Printer Friendly Version in PDF Format (5 PDF pages)

ABSTRACT

This Issue Brief represents the finding of a white paper prepared by RTI under funding from ASPE. The analysis included a programs scan of policy initiatives in 21 states and individual interviews with academics, federal experts, state officials and individual providers.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization. This report was completed and submitted on October 2018.

Background

Between 1999 and 2014, the rate of opioid use disorder (OUD) among women who gave birth at United States hospitals more than quadrupled during 1999 to 2014.[1] This rise in OUD in pregnant women corresponds with an escalation in the prevalence of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS), increasing nearly seven-fold between 2000 and 2014.[2] Among women entering treatment for substance use disorder (SUD)--which includes but is not limited to OUD--approximately 70% have children.[3] I n recent years, clinicians and policymakers have become increasingly interested in supporting family-centered OUD treatment approaches that provide comprehensive services to pregnant and parenting women and their family members.

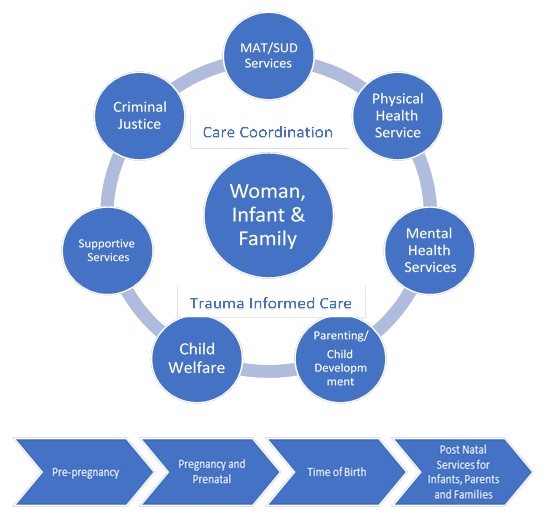

| EXHIBIT 1. Program Framework |

|---|

|

Family-Centered Medication-Assisted Treatment

Family-centered treatment programs recognize women's roles as primary caregivers and provide services for women, their children, fathers, and other family members. Services are delivered during pregnancy for women who are pregnant and ideally continue up to one year after delivery, and even longer in order to help support women in recovery. Clinical services include evidence-based treatment such as Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) as well as a range of physical health, mental health, and SUD services. Family-centered care is also comprehensive and emphasizes linkages with non-clinical support services such as housing, transportation, employment, and child care.

Challenges to Expanding Access to Family-Centered Treatment

In order to reduce barriers and expand access to OUD treatment for pregnant and parenting women, policymakers face several challenges.

Workforce Capacity: Many state policy officials report shortages across all types of addiction treatment professionals, which they attributed to insufficient training for clinical and non-clinical professionals in addiction medicine and to limited applicant pools.

Funding Concerns: Insufficient block grant funding for pregnant and parenting women has raised concerns about the availability of SUD services, particularly inpatient residential care, in future years. Additionally, limited sustainability of new funding opportunities for the opioid epidemic has left some providers reluctant to expand and experiment with new service delivery models.

Coverage Challenges: According to policy officials and providers, private and public insurance programs do not typically reimburse for case management or support services provided by non-clinical professionals such as peer recovery coaches, patient navigators, lactation consultants, and child life specialists.

Provider Reluctance to Provide MAT: Despite guidelines[4, 5, 6] indicating that MAT is the recommended best practice in treating pregnant women, state policy officials asserted that provider resistance to provide MAT points to ongoing stigma and inhibits states' efforts to expand access.

Fear of Criminal Prosecution: In some states substance use by pregnant women has to be reported by providers to law enforcement and can even be used as grounds for civil commitment. The practice of characterizing OUD as criminal behavior can prevent women from seeking treatment and re-enforces stigma, according to providers and academic researchers.

|

Family-Centered Treatment is Effective

|

Opportunity for Policymakers

-

Many states and programs focus on treatment during pregnancy but do not extend services to women after delivery, despite treatment in the postpartum period being critical to prevent relapse. Some states like New Mexico used Medicaid 1115 waivers, others like Texas used state dollars to fund services for postpartum women in recovery.

-

While services for infants and younger children are incorporated into many comprehensive treatment models, few state programs offer care to older children and partners. There is a need for additional programming for adolescent children, fathers, co-parents, and other key family members.

-

Research examining integrated primary care/OUD treatment models that improve outcomes for women, partners, and children would help advance the implementation of family-centered programs nationwide.

-

Alternative payment models, like the recently announced MOM model,[6] could allow providers greater flexibility in designing programs that support case managers, peer recovery specialists, and other non-clinical support professionals and services deemed essential to facilitating family-centered care.

-

Flexible funding streams would allow states to allocate resources to their highest priority substance use issues, such as methamphetamine misuse, and not only OUD among women.

-

Innovative practices for integrating housing supports into treatment programs could help improve recovery outcomes for pregnant and postpartum women.

-

Provider education, especially around the use of MAT as a best practice for treating pregnant and parenting women with OUD, is fundamental to improving access to services. Mentorship of newly waivered physicians has proven successful to increase their comfort in treating pregnant women.

-

Formal and informal partnerships among state agencies that serve this population can address many of the barriers to consistent treatment that social risk factors, like housing, food, and transportation insecurity can present.

Endnotes

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. August 10, 2018. Opioid Use Disorder Documented at Delivery Hospitalization--United States, 1999-2014. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/pdfs/mm6731a1-H.pdf.

-

Patrick S.W. (2018). Testimony before the United States Senate, U.S. Senate Committee on Health Education, Labor and Pensions.

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2007) Family-Centered Treatment for Women with Substance Use Disorders--History, Key Elements and Challenges. Retrieved from: https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/family_treatment_paper508v.pdf.

-

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2012). Opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 524. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 119(5): 1070-1076. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22525931.

-

American Society of Addiction Medicine. (2015). The American Society of Addiction Medicine national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. Chevy Chase, MD: Author. Retrieved from: https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/practice-support/guidelines-and-consensus-docs/asam-national-practice-guideline-supplement.pdf?sfvrsn=24.

-

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Innovation Center, Maternal Opioid Use (MOM) Model. From https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/maternal-opioid-misuse-model/.

FAMILY-CENTERED MEDICATION-ASSISTED TREATMENT

This report was prepared under contract #HHSP233201600021I between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy (DALTCP) and the Research Triangle Institute. For additional information about this subject, you can visit the DALTCP home page at http://aspe.hhs.gov/office-disability-aging-and-long-term-care-policy-daltcp or contact the ASPE Project Officer, Kristina West, at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201. Her e-mail addresses is: Kristina.West@hhs.gov.

Reports Available

Expanding Access to Family-Centered Medication-Assisted Treatment Issue Brief

- HTML: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/expanding-access-family-centered-medication-assisted-treatment-issue-brief

- PDF: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/expanding-access-family-centered-medication-assisted-treatment-issue-brief

State Policy Levers for Expanding Family-Centered Medication Assisted Treatment