those in not-for-profit agencies, though the odds ratio is not significant for model I extremely satisfied versus not extremely satisfied. Aides working for agencies located in counties classified as “Neither” (i.e., rural) or “Micropolitan” had higher odds of being satisfied, but the odds ratios did not achieve statistical significance.

Economic and Sociopolitical Factors: State unemployment rates were negatively correlated with the odds of being somewhat satisfied versus dissatisfied in model I only.

TABLE 3. Multivariate Analysis of Job Satisfaction

| Model I | Model II | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely Satisfied vs. Dissatisfied (OR) | Somewhat Satisfied vs. Dissatisfied (OR) | Extremely Satisfied vs. Dissatisfied (OR) | Somewhat Satisfied vs. Dissatisfied (OR) | ||

| Intercept | 4.75 (0.23-99.88) | 15.14 (0.72-318.6) | 0.01* (0-0.35) | 0.42 (0.01-27.05) | |

| On-the-job injury in past 12 months | Yes | 0.32* (0.13-0.80) | 0.79 (0.29-2.16) | 0.58 (0.19-1.76) | 1.29 (0.45-3.68) |

| Aide encouraged by agency to talk with patient's family | Yes | 2.88* (1.57-5.30) | 1.72 (0.96-3.05) | 2.37* (1.08-5.21) | 1.34 (0.66-2.76) |

| Consistency of patient assignment | Same patients (REF=combination) | 1.77 (0.34-9.26) | 1.79 (0.35-9.11) | 1.69 (0.48-5.97) | 1.56 (0.49-4.91) |

| Patients change (REF=combination) | 1.1 (0.16-7.55) | 1.73 (0.28-10.74) | 1.37 (0.20-9.52) | 1.61 (0.30-8.72) | |

| Received formal training | Yes | 3.18* (1.23-8.22) | 2.64* (1.14-6.14) | 1.89 (0.75-4.78) | 2.52* (1.03-6.19) |

| Career ladder positions available in agency for aides | Yes | 0.30* (0.11-0.85) | 0.41 (0.13-1.33) | 0.20* (0.06-0.64) | 0.37 (0.11-1.28) |

| Health insurance offered at agency | Yes | 0.90 (0.27-2.97) | 0.40 (0.13-1.29) | 1.01 (0.22-4.51) | 0.41 (0.11-1.61) |

| Pension or retirement plan available at agency | Yes (REF=No) | 4.74* (1.77-12.74) | 4.22* (1.49-11.94) | 4.97* (1.43-17.26) | 4.64* (1.48-14.52) |

| Don't know (REF=No) | 3.20 (0.67-15.41) | 3.50 (0.73-16.80) | 11.70* (1.48-92.23) | 8.08* (1.10-59.33) | |

| HHA feels valued by organization | Very much (REF=Somewhat/ not at all) | 10.37* (4.42-24.32) | 1.99 (0.81-4.90) | ||

| Aide feels involved in challenging work | Strongly agree (REF=Somewhat/ strongly disagree) | 9.36* (3.24-27.07) | 4.89* (1.86-12.88) | ||

| Somewhat agree (REF=Somewhat/ strongly disagree) | 16.79* (4.65-60.69) | 18.08* (5.60-58.37) | |||

| Aide feels trusted with patient care decisions | Strongly agree (REF=Somewhat/ strongly disagree) | 2.61 (0.68-10.02) | 1.36 (0.40-4.64) | ||

| Somewhat agree (REF=Somewhat/ strongly disagree) | 5.62* (1.02-31.07) | 5.76* (1.32-25.18) | |||

| Aide feels confident in ability to do job | Strongly agree (REF=Somewhat/ strongly disagree) | 1.39 (0.41-4.71) | 1.58 (0.53-4.68) | ||

| Somewhat agree (REF=Somewhat/ strongly disagree) | 1.18 (0.21-6.60) | 1.68 (0.41-6.81) | |||

| Time for ADLs | More than enough time (REF=Enough time) | 1.38 (0.40-4.71) | 1.62 (0.52-5.11) | ||

