M. Susan Ridgely , Rosalie Liccardo Pacula , and M. Audrey Burnam

RAND Corporation

This report was prepared under contract #HHSP23320095649WC between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy (DALTCP) and the RAND Corporation. For additional information about this subject, you can visit the DALTCP home page at http://aspe.hhs.gov/_/office_specific/daltcp.cfm or contact the ASPE Project Officer, John Drabek, at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201. His e-mail address is: John.Drabek@hhs.gov.

The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization.

Preface

The Interim Final Rules (IFR) implementing the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008 went into effect on July 1, 2010. This report describes the findings from short-term studies commissioned by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and undertaken by the RAND Corporation. These studies were focused on two issues in the IFR, where HHS felt that further research would be useful in informing the implementation of the MHPAEA. The two issues are the use of “non-quantitative treatment limitations” (NQTLs) by self-insured employers, insurers, health plans and managed behavioral health organizations and the identification of a “scope of services” in behavioral health to which parity applies.

The findings reported here on NQTLs are based on interviews with managed behavioral health industry experts, deliberations of an Expert Panel convened by the HHS Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, consultations between ASPE and RAND staff, and a discussion with state regulators in Oregon, which is the only state that has adopted a statute with NQTL provisions similar to the MHPAEA.

The findings on “scope of services” reported here are based on descriptive analyses of linked plan and utilization data from the MarketScan Health Benefits Database for the year 2008. The original purpose of analyzing these data was to generate a model of annualized per member per month (PMPM) total cost so that the model could be used to assess the extent to which these costs were sensitive to alternative scenarios for coverage of three types of “intermediate” behavioral health services (i.e., intensive outpatient visits, partial hospitalization, and residential treatment). Careful scrutiny of the data, however, revealed there was insufficient variation in spending on these key services across health plans in the MarketScan database, which would be necessary in order for us to build a reliable model. However, the linked data provide insights into the provision of these intermediate services by health insurance plans prior to the implementation of the MHPAEA. The findings are helpful in considering the effect of applying a parity requirement to the scope of services that health plans cover.

Executive Summary

This paper describes analyses commissioned by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to inform the implementation of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008. This law generally requires that mental health and substance use disorder (MH/SUD) insurance benefits be comparable to the benefits for medical and surgical care. Coverage of MH/SUD services has often been more limited than most other health services with, for example, more restrictions on the number of outpatient visits or inpatient days covered and higher co-pay requirements.

The MHPAEA requires group health plans and group health insurance issuers to ensure that financial requirements (e.g., co-payments, deductibles) and treatment limitations (e.g., visit limits) applicable to MH/SUD benefits are no more restrictive than the predominant financial requirements or treatment limitations applied to substantially all medical-surgical benefits. The Interim Final Rules (IFR) implementing the MHPAEA clarified that there are other types of treatment limits, beyond those listed as examples in the statute, to which the principles of parity should apply. These other types of treatment limits are referred to in the IFR as “non-quantitative treatment limitations” (NQTLs) and are defined as limits that are not expressed numerically but otherwise limit the scope or duration of benefits. NQTLs are further described as including the broad array of health care management policies and practices designed to contain costs of health care, including: medical necessity definitions and criteria (claims not covered unless care is deemed medically necessary); utilization management (UM) practices (preauthorization, concurrent review, retrospective review to determine medical necessity); formulary design in the pharmacy benefit (tiers of medications with differing co-pays/maximum days filled); and provider network management (credentialing and inclusion/exclusion of providers from networks, establishing fees for in-network providers, setting “usual, customary and reasonable” fees for out-of-network providers).

To better understand how health plans and issuers use these NQTLs to manage access to care, HHS commissioned a study to gather information from health plans and practitioners. This paper summarizes interviews with managed behavioral health industry experts and the discussion by a panel comprised of well-known researchers and practitioners with clinical expertise in MH/SUD treatment as well as general medical treatment, experience in developing evidence-based practice guidelines, and knowledge of how plans use NQTLs.

The information provided by managed behavioral health industry experts and the deliberations of the Technical Expert Panel were focused on how NQTLs are used by plans and insurers to manage MH/SUD benefits and any clinical justifications for variations in how NQTLs apply to MH/SUD benefits compared to medical benefits. The Expert Panel discussed three main categories of NQTLs: medical necessity definitions and criteria, UM practices, and provider network management. The panel discussed a number of processes, strategies, and evidentiary standards that they considered justifiable considerations for plans and insurers to use in establishing NQTLs for MH/SUD and medical-surgical benefits. The justifiable considerations identified by the panel included evidence of clinical efficacy, diagnostic uncertainties, unexplained rising costs, availability of alternative treatments with different costs, variation in provider qualifications and credentialing standards, high utilization relative to benchmarks, high practice variation, inconsistent adherence to practice guidelines, whether care is experimental or investigational, and geographic variation in availability of providers. The panel also discussed how the standard in the IFR requires that these considerations be applied in a comparable way to MH/SUD benefits and medical-surgical benefits in determining how a plan or insurer will apply an NQTL. Furthermore, the panel discussed situations in which the outcome of applying these considerations in a comparable way may justifiably result in a different application of an NQTL to MH/SUD benefits compared to medical-surgical benefits.

Another issue identified by HHS as meriting additional research was the implications of the MHPAEA for the scope of services that health plans must offer. The IFR requested public comment on this question. To inform policy-making on this topic, HHS commissioned research into current coverage of intermediate level services for MH/SUD by health plans. In behavioral health care, as in general medical care, there is a continuum of services that lie between inpatient and outpatient care that have been shown to effectively treat some MH/SUD, and in some cases do so more cost-effectively than inpatient care. Examples of such intermediate forms of behavioral health care include non-hospital residential services, partial hospitalization services, and intensive outpatient services including case management and some forms of psychosocial rehabilitation. Although such services are provided in employer plans, there has been little quantitative information available on the extent to which these services are covered and utilized.

This paper includes an analysis of the Thomson Reuters MarketScan data that offers several insights into the extent to which employer plans included coverage for these services prior to the implementation of the MHPAEA and at what cost. Descriptive analyses showed that the average cost per member per month (PMPM) for all plan-provided health care was found to be $268. Almost all of these costs are for medical-surgical services and related prescription drugs. Behavioral health services accounted for $12, or 4.6% of total PMPM costs. Furthermore, the vast majority of the cost for behavioral health was for behavioral health prescriptions ($7.46).

Intermediate behavioral health services -- those that lie between inpatient and outpatient care -- were provided by employer plans in 2008, although the results differed greatly for each service. Examples of such intermediate services are non-hospital residential treatment, partial hospitalization, and intensive outpatient treatment. Almost all of the employer-based plans had claims for intensive outpatient treatment (98%), most had claims for partial hospitalization (59%), but few had claims for non-hospital residential treatment (18%). Together the additional cost of providing these three services represented a very small fraction of the average total plan cost in 2008 ($2.40 PMPM or 0.9%).

These findings on current levels of coverage of these intermediate services are helpful in considering the effect of applying a parity requirement to the scope of services that plans cover. They indicate that these types of services are already covered to some degree. However, in order to estimate the effect of imposing a parity requirement further research is needed to estimate the degree to which these current coverage levels of intermediate services may change to meet a parity standard.

1. Introduction

In general, parity requires that mental health and substance use disorder (MH/SUD) insurance benefits be comparable to and no more restrictive than the benefits for medical-surgical care. Coverage of MH/SUD services has been more limited than most other health services. Restrictions have included annual or lifetime limits on the number of provider visits or inpatient days, annual or lifetime caps on spending for MH/SUD services, or differential co-pay requirements for MH/SUD services. The net effect of these limitations has been generally less coverage and greater patient financial risk for care of these illnesses.

