Prepared by:

Stephanie S. Teleki, Melony e.s. Sorbero, Lee Hilborne, Susan Lovejoy, Lily Bradley, Ateev Mehrotra, Cheryl l. Damberg

RAND Corporation

This product is part of the RAND Health working paper series.

RAND working papers are intended to share researchers’ latest findings

and to solicit additional peer review.

Prepared for:

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

This work was sponsored by ASPE and CMS under Task Order No. DHHSP2330000T under Contract No. 100-03-0019, for which Susan Bogasky served as the Project Officer.. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of ASPE or HHS.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge representatives of medical specialty societies and hospital associations who offered valuable information and insights about their experiences in developing performance measures and helping us to consider measures that may be applicable to the hospital outpatient setting. We thank Susan Bogasky, Project Officer, ASPE; Dr. Tom Valuck, Director, CMS Special Program Office for Value-Based Purchasing; and Dr. Julianne Howell, Project Coordinator Hospital VBP, CMS Special Program Office for Value-Based Purchasing for their review of this document and guidance on the project. We also appreciate the review of this document conducted by Drs. Allen Fremont and Steven Asch from RAND.

Preface

In response to a legislative mandate set forth in Section 109 (Title I) of the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (PL 109-432) (TRHCA), which established new requirements for reporting quality data for services paid under the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS), the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is currently working to identify performance measures that can be used to evaluate care provided to Medicare beneficiaries in the hospital outpatient setting. This mandate was motivated by recognized deficits in quality of care across all settings of care and ongoing concerns about the growth in utilization of services and costs.

In September 2006, the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), in collaboration with CMS, contracted with the RAND Corporation to identify the key reasons for visits and costs in the hospital outpatient setting, to review existing performance measures to assess their applicability to conditions evaluated as well as services/procedures and drugs/biologicals provided in the hospital outpatient setting, and to begin to identify measurement gaps. This report presents the results of this review.

This work was sponsored by ASPE and CMS under Task Order No. DHHSP2330000T under Contract No. 100-03-0019, for which Susan Bogasky served as the Project Officer.

Executive Summary

Background

A variety of studies have documented substantial deficiencies in the quality of care delivered across the United States (Asch et al., 2006; Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2000, 2001, 2005; Schuster et al., 1998; Wenger et al., 2003). While there are no comparable studies of the quality of care delivered in the hospital outpatient setting, pervasive deficits across the health system suggest similar problems likely exist, particularly since a large fraction of care delivered in this setting is ambulatory care for acute and chronic conditions where deficits in quality have been amply demonstrated.

In addition to potential quality of care deficits in the hospital outpatient setting, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has observed growth in the volume of services and costs for care delivered in this setting. In 2006, care provided to Medicare beneficiaries in the hospital outpatient setting accounted for 7 percent of total Medicare program spending (excluding beneficiary cost sharing) (MedPAC, 2007a), and overall spending nearly doubled between 1996 and 2006, reaching $31.6 billion (MedPAC, 2007b).

Under Section 109 of the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (TRHCA)1, Congress established new requirements for hospitals serving Medicare beneficiaries to report outpatient quality data to secure their full annual update to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) fee schedule. This new program, the Hospital Outpatient Quality Data Reporting Program (HOP QDRP), will begin in January 2008. The HOP QDRP builds on other CMS initiatives that are measuring and making transparent quality information and beginning to use incentives to promote high-quality and cost-effective care — key steps identified in the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Secretary’s “four cornerstones” for building a value-driven health care system (Leavitt, 2006).

A Scan of the Hospital Outpatient Landscape

The program requirements mandated under TRHCA have created a need for performance measures that CMS could use in the HOP QDRP. To assist CMS with the task of identifying both measurement opportunities and potential measures, the DHHS Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) in partnership with CMS issued a contract to the RAND Corporation in September 2006 to conduct an initial assessment of the hospital outpatient measurement landscape. RAND was asked to determine the leading conditions treated and services/procedures provided in the outpatient setting as a function of both volume and costs, and to identify existing performance measures that may be applicable to care provided in this setting as well as measurement gaps. As part of the environmental scan, RAND:

- Conducted an analysis of 2005 Medicare facility data for services paid through the hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) to determine the leading conditions and services/procedures;

- Scanned publicly available measures being used across a variety of settings to identify those that potentially apply to the care delivered in the hospital outpatient setting and to identify gaps, and

- Held discussions with medical specialty societies and hospital associations to determine whether they were aware of existing measures either being applied or that could be applied in the hospital outpatient setting, to learn about measure development work going on (to feed the measures pipeline), and to help identify measurement gaps.

