September 2020

Printer Friendly Version in PDF Format (200 PDF pages)

ABSTRACT

Per Section 223(d)(7)(A) of the Protecting Access to Medicare Act (PAMA) of 2014 (Public Law 113-93), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary must submit to Congress an annual report on the use of funds provided under all demonstration programs conducted under this subsection, not later than one year after the date on which the first State is selected for a demonstration program under this subsection, and annually thereafter. Each report shall include assessments of: (1) access to community-based mental health services; (2) the quality and scope of services provided by CCBHCs; and (3) the impact of the demonstration programs on the federal and state costs of a full range of mental health services.

This 2019 report informs the third annual report to Congress and highlights participating states' CCBHC activities that have been associated with improving access to a comprehensive range of treatment and recovery support services. The range of services includes delivery of mental health, addiction, and either screening for general medical conditions or onsite access to primary care during the first year of the demonstration. It draws on qualitative findings gathered from interviews at the state level and data from surveys of CCBHCs.

Subsequent annual reports to Congress on this demonstration will include more details, benefitting from data pending on quality measures and cost reports now being collected by CCBHCs and by demonstration states as required. In addition, claims analyses will be conducted to answer the questions about the demonstration posed by Congress.

This report was prepared under contract #HHSP233201600017I between HHS's ASPE/BHDAP and Mathematica Policy Research to conduct the national evaluation of the demonstration. For additional information about this subject, you can visit the BHDAP home page at https://aspe.hhs.gov/bhdap or contact the ASPE Project Officer, Judith Dey, at HHS/ASPE/BHDAP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201. Her e-mail address is: Judith.Dey@hhs.gov.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization. This report was completed and submitted on September 19, 2019.

"

ACRONYMS

The following acronyms are mentioned in this report and/or appendices.

| ACT | Assertive Community Treatment |

|---|---|

| AOT | Assisted Outpatient Treatment |

| ASAM | American Society of Addiction Medicine |

| ASPE | HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| CCBHC | Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic |

| CMHC | Community Mental Health Center |

| CMS | HHS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| DBT | Dialectical Behavior Therapy |

| DCO | Designated Collaborating |

| DY | Demonstration Year |

| DY1 | First Demonstration Year |

| DY2 | First Demonstration Year |

| EBP | Evidence-Based Practice |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| FHQC | Federally Qualified Health Center |

| HHS | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

| HIT | Health Information Technology |

| IOP | Intensive Outpatient |

| LCSW | Licensed Clinical Social Worker |

| LGBTQ | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (or questioning) |

| MAT | Medication-Assisted Treatment |

| MH | Mental Health |

| PAMA | Protecting Access to Medicare Act |

| PPS | Prospective Payment System |

| PPS-1 | PPS First Model/Methodology |

| PPS-2 | PPS Second Model/Methodology |

| QBP | Quality Bonus Payment |

| RN | Registered Nurse |

| SAMHSA | HHS Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

| SMI | Serious Mental Illness |

| SUD | Substance Use Disorder |

| TCM | Targeted Case Management |

| VA | U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Section 223 of the Protecting Access to Medicare Act (PAMA), enacted in April 2014, authorized the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic (CCBHC) demonstration to allow states to test new strategies for delivering and reimbursing services provided in community mental health centers (CMHCs). The CCBHC demonstration aims to improve the availability, quality, and outcomes of ambulatory services provided in CMHCs and other providers by establishing a standard definition and criteria for CCBHCs and developing a new payment system that accounts for the total cost of providing comprehensive services to all individuals who seek care. The demonstration also aims to provide coordinated care that addresses both behavioral and physical health conditions.

In October 2015, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) awarded planning grants to 24 states to begin certifying providers to become CCBHCs, develop new prospective payment systems (PPS), and plan for the demonstration's implementation. To support the demonstration's first phase, HHS, as required by PAMA, developed criteria for use in certifying CCBHCs in six important areas: (1) staffing; (2) availability and accessibility of services; (3) care coordination; (4) scope of services; (5) quality and reporting; and (6) organizational authority.[1] The criteria established a minimum threshold for the structures and processes that CCBHCs should have in place to provide high-quality care, although states may exercise some discretion in implementing the criteria to reflect their particular needs.

States used the planning grants to develop infrastructure to support the CCBHC demonstration, and to select a PPS model and develop PPS rates. States chose between two broad PPS models developed by the HHS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) (although they may exercise some flexibility in operationalizing the models). The first model (PPS-1) is similar to the PPS model used by federally qualified health centers--it reimburses costs by using a fixed daily rate for all services rendered to a Medicaid beneficiary. If a state elected the PPS-1 model, CMS reimburses participating CCBHCs at a fixed daily rate for all services provided to a Medicaid beneficiary. The PPS-1 model also includes a state option to provide quality bonus payments (QBPs) to CCBHCs that meet defined quality metrics. The second model (PPS-2) reimburses costs by using a standard monthly rate per person served, with separate monthly rates that vary with beneficiaries' clinical conditions. Under the PPS-2 model, CMS reimburses participating CCBHCs at a fixed monthly rate for all services provided to a Medicaid beneficiary. The PPS-2 also includes outlier payments for costs above and beyond a specific threshold (that is, payment adjustments for extremely costly Medicaid beneficiaries). The PPS-2 model also requires bonus payments for clinics that meet defined quality metrics. Both PPS models aim to enhance Medicaid reimbursement by ensuring that reimbursement rates more closely reflect the cost of providing an enhanced scope of services. While clinics cannot reject or limit services on the basis of a client's ability to pay, CCBHCs can, however, only bill Medicaid for services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries. In addition, states must establish and publish a sliding fee discount schedule for consumers.

| TABLE ES.1. Number of CCBHCs, Demonstration Start Date, and PPS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Number of CCBHCs | Demonstration Start Date | PPS |

| Minnesota | 6 | July 1, 2017 | PPS-1* |

| Missouri | 15 | July 1, 2017 | PPS-1* |

| Nevada | 3a | July 1, 2017 | PPS-1* |

| New Jersey | 7 | July 1, 2017 | PPS-2 |

| New York | 13 | July 1, 2017 | PPS-1* |

| Oklahoma | 3 | April 1, 2017 | PPS-2 |

| Oregon | 12 | April 1, 2017 | PPS-1 |

| Pennsylvania | 7 | July 1, 2017 | PPS-1* |

| SOURCE: Mathematica/RAND review of CCBHC demonstration applications and telephone consultations with state officials. NOTES:

|

|||

In December 2016, HHS selected eight states from among the 24 that received planning grants to implement their PPS models and provide services that align with the CCBHC certification criteria. Consistent with PAMA requirements, HHS selected Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Pennsylvania based on the completeness of the scope of services that their CCBHCs will offer; the CCBHCs' ability to improve the availability of, access to, and engagement with a range of services (including assisted outpatient treatment); and their potential to expand mental health services without increasing federal spending. CCBHCs participating in the demonstration must also provide coordinated care and make available a comprehensive range of nine types of services[2] to all who seek help, including but not limited to those with serious mental illness, serious emotional disturbance, and substance use disorder (SUD). Services must be person-centered and family- centered, trauma-informed, and recovery-oriented, and the integration of physical and behavioral health care must serve the "whole person." To ensure the availability of the full scope of CCBHC services, service delivery could involve the participation of Designated Collaborating Organizations (DCO), which are entities not under the direct supervision of a CCBHC but that are engaged in a formal, contractual relationship with a CCBHC to provide selected services. CCBHCs that engage DCOs maintain clinical and financial responsibility for services provided by a DCO to CCBHC consumers, and DCOs provide services under the same requirements as CCBHCs and are reimbursed for these services directly by the CCBHC. In addition, CCBHCs and participating states must be able to collect, track, and report on a wide range of encounter, outcome, cost, and quality data. As summarized in Table ES.1, 66 CCBHCs are participating across eight states; only two states elected the PPS-2 model. As of August 2019, the demonstration will end on September 13, 2019.

In September 2016, the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) contracted with Mathematica and its subcontractor, the RAND Corporation, to conduct a comprehensive national evaluation of the demonstration. ASPE is overseeing the evaluation in collaboration with CMS.

Working with these federal partners, Mathematica and RAND designed a mixed-methods evaluation to examine the implementation and outcomes of the demonstration and to provide information for HHS to include in its reports to Congress. Specifically, Section 223 of PAMA mandates that HHS's reports to Congress must include: (1) an assessment of access to community-based mental health services under Medicaid in the area or areas of a state targeted by a demonstration program as compared to other areas of the state; (2) an assessment of the quality and scope of services provided by CCBHCs as compared to community-based mental health services provided in states not participating in a demonstration program and in areas of a demonstration state not participating in the demonstration; and (3) an assessment of the impact of the demonstration on the federal and state costs of a full range of mental health services (including inpatient, emergency, and ambulatory services). To date, the evaluation has focused on providing critical information to Congress and the larger behavioral health community about the strategies that CCBHCs employ to improve care. As more data become available, the evaluation will describe the effects of the demonstration on consumer outcomes and costs.