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008

The 2008 enactment of the MHPAEA represents a new era for coverage of behavioral health conditions. While the law has some exclusions, it is substantially more comprehensive than the previous federal parity law1 and considerably stronger than most state parity laws. The Act requires that financial requirements and treatment limitations for group health plans, including out-of-network provider coverage for treatment for mental and substance use disorders, be no more restrictive than those for medical-surgical services. The new federal law does not pre-empt more restrictive state parity requirements but does extend parity to self-insured plans that are exempt from state regulation. It also extends parity beyond benefits for treating mental health disorders, to include benefits for treating substance use disorders.

1. Mental Health Parity Act, PL 104-204 (1996).

The Interim Final Rules (IFR)

On February 2, 2010 the Departments of Labor, Treasury and Health and Human Services published Interim Final Rules (IFR) in the Federal Register.2 The IFR and the accompanying guidance were meant to help consumers, self-insured employers, insurers, health plans and managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) (among other stakeholders) understand the provisions of the MHPAEA and to guide the implementation.

Non-Quantitative Treatment Limitations

The IFR forbid self-insured employers and health plans from employing more restrictive “quantitative treatment limitations” (such as visit limitations for treatment of mental and substance use disorders) and also required that the use of “non-quantitative limitations” (including differential formulary design, standards for admitting providers to the network, or differential medical necessity criteria) be no more stringent in limiting the scope or duration of benefits for behavioral health treatment relative to medical treatment.

Non-quantitative treatment limitations (NQTLs) refer to the broad array of health care management policies and practices designed to contain costs of health care, including medical necessity definitions and criteria (claims not covered unless care is deemed medically necessary); utilization management (UM) practices (preauthorization, concurrent review, retrospective review to determine medical necessity), formulary design in the pharmacy benefit (tiers of medications with differing co-pays/maximum days filled), and provider network management (credentialing and inclusion/exclusion of providers from networks; establishing fees for in-network providers; setting usual, customary, and reasonable fees for out-of-network providers).

The IFR specifically requires that the “processes, strategies, evidentiary standards and other factors used to apply NQTLs to MH/SUD benefits in a classification have to be comparable to and applied no more stringently than the processes, strategies, evidentiary standards and other factors used to apply to medical-surgical benefits in the same classification.” The regulations also acknowledge that there may be different clinical standards used in making these determinations -- including evidence-based practice guidelines. The regulations do not necessarily require equivalence in results when applying parity requirements to NQTLs, only comparable processes, strategies, and standards in determining application of NQTSs.

After publication of the IFR questions remain regarding application of the NQTL provisions and also how the MHPAEA applies to scope of services.

Scope of Services

In behavioral health -- like other areas of medical care -- there is a continuum of services that lie between inpatient and outpatient care that have been shown to effectively treat some MH/SUDs, and in some cases do so more cost-effectively than inpatient care. Examples of such intermediate forms of behavioral health care include non-hospital residential services, partial hospitalization services, and intensive outpatient services including case management and some forms of psychosocial rehabilitation. The “scope of services” issue concerns the extent to which the MHPAEA requires a full rangeof MH/SUD services (i.e., a continuum of care). The IFR did not specify requirements regarding application of parity to these intermediate services.

Given the unanswered questions in the IFR with regard to NQTLs and scope of services, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) sought a contractor to perform short-term studies in order to better understand the likely impact of regulation.

ASPE asked RAND to design and conduct studies to address the following policy questions:

What should be the criteria for parity in NQTLs?

What is the impact of applying parity to the scope of services covered by health plans and insurers, focusing on various levels of coverage of intermediate services?

The purpose of this Project Memorandum is to summarize the findings from these two studies.

2. 26 CFR Part 54 (Treasury-IRS); 29 CFR Part 2590 (Labor-EBSA) and 45 CFR Part 146 (HHS-CMS).

2. NON-QUANTITATIVE TREATMENT LIMITATIONS (NQTLs)

In the original scope of work, RAND was asked to provide background materials, attend, and write up a summary of the deliberations of an Expert Panel on NQTLs to be convened by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). However, at ASPE’s request, we revised the scope of work to develop a strategy that would enable the Expert Panel convened for this project to focus on clarifying issues related to the implementation of parity in NQTLs. In the revised scope of work, we expanded the NQTL study to encompass three areas of activity: (1) consulting with industry representatives on their experiences with implementation of the IFR to date; (2) working with the Expert Panel to create additional specific examples that could be included in future guidance with regard to NQTLs; and (3) understanding the experience of Oregon regulators who had to address NQTLs in the implementation of the Oregon parity law -- the only state law in the country that specifically addresses NQTLs.

Consultations with Industry Representatives

RAND interviewed several industry representatives, and in this section we summarize their perceptions of the parity legislation and regulations, including their concerns. Industry representatives reported that implementation of parity regulations may have challenging and far-reaching business consequences for the MBHO industry. Some sectors of the industry report that they are facing much more complicated implementation issues than others. The implementation of parity regulations is seen as fairly straightforward for organizations that are integrated medical and behavioral health managed care plans.

Our interviews identified special issues that may confront the MBHO carve-out business. Comparisons with general medical plan features can become very complex, because hundreds of different general medical plans can be involved. The MBHO can employ a strategy that makes comparisons and adjustments on a plan-by-plan basis, which imposes greater complexity of management (and increases administrative costs). A key concern is that if the MBHO adopts a more centralized management strategy, carve-out clients (the clients in this case are the self-insured employer or the major medical plan) may find their behavioral health benefit management misaligned with its corresponding major medical plan. Because the behavioral health carve-out is often not the “at-risk” plan, but instead is a provider of administrative services only, it can make recommendations, but the client ultimately determines key features of NQTLs. Some MBHOs, through an era of mergers and acquisitions, have become very large organizations with a multiple and diverse book of business; consequently, according to some industry representatives, implementation of the IFR is a complex undertaking, which begins with investment of considerable time and resources to collect the information needed to evaluate compliance, let alone respond. In addition to these general observations, these industry representatives offered the following specific observations on types of NQTLs.

Medical Necessity Definitions and Criteria

Medical necessity definitions provide a broad framework for guiding the more specific standards, guidelines, or decision support protocols that these organizations use to make coverage decisions. In October 2000, the Board of the Trustees of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) endorsed the statement of the American Medical Association (AMA), which defined medical necessity as “services or products that a prudent physician would provide to a patient for the purpose of preventing, diagnosing, or treating an illness, injury, or its symptoms in a manner that is: (1) in accordance with generally accepted standards of medical practice; (2) clinically appropriate in terms of type, frequency, extent, site, and duration; and (3) not primarily for the convenience of the patient, physician, or other health care provider.”3 The medical necessity definitions used by the organizations with whom we spoke were identical or closely corresponded to this definition, but sometimes had an additional cost-related consideration (e.g., “not more costly than alternative services and at least as likely to produce equivalent therapeutic or diagnostic results…”). The NQTL regulations stimulated these organizations to undertake efforts to document and compare their behavioral health and general medical benefit definitions, but they reported that this resulted in no or little change in those definitions.

To translate the definitions into tools that can guide decisions to authorize or deny care, these organizations invariably use a committee structure, composed of both in-house and external clinical experts, to review existing guidelines, research evidence and benchmarks, and to develop specific coverage recommendations and criteria, which are updated on an annual basis, and approved at the top levels of the organization. These criteria are used by care managers in making coverage decisions as part of the UM processes (e.g., to preauthorize care, or approve care for reimbursement as part of concurrent or retrospective review.) Several organizations mentioned that, while care managers can approve care, a supervising physician must review all denials of care. Several organizations mentioned testing consistency of application of criteria among care managers. Some organizations also described use of information systems to scan for potential problem areas (e.g., high geographic or facility variation in utilization patterns for certain diagnoses or treatments, with those areas then becoming a topic for committee review.) Leaders from each organization with whom we spoke had reviewed and determined that their processes of developing medical necessity criteria were comparable to the processes used for general medical care.