| Not enough time (REF=Enough time) | 0.35 (0.07-1.90) | 0.38 (0.12-1.22) | |||

| Satisfaction with hours | PT, want more hours (REF=Hours about right) | 0.65 (0.19-2.19) | 1.29 (0.43-3.84) | ||

| PT/fewer hours OR FT/more hours (REF=Hours about right) | 0.59 (0.24-1.46) | 0.56 (0.22-1.40) | |||

| FT, fewer hours (REF=Hours about right) | 0.04* (0.01-0.17) | 0.08* (0.02-0.33) | |||

| Aide feels respected by supervisor | A great deal (REF=Somewhat or not at all) | 16.52* (6.00-45.53) | 3.94* (0.02-0.33) | ||

| Aide feels respected by patients | A great deal (REF=Somewhat or not at all) | 0.90 (0.25-3.18) | 0.91 (0.26-3.20) | ||

| Aide's poverty status | <100% FPL (REF=Over 300% FPL) | 0.47 (0.12-1.83) | 0.44 (0.11-1.72) | 0.31 (0.07-1.28) | 0.39 (0.11-1.36) |

| 100-199% FPL (REF=Over 300% FPL) | 0.56 (0.17-1.80) | 0.50 (0.16-1.63) | 0.47 (0.18-1.18) | 0.41 (0.16-1.05) | |

| 200-299% FPL (Ref=Over >300% FPL) | 0.92 (0.31-2.77) | 0.64 (0.21-1.97) | 0.78 (0.26-2.34) | 0.49 (0.18-1.34) | |

| Only worker with dependent children | Yes | 1.30 (0.38-4.45) | 2.07 (0.61-7.03) | 3.78 (0.98-14.54) | 5.19* (1.58-17.05) |

| Education | No diploma/GED (REF=Some college) | 0.30 (0.06-1.53) | 0.31 (0.07-1.43) | 0.08* (0.01-0.45) | 0.13* (0.02-0.71) |

| HS Grad or GED (REF=Some college) | 1.64 (0.74-3.68) | 0.89 (0.41-1.92) | 1.00 (0.36-2.80) | 0.58 (0.22-1.53) | |

| Ownership of agency | Chain-affiliated for- profit (REF=Not-for- profit/other) | 0.72 (0.28-1.83) | 1.00 (0.36-2.73) | 1.56 (0.56-4.35) | 2.01 (0.70-5.81) |

| Standalone for- profit (REF=Not-for- profit/other) | 0.42 (0.17-1.09) | 0.29* (0.10-0.82) | 0.38* (0.16-0.90) | 0.26* (0.10-0.66) | |

| Aide works more than 1 job | Yes | 0.69 (0.27-1.73) | 0.60 (0.26-1.41) | 0.92 (0.38-2.23) | 0.68 (0.30-1.52) |

| Age | <30 (REF=55 and over) | 0.61 (0.19-1.94) | 1.00 (0.32-3.13) | 0.36 (0.11-1.22) | 0.67 (0.22-2.11) |

| 30-54 (REF=55 and over) | 0.72 (0.35-1.47) | 0.81 (0.34-1.92) | 0.71 (0.27-1.85) | 0.63 (0.24-1.67) | |

| Race | Other (REF=White only) | 1.93 (0.50-7.52) | 1.41 (0.42-4.81) | 2.15 (0.60-7.76) | 2.28 (0.72-7.20) |

| Black/African- American only (REF=White Only) | 1.13 (0.46-2.76) | 1.91 (0.90-4.05) | 0.61 (0.25-1.50) | 1.44 (0.66-3.13) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | Yes | 1.32 (0.29-6.08) | 1.53 (0.36-6.46) | 1.90 (0.55-6.59) | 1.94 (0.61-6.15) |

| MSA status of agency | Neither (REF=Metropolitan) | 1.85 (0.34-10.04) | 1.17 (0.21-6.41) | 2.83 (0.97-8.27) | 2.00 (0.66-6.10) |

| Micropolitan (REF=Metropolitan) | 2.97 (0.92-9.60) | 4.83 (1.43-16.37) | 1.71 (0.38-7.79) | 3.59 (0.75-17.11) | |

| Computed hourly wage | 0.95 (0.89-1.02) | 0.99 (0.93-1.06) | 0.92* (0.85-0.99) | 0.97 (0.90-1.03) | |

| State unemployment rate, 2007 | 0.75 (0.50-1.13) | 0.64* (0.43-0.94) | 1.05 (0.73-1.53) | 0.80 (0.54-1.18) | |