In June 2018, Mathematica and RAND submitted to ASPE a report titled "Interim Implementation Findings from the National Evaluation of the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic Demonstration," which described--through April 2018--the progress that states and CCBHCs made in implementing the demonstration and their successes and challenges. The current report provides updated information on implementation of the demonstration through April 2019 (approximately the first 22 months of the demonstration for six states and 24 months for the remaining two states). The findings in this report draw on data collected from interviews with state Medicaid and behavioral health agency officials and progress reports submitted by all participating CCBHCs (hereafter referred to as clinics). Unless otherwise noted, the 2018 and 2019 findings in this report are based on the number of clinics participating in the demonstration at the time of data collection each year (67 CCBHCs in 2018, and 66 CCBHCs in 2019 respectively).[3]

The clinic profiles in the report are based on site visits to CCBHCs in four states. In future reports, we will examine the impact of the demonstration on health care utilization, quality, and costs, using claims data and information submitted by CCBHCs and states. In August 2019, we will submit a separate report that summarizes states' and clinics' experiences with the required quality measures (based on interview and site visit data) and costs (using data from the CCBHC cost-reporting template).[4]

Implementation Findings

During the demonstration, states and CCBHCs have focused on increasing access to care, maintaining the staffing and scope of services requirements in the certification criteria, and ensuring coordinated care for CCBHC clients. Although some CCBHCs experienced early implementation challenges related to staffing or the implementation of new services, state officials reported that the CCBHCs addressed these challenges and appear to be adhering to the certification criteria in the second demonstration year.

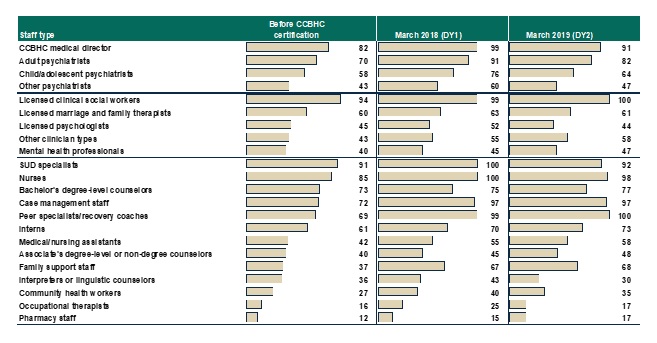

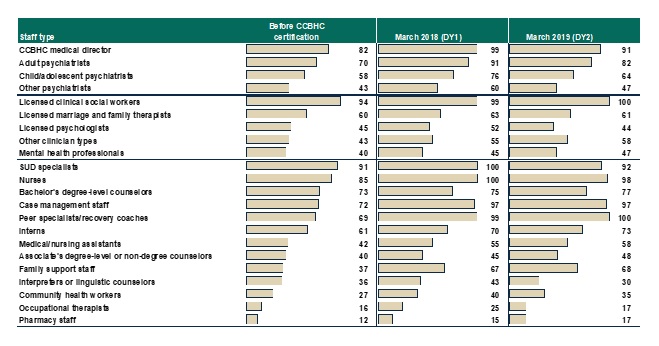

Most CCBHCs hired additional staff as part of the certification process. As shown in Figure ES.1 and detailed in Appendix Table A.1, most CCBHCs already employed licensed clinical social workers (LCSWs), SUD specialists, nurses, a medical director, bachelor's degree-level counselors, case managers, adult psychiatrists, and peer specialists/recovery coaches before they received certification. The CCBHCs most often hired case managers, peer specialists/recovery coaches, and family support workers, perhaps reflecting the criteria's focus on enhancing care coordination and person-centered and family-centered care. In addition, CCBHCs often hired various types of nurses and child/adolescent psychiatrists to provide the full scope of required services. Although states had the latitude to determine the specific types of staff their CCBHCs must employ, as of March 2018 (Demonstration Year 1 [DY1]), nearly all CCBHCs employed the types of staff mentioned in the CCBHC certification criteria.

CCBHCs' ability to maintain the required types of staff throughout the demonstration varied by staff type. For example, as shown in Figure ES.1, there was no substantial difference between DY1 and second Demonstration Year (DY2) in the proportion of clinics that employed the following staff types: LCSWs, nurses, associate's degree-level or non-degree counselors, case management staff, peer specialists/recovery coaches, licensed psychologists, other clinician types, mental health professionals, family support staff, and community health workers. However, the proportion of clinics that employed psychiatrists declined from DY1 to DY2. Seventy-six percent of clinics employed child psychiatrists in DY1 versus 64 percent in DY2. Likewise, 91 percent of clinics employed adult psychiatrists in DY1 versus 82 percent in DY2. There was also a 13 point decline from DY1 to DY2 in the percentage of clinics that employed interpreters or linguistic counselors. Such changes in staffing may suggest clinics' efforts to experiment and identifying ways to use staff and resources more efficiently. CCBHCs and states reported that clinics faced several ongoing challenges associated with hiring and retaining staff, including, for example, uncertainty around the future of the demonstration, retaining enough of each staff type to meet increased demand for services, and increases in caseloads and responsibilities leading to staff burnout. However, officials generally perceived that clinics effectively used strategies such as increased salaries and benefits to overcome challenges.

| FIGURE ES.1. Proportion of CCBHCs that Employed Specific Types of Staff Before Certification and in March 2018 (DY1) and March 2019 (DY2) |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: CCBHC Annual Progress Report Demonstration Year 1 and Year 2 data collected by Mathematica and the RAND Corporation, March 2018 and March 2019. NOTES: Denominator is 67 CCBHCs for "Proportion of CCBHCs that employed staff type before certification" and March 2018 findings, and 66 CCBHCs for March 2019 findings. See Appendix Table A.1 for detailed findings and number of clinics corresponding to the percentages. See Appendix Table A.2 for state-level findings. These findings were generally consistent across states, with the exception of Minnesota and Pennsylvania, where the proportion of clinics employing each type of staff did not decrease from 2018 to 2019. Consistent with the CCBHC cost-reporting template, the mental health professional category includes only providers trained and credentialed for psychological testing. "Other clinician types" is a write-in category. |

In the second year of the demonstration, officials in all but one state cited uncertainty around the future of the demonstration as the most significant staffing challenge for clinics. State officials reported that the uncertainty has adversely affected clinics' ability to retain staff and maintain workforce morale as the demonstration draws to a close, noting that clinics have been reluctant to add new positions or fill vacancies for fear of not being able to sustain those staff positions after the demonstration ends.

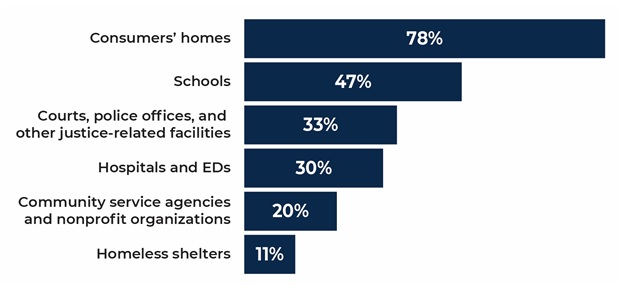

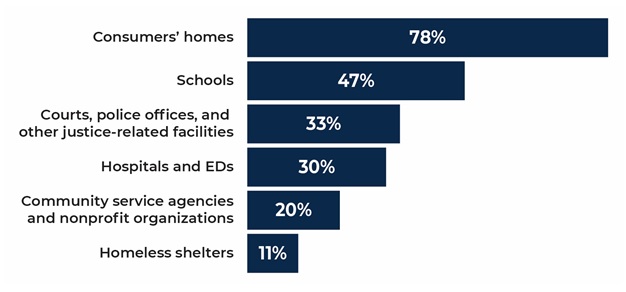

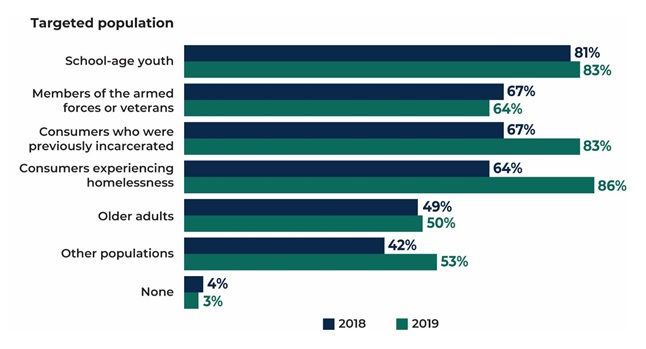

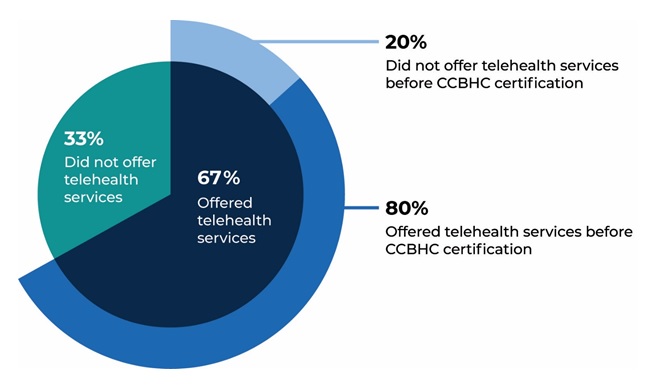

CCBHCs have worked throughout the demonstration to make services more convenient and tailored to the needs of specific populations. As reported by states, the most common strategy used by CCBHCs to increase access to care was to introduce open-access scheduling. In addition, as shown in Figure ES.2, CCBHCs provided services in locations outside of the clinic, such as consumers' homes and community service agencies like Social Security offices and community centers, in both demonstration years. Clinics also have continued to make broad use of telehealth to extend the reach of CCBHC services. Clinics have used a variety of other strategies to improve accessibility, such as conducting outreach to new and underserved populations, and remodeling the physical space of clinics to accommodate the delivery of new services (such as detoxification and physical health screening and monitoring) Stakeholder organizations representing consumers and their family members reported that the strategies CCBHCs have employed, such as open-access and expanded hours of service provision, have significantly improved access to care for CCBHC clients in their states.