Specific decision tools and algorithms used to apply medical necessity criteria on a case-by-case basis have traditionally been considered proprietary and they were not shared with us. We note, though, that these may not stay protected for long. The statute and the IFR require that the criteria used for medical necessity determinations for behavioral health benefits be provided to participants, beneficiaries, or contracting providers upon request. One organization has decided to go a step beyond the requirements -- it has begun routinely providing the relevant criteria to participants and providers when care is denied or partially denied. This industry leader said that, so far, this information about specific reasons for denial seems to be well received.

These organizations are not yet seeing appeals of medical necessity decisions specifically related to MHPAEA parity, although they are watching broader trends carefully. They have had some inquiries from providers who are under the impression that any use of NQTLs is prohibited under the IFR.

A few examples were given of services that are not covered because they are not considered medically necessary: (1) “wilderness” programs for youth -- because of no evidence of effectiveness and the lack of clinically credentialed staff; and (2) Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) for autism, because it is considered educational rather than medical. In addition, industry leaders mentioned limited coverage for psychological testing, because while it is clinically appropriate to rule out certain diagnoses, it is also a service that is subject to abuse. Some industry representatives suggested that these services may serve useful social functions but are not evidence-based behavioral health treatments.

One industry leader discussed the challenges of managing the quality and costs of outpatient psychotherapy, which composes the bulk of outpatient care. This respondent argued that outpatient psychotherapy does not have a parallel in medical care because: (1) existing guidelines are not specific; (2) clinician training and standards, especially for masters-level therapists, are diverse, so therapists may not have appropriate skills; and (3) there is no way to know what goes on in psychotherapy (e.g., what specific therapeutic approaches and techniques are used).

3. American Medical Association Policy Statement, H-320.953 -- Definitions of "Screening" and "Medical Necessity" (CMS Rep. 13, I-98; Modified: Res. 703, A-03).

Utilization Management (UM) Practices

UM refers to the policies and protocols that define when and for what types of services preauthorization, concurrent review,and retrospective review are utilized. The review provides the opportunity for medical necessity criteria to be applied. Thus, the review may result in denial of coverage for all or some portion of care, or authorize coverage for an alternative to the requested care. In addition, preauthorization and concurrent review may delay care -- if participants and providers wait on the outcome of the review -- or discourage care due to the “hassle” factor.4

The industry leaders we interviewed reported that their organizations review and update UM practices in the same manner as updating of medical necessity criteria, and use the same or similar committee process. UM practices are also updated in response to federal and state regulatory requirements. Industry representatives said that the factors they use to drive the nature of review processes were intended to prevent “overuse” and “misuse” of services. For example, one organization cited Wennberg’s5 four factors: (1) regional variation; (2) underuse of effective care; (3) misuse of preference-sensitive care; and (4) overuse of supply-sensitive care. Another mentioned practice variation, above benchmark use, and evidence of inconsistent adherence to evidence-based guidelines. Cost containment is also relevant, as reflected in comments that they attend to: unexplainable rise in costs of a service, and patterns of use of high cost services relative to commonly available alternatives.

Comparison of behavioral health UM practices to those in general medical care required these organizations to develop a cross-walk between classes of services, and make a comparison. Some organizations were still in the process of collecting information and making changes on a plan-by-plan basis. One organization mentioned that they have sometimes changed from UM to a limit in benefit design, to be consistent with the medical plan.

The industry representatives told us that a few issues stood out as being particularly ambiguous with respect to comparison across behavioral health and general medical UM practice:

-

According to the industry, outpatient behavioral health care has some unique features and does not cross-walk well with outpatient medical care. The potential for misuse and overuse is perceived to be high relative to, for example, visits with a primary medical care provider or a cardiologist. One industry leader suggested that psychotherapy was probably more like occupational, physical, and speech therapy, in its potential for misuse and overuse.

-

They also said that intermediate levels of care (e.g., intensive outpatient and partial hospitalization) are also challenging to cross-walk, and plans have made different decisions about whether to place these alongside outpatient or inpatient medical care. Industry leaders reported that as a result behavioral health UM practices have become more varied across plans than prior to the IFR. Some industry leaders noted that guidance from the government that would allow a more uniform approach to behavioral health UM practice would be welcome.

-

For inpatient care, some medical plans rely on DRG-based standards, for example, applying retrospective review or capping the benefit when DRG amounts are exceeded. Behavioral health inpatient care is not subject to Medicare DRG payments (too variable within diagnostic groups), so no equivalent method exists.

The IFR has already led to UM practice changes for these organizations. For outpatient behavioral health care, several industry leaders told us that the pass-through number (that is, the number of visits that are allowed prior to review) has changed from a somewhat arbitrary number (e.g., 2, 8, 10, or 20), to a number based on the statistical distribution of visits (e.g., 1 or 2 standard deviations above mean visits, sometimes calculated within diagnosis). This has had the effect of making the pass-through number larger, and also preserving a more unified approach across medical plans served by a particular MBHO.

Some organization representatives told us that pre-certification of outpatient care, and preauthorization of inpatient care has been, or is in the process of being, phased out. One organization is replacing inpatient preauthorization with “pre-notification.” Another is replacing inpatient prior authorization with intensive concurrent review.

4. Koike A, KlapR, Unutzer J (2000). “Utilization management in a large managed behavioral health organization.” Psychiatric Services, 51: 621-626.

5. Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Skinner JS (2002).“Geography and the debate over Medicare reform.” Health Affairs, published ahead of print February 13, 2002, doi:10.1377/hlthaff.w2.96. [Available athttp://content.healthaffairs.org/content/early/2002/02/13/hlthaff.w2.96/suppl/DC1]

Provider Network Management

Provider network management refers to processes for credentialing and including/ excluding providers from networks, the establishment of fees for in-network providers, and setting usual, customary and reasonable (UCR) fees for out-of-network providers.

These organizations reported using standard credentialing checks to decide which providers to include in their networks. Some leaders mentioned excluding certain subspecialties (for example, specialty providers of ABA for autism), and reported doing ongoing evaluations of network providers. One industry leader noted that a problem for all organizations is a shortage of psychiatrists in many geographic regions (especially in rural and frontier areas), and that they work hard to credential and include as many psychiatrists as apply. Another noted that exclusion of individual providers was done only on the basis of “egregious” quality issues. All have reviewed their provider network management practices in response to the IFR, and a number of issues have emerged.

Some organizations report having special requirements for masters-level therapists to have post-degree supervised clinical experience (2 or 3 years), because many masters programs do not offer this training and state licensing requirements vary widely for masters-level clinicians. There is no parallel with general medical network providers and they do not require this for psychiatrists or PhD-level psychologists, whose licensing does require supervised clinical experience.

Some organizations discussed challenges related to setting and/or negotiating in-network provider fees using similar approaches to medical plans. For example, some medical plans may use Medicare fee standards (some multiple of Medicare fees), but not all do. Providers sometimes have expectations that their fees should be increased to be equivalent to medical providers, or should be automatically adjusted along with those of medical providers. The industry perspective is that these providers fail to recognize, in the words of one respondent, that “the markets are different.”

According to the industry representatives, establishing UCR fees for out-of-network providers is another challenging issue. Medical plans rely on data obtained from companies that collect and analyze large numbers of claims from multiple payers, but information on psychotherapy is not available from these companies. One organization uses their own in-network data to establish UCR fees; another mentioned less systematic collection of information about UCR fees in local markets.