Multivariate Analyses: Intent to Leave

Table 4 presents four models for intent to leave. The models differ in populations included and in the variables they contained. Models I, II, and III include all 119,500 weighted cases in the analytical sample. Model IV includes a smaller subset of the population, the 63,070 weighted cases that identify themselves as “somewhat satisfied” or “dissatisfied” with their job. Some variables in model IV had to be dropped due to small sample sizes for some levels among the not “extremely satisfied” population.

Job Satisfaction: Job satisfaction is strongly correlated with intention to leave even after controlling for worker characteristics, compensation, perceived workplace characteristics, job stressors and demands, and agency characteristics and policies in model II.

Worker Characteristics: Among aide characteristics, only household poverty status, age, and race are significantly correlated with intent to leave job. Aides with race of Black/African-American only have more than twice the odds of White only aides to intend to leave their jobs; however, among aides who are not extremely satisfied, the odds ratio does not achieve statistical significance. Workers below the age of 30 have higher odds of intending to leave, but only in model III, which excludes job satisfaction, is the result significant. Aides who have an income of 100-199 percent or 200-299 percent of the FPL are significantly less likely to intend to leave their jobs than households with incomes over 300 percent FPL.

Compensation: In model II, when controlling for job satisfaction, health insurance is correlated with lower intent to leave. In model III, when job satisfaction is excluded, workers in agencies with career ladder positions report significantly higher turnover intentions. Having a pension or retirement plan available did not affect intent to leave nor did wage levels.

Perceived Workplace Characteristics: In model III, which excludes job satisfaction, aides who reported feeling valued by their organizations and respected by their supervisors all had lower intention to leave. Working part-time and wanting more hours was significantly correlated with higher intent to leave compared to reporting “hours about right”. Either working part-time and wanting fewer hours or full-time and wanting more was associated with lower intention to leave. Having a consistent patient assignment was significantly associated with lower turnover intentions.

Job Stressors or Demands: Having had an injury in the past six months was consistently associated with higher intention to leave. In model III, which excludes job satisfaction, aides who reported having enough time for ADLs had lower intention to leave. Working more than one job was not correlated with intent to leave.

Agency Structures and Policies: Workers in for-profit chain-owned agencies are more than twice as likely to intend to leave their jobs as those in non-profit/other agencies; however, the odds ratio is not significant for the "not extremely satisfied" population (model IV). Reporting being encouraged to discuss patient care with patients’ families and the MSA status of an agency’s county were not significant.

Economic and Sociopolitical Factors: State unemployment rates were associated with higher intent to leave among aides who were not extremely satisfied (model IV), but were otherwise insignificant.

TABLE 4. Intent to Leave Logistic Regression Model

| Model I Entire Sample (OR) | Model II Entire Sample (OR) | Model III Entire Sample (OR) | Model IV Not "Extremely Satisfied" (OR) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted N: | 119,500 | 119,500 | 119,500 | 63,070 | |

| Intercept | 2.05* (1.11-3.79) | 20.21* (1.85-220.49) | 9.99 (0.94-106.27) | 1.08 (0.10-11.26) | |

| Job satisfaction | Satisfied (REF=Dissatisfied) | 0.04* (0.02-0.09) | 0.05* (0.02-0.13) | ||

| Somewhat satisfied (REF=Dissatisfied) | 0.20* (0.10-0.39) | 0.16* (0.08-0.31) | |||

| On-the-job injury in past 12 months | Yes | 2.41* (1.31-4.43) | 2.44* (1.32-4.50) | 2.85* (1.35-6.06) | |

| Aide encouraged by agency to talk with patient's family | Yes | 1.22 (0.70-2.14) | 1.05 (0.60-1.83) | 1.15 (0.60-2.23) | |