| FIGURE ES.2. Proportion of CCBHCs that Provided Services Outside of Physical Clinic Space in the Past 12 Months |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: CCBHC Annual Progress Report Demonstration Year 2 data collected by Mathematica and the RAND Corporation, March 2019. NOTES: The denominator is the number of CCBHCs that reported offering services outside of the CCBHC physical buildings in the past 12 months as of March 2019 (n = 64). See Appendix Table A.6 for 2018 findings. See Appendix Table A.7 for state-level findings. The majority of clinics in all 8 demonstration states offered services outside of the CCBHC as of 2018, increasing to 100% of all CCBHCs as of 2019 in all states except New Jersey. |

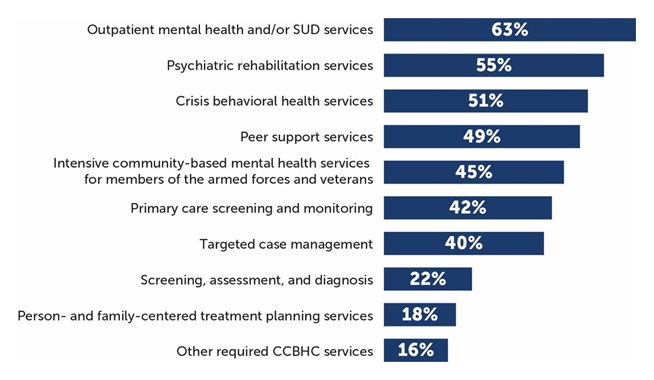

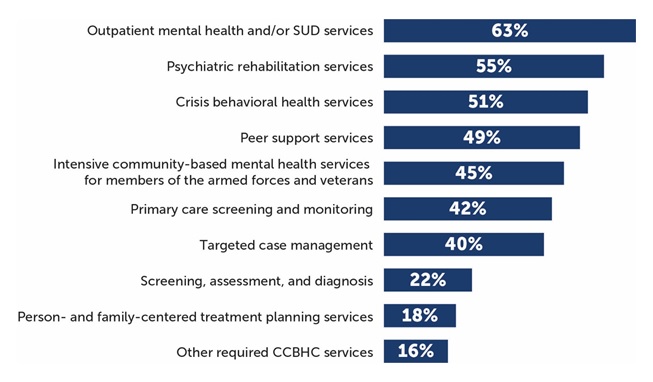

Most CCBHCs expanded their scope of services to meet the certification requirements. Clinics most often added services within the categories of outpatient mental health and/or SUD services, psychiatric rehabilitation services, crisis services, peer support, services for members of the armed forces and veterans, and primary care screening and monitoring (Figure ES.3). The extent to which the CCBHCs added services to meet the certification requirements varied widely across the states depending on the service infrastructure that existed before the demonstration.

| FIGURE ES.3. Proportion of CCBHCs that Added Each Type of Service as a Result of Certification (as of March 2018) |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: CCBHC Annual Progress Report Demonstration Year 1 data collected by Mathematica and the RAND Corporation, March 2018. NOTES: Denominator is 67 CCBHCs. See Appendix Table A.11 for detailed findings on individual services. CCBHCs may have provided services within each of the service categories illustrated in the figure before CCBHC certification. For example, all clinics provided some type of outpatient mental health and/or SUD treatment before certification. However, 63% of clinics added some type of outpatient mental health and/or SUD treatment as a result of certification. The service categories illustrated in this figure correspond to the service categories described in the CCBHC certification criteria. |

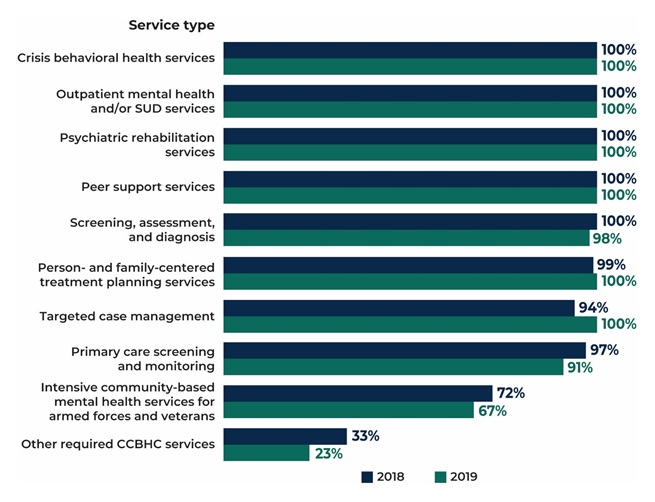

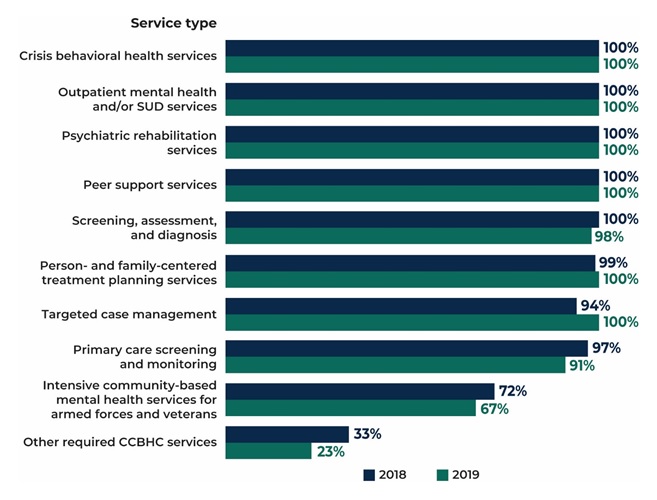

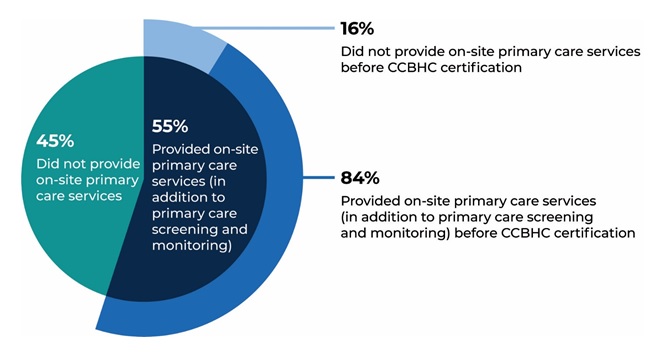

Officials in all states perceived that clinics were able to sustain delivery of the nine core CCBHC services throughout the demonstration, a finding confirmed by clinics in the progress report. As shown in Figure ES.4, nearly all CCBHCs in both DY1 and DY2 reported that they provided the required services, with the exception of intensive community-based mental health services for members of the armed forces and veterans, which were provided by about 70 percent of clinics in both years. State officials speculated that the armed forces/veterans populations did not comprise a large percentage of CCBHC clients and that CCBHCs may have struggled to engage these populations and to develop strong referral relationships and care coordination agreements with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs providers. Though not required by the demonstration, about half of clinics provided on-site primary care in each demonstration year.

| FIGURE ES.4. Proportion of CCBHCs that Provided Each Type of Service Either Directly or Through a DCO |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: CCBHC Annual Progress Report Demonstration Year 1 and Year 2 collected by Mathematica and the RAND Corporation, March 2018 and March 2019. NOTES: Denominator is 67 CCBHCs in 2018 (DY1) and 66 CCBHCs in 2019 (DY2). The "other required CCBHC services" category denotes additional services that do not fall within the 9 service types defined in federal criteria but that may be required by individual states. See Appendix Table A.12 for detailed findings and the number of clinics corresponding to the percentages. See Appendix Table A.13 for state-level findings. |