In response to the IFR, one organization has dropped their provider network inclusion requirement of supervised experience for some clinical subspecialties, while two others have not (on the basis that the requirement is defensible).

Expert Panel

On March 3, 2011, SAMHSA convened a panel of experts to provide substantive and technical input on issues related to the use of NQTLs. The Expert Panel members represented a broad range of knowledge and expertise including clinical expertise in MH/SUD treatment, experience in developing evidence-based practice guidelines, and experience use of NQTLs in their practice. In attendance at the meeting were the Expert Panelists, the moderators (Howard Goldman and Audrey Burnam), and SAMHSA, ASPE, and National Institute of Mental Health staff. In addition, a number of federal agency staff participated in all or parts of the meeting (see Appendix 1). RAND provided a background paper for panelists that included some of the observations made by industry representatives.

Over the course of the meeting, we first solicited feedback from the panelists about how to evaluate parity in medical necessity definitions and processes for establishing specific clinical guidelines and criteria. We then asked the panelists to discuss parity in UM practices. Finally, the panelists weighed in on parity in processes used in provider network management. That discussion is summarized in bullet points below:

Medical Necessity Definitions and Criteria

Medical necessity definitions are broad, and plans may adopt APA/AMA definitions, which are comparable across behavioral health and general medical care. Plans may also include in their definitions a consideration of costs (e.g., to provide efficient or cost-effective care). The panel view was that, broadly, medical necessity definitions that included cost-effectiveness considerations could be clinically appropriate.

Specific guidelines and criteria that plans adopt to guide medical necessity determinations are based on processes of expert review of existing guidelines, empirical literature, and other information. The panel discussed the types of information that might be relevant to the adoption of specific criteria: clinical efficacy, uncertainty, high potential costs, provider qualifications, practice variation. It could be reasonable to treat behavioral health conditions differently with respect to medical necessity determinations when the evidence base supports differences. The panel discussed specific examples, including fail-first and step-care requirements, and some types of procedures/services that are often considered unnecessary, to illustrate situations in which medical necessity determinations would or would not be clinically appropriate and meet parity requirements.

Utilization Management Practices

Some of the possible rationales discussed by the panel that plans use to justify differential management include the following: utilization above national benchmarks, costly relative to commonly used alternative services or levels of care; unexplained practice variation in the use of services or levels of care; unexplained rising cost trend (e.g., Suboxone), evidence of inconsistent adherence to established practice guidelines, identified gaps in care (e.g., low rates of post-hospital follow-up care); and possible experimental or investigational procedures (e.g., rapid opiate detox).

Some panelists suggested that, especially in substance abuse treatment, the potential high variation in practice (in treatments received for those with similar substance abuse problems) that is not solely determined by provider training or qualifications suggests that differential management may be appropriate.

Differential concurrent review may be appropriate when you have a provider type that is not licensed by the state -- this should be the same across the behavioral health and general medical benefit -- although the effect will be felt more on substance abuse providers.

Provider Network Management Practices

The panel discussed how behavioral health providers (in particular some types of substance abuse treatment counselors and psychotherapists) do not have consistent training or credentialing standards across subfields, and there is also considerable variation in licensing standards for these types of providers across states. This discussion suggested that it may be clinically appropriate for plans to have additional criteria (such as experience requirements) for inclusion in networks.

The panel did not feel qualified to offer specific opinions on data sources for setting network fees and UCR fees for out-of-network providers, but generally agreed with the principle that use of market data to set fees should be similar across behavioral health and other medical providers (for example, basing fees on a multiple of Medicare fees).

The relationship between fees and network adequacy is an important parity consideration.

Network adequacy is routinely reported by plans using indicators such as access, waiting times, availability of certain specialty care (and others). The panel recognized that network adequacy is influenced by availability (e.g., rural areas may have limited availability of certain kinds of specialists).

If fees offered for behavioral health providers are so low that network adequacy is poor, relative to medical network adequacy, then this would raise an issue of parity.

There was considerable discussion about exclusion of primary care providers in behavioral health networks, because primary care providers often treat behavioral health conditions, and there is growing evidence of effectiveness of some primary care based treatment models. ASPE staff noted that they recognized the importance of this issue, but suggested that the complexity of reimbursement issues were beyond the scope of the panel’s charge.

The Expert Panel agreed on the following examples for regulators use in providing additional guidance to the field -- but also raised a number of questions.

Medical Necessity Determinations

Stepped care requirements can be in violation of parity if these are applied in ways that are not clinically appropriate for behavioral health conditions. Routinely requiring outpatient treatment before covering inpatient or residential treatment for behavioral health conditions (for example, for treatment of substance use disorders) would be inequitable, since such requirements are not routinely applied for general medical conditions. But stepped care requirements can be clinically appropriate for some patients (e.g., with uncomplicated and less severe substance use disorder) when stepped care is consistent with accepted clinical guidelines.

There is an analogue in general medical care -- treating pneumonia in a frail, elderly person who lives alone. Treatment for pneumonia can often be ambulatory, but not in every case. The question would be, is the inpatient admission clinically justified? A “blanket rule” against behavioral health inpatient admissions should not be allowed.

Medical necessity determinations are guided by specific clinical guidelines and/or criteria that plans adopt and update based on processes of review and evaluation of clinical evidence, and on other information such as costs, practice variation, etc. If these processes and criteria hold behavioral health services to higher clinical evidence standards than general medical services, then medical necessity determinations are not equitable and do not meet parity requirements.

Cost and efficiency considerations, per se, do not violate parity. For example, medical necessity criteria may result in reimbursement for the less costly but denial of the more costly of two alternative treatments that are equally effective and safe. If such cost and efficiency considerations apply to behavioral health medical necessity determinations, however, they must also apply for general medical determinations by the medical plan.

Routinely reimbursing for self-management and educational services for chronic general medical conditions (such as diabetes) but denying these kinds of services for severe and persistent mental illness is inequitable and does not meet parity requirements.

Clinical evidence supports use of certain kinds of self-management and educational services in both cases. If clinical evidence were similarly evaluated, and patient education and self-management services were differentially reimbursed based on level of evidence of clinical appropriateness, then different medical necessity determinations would be justified.

“Fail-first” requirements may be clinically appropriate. For example, medical necessity determinations may deny reimbursement for a brand name antidepressant medication until the patient first tries and fails a generic antidepressant medication. If fail-first requirements such as these are applied in the behavioral health benefit, however, they must also be applied in a comparable fashion in the medical benefit.

There are some instances in which different fail-first requirements would be clinically appropriate. For example, if there is a laboratory test that can be administered to help determine which of several alternative medications to use for a particular medical condition -- and there is no such test to help decide which antidepressant to use -- that could be a reasonable basis on which to require a “fail-first” policy for generic antidepressants but not for medications for the medical condition, because the laboratory findings would determine the choice of medication in the latter case.

A fail-first requirement for oral antipsychotic medication before reimbursement of injectablemedication may not be clinically appropriate for some patients, because of adherence challenges with oral antipsychotic medications. Parity requirements imply that there should not be fail-first requirements such as these on the behavioral health side (e.g., fail-first requirements that disregard preferred medication choices based on adherence considerations) unless there are also such limits on the general medical side.

Utilization Management

Outpatient psychotherapy is often subject to plan review after a certain number of visits, to authorize reimbursement for further visits. According to some panelists, psychotherapy is an example within the behavioral health field where there is a high degree of uncertainty about the nature of the problem (diagnosis), about what treatment will work, about what type of provider is required, and with high variability in quality and duration of treatment. These considerations suggest that different UM practices for outpatient psychotherapy may be justified relative to outpatient visits for many general medical conditions.