| Consistency of patient assignment | Same patients (REF=combination) | 0.24* (0.11-0.50) | 0.26* (0.12-0.56) | 0.15* (0.05-0.47) | |

| Patients change (REF=combination) | 0.52 (0.21-1.30) | 0.57 (0.21-1.53) | 0.44 (0.12-1.70) | ||

| Received formal training | Yes | 0.83 (0.34-1.99) | 0.75 (0.34-1.69) | 0.47 (0.21-1.08) | |

| Career ladder positions available in agency for aides | Yes | 1.41 (0.77-2.58) | 1.91* (1.06-3.45) | 1.49 (0.69-3.21) | |

| Health insurance offered at agency | Yes | 0.45* (0.23-0.87) | 0.55 (0.25-1.20) | 0.74 (0.33-1.69) | |

| Pension or retirement plan available at agency | Yes (REF=No) | 1.02 (0.53-1.96) | 0.68 (0.34-1.37) | 0.6 (0.26-1.36) | |

| Don't know (REF=No) | 0.89 (0.25-3.24) | 0.50 (0.10-2.43) | 0.33 (0.06-1.78) | ||

| HHA feels valued by organization | Very much (REF=Somewhat/ not at all) | 0.54 (0.26-1.13) | 0.34* (0.18-0.67) | ||

| Aide feels involved in challenging work | Strongly agree (REF=Somewhat/ strongly disagree) | 0.62 (0.22-1.76) | 0.37 (0.14-1.01) | ||

| Somewhat agree (REF=Somewhat/ strongly disagree) | 0.61 (0.19-1.94) | 0.35* (0.12-0.98) | |||

| Aide feels trusted with patient care decisions | Strongly agree (REF=Somewhat/ strongly disagree) | 0.52 (0.13-2.03) | 0.42 (0.12-1.50) | ||

| Somewhat agree (REF= REF=Somewhat/ strongly disagree) | 0.47 (0.11-1.99) | 0.35 (0.08-1.46) | |||

| Time for ADLs | More than enough time (REF=Enough time) | 0.95 (0.52-1.73) | 0.89 (0.46-1.72) | ||

| Not enough time (REF=Enough time) | 3.30 (0.88-12.36) | 3.26* (1.18-8.98) | |||

| Satisfaction with hours | PT, want more hours (REF=Hours about right) | 2.57* (1.13-5.85) | 2.36* (1.03-5.44) | 2.23 (0.81-6.18) | |

| PT/fewer hours OR FT/more hours (REF=Hours about right) | 0.36* (0.14-0.92) | 0.45* (0.21-0.99) | 0.37* (0.14-0.94) | ||

| FT, fewer hours (REF=Hours about right) | 1.00 (0.30-3.36) | 2.52 (0.70-9.05) | 1.46 (0.36-5.88) | ||

| Aide feels respected by supervisor | A great deal (REF=Somewhat or not at all) | 1.42 (0.68-2.98) | 0.86 (0.40-1.84) | 0.69 (0.36-1.34) | |

| Aide feels respected by patients | A great deal (REF=Somewhat or not at all) | 0.85 (0.42-1.72) | 0.89 (0.44-1.79) | 0.65 (0.30-1.39) | |

| Aide's poverty status | <100% FPL (REF=Over 300% FPL) | 0.77 (0.36-1.65) | 0.98 (0.44-2.19) | 1.46 (0.52-4.08) | |

| 100-199% FPL (REF=Over 300% FPL) | 0.34* (0.16-0.73) | 0.41* (0.21-0.83) | 0.43* (0.20-0.91) | ||

| 200-299% FPL (REF=Over 300% FPL) | 0.38* (0.17-0.87) | 0.42* (0.19-0.95) | 0.48 (0.18-1.24) | ||

| Aide the only worker in a household with dependent children | Yes | 0.71 (0.34-1.51) | 0.59 (0.27-1.27) | 0.66 (0.27-1.64) | |

| Education | <HS/GED (REF=Some college) | 0.54 (0.18-1.68) | 1.12 (0.42-2.99) | 0.48 (0.15-1.52) | |