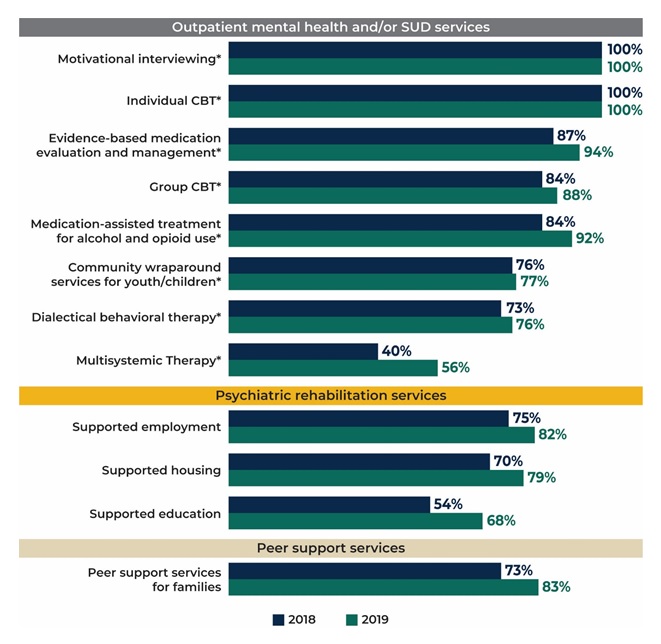

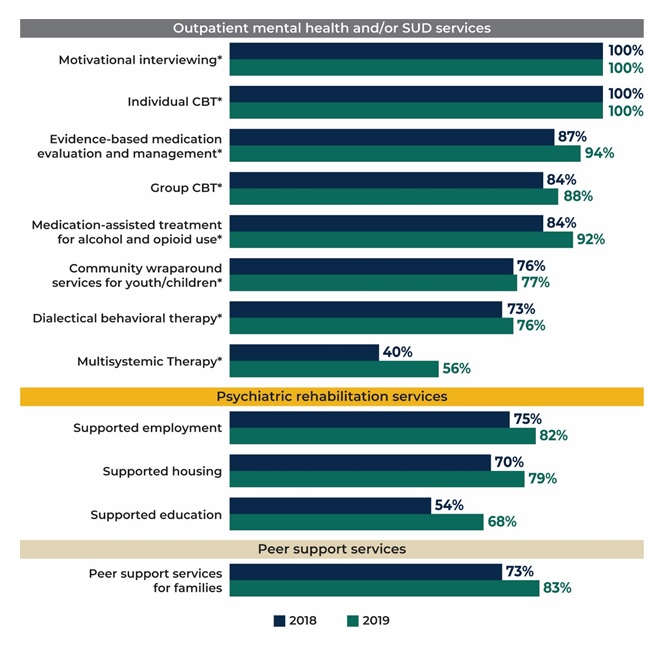

CCBHCs were able to add and sustain a range of evidence-based practices (EBPs) across demonstration years. In the first year of the demonstration, CCBHCs offered a wide range of EBPs and psychiatric rehabilitation and other services either directly or through DCOs. As shown in Figure ES.5, most clinics were able to sustain or provide more of these services in the second year of the demonstration. For example, 46 percent (n = 31) of clinics added medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for alcohol or opioid use as a result of certification, and 92 percent of clinics (n = 61) offered MAT in DY2 compared to 84 percent (n = 56) in DY1. Even though, early in the demonstration, CCBHCs generally addressed challenges to maintaining EBPs and providing the full scope of CCBHC services, officials continued to explore ways to support clinics in offering the full range of services, such as by providing CCBHCs with increased flexibility to better tailor EBPs and other services to reflect the needs and preferences of their client populations.

CCBHCs have used a variety of strategies to improve care coordination, including adding various provider types to treatment teams and expanding targeted care coordination strategies to different populations and service lines. In the early stages of the demonstration, improvements to electronic health records (EHR) and health information technology aided clinics in their care coordination efforts, in some cases permitting CCBHCs to integrate care plans more fully, connect with external providers, and receive alerts about clients' care transitions. As the demonstration progressed, clinics implemented additional strategies, and initiated collaboration with various external organizations to facilitate coordinated care. For example, some clinics partnered with first responders and law enforcement officials on strategies to intervene in crisis situations and divert those in crisis from the criminal justice system.

CCBHCs, for the most part, elected to offer the full scope of CCBHCs services directly, instead of engaging separate organizations to deliver required services. While the certification criteria allowed for some services to be provided by DCOs, officials suggested that CCBHCs preferred to provide services directly because they wished to embrace the model fully and were reluctant to assume oversight responsibility for another provider's services. CCBHCs did, however, continue to provide and expand services in collateral agencies such as schools and shelters and to build and sustain close formal and informal relationships with a range of external providers.

| FIGURE ES.5. Proportion of CCBHCs that Provided Selected EBPs, Psychiatric Rehabilitation Services, and Other Services, Either Directly or Through a DCO |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: CCBHC Annual Progress Report Demonstration Year 1 and Year 2 collected by Mathematica and the RAND Corporation, March 2018 and March 2019. NOTES: Denominator is 67 CCBHCs in 2018 and 66 CCBHCs in 2019. See Appendix Table A.12 for detailed findings and the number of clinics corresponding to the percentages. See Appendix Table A.11 for the number and percentage of clinics that added each type of service as a result of CCBHC certification. See Appendix Table A.13 for state-level findings. * = EBP listed in CCBHC criteria. |

Future Evaluation Activities

In August 2019, we will submit a report summarizing information from the first year of CCBHC cost reports. The report will also draw on information from interviews and site visits to describe clinics' experience with the PPS and the progress that CCBHCs and states are making toward submission of the required quality measures. We will update the report in August 2020 to include information from the second year of CCBHC cost reports and will summarize the quality of care provided to CCBHC consumers by using data from the CCBHC-reported and state-reported quality measures.

We are in the process of obtaining Medicaid claims and encounter data from states to examine changes in service utilization and costs. We plan to examine the impacts of CCBHC services on: (1) hospitalization rates; (2) emergency department service utilization; and (3) ambulatory care relative to within-state comparison groups (Medicaid beneficiaries with similar diagnostic and demographic characteristics who did not receive care from CCBHCs). Depending on the availability of data within each state, we expect that the impact analyses will use approximately four years of Medicaid claims/encounter data (up to a two-year pre-demonstration period and a two-year post-implementation period). We will report these findings in our final report in May 2021, along with updated findings that draw on both years of CCBHC cost reports and quality measures.

I. BACKGROUND

A. Description of the CCBHC Demonstration

In April 2014, Section 223 of the Protecting Access to Medicare Act (PAMA) authorized the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic (CCBHC) demonstration to allow states to test new strategies for delivering and reimbursing services provided in community mental health centers (CMHCs). The CCBHC demonstration aims to improve the availability, quality, and outcomes of ambulatory services provided in CMHCs by establishing a standard definition and criteria for CCBHCs and developing a new payment system that accounts for the total cost of providing comprehensive services to all individuals who seek care. The demonstration also aims to provide coordinated care that addresses both behavioral and physical health conditions.

In October 2015, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) awarded planning grants to 24 states to begin certifying CMHCs to become CCBHCs, develop new prospective payment systems (PPS), and plan for the demonstration's implementation. To support the demonstration's first phase, HHS, as required by PAMA, developed criteria for use in certifying CCBHCs in six important areas: (1) staffing; (2) availability and accessibility of services; (3) care coordination; (4) scope of services; (5) quality and reporting; and (6) organizational authority.[5] The criteria established a minimum threshold for the structures and processes that CCBHCs should have in place to provide high-quality care, although states may exercise some discretion in implementing the criteria to reflect their particular needs.

States used the planning grants to develop infrastructure to support the CCBHC demonstration, and to select a PPS model and develop PPS rates. States chose between two broad PPS models developed by the HHS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) (although they may exercise some flexibility in operationalizing the models). The first model (PPS-1) is similar to the PPS model used by federally qualified health centers (FHQCs)--it reimburses costs by using a fixed daily rate for all services rendered to a Medicaid beneficiary. If a state elected the PPS-1 model, CMS reimburses participating CCBHCs at a fixed daily rate for all services provided to a Medicaid beneficiary. The PPS-1 model also includes a state option to provide quality bonus payments (QBPs) to CCBHCs that meet defined quality metrics. The second model (PPS-2) reimburses costs by using a standard monthly rate per person served, with separate monthly rates that vary with beneficiaries' clinical conditions. Under the PPS-2 model, CMS reimburses participating CCBHCs at a fixed monthly rate for all services provided to a Medicaid beneficiary. The PPS-2 also includes outlier payments for costs above and beyond a specific threshold (that is, payment adjustments for extremely costly Medicaid beneficiaries). The PPS-2 model also requires bonus payments for clinics that meet defined quality metrics. Both PPS models aim to enhance Medicaid reimbursement by ensuring that reimbursement rates more closely reflect the cost of providing an enhanced scope of services. The use of a PPS provides a unique opportunity for states and CCBHCs to develop rates based on the expected cost of care that accounted for total costs associated with delivering the nine required services to Medicaid beneficiaries. This included the ability to use a mix of staffing models, as well as pay for services that were allowed under the demonstration, but might not have been traditionally covered under Medicaid, such as those that do not involve face-to-face contact with the consumer. These PPS reflect HHS's broader strategy of encouraging the development of a health care system that results in better care, smarter spending, and healthier people. While clinics cannot reject or limit services on the basis of a client's ability to pay, CCBHCs can, however, only bill Medicaid for services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries. In addition, states must establish and publish a sliding fee discount schedule for clients.