The panel noted that psychotherapy is a specific procedure (not a class of benefits like outpatient services) and so comparability of UM should be evaluated at the level of the procedure, not the benefit level. Panelists pointed out that there are comparable procedures in medical care that are characterized by clinical uncertainty and practice variability, for example, physical therapy. Parity requirements imply that if psychotherapy is subject to a particular UM practice, similar procedures (e.g., physical therapy) in the medical benefit should not have a less intense level of UM.

Panelists pointed out that diagnostic uncertainties and high variability in treatment/provider choices exist for some behavioral health conditions, but are also found for other general medical conditions (e.g., lower back pain). If certain behavioral health diagnoses (e.g., adjustment disorders, substance abuse) are selected for differential and more aggressive UM practice than others, such differences would be justified under parity regulations only if these were comparable to or less restrictive than UM practices for comparable general medical conditions.

Requiring prior authorization for all outpatient behavioral health services is not clinically appropriate, as this may unnecessarily delay clinically appropriate services, and inhibit access to appropriate clinical services. Such prior authorization practices for behavioral health care would meet parity requirements only if similar prior authorization is required for all medical outpatient care.

Plans may require prior authorization or conduct concurrent review of targeted behavioral health services or procedures, for example, psychological testing. This may be justified on the basis of clinical appropriateness, but in order to meet parity requirements, similar considerations should result in similar UM management practices for medical services.

Plans may utilize concurrent review for inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations that are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis, and retrospective review for general medical hospitalizations that are reimbursed as a total fee based on DRGs. Differences in UM practice in this case are justified because DRG-based fees are not established for psychiatric hospitalizations. DRG-based reimbursement creates incentives for the hospital to actively manage utilization, but in the absence of incentives for the hospital to control costs, concurrent UM by plans is clinically appropriate.

For general medical hospitalizations that are not reimbursed based on DRGs, parity would require similar or no more stringent UM practices for behavioral health inpatient care than for these types of general medical inpatient care.

Plans may require prior authorization for medications like Suboxone (used to treat opiate addiction), if this practice is justified by clinical appropriateness considerations, such as risk for abuse, that are similarly applied to other medications (e.g., Oxycontin). If psychiatric or addiction medications like Suboxone require prior authorization based on different standards than other medications, then parity requirements would not be met.

Network Management

According to the panelists, the number of different kinds of behavioral health providers with hugely different levels and types of training -- which is both more confusing and less regulated than in the general medical arena -- suggests that differential management may be permissible.

But panelists noted that there are areas of general medical care where there is similar variability in provider training -- such as in foot care (surgeons and podiatrists), pain management (anesthesia nurses, anesthesiologists, acupuncturists) and physical medicine (physiatrists, physical therapists and occupational therapists).

Plans may have network admission criteria that include experience requirements (e.g., 2-3 years of post-degree supervised clinical experience) for certain types of behavioral health providers. These can be justified when training and licensing requirements are highly variable across states and do not consistently require relevant and appropriate supervised clinical experience.

Experience requirements should be clinically reasonable given the type of clinical practice the provider engages in, and no more stringent for behavioral health providers than the experience requirements included in licensure for general medical providers.

Similar network adequacy metrics should apply to both behavioral provider networks and general medical networks.

It would not be equitable, for instance, if there were egregious variations in access rates, wait times, availability of specialists, etc.

Differences across geographic regions and urban/rural areas in network adequacy are also expected because of differential availability of providers.

Fee standards should be arrived at using the same type of process but the result does not have to be the same (i.e., fees for providers may be under-market for both behavioral health and general medical providers).

It would be inequitable to have general medical fees tied to Medicare but not tie behavioral health fees to Medicare. If Medicare-based fee standards are not available for some types of behavioral health providers/services, then parity implies that, whatever market standards are used, behavioral health providers/services are not differentially and more dramatically underpriced relative to their market than general medical providers/services.

Consultation with Oregon Regulators

Oregon is the only state that has adopted a statute with NQTL provisions similar to the MHPAEA.6 The Oregon Insurance Division (OID) is the office with responsibility for regulating health plans. We contacted staff at the OID and arranged for an interview about their experience in regulating NQTLs -- providing them with questions in advance.

After some initial “back and forth” with health plans and a few informal enforcement actions when the Oregon parity statute was first being implemented (for example, denying an attempt by one plan to require a treatment plan after eight outpatient visits), one of the health plans “threatened to take [OID] to a hearing" on the NQTL section of their statute. An internal review of the statutory language forestalled any further enforcement actions.

The OID staff reported the following with regard to their interpretation of NQTLs:

If the application of a differential policy seems reasonable -- with regard to the number and type of services to which it applies -- they would allow it.

They would allow differences (for example, in cost sharing and UM) for psychiatrists -- as long as all specialists were treated the same by the health plan.

They also mentioned that they had begun deferring to the federal IFR and guidance (that is, deeming health plans compliant with the Oregon rules if they are in compliance with the IFR).

6. McConnell JK, GastSHN, Ridgely MS, Wallace N, Jacuzzi N, Rieckmann T, McFarland BH, McCarty D (2012). “Behavioral health insurance parity: Does Oregon’s experience presage the national experience with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act?”American Journal of Psychiatry, 169: 31-38.

Summary and Discussion

Here we summarize and discuss the work we conducted to assist ASPE in clarifying implementation of the IFR with regard to the requirement that NQTLs be applied no more stringently for behavioral health care relative to medical care. In particular, we note that the IRF requires that the “processes, strategies, evidentiary standards, and other factors used to apply NQTLs to MH/SUD benefits in a classification have to be comparable to and applied no more stringently than the processes, strategies, evidentiary standards and other factors used to apply to medical-surgical benefits in the same classification.”

Consultations with MBHO industry leaders provided insight into processes the industry uses to establish and apply NQTLs, and into industry views on challenges and uncertainties that arise in implementation of NQTL parity regulations. In the area of medical necessity definitions andformulary design, industry representatives did not raise significant concerns or challenges related to implementation. In the area of UM practices, however, industry representatives provided examples of lack of clarity in how to cross-walk and make comparisons between behavioral health and medical care in both outpatient and inpatient benefit classifications, as well as lack of clarity in how to consider intermediate levels of care in behavioral health (such as intensive outpatient and partial hospitalization). In the area of provider network management, some representatives expressed lack of clarity about whether supervised clinical experience qualifications for certain types of behavioral health providers to be included in networks were allowable under NQTL regulations, and representatives consistently raised the issue of not being able to use the same methods in setting fees for behavioral health providers as medical providers, because comparable data are not available to do so. In addition to the issues above, industry leaders whose MBHO included a significant carve-out business raised a broader implementation issue. From the perspective of these industry leaders, the task of coordinating with numerous medical plans to evaluate and implement parity was highly challenging.

Based on our discussions with industry leaders, we conclude that providing further examples that clarify NQTL regulatory guidance, particularly in the areas of UM practices, and provider network management, could facilitate understanding of and compliance with the regulations. Further clarifying examples are unlikely, however, to alleviate the concerns of carve-out MBHOs that arise from the burden of coordination with numerous medical plans managed by other organizations.

The panel of clinical experts convened by SAMHSA discussed processes, strategies and evidentiary standards relevant to evaluating parity in NQTLs, and provided examples of situations in which, in the view of the panel, NQTLs would and would not be in accordance with parity regulations. The discussion consistently reflected panelists’ views of NQTLs as a means to promote both clinically appropriate and cost efficient care. The panel discussed a number of processes, strategies and evidentiary standards -- related to both of these goals -- that were justifiable considerations for establishing medical necessity criteria, UM practices, formulary design, and network management practices. Considerations mentioned by the panel included: evidence for clinical efficacy, diagnostic uncertainties, unexplained rising costs, the availability of alternative treatments with different costs, variation in provider qualifications and credentialing standards, high utilization relative to benchmarks, high practice variation, inconsistent adherence to practice guidelines, identified gaps in care, whether care is experimental or investigational, and geographic variation in availability of providers.