| HS Grad or GED (REF=Some college) | 0.93 (0.49-1.77) | 0.94 (0.47-1.88) | 0.87 (0.44-1.75) | ||

| Ownership | Chain-affiliated for-profit (REF=Not-for-profit/other) | 2.60* (1.35-5.02) | 2.38* (1.30-4.38) | 2.12 (0.92-4.87) | |

| Standalone for- profit (REF=Not-for-profit/other) | 1.27 (0.61-2.65) | 1.69 (0.88-3.23) | 1.95 (0.83-4.60) | ||

| Aide works more than 1 job | Yes | 0.74 (0.39-1.42) | 0.83 (0.44-1.56) | 0.95 (0.51-1.80) | |

| Age | <30 (REF=55 and over) | 2.69 (0.92-7.81) | 2.96* (1.09-8.05) | 2.59 (0.74-9.06) | |

| 30-54 (REF=55 and over) | 1.61 (0.77-3.37) | 1.68 (0.85-3.32) | 1.89 (0.84-4.25) | ||

| Race | Other (REF=White only) | 0.91 (0.28-2.89) | 0.93 (0.33-2.62) | 1.43 (0.43-4.76) | |

| Black only (REF=White only) | 2.19* (1.18-4.06) | 2.32* (1.27-4.25) | 1.64 (0.79-3.40) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | Yes | 0.92 (0.27-3.11) | 0.79 (0.29-2.13) | 0.57 (0.18-1.76) | |

| MSA status of agency | Neither (REF=Metropolitan) | 0.70 (0.37-1.33) | 0.63 (0.32-1.25) | 0.69 (0.18-2.62) | |

| Micropolitan (REF=Metropolitan) | 1.19 (0.55-2.57) | 1.12 (0.53-2.39) | 0.6 (0.23-1.59) | ||

| Computed hourlywage | 1.00 (0.92-1.06) | 1.00 (0.94-1.07) | 0.99 (0.93-1.05) | ||

| State Unemployment rate, 2007 | 1.10 (0.86-1.41) | 1.05 (0.83-1.33) | 1.54* (1.11-2.14) | ||

| 2 Pseudo-R (Cox& Snell, 1989) | 0.186 | 0.303 | 0.243 | 0.241 | |

Discussion

This analysis is the first nationally representative study to examine the extent to which workplace and agency characteristics, job stressors/demands, and compensation are associated with agency-based home health workers’ job satisfaction and intent to leave the job. The findings support some of the hypothesized relationships articulated in the study’s conceptual framework. With respect to the hypothesized positive correlation between perceived workplace characteristics and satisfaction with the job, the analyses indicate that feeling respected by one’s supervisor, feeling valued by one’s agency, and perceived involvement in challenging work were all associated with greater job satisfaction. Workers employed in agencies that encouraged them to discuss client care with the family--a measure of aide empowerment--also had greater odds of being extremely satisfied.

The hypothesis linking the availability of benefits and compensation with higher job satisfaction was only partially supported by the observed positive correlation between the availability of a pension or retirement plan and greater job satisfaction. Contrary to expectations, higher wages and advancement potential were negatively correlated with job satisfaction or insignificant. This result is not inexplicable, given the endogenous relationship expected between wages and labor market satisfaction and turnover. Positive impacts of higher wages on job satisfaction may be obscured if higher wages and career ladder positions are used by agencies to retain otherwise dissatisfied workers, who would leave if paid less or did not see advancement possibilities.

The third hypothesis, that job stressors are negatively correlated with job satisfaction, received some support from this analysis. Satisfaction with hours worked was significantly correlated with job satisfaction. Aides who worked full-time and wanted fewer hours reported lower job satisfaction. On-the-job injury was also significantly associated with lower odds of being extremely satisfied.

The only agency characteristic related to job satisfaction was ownership status. Aides employed by standalone, for-profit agencies reported lower satisfaction than those working in non-profit agencies. Although not the focus of this report, this study found that several worker demographic characteristics were associated with job satisfaction. Aides with less than a high school education had significantly lower job satisfaction than more highly educated workers. Being the only worker in a household with dependent children was associated with higher odds of being somewhat satisfied versus dissatisfied. Age, ethnicity, and race had no effect on job satisfaction.