In December 2016, HHS selected eight states from among the 24 that received planning grants to implement their PPS models and provide services that align with the CCBHC certification criteria. Consistent with PAMA requirements, HHS selected Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Pennsylvania based on the completeness of the scope of services their CCBHCs will offer; the CCBHCs' ability to improve the availability of, access to, and engagement with a range of services (including assisted outpatient treatment [AOT]); and their potential to expand mental health services without increasing federal spending. CCBHCs participating in the demonstration must also provide coordinated care and make available a comprehensive range of nine types of services[6] to all who seek help, including but not limited to those with serious mental illness (SMI), serious emotional disturbance (SED), and substance use disorder (SUD). Services must be person-centered and family-centered, trauma-informed, and recovery-oriented, and the integration of physical and behavioral health care must serve the "whole person." To ensure the availability of the full scope of CCBHC services, service delivery could involve the participation of other Designated Collaborating Organizations (DCO), which are entities not under the direct supervision of a CCBHC but that are engaged in a formal relationship with a CCBHC to provide selected services. DCOs provide services under the same requirements as CCBHCs. CCBHCs that engage DCOs maintain clinical and financial responsibility for services provided by a DCO to CCBHC consumers, and directly reimburse DCOs for provided services. CCBHCs and participating states must be able to collect, track, and report on a wide range of encounter, outcome, cost, and quality data. As summarized in Table I.1, 66 CCBHCs are participating across eight states; only two states elected the PPS-2 model. As of August 2019, the demonstration will end on September 13, 2019.

| TABLE I.1. Number of CCBHCs, Demonstration Start Date, and PPS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Number of CCBHCs | Demonstration Start Date | PPS |

| Minnesota | 6 | July 1, 2017 | PPS-1* |

| Missouri | 15 | July 1, 2017 | PPS-1* |

| Nevada | 3a | July 1, 2017 | PPS-1* |

| New Jersey | 7 | July 1, 2017 | PPS-2 |

| New York | 13 | July 1, 2017 | PPS-1* |

| Oklahoma | 3 | April 1, 2017 | PPS-2 |

| Oregon | 12 | April 1, 2017 | PPS-1 |

| Pennsylvania | 7 | July 1, 2017 | PPS-1* |

| SOURCE: Mathematica/RAND review of CCBHC demonstration applications and telephone consultations with state officials. NOTES:

|

|||

1. Goals of the National Evaluation

In September 2016, the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) contracted with Mathematica and its subcontractor, the RAND Corporation, to conduct a comprehensive national evaluation of the demonstration. ASPE is overseeing the evaluation in collaboration with CMS.

Working with these federal partners, Mathematica and RAND designed a mixed-methods evaluation to examine the implementation and outcomes of the demonstration and to provide information for HHS to include in its reports to Congress. Specifically, Section 223 of PAMA mandates HHS's reports to Congress to include: (1) an assessment of access to community-based mental health services under Medicaid in the area or areas of a state targeted by a demonstration program as compared to other areas of the state; (2) an assessment of the quality and scope of services provided by CCBHCs as compared to community-based mental health services provided in states not participating in a demonstration program and in areas of a demonstration state not participating in the demonstration; and (3) an assessment of the impact of the demonstration on the federal and state costs of a full range of mental health services (including inpatient, emergency, and ambulatory services). To date, the evaluation has focused on providing critical information to Congress and the larger behavioral health community about the strategies that CCBHCs employ to improve care. As more data become available, the evaluation will describe the effects of the demonstration on consumer outcomes and costs.

2. Purpose of Report

In June 2018, Mathematica and RAND submitted to ASPE a report titled "Interim Implementation Findings from the National Evaluation of the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic Demonstration," which described--through April 2018--the progress that states and CCBHCs made in implementing the demonstration and their successes and challenges. The current report provides updated information on the implementation of the demonstration through April 2019 (approximately the first 22 months of the demonstration for six states and 24 months for the remaining two states). The findings in this report draw on data collected from interviews with state Medicaid and behavioral health agency officials and progress reports submitted by all participating CCBHCs (hereafter referred to as clinics). The clinic profiles in the report are based on site visits to CCBHCs in four states. Chapter II of the report describes the data collection and analytic methods. Chapter III provides updated findings on implementation progress, successes, and challenges with respect to CCBHCs' staffing (Chapter III.A), access to care (Chapter III.B), scope of services (Chapter III.C), and care coordination (Chapter III.D). The final chapter summarizes overarching themes that emerged from our analysis and briefly describes next steps for the evaluation. In future reports, we will examine the impact of the demonstration on health care utilization, quality, and costs, using claims data and information submitted by CCBHCs and states. In August 2019, we will submit a separate report that summarizes states' and clinics' experiences with the required quality measures (based on interview and site visit data) and costs (using data from the CCBHC cost-reporting template).[7]

II. METHODS

The findings in this report are based on: (1) responses to progress reports each clinic completed in spring 2018 and 2019; (2) three rounds of interviews with state Medicaid and behavioral health officials; and (3) site visits to clinics in four demonstration states.

CCBHC progress reports. In spring 2018 (Demonstration Year 1 [DY1]), clinics submitted an online progress report that included information about their staffing, training, accessibility of services, scope of services, electronic health record (EHR)/health information technology (HIT) capabilities, care coordination activities, and relationships with other providers. Clinics submitted a second progress report in spring 2019 to report on Demonstration Year 2 (DY2) activities (the 2018 and 2019 progress report templates appears in Appendix B). Questions in the DY2 progress report were almost identical to those in the DY1 progress report, with a few minor changes to streamline data collection for clinics and update the timeframes referenced by the questions. In collaboration with the CCBHC demonstration program leadership in each state, we conducted extensive outreach to clinic leaders via telephone and email before and during collection of the progress reports to encourage clinics' participation and answer any questions. In 2018, all 67 participating clinics completed the progress report. In 2019, the remaining 66 clinics completed the report. At both time points, all participating CCBHCs completed the progress reports--a 100 percent response rate.[8] Unless otherwise noted, the 2018 and 2019 findings in this report are based on the number of clinics participating in the demonstration at the time of data collection each year (67 CCBHCs in 2018, and 66 CCBHCs in 2019 respectively).

We computed descriptive statistics (for example, means, percentages) by using Excel and SAS to analyze the clinic progress report data. We summarize findings across all clinics and within each state. However, readers should interpret state-level variation in the findings cautiously, given that some states such as Nevada and Oklahoma account for a small number of clinics participating in the demonstration (n = 3 each), whereas others, such as New York and Missouri, have over a dozen clinics. In addition, the service systems and policy context in which clinics operate vary considerably across states, posing a challenge to direct cross-state comparisons. Finally, although we compare across the first and second demonstration years across similar items, we focus in this report on the status of implementation as of March 2019 (three months prior to the end of DY2), when the clinics submitted their second progress reports to us. CCBHCs have also continued to make changes and implement new programs and procedures since completion of the progress reports as they approach the end of the demonstration period; thus, the progress report findings reported here do not capture the most recent developments.

Telephone interviews. We conducted three rounds of telephone interviews with state behavioral health and Medicaid officials involved in leading implementation of the CCBHC demonstration in each state. We conducted the first round of interviews early in DY1--September and October 2017. We conducted the second round from February to March 2018 and the third round from February to April 2019. The first round of interview questions gathered information about early implementation, decisions made during the demonstration planning phase, early successes and challenges in fulfilling the certification requirements and following the data collection and monitoring procedures, and projected challenges or barriers to successful implementation. The second round of interviews gathered information on interim successes and challenges since the initial interview; successes in implementing demonstration cost-reporting procedures and quality measures; and early experiences with the PPS systems. The third round of interviews collected information on implementation successes and challenges in the second demonstration year. The interview guides for each round appear in Appendix C.

We conducted 29 state official interviews (ten interviews during the first two rounds and nine during the third). In seven states, the behavioral health and Medicaid officials asked to participate in the interviews together to reduce scheduling burden and provide comprehensive answers.[9] Each state interview required approximately 90 minutes. In the third round, we also conducted interviews with consumer and family representative organizations in four states in order to gather the perspective of consumers and families on the demonstration.

Two researchers conducted each interview, with one leading the interview and one taking notes. We asked interviewees' permission to audio record the discussions for purposes of confirming the accuracy and completeness of interview notes. Following the interviews, to expedite analysis, we organized the interview information into categories defined by the CCBHC certification criteria. We summarized interviewees' responses about implementation experiences within each domain of the certification criteria covered by this report (that is, staffing; access to care; scope of services; care coordination) separately for each state and then identified cross-state themes in the findings.