Examples offered by the panel were drawn to show parallels between the kinds of clinical appropriateness and cost efficiency considerations used in management of both behavioral health and general medical care. If such considerations are applied consistently across management of behavioral health and general medical care, in the panel’s view, then the application of NQTLs meets parity regulations. While the panel focused on a number of examples in which the potential “uniqueness” of behavioral health care might make the comparison of behavioral health and other medical care NQTLs problematic, the discussion ultimately resulted in the identification of similar NQTL situations in medical care where comparisons could be drawn.

In conclusion, the Expert Panel meeting supported the view that parity of behavioral health care NQTLs with medical care NQTLs can be evaluated by comparing the processes, strategies, and evidentiary standards that are used to establish and apply the NQTLs. The specific examples provided by the panel should serve useful for clarifying the implementation of the NQTL regulations.

3. Scope of Services

As mentioned earlier, there are “intermediate” behavioral health services -- those that lie between inpatient and outpatient care. Examples of such intermediate services are non-hospital residential treatment, partial hospitalization, and intensive outpatient treatment. However, the IFR did not specify requirements regarding application of parity to these intermediate services. RAND was initially asked to construct an actuarial model of health insurance premiums that could be used to evaluate the impact of alternative levels of inclusion of these specific intermediate behavioral health services on health care costs.

A good actuarial model requires information on health plan characteristics (such as benefits and UM techniques) and enrollee population characteristics and therefore requires linked plan-utilization data. In consultation with ASPE, we chose to use the 2008 MarketScan database available through Thomson Reuters. Using these data we set out to build an actuarial model that could be used by ASPE to understand the impact of alternative levels of inclusion of intermediate behavioral health services on average total plan costs and premiums. However, as we began constructing indicators of intermediate service care utilization, and examining them as well as costs in statistical models, it became evident that an analysis employing a single year of data was insufficient for constructing a reliable model for two reasons: (1) the statistical model estimating average per member per month (PMPM) total plan costs was very sensitive to how utilization of intermediate services, particularly residential treatment, was represented in the model due to the sparseness of these data; and (2) with only a single year of data, we could not adequately control for unobserved factors influencing general health care utilization within each health plan. Nevertheless, descriptive analyses (reported below) provide a picture of the number of health plans providing these intermediate services prior to the implementation of the MHPAEA and the level of utilization of these services within these plans -- which is helpful in considering the effect of applying a parity requirement to the scope of services that health plans cover.

MarketScan Health Benefits Database

The MarketScan database provides linked claims data on over 5 million enrollees from 52 employers and 80 different health insurance carriers. The data include individuals with private insurance from across the United States. The data, obtained directly from large employers, include comprehensive claims information (inpatient, outpatient, pharmaceutical and behavioral carve-out information) on all employees who work for a firm, regardless of health plan or whether medical benefits are received from the same carrier as behavioral health benefits. MarketScanincludes plans offering very generous health benefits (e.g., large employers and union health and benefit plans), as well as more traditional plans and consumer-directed health plans. Thus the database provides us with a population of enrollees with unlimited access to behavioral health services and those with very limited access.

For a small subset (10%) of the claims and encounters databases (110 health plans in 2008), Thomson Reuters has added benefit plan design information, which they have created from plan booklets obtained from the employers providing the data. The booklets range in their level of detail and depth, so Thomson Reuters codes as much information as possible. Due to the variability in the quality and specificity of information, however, the health plan benefit data are not always complete; nor is it guaranteed that the same specific constructs are being measured precisely across plans. Despite these limitations, we believed useful information could be obtained with respect to general cost sharing requirements (deductibles, co-payments,co-insurance rates), limits, exclusions, and other plan aspects important for understanding the average cost of providing coverage for a plan.

We used the 2008 linked benefits claims and encounters databases to generate a plan-level database for conducting descriptive analyses of current coverage of behavioral health spending and assess the feasibility for estimating an econometric model of the average medical cost (PMPM cost), which would form the backbone of an actuarial model. Although the 2008 database listed identifiers for 110 plans, two plans in the benefits database had no actual enrollees, four plans consistently reported missing information for all plan benefit design measures, and another lacked information on key benefit variables (co-payment and deductibles) relevant for examining PMPM costs (which when combined with an administrative loading factor determine premiums). Thus our starting analytic sample consisted of general plan benefit information for 103 plans.

Limited project resources and the high cost of the data precluded us from obtaining additional years of data to augment the sample. Because it is known that medical costs and medical practices vary substantially across geographic regions, additional information regarding cost of providing particular services can be gleaned by disaggregated the 103 plans down to the region level. Four principal regions are specified in the data (Northeast, Southeast, Midwest and West), but a “national” option was also provided, generating five possible values for this region indicator and a maximum of 432 plan-by-region observations (before missing values are considered). This relatively large number of plan-by-region observations emerges because the overwhelming majority of the 103 original plans (87.4%, n= 90) operated in more than one region.7

A problem with disaggregating plans, however, is that it can artificially generate “small” plans out of what are actually large plans. By that we mean that a relatively small share of a plan’s enrollee’s might be serviced in one region, while the bulk of the plan’s enrollees are covered in one or two other regions and yet calculations of average cost are based on the number of enrollees in a given region and not the overall plan. If an intermediate service used infrequently, such as residential treatment, is used by an enrollee in the artificially-generated “small” plan, then it would give the appearance of a much higher impact on total spending than what was truly experienced by the health plan. To ensure our analysis was not affected by the disaggregation of plans across regions, we used as our final analytic sample a version of the data that removed plans that had fewer than 50 people in one region if 85% or more of the enrollees were located in another region. This sample had 290 region plans represented in the data. Although some person-level data were not used in creating the analytic sample, all 103 plans are represented.

7. Seven of the 13 plans operating in one region operated only in the West, four operated in the Midwest, and two operated in the South. None of the plans indicating only one region listed that region as national.

Variable Construction and Descriptive Statistics

We are interested in understanding whether parity requirements with respect to specific intermediate services could generate excessive costs to the health plan, indicated by higher average PMPM medical costs. To understand this, we need to consider and account for a variety of variables that can also influence average PMPM medical costs, including plan and enrollee characteristics, plan benefit design, and general utilization. A description of the construction of each of these measures and some simple descriptive statistics based on the total sample and final analysis sample is provided below.

Enrollee and Health Plan Characteristics

The main demographic variables we could construct from enrollee information (aggregated up to the region level) were the following: percent male, percent children (i.e., <18 years of age versus 19-65 population), and the Charlson-DeyoIndex, which is a weighted index of 17 chronic illnesses (identified through ICD-9 codes) that are likely to generate inpatient hospitalization within the coming year (based on Deyo et al., 1992).8

The MarketScan database did not include public insurers or Medigap plans. Additional plan characteristics we could construct from the data included the size of the plan (measured by enrollees within the region), and the type of the plan (e.g., HMO, PPO, POS, consumer-directed health plan, etc.). Descriptive statistics for these variables for the full 432 plans and our final analytic sample of 290 plans are provided in Table 1.