The findings from this study provide equivocal support for the four hypotheses testing the relationship between the various agency, worker, and policy-level variables and aide intention to leave the job. They also provide empirical evidence to support the conceptual model guiding this study. Job satisfaction was found to be strongly correlated with intent to leave the job, even after controlling for other agency-level and worker-level variables, including worker perceptions of the workplace environment. The hypothesized positive relationship between perceptions of the work environment and intent to leave the job was more nuanced. Aides’ perceptions of their workplace environment, including feeling valued by the organization and being involved in challenging work, trusted to make patient care decisions, and respected by the supervisor lowered the odds of intending to leave the job. This relationship, however, lost significance when job satisfaction was added to the model. A descriptive study using the same sample found the proportion of home health workers with positive ratings of their supervisors was greater for those workers intending to remain on the job (Bryant et al., in press). These analyses suggest that perceptions of the workplace environment go through job satisfaction and indirectly drive intent to leave the job.

The study did not support the hypothesis that compensation would have a negative relationship with intent to leave, with the exception of one variable. Workers employed by agencies offering health insurance were significantly less likely to consider leaving the job than those with no access to employer-sponsored health insurance.

One of the major findings of this study was the strong relationship between consistent assignment and aides’ intention to leave the job. Although the study did not find a relationship between consistent assignment and job satisfaction, aides assigned the same patients had significantly lower intentions of leaving the job. It may be that being assigned to the same patients provides a greater level of continuity and familiarity even if the job itself is not more satisfying. Additionally, attachment between aides and patients may foster a sense of responsibility on the part of aides and discourage dissatisfied workers from leaving their jobs.

The study supported the hypothesis that at least one job stressor is related to intent to leave. Aides who reported an on-the-job injury in the past 12 months not only were less satisfied with their jobs but also had more than twice higher odds of intending to leaving their jobs, even after controlling for job satisfaction. These results suggest that work-related injuries not only contribute to job dissatisfaction but may cause people to consider leaving the job because of ongoing health-related concerns or the ongoing physical demands of this type of work. Inadequate hours also influenced the workers’ employment intentions, as part-time aides who wanted more hours were more likely to consider leaving the job than those who felt the hours were “just right”. Interestingly, these workers did not report lower levels of job satisfaction, suggesting that they may be considering leaving the job for economic reasons rather than the quality of the job itself.

Among agency characteristics, being employed in a not-for-profit agency appears to have a positive association with job satisfaction, and a negative relationship with intent to leave the job. It is interesting to note that ownership status within the for-profit sector differentially affects the two outcomes. Those employed by standalone agencies reported lower satisfaction, while those employed in a chain-owned agency reported greater intent to leave. As the proportion of for-profit home health and home care agencies continues to grow, more research is needed to understand what factors are related to worker concerns with this part of the sector.

There also seems to be some different demographic characteristics driving intent to leave relative to job satisfaction. While race had no effect on job satisfaction, “Black/African-American only” aides were two times more likely to intend to leave the job than their “White only” peers. Household income was also related to employment intentions, as aides with lower incomes were significantly less likely to intend to leave their jobs than aides with household incomes over 300 percent FPL. These findings may reflect the fact that individuals with lower economic status may avoid the risk associated with seeking alternative employment or be less able to exit the labor force altogether.

Impact and Significance of Findings

Workplace Characteristics

This study supported the findings described in the literature review of positive perceptions of the workplace environment contributing to higher job satisfaction. These factors had the greatest increase in the odds of being satisfied with the job. Workplace characteristics contributed to turnover intention through job satisfaction. Home health workers who feel valued by the organization and challenged in their work may have higher job satisfaction, which can indirectly drive turnover intentions. Organizations can support the design of the job and cultural environment to enhance valuing and respecting aides and their work. In addition, agencies can foster positive relationships between home health workers and supervisors. While we did not find a significant relationship between HHA satisfaction or turnover intentions and empowerment of the aide (confidence, feeling trusted to make patient care decisions), one possible explanation is aides are not rewarded when they take on independent decision-making (Bishop et al., 2009).