Site visits. We conducted site visits to two clinics in each of four demonstration states in February and March 2018. In collaboration with ASPE, we selected the four states to visit: Missouri, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Pennsylvania.[10] Using information from clinic responses to the progress report and interview transcripts, we selected two clinics within each state to visit that varied in terms of the following characteristics: urban-rural designation, location and proximity to other CCBHCs, size and number of CCBHC service locations, implementation of intensive team-based supports, Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), medication-assisted treatment (MAT), and any innovative engagement strategies or mobile/community-based supports that clinics' reported in their progress reports or that we learned about during interviews with state officials. During the site visits, we conducted in-depth discussions with clinic administrators and frontline clinical staff about how care has changed following implementation of the demonstration. Interview topics included successes and barriers related to CCBHC staffing, steps clinics have taken to improve access to care and expand their scope of services, CCBHCs' experience with payments and the PPS, and quality reporting practices. The interview guides for each staff type appear in Appendix D. We asked interviewees' permission to audio record the discussions to facilitate our analysis. Following the interviews, we organized the interview information into categories defined by the CCBHC certification criteria to facilitate analysis and to develop the clinic profiles in Chapter III.

III. IMPLEMENTATION FINDINGS

This chapter updates interim findings on the implementation of the demonstration presented in our June 2018 report to incorporate data gathered through April 2019. The chapter presents findings on implementation progress, successes, and challenges with respect to CCBHC staffing (Chapter III.A), access to care (Chapter III.B), scope of required services (Chapter III.C), and care coordination (Chapter III.D).

A. Staffing

The certification criteria require CCBHCs to maintain staff appropriate to providing comprehensive behavioral health care. The criteria include some specific staffing requirements; for example, clinics are required to have a psychiatrist serving in the role of medical director[11] as well as the following staff: a medically trained behavioral health care provider who can prescribe and manage medications independently under state law; credentialed SUD specialists; and individuals with expertise in addressing trauma and promoting the recovery of children and adolescents with SED and adults with SMI and/or SUD. However, the certification criteria allow states flexibility to develop more detailed plans for appropriately staffing CCBHCs according to their existing systems of licensure and accreditation and based on the needs of the populations served by the states' CCBHCs. The criteria provides examples of CCBHC staff types states could require, including the following: (1) psychiatrists (including child, adolescent, and geriatric psychiatrists); (2) nurses trained to work with consumers across the lifespan; (3) licensed independent clinical social workers; (4) licensed mental health counselors; (5) licensed psychologists; (6) licensed marriage and family therapists; (7) licensed occupational therapists; (8) staff trained to provide case management; (9) peer specialists/recovery coaches; (10) licensed addiction counselors; (11) staff trained to provide family support; (12) medical assistants; and (13) community health workers.[12] The certification criteria also require CCBHCs to provide staff training in a variety of topics, including provision of culturally competent care, patient-centered care, risk assessment, suicide prevention, and suicide response.

This section of the report summarizes: (1) the types of staff that clinics hired; (2) the challenges that clinics encountered in maintaining the required staff during the demonstration; and (3) the types of training that CCBHC staff received since the demonstration's outset.

1. What Types of Staff did CCBHCs Hire as a Result of Certification?

CCBHCs employed a wide variety of clinical staff before the demonstration. As shown in Figure III.1, before CCBHC certification, most clinics employed licensed clinical social workers (LCSWs), SUD specialists, nurses, a medical director, bachelor's degree-level counselors, case managers, adult psychiatrists, peer specialists/recovery coaches, and child/adolescent psychiatrists. However, before CCBHC certification, fewer clinics employed family support staff, community health workers, interpreters or linguistic counselors, occupational therapists, and mental health professionals trained and credentialed to provide psychological testing.

Interviews with state officials suggested that variation across clinics in the types of staff that they employed before the demonstration was related in part to the types of services the clinic historically provided. For example, before the demonstration, the CCBHCs in Nevada focused primarily on the delivery of treatment for SUD, whereas the CCBHCs in New York primarily provided services for mental health disorders. Consequently, Nevada's CCBHCs had relatively few mental health providers on staff before the demonstration, whereas New York's CCBHCs employed a broad range of mental health providers but fewer substance use treatment providers.

Officials across all states reported that clinics were able to ramp up quickly and begin hiring staff as the demonstration began; they succeeded in filling the required staff positions in the first demonstration year. Officials in one state, for example, noted that its clinics created and filled 167 new staff positions during the demonstration's first year. Accordingly, as of March 2018 (DY1 Progress Report), the majority of clinics reported employing staff to fulfill the following positions, which are required or recommended in the certification criteria:

-

Ninety-nine percent of clinics (n = 66) reported employing a CCBHC medical director compared to 82 percent (n = 55) before certification (Figure III.1). Ninety-one percent of clinics (n = 61) reported employing a psychiatrist as medical director (not shown in Figure III.1). In the few clinics that did not have psychiatrists as medical directors, clinics hired psychiatric nurse practitioners to fulfill the role of director, as permitted by the CCBHC criteria when psychiatrists are unavailable because of workforce shortages.

-

Ninety-one percent of clinics (n = 61) employed adult psychiatrists compared to 70 percent (n = 47) before certification.

-

Seventy-six percent of clinics (n = 51) employed child/adolescent psychiatrists compared to 58 percent (n = 39) before certification.

-

All clinics employed SUD specialists compared to 91 percent (n = 61) before certification.

After the certification process, a substantially larger proportion of CCBHCs employed case managers, peer specialists/recovery coaches, child/adolescent psychiatrists, and family support workers in DY1 than before certification. For example, 69 percent of clinics (n = 46) employed peer specialists/recovery coaches before certification; by DY1, however, almost all did so (n = 66; 99 percent) (Figure III.1). Likewise, only 37 percent (n = 25) of clinics employed family support staff before certification, but 67 percent (n = 45) did so in DY1. In contrast, the proportion of clinics that employed LCSWs, bachelor's degree-level counselors, and mental health professionals trained and credentialed for psychological testing before the demonstration did not change substantially as a result of certification. These findings varied somewhat across states, given differences in the treatment focus of CCBHCs before the demonstration (state-level findings appear in Appendix Table A.2).

In several open-ended questions in the progress report, clinics reported that they hired specific types of nurses and other clinical staff as part of the certification process (not shown in Figure III.1). For example, in DY1:

-

Fifty-eight percent of clinics (n = 38) hired registered nurses (RNs), especially RNs with psychiatric experience (n = 11; 16 percent of CCBHCs).

-

Thirteen percent of clinics (n = 9) hired nurses with SUD experience (one clinic reported hiring a nurse with experience in providing MAT for SUD).

-

Fifty-five percent of clinics (n = 37) reported hiring "other clinician types." The most common of these other staff types were licensed professional counselors (n = 10; 15 percent of clinics), qualified mental health professionals or licensed mental health counselors (n = 7; 10 percent of clinics),[13] and licensed master social workers (n = 5; 8 percent of clinics).

In interviews, officials in several states suggested that the enhanced payment rates provided as part of the PPS may have played an important role in helping CCBHCs build their provider workforce by allowing CCBHCs to offer higher salaries and hire different types or greater numbers of staff than they previously had the capacity to employ. Officials in three states reported that the enhanced payment rates under the PPS were especially helpful in hiring and retaining psychiatrists. The rates allowed clinics to offer higher salaries and better benefits than those offered by other potential employers.

State officials suggested that experiences in hiring and maintaining required staff may also have varied somewhat by geographic designation (i.e., urban versus rural areas), noting that hiring in rural communities proved more challenging, but that clinics have developed creative solutions to rural hiring challenges. For example, officials in Nevada commented that the flexibility to employ interns and cultivate a preprofessional student workforce has been helpful to CCBHCs operating in the state's rural areas. According to state officials, these rural clinics have been able to provide training, supervision, and experience to social work students and then retain those students in their workforces after graduation.

|

CCBHC Spotlight: Nurses as Key Players to Address Medical Issues in CCBHCs |

||

|---|---|---|

|

A rural CCBHC provides outpatient behavioral health services to a large number of homeless and uninsured individuals. In addition to providing the required CCBHC services, the clinic's behavioral health staff collaborate with an on-site FQHC--in a non-DCO relationship--to provide clients with access to physical health care. Before the demonstration, the clinic had one nurse on staff who served a subset of the clinic's clients. When the clinic became a CCBHC, it hired four RNs and one licensed practical nurse, and restructured and expand the nurse role to provide primary care screening and monitoring (CCBHC Requirement 4.a.1), on-site primary care services, and to coordinate physical health care with external providers. A primary focus of the nurse role under the demonstration also is to provide education to behavioral health staff on physical health topics. Clinic leadership reported that the PPS reimbursement model allowed the clinic to hire additional nursing staff, and remarked that adding nurses to the care team was "one of the biggest successes of the CCBHC demonstration."

Under the demonstration, each nurse partners with a psychiatrist in the clinic to collect labs and complete nursing assessments to collect clients' vitals and history when clients attend psychiatric appointments. Clinic leadership explained that the nurse is strategically placed with the psychiatrist as a way to encourage clients to address their physical health. The nurse introduces primary care services to clients and helps then overcome any fear or mistrust of primary care providers. Behavioral health providers and clinic leadership value the nurses in that they provide access to physical health services for clients who otherwise might not have considered engaging in physical health care. Nurses at this CCBHC also provide care coordination services for clients who receive physical health services outside of the clinic. For these clients, the nurse obtains permission from the client and calls the external provider's office to discuss plans for behavioral and physical health care and to review labs. Nurses also refer clients to medical specialists and follow up with clients to ensure that they completed the referral. If a client visits an emergency department or is hospitalized, the clinic's transition team notifies the nurse, who calls the client to review discharge instructions and medication changes, and to schedule a follow-up appointment.