The most noticeable consequence of moving from the full sample to the analysis sample is the sizeable decrease in the percent of small plans, from 38.4% to 8.3%. The reductions in small plans show up in other statistics as well. Differences in means and maximum values between the full sample (n=432) and the final analytic sample (n=290) shows that there is an important reduction in variance within our analytic sample in the Charlson-Deyo index. The maximum value falls from 0.667 from the full sample to just 0.166 in the analytic sample (n=290). By construction the maximum score possible for this index is 33, based on the weighting of the 17 diagnoses represented. In our encounter (individual level) data, we do observe some fairly high patient values. However, when these values are averaged over total plan enrollment, the typical value for the plan is much closer to the mean value observed across all individual encounters of care (0.023). One consequence is that the variance in this index across plans is extremely limited, and not likely to capture the plan heterogeneity in chronicity of patients that we had hoped it would. This reduced variance in the index across plans is an indication that we may not have adequately captured important differences in general health care utilization across plans.9

TABLE 1. Enrollee and Plan Characteristics for the Full Sample (Panel A) and Final Analytic Sample (Panel B)

N | Mean | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANEL A -- Full Sample | ||||

| Enrollee Characteristics | ||||

| % Male | 432 | 47.9% | 0 | 100% |

| % Children (Age <18) | 432 | 22.3% | 0 | 62.5% |

| Charlson-Deyo Index | 432 | 0.023 | 0 | 0.667 |

| Plan Characteristics | ||||

| Small Plan (<100 full-year enrollees in region) | 432 | 38.4% | 0 | 100% |

| Medium Plan (100 - 4,999 full-year enrollees in region) | 432 | 38.3% | 0 | 100% |

| Large Plan (5,000 or more full-year enrollees in region) | 432 | 23.4% | 0 | 100% |

| % HMO | 432 | 14.8% | 0 | 100% |

| % PPO (capitated and non-capitated) | 432 | 55.1% | 0 | 100% |

| % Exclusive Provider Org or Point of Service Plan | 432 | 9.3% | 0 | 100% |

| % Consumer-Directed or Comprehensive Plans | 432 | 16.4% | 0 | 100% |

| PANEL B -- Analysis Sample | ||||

| Enrollee Characteristics | ||||

| % Male | 290 | 48.7% | 19.7% | 75.0% |

| % Children (Age <18) | 290 | 24.9% | 0 | 39.2% |

| Charlson-Deyo Index | 290 | 0.024 | 0 | 0.166 |

| Plan Characteristics | ||||

| Small Plan (<100 full-year enrollees in region) | 290 | 8.3% | 0 | 100% |

| Medium Plan (100 - 4,999 full-year enrollees in region) | 290 | 56.9% | 0 | 100% |

| Large Plan (5,000 or more full-year enrollees in region) | 290 | 34.8% | 0 | 100% |

| % HMO | 290 | 10.7% | 0 | 100% |

| % PPO (capitated and non-capitated) | 290 | 61.0% | 0 | 100% |

| % Exclusive Provider Org or Point of Service Plan | 290 | 7.6% | 0 | 100% |

| % Consumer-Directed or Comprehensive Plans | 290 | 16.9% | 0 | 100% |

Plan benefit design can influence utilization of health care services by influencing the relative cost of the services to patients (through co-payments, deductibles and management techniques). Plan characteristics can proxy both the extent to which care is managed in order to control costs as well as the likely risk pool. In addition to the obvious types of measures (type of plan, region of operation, plan size), we were able to consider several benefit measures available through the benefit plan database. However, many of the potentially important benefit measures for parity were missing data or lacked clarity in terms of what benefit applied. Appendix Table A1 in Appendix 2 lists the plan benefits we had hoped to consider and the number of plans in our linked data set (out of 103) that actually contained this information. As the table highlights, very few of the actual benefits are systematically recorded for most plans, making the plan information far less useful than we originally anticipated. Thus, the only measures we were able to consider for analysis were the following: family deductible; medical co-insurance rate for outpatient visit; constructed measure of equality in inpatient co-insurance rates; constructed measure of equality in outpatient co-insurance rates; number of NQTLs; and behavioral health carve-out indicator. We obtained the first two plan measures directly from the benefit database. We constructed the remaining four measures using various reported plan benefit information, as described in Appendix 2.Table 2 provides descriptive statistics of these variables for the full sample and our reduced analytic sample.

TABLE 2. Descriptive Statistics for Plan Benefit Characteristics and Measures

N | Mean | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANEL A -- Full Sample | ||||

| Average Family Deductible | 432 | $735.17 | 0 | $4,000 |

| Co-insurance -- outpatient visit (amount paid by plan) | 381 | 87.68% | 70% | 100% |

| Proportion of plans with equal co-insurance - inpatient | 413 | 40.8% | 0 | 100% |

| Proportion of plans with equal co-insurance - outpatient | 413 | 70.0% | 0 | 100% |

| Number of health plan NQTLs | 432 | 2.75 | 0 | 4 |

| Proportion of plans with behavioral health carve-out | 432 | 66.4% | 0 | 100% |

| PANEL B -- Analysis Sample | ||||

| Average Family Deductible | 290 | $843.22 | 0 | $4,000 |

| Co-insurance -- outpatient visit (amount paid by plan) | 261 | 86.6% | 70% | 100% |

| Proportion of plans with equal co-insurance - inpatient | 279 | 82.8% | 0 | 100% |

| Proportion of plans with equal co-insurance - outpatient | 279 | 76.0% | 0 | 100% |

| Number of health plan NQTLs | 290 | 2.78 | 0 | 4 |

| Proportion of plans with behavioral health carve-out | 290 | 85.2% | 0 | 100% |

Deyo R, Cherkin D, Ciol M (1992). “Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 45: 613-619.

We also considered capturing variance in general health care utilization through indicators representing the fraction of plan enrollees who were either: (a) current or past smokers, or (b) obese. However, given the high correlation of these behaviors with behavioral health care utilization, measurement of these values in the same year as behavioral health care utilization would result in significant colinearity.

Behavioral Health Service Setting Variables

There are a number of different indicators that can be used to identify a behavioral health claim occurring in one of the three intermediate care settings of interest, and no one indicator is consistently used by all the plans. We therefore applied rules across a multitude of indicators when we tried to identify residential treatment episodes (and length of stay), partial hospitalization and intensive outpatient visits (IOV) across plans.

Residential Treatment. Identification of individuals receiving treatment in a residential treatment setting involved a multi-step process. First, in the inpatient data we identified anyone receiving care in: (a) a residential substance abuse facility (STDPLAC = 55); (b) a psychiatric residential treatment center (STDPLAC = 56); or (c) general residential treatment center (STDPROV = 35). We removed from these claims those that also indicated that the service setting was an inpatient hospital setting (STDPLAC = 21 or 51 -- meaning general inpatient hospital or psychiatric inpatient hospital) unless the revenue code and procedure codes indicated that the care was non-hospital residential treatment.10Second, in the outpatient claims data we identified cases where additional outpatient type services were attached to an inpatient hospitalization, but these had not been flagged and aggregated with the inpatient claims by Thomson Reuters. These were identified in one of two ways: (a) the outpatient claim included an H-code indicating hospital or residential based treatment (H0017, H0018, or H0019); and (b) CPT codes indicated hospital based interactive psychotherapy (CPT codes in the range 90823-90829).

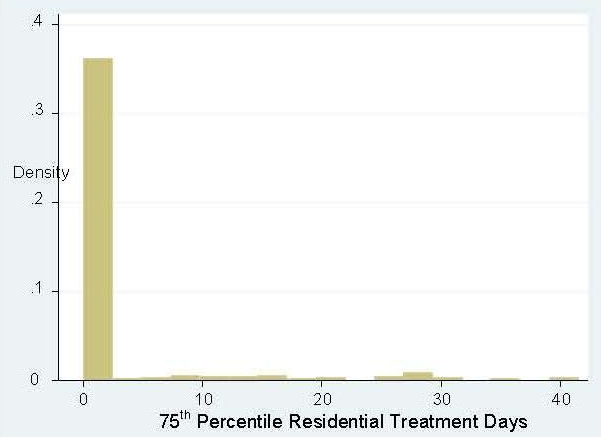

Applying these rules we identified approximately 2,050 residential treatment episodes in the data. While this represents a non-trivial number of residential treatment episodes, analytically what matters for our assessment of the effect on health plan costs is the distribution of these episodes across plans. Table 3 shows that fewer than 15% of the health plans in the full sample (n=52 out of 432) had any episodes involving residential treatment, and the mean number of episodes was very small (n=1). And while the proportion of plans with residential treatment claims is higher in our analytic sample (nearly 18%), this is due to our disproportionately dropping plans with zero claims. The mean number of residential treatment claims rises to just two in the analytic sample.

TABLE 3. Proportion of Plans Experiencing a Residential Treatment, Partial Hospitalization Visit or Intensive Outpatient Claim

| N | Mean | Mean # of Claims | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PANEL A -- Full Sample | |||

| Proportion of Plans with Residential Treatment Claim | 432 | 12.5% | 1 |

| Proportion of Plans with Partial Hospitalization Claim | 432 | 39.1% | 14 |

| Proportion of Plans with Intensive Outpatient Claim | 432 | 77.8% | 2,911 |

| PANEL B -- Analysis Sample | |||

| Proportion of Plans with Residential Treatment Claim | 290 | 17.9% | 2 |

| Proportion of Plans with Partial Hospitalization Claim | 290 | 56.9% | 21 |

| Proportion of Plans with Intensive Outpatient Claim | 290 | 98.3% | 4,333 |

Table 4 shows the distribution of claims across plans more explicitly. Thirteen of the 52 plans in our final analytic sample had just one residential treatment claim in 2008, and another 18 plans had five or fewer claims. Only 4.5% of all plans (n=13) had more than ten claims processed for residential treatment.

TABLE 4. Distribution of Plans by Number of Visits for Intermediate Services (n=290)

| Intermediate Service Claims | Number of Plans with Claims | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 - 5 | 6 - 10 | 11 - 20 | 21 - 50 | 51 - 75 | 75+ | |

| Residential Treatment | 238 | 13 | 18 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

| Partial Hospitalization | 125 | 27 | 28 | 23 | 24 | 50 | 11 | 18 |

| Intensive Outpatient Therapy | 5 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 23 | 11 | 236 |

As is clear from these tables, a claim for residential treatment is a rare event in MarketScan’s 2008 data. The relatively low number of claims coupled with the bunching of positive values at very low levels of visits across health plans will make identification of the effects of covering these services highly imprecise and possibly biased.

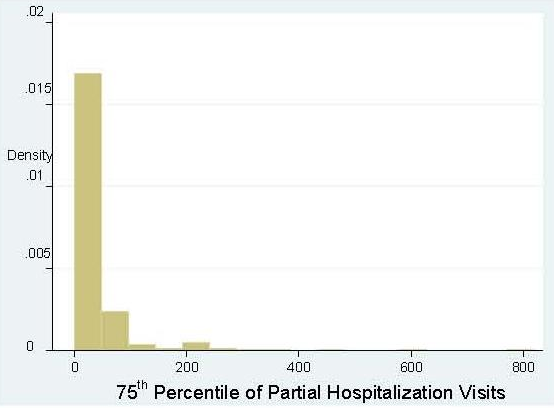

Partial Hospitalization Visits. There were relatively few cases of partial hospitalization in the inpatient claims data, but a few did exist and were easily identified through either a CPT code (90816-90822) or hospital revenue code (REVCODE = 912). Most of the claims involving partial hospitalization were in the outpatient data. These claims were identified again through procedure codes (CPT codes of 90816-90822) and H-codes (H0035).

Combined, we identified over 3,700 claims related to partial hospitalization in the inpatient and outpatient data. This is nearly twice the number of claims identified for residential treatment, and far more plans experienced at least one claim for partial hospitalization (as indicated in Table 3 and Table 4). Several plans experienced multiple claims for partial hospitalization and with longer episode length, increasing the variability in number of visits across plans.

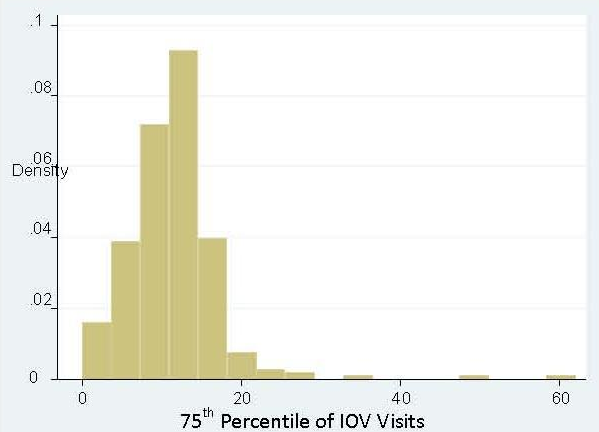

Intensive Outpatient Visits (IOV). Identification of IOV was based solely on information provided in the outpatient claims data. Identification of these cases was based on procedure codes (CPT-codes in the range of 90804-90815 or an H-code of H0015). Nearly 178,000 intensive outpatient claims were identified in the MarketScandata for 2008, with over 85% of health plans in our analytic database experiencing at least one claim. As shown in Table 3 (by the mean number of claims) and Table 4 (in terms of the distribution of number of visits), there are a large number of health plans that experienced multiple claims for intensive outpatient treatment. This is a far more common service being utilized across the health plans represented in MarketScan’s2008 data.

10. As revenue and procedure codes are used for reimbursement purposes, we have more confidence in these measures for indication of the type of care received then in the variable identifying the setting. This only affected six claims so even if they are improperly identified, it would not affect our results.

Average Spending Overall and By Service

The construction of annualized PMPM total health care costs is based on all payments made by the plan (or a plan subcontractor in the case of behavioral health carve-outs) for general medical care, behavioral health services, and pharmaceutical claims incurred for enrollees. We calculated PMPM annual costs by summing up all health-related costs to the person level, then aggregating persons within the plan to generate a total cost per plan. Average costs are constructed by dividing the total cost per plan by the total number of member months observed in the data (as not all individuals are enrolled over the entire year), which generates a monthly estimate that can be annualized by multiplying by 12.

Table 5 shows some descriptive statistics on the average health care costs across plans, as indicated by average PMPM costs in total, and broken out for selective health categories (medical, behavioral health, pharmaceutical) for our 432 plans (Panel A) and then for the 290 plans in our final analytic sample (Panel B). Again, in looking at changes in mean and maximum values across Panel A and B it is easy to see to how the removal of artificially created “small” plans impacts PMPM costs. Interestingly, the removal of these “small” plans reduces our average PMPM cost for behavioral health services overall, and in the case of residential treatment and partial hospitalization, the reduction in average PMPM costs is fairly substantial. However, the average total PMPM cost, PMPM medical cost, and non-behavioral health prescription costs are all higher in the analytic sample.

TABLE 5. Descriptive Statistics and Sample Sizes for PMPM Cost Estimates

| Variable | PANEL A: 432 Plans | PANEL B: 290 Plans | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Max | Plans with Non-Zero Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Max | Plans with Non-Zero Obs | |

| Total PMPM Cost | $251.63 | $203.30 | $1,659.81 | 381 | $268.49 | $125.70 | $734.70 | 290 |

| General Medical Center | ||||||||

| PMPM Medical | $186.15 | $160.79 | $1,570.91 | 381 | $200.90 | $84.27 | $518.98 | 290 |

| PMPM non-MH/SUD Prescription | $52.53 | $70.84 | $715.45 | 379 | $55.37 | $49.15 | $411.24 | 290 |

| Behavioral Health Care | ||||||||

| PMPM Total MH/SUD | $14.64 | $22.89 | $232.01 | 365 | $12.22 | $10.54 | $113.84 | 290 |