The nursing staff also provides training to behavioral health providers at the CCBHC. The clinic implemented a "nurse college," a 16-week program that educates behavioral health staff on common chronic physical illnesses in the client population. One nurse explained the goal of the one-hour sessions as follows: "To introduce the clinical staff to the physical side of the clients and explaining the disease process, like diabetes and upper respiratory diseases." Behavioral health staff and clinic leadership believe that the nurse college complemented and enhanced the program's existing training opportunities and encouraged behavioral health staff to consider their clients' physical health issues and address them with their clients. CCBHC behavioral health staff also view the nurse as a valuable resource for consultation on clients' medical needs. According to behavioral health providers, the presence of nurses on-site provided staff with access to physical health expertise and reduced the burden of having to address all of the clients' concerns alone. As one provider noted, "I don't need to know everything about diabetes, I have a team I can connect you to. I can walk to a nurse and tell them I am worried about this person. Doesn't have to be my scope of practice, I just know what path to go to." One therapist echoed the sentiment, remarking that "We don't feel like we have to [address physical health needs] on our own...I can utilize the nurses. That's the great change from me being here before CCBHC." |

2. Have CCBHCs Maintained Required Staffing?

Officials across all demonstration states indicated that CCBHCs generally succeeded in meeting and maintaining the required types of staff throughout the demonstration, noting few instances of clinics struggling to sustain at least the minimum staffing requirements. Consistent with state officials' perceptions, there was no substantial difference between DY1 and DY2 in the proportion of clinics that employed the following staff types: LCSWs, nurses, associate's degree-level or non-degree counselors, case management staff, peer specialists/recovery coaches, licensed psychologists, other clinician types, mental health professionals, family support staff, and community health workers (Figure III.1).

However, fewer clinics employed the following types of staff in DY2 compared with DY1:

-

SUD specialists (92 percent of clinics in DY2 versus 100 percent in DY1).

-

CCBHC medical directors (91 percent in DY2 versus 99 percent in DY1).

-

Adult psychiatrists (82 percent in DY2 versus 91 percent in DY1), child/adolescent psychiatrists (64 percent in DY2 versus 76 percent in DY1), and other psychiatrists (47 percent in DY2 versus 60 percent in DY1).

-

Licensed psychologists (44 percent in DY2 versus 52 percent in DY1).

-

Interpreters or linguistic counselors (30 percent in DY2 versus 43 percent in DY1) and community health workers (35 percent in DY2 versus 40 percent in DY1).

-

Occupational therapists (17 percent in DY2 versus 25 percent in DY1).

CCBHCs continued to report a few ongoing challenges related to hiring and retaining staff. In DY2, 76 percent (n = 50) of clinics reported that at least one position in the required staff categories was vacant for at least 2 months during the past 12 months, a small increase of 4 percentage points from DY1. This finding was generally consistent across states (state-level findings appear in Appendix Table A.3). Clinics most frequently reported vacancies for the following positions: adult and child/adolescent psychiatrists, peer support staff/recovery coaches, SUD specialists such as licensed alcohol and drug abuse counselors, and LCSWs. (These findings were similar to findings from the DY1 progress reports.) However, in 2019, clinics reported several additional staff types as being difficult to fill, especially nursing staff and licensed professional counselors.

State officials universally echoed the responses to the clinic progress report, noting that psychiatrists were the most challenging to recruit and retain; officials also noted difficulties in hiring and maintaining the following staff types: licensed psychologists and clinical social workers, licensed alcohol and drug counselors, and peers. Officials shared that the licensure requirements and credentialing processes associated with these types of licensed staff often made it more difficult to find and onboard qualified providers than other non-licensed or credentialed staff types. Officials suggested that these staffing challenges may be related to the relative scarcity of these types of providers across the states, with the challenges particularly acute in rural and frontier communities. In addition, officials in all demonstration states remarked that, even though clinics generally were able to hire and maintain staff in the required positions, they often struggled to hire and retain enough of each staff type to meet the increased demand for clinics' services created by the demonstration. One state official in Minnesota noted that clinics "all had staffing plans in place based on their needs assessments, but there were some clinics that had increased demand beyond what their expectations were and then they needed to start hiring more staff."

| FIGURE III.1. Proportion of CCBHCs that Employed Specific Types of Staff before Certification and in March 2018 (DY1) and March 2019 (DY2) |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: CCBHC Annual Progress Report Demonstration Year 1 and Year 2 data collected by Mathematica and the RAND Corporation, March 2018 and March 2019. NOTES: Denominator is 67 CCBHCs for "Proportion of CCBHCs that employed staff type before certification" and March 2018 findings, and 66 CCBHCs for March 2019 findings. See Appendix Table A.1 for detailed findings and number of clinics corresponding to the percentages. See Appendix Table A.2 for state-level findings. These findings were generally consistent across states, with the exception of Minnesota and Pennsylvania, where the proportion of clinics employing each type of staff did not decrease from 2018 to 2019. Consistent with the CCBHC cost-reporting template, the mental health professional category includes only providers trained and credentialed for psychological testing. "Other clinician types" is a write-in category. |

In both the DY1 and DY2 progress reports, clinics described a variety of reasons for experiencing difficulty in hiring and/or retaining staff. The most common included: (1) rural or remote CCBHC locations; (2) the inability to meet salary expectations; (3) regional and state workforce shortages, especially in behavioral health; and (4) competition with other health care facilities such as hospitals and non-profit and for-profit health systems (not reported in the DY1 progress reports). Officials in three states echoed the issue of competition. For example, one official commented that "we still have some clinics that have competition with other health care systems or industries in the area and have trouble filling positions. One area in particular has hospitals, prisons, and other social service entities which are all very hard to compete with."

In the second year of the demonstration, officials in all but one state cited uncertainty around the future of the demonstration as the most significant staffing challenge for clinics. Drawing on feedback from the clinics, officials reported that the uncertainty has adversely affected their ability to retain staff and maintain workforce morale as the demonstration draws to a close. Concerns about the effects of uncertainty on staff appeared most acute in states that have not developed a plan to sustain components of the demonstration, although state officials nearly unanimously voiced the same concern. Officials in two states that are working to continue parts of the demonstration mentioned that, even though clinics have maintained the required staffing, clinic leaders have been reluctant to add new positions or fill vacancies occasioned by turnover for fear of not being able to sustain those staff positions after the demonstration concludes.

Staffing challenges cited by state officials differed somewhat in DY2 from those in DY1, and across states. In the earlier year, officials cited long-standing workforce issues, such as staff turnover and low compensation for public sector mental health positions, as the primary challenges to maintaining CCBHC staffing requirements. These officials viewed turnover not only as a barrier to CCBHC implementation but also as a more general and pervasive issue across states' behavioral health systems. During the demonstration's second year, state officials cited some specific factors associated with the CCBHC model that may have positively or negatively affected staff turnover. Two state officials perceived that increases in caseloads as a result of the expansion of services and client outreach were unmanageable and led to staff burnout. Officials also noted that the more comprehensive and collaborative nature of the CCBHC model required shifts in staff responsibilities and culture that may have led some staff to seek employment elsewhere. In contrast, officials in other states suggested that the CCBHC model had significantly reduced turnover by allowing clinics to offer improved benefits and salaries.

State officials outlined several strategies adopted by clinics to address ongoing staffing challenges. For example, officials in four states reported that a primary strategy employed by clinics throughout the demonstration was to offer enhanced salaries, noting that the offer was possible only because of increased funding under the demonstration's PPS. One official noted that "one of the CCBHCs had been able to be more successful because they finally realized that they had to pay more. And once that clinic did, they all started paying more. The CCBHCs were stuck in the [pre-demonstration] mentality that 'we can't afford to pay it' but realized that, in order to staff up as quickly as necessary and stay staffed up, we're going to have to increase salaries. And because of the PPS, they did." Officials highlighted several other strategies that clinics have used to combat staffing challenges in the second demonstration year, including the following:

-

Relying on telehealth to fill gaps and extend staff reach while seeking additional staff (in progress reports, three clinics mentioned the addition of telehealth positions to their staff in order to address staffing challenges, especially telepsychiatry).

-

Engaging recruiters to advertise to and hire professionals from out of state.

-

Engaging the state's credentialing board to share job announcements with all credentialed providers in the state.

3. What Training have CCBHC Staff Received?

All clinics reported that, in the past 12 months, they provided at least one of the types of staff training required by the CCBHC criteria. In DY2, all clinics (n = 66) had provided training in the past 12 months in risk assessment, suicide prevention, and suicide response, and nearly all had provided training in evidence-based and trauma-informed care (95 percent, n = 63) and cultural competency (91 percent, n = 60) (Table III.1). For most of the training types listed in Table III.1, the proportion of CCBHCs that reported providing the training in the DY2 progress report was similar to that in DY1, except for risk assessment, suicide prevention, suicide response, and person-centered and family-centered care, all of which increased by more than a few percentage points.

| TABLE III.1. CCBHC Staff Training in Required and Other Topics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic of Training | CCBHCs that Provided Training in Past 12 Months, March 2018 (DY1) |

CCBHCs that Provided Training in Past 12 Months, March 2019 (DY2) |

||

| N | % | N | % | |

| Required by CCBHC certification criteria | ||||

| Risk assessment, suicide prevention, and suicide response | 62 | 93 | 66 | 100 |

| Evidence-based and trauma-informed care | 61 | 91 | 63 | 95 |

| Cultural competency training to address diversity within the organization's service population | 59 | 88 | 60 | 91 |

| The role of family and peers in the delivery of care | 52 | 78 | 51 | 77 |

| Person and family-centered care | 51 | 76 | 56 | 85 |

| Recovery-oriented care | 51 | 76 | 51 | 77 |

| Primary and behavioral health care integration | 51 | 76 | 52 | 79 |

| Other training (not required by CCBHC certification criteria) | ||||

| Other (see Table III.2) | 40 | 60 | 38 | 58 |

| Any training listed abovea | 66 | 99 | 66 | 100 |

| No training | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total CCBHCs | 67 | 100 | 66 | 100 |

| SOURCES: CCBHC Annual Progress Report Demonstration Year 1 and Year 2 data collected by Mathematica and the RAND Corporation, March 2018 and March 2019. NOTES: See Appendix Table A.4 for state-level findings. The proportion of clinics that provided each type of training varied across states to some extent, but the proportion within each state was relatively consistent from March 2018 to March 2019, except for in New Jersey, where it appeared that a larger proportion of clinics delivered various types of training in 2019 compared with 2018.

|

||||

Clinics reported that they provided a diverse range of non-required "other" trainings. In DY2, the most commonly reported non-required trainings included (Table III.2) motivational interviewing (an evidence-based practice [EBP] included in the CCBHC criteria) (18 percent of CCBHCs, n = 12); training focused on serving veterans and "military culture" (14 percent, n = 9); and training in two other EBPs, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (9 percent, n = 6) and MAT (8 percent, n = 5). Clinics delivered training in these most commonly delivered non-required topics in the previous year, though at lower rates except for training in serving veterans and "military culture," which 22 percent of clinics (n = 15) provided as of DY1, a decrease of 8 percentage points from DY1 to DY2. Finally, 5 percent of clinics (n = 3) offered training in disaster preparedness and response in DY1 while no clinics reported offering such training in DY2.

| TABLE III.2. CCBHC Staff Training in Non-Required "Other" Topics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic of "Other" Training | CCBHCs that Provided "Other" Training, March 2018 (DY1) |

CCBHCs that Provided "Other" Training, March 2019 (DY2) |

||

| N | % | N | % | |

| Motivational interviewinga | 7 | 10 | 12 | 18 |

| Serving veterans and "military culture" | 15 | 22 | 9 | 14 |

| CBTa | 6 | 9 | 6 | 9 |

| MATa | 3 | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| Ethics | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| DBTa | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Trauma-informed care | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| Serving LGBTQ individuals | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Disaster preparedness and response training | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Total CCBHCs | 67 | 100 | 66 | 100 |

| SOURCE: CCBHC Annual Progress Report Demonstration Year 1 and Year 2 data collected by Mathematica and the RAND Corporation, March 2018 and March 2019. NOTE:

|

||||

States provided ongoing support for CCBHC staff training as the demonstration was implemented. In preparation for and throughout the demonstration's implementation, all states developed structured networks for regular communication with their CCBHCs to identify gaps in knowledge and provide formal and informal training and support activities. State officials viewed such efforts as essential in identifying and responding to emerging training needs.

In the demonstration's first year, officials from all states reported that they held regular meetings with CCBHCs during the early stages of implementation to identify and address CCBHC training and technical assistance needs. As one official stated, "Training topics have covered the entirety of the CCBHC project." Officials described state-led trainings for CCBHC clinical and administrative staff in the following topics:

-

CCBHC certification requirements.

-

Best practices such as trauma-informed care and motivational interviewing.

-

Serving special populations such as children, high school students, or veterans.

-

Regulations regarding licensing for clinicians, including peer specialists.

-

PPS.

-

Billing, quality measure reporting, cost-reporting (for example, Pennsylvania required CCBHCs to complete a test run of their cost reports six months into the first demonstration year to ensure that clinic administrative staff would be able to complete the forms for the official deadline at the end of 12 months).

In the second demonstration year, officials reported that much of the training offered by states and clinics took place during the initial stages of the demonstration, noting that, by the second year, states exhibited less focus on formalized training. One state official mentioned feedback from clinics as a primary impetus for tapering training, remarking that "clinics have been giving the state a lot of feedback that they are 'trained out' when the state asks if they want more. They had to do an enormous amount of staff training in the first year to satisfy the criteria and now they're burned out on training. Because of that feedback, we ourselves as a state have been focusing on exploring what it takes to change practice and what could we be implementing rather than continuing to throw required training at [the CCBHCs]." Officials in two other states commented that, even though their states had reduced the number of training opportunities offered to CCBHCs and clinic staff, state demonstration leadership have continued to identify and alert clinic leadership to external training opportunities for their staff.

B. Access to Care

The certification criteria specify that CCBHCs must provide accessible care, including 24-hour crisis management services; engage consumers quickly through prompt intake services; and treat all consumers, regardless of their ability to pay. This section summarizes states' projections for the number of individuals to be served by the demonstration and describes the activities that states and CCBHCs have undertaken to expand access to care.

1. How many Medicaid (including dually eligible) Beneficiaries did CCBHCs Expect to Serve in the First Demonstration Year, and How Many were Served?

In DY1, officials in all but two of the demonstration states expected that, during the demonstration's first year, CCBHCs would serve the number of consumers as originally projected. State officials in New Jersey and Oregon reported in DY1 that, based on the lower-than-expected number of consumers that CCBHCs served in the first two quarters of the demonstration, the number of consumers served during the demonstration's first year would likely be lower than originally envisioned. Table III.3 summarizes states' projections at the beginning of the demonstration, the projected changes at the demonstration's mid-point (2018), and, drawing on interviews with state officials in 2019, actual beneficiaries served in the first demonstration year. While states generally reported that clinics were on track to serve expected or fewer than expected numbers of consumers, in interviews some states reported that certain clinics experienced higher than anticipated volume which stretched resources and staff.

| TABLE III.3. Projected and Actual CCBHC DY1 Enrollment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | State Population (in millions) |

Number of CCBHCs | DY1--Total Projected CCBHC Consumers to Receive CCBHC Services (all pay sources) |

DY1--Projected CCBHC Consumers Who Were Medicaid Beneficiariesa |

Actual Number of Consumers Served in DY1 |

| Minnesota | 5.52 | 6 | 17,600 | 15,000 | 20,000b (15,000 Medicaid) |

| Missouri | 6.09 | 15 | 127,083 | 87,284 | 86,002 (55,362 Medicaid) |

| Nevada | 2.94 | 3c | 7,305 | 5,844c | 2,312 Medicaidd |

| New Jersey | 8.94 | 7 | 79,782 | 50,882 | 79,800 (9,500 Medicaid)e |

| New York | 19.75 | 13 | 40,000 | 32,000 | 49,301f |

| Oklahoma | 3.92 | 3 | 23,076 | 11,077 | 16,836f |

| Oregon | 4.09 | 12 | 61,700 | 50,000 | 52,911 (32,859 Medicaid) |

| Pennsylvania | 12.80 | 7 | 24,800 | 17,800 | 19,190f |

| SOURCE: Table 5 in Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics Demonstration Program, Report to Congress, 2017. Mathematica/RAND obtained information for the "Changes to Projected Total CCBHC Consumers" during interviews with state officials in March 2018 and for actual Medicaid beneficiaries during interviews with state officials in March 2019. NOTES:

|

|||||

2. What Steps have the CCBHCs and DCOs Taken to Increase Access to Care?

CCBHCs have worked to make services more convenient and tailored to the needs of specific populations. According to state officials, one of the most common ways clinics have enhanced access to care is to institute open-access scheduling, or same-day scheduling, which is a scheduling method that allows all clients to receive an appointment on the day they request one. Officials in five states mentioned that most or all CCBHCs in their state have now adopted open-access scheduling. One state official in Nevada noted that CCBHCs instituted open-access scheduling because "the clinics acknowledge that it is important to meet the client in a moment of need and be able to start to establish services so that the client doesn't leave and never come back." State officials pointed to several other positive effects of open-access scheduling, such as the elimination of wait lists and a reduction in the burden on other external community resources. As one official in Missouri remarked, "People are able to have same-day access in areas where that has never before been possible, and in turn the access reduces the burden on hospitals, emergency departments, and law enforcement. People getting into CCBHC services quickly is a big deal."

|

CCBHC Spotlight: Availability and Accessibility of Services: "Meet the Client Where They're At" |

||

|---|---|---|

|