For the purposes of our environmental scan, we defined the hospital outpatient setting as visits and/or services/procedures paid for under the Medicare OPPS. This care was further categorized for analyses and discussion in this report as either rendered in: (1) the ED, or (2) any other hospital-affiliated outpatient setting that is paid under OPPS (hereafter referred to as HOPS). We first classified services/procedures that obviously occur in the ED to the ED; all other services/procedures paid under the OPPS were classified as HOPS.

Key Findings

Analysis of Medicare OPPS Data

Based on our analysis of the Medicare OPPS facility data, in 2005 CMS was billed for 15,325,267 E&M encounters and 78,538,882 services/procedures in the HOPS. In the same year CMS was billed for 11,426,386 E&M encounters and 22,494,724 services/procedures in the ED. Overall, services/procedures represented a significant volume of the care provided in the hospital outpatient setting. More specifically, the top 20 most frequent services/procedures accounted for 58 percent of total services/procedures in the HOPS, and 94 percent of total services/procedures in the ED. Had 2007 payment rates been in effect in 2005, CMS would have paid $19.1 billion for services/procedures in the HOPS, and $1.7 billion for services/procedures in the ED2. The top 20 services/procedures, as a fraction of total costs based on application of 2007 payment rates, accounted for 44 percent of total dollars in the HOPS, and 83 percent of total dollars in the ED.

Of the conditions or services representing the greatest share of utilization and/or costs as a percentage of total use or spending, we find:

- General medical conditions are the most common reasons for visits in both the HOPS and ED.

- In the HOPS, general medical conditions (e.g., hypertension, aftercare for procedures, and specific and general symptoms like fever, dizziness) account for 35 percent of the care delivered, followed by oncology and neoplasia (13 percent); orthopedic conditions (10 percent) (e.g., back pain and arthritis); and endocrinology (7 percent) (e.g., diabetes).

- In the ED, general medical conditions (e.g., “symptoms,” injury like back sprains, lacerations) represented an even larger share of care delivered than in the HOPS (43 percent), followed by orthopedic conditions (17 percent).

- Ancillary services/ procedures, especially radiological, are the most common types of services/procedures provided in both the HOPS and ED settings.

- X-ray was found to be the most common service/procedure performed in both the HOPS and ED; however, it represents a larger proportion of the total in the ED (30 percent) as compared to the HOPS (12 percent).

- In the HOPS, other common services/procedures performed include Level III Pathology (5 percent) and electrocardiograms (4 percent).

- In the ED, electrocardiograms (16 percent) and Level II Drug Administration (9 percent) were found to be the most frequently performed services/procedures after X-ray.

- In the aggregate, many of the most common services/procedures also represent a substantial proportion of all costs in the hospital outpatient setting3. This finding is especially true of radiological services in both the HOPS and ED (X-ray, CT scans), and of X-ray in the ED (X-ray is one of the top two most frequent and most costly services provided in the ED). In the HOPS, the top two most costly services/procedures were cataract surgery (5 percent) and cardiac catheterization (5 percent), although neither of these procedures was found to be among the top 20 most frequently performed services/procedures in the HOPS. In the ED, the top two services/procedures as a function of total costs — CT scans (20 percent) and X-rays (17 percent) — accounted for 37 percent of total costs for services/procedures in the ED. Besides these areas, in the HOPS and ED, most single services/procedures were not found to account for a large proportion of total cost; however, services/procedures that account for even 1-2 percent of total spending in this setting represent significant spending.

- Imaging contrast material, blood products and cancer chemotherapy medications are among the most frequent drugs/biologicals used in both the HOPS and ED. In the ED, several thrombolytic agents are also among the most frequently used.

Scan of Existing Measures and Gaps

From our synthesis of information from the analysis of Medicare OPPS facility data, the scan of existing performance measures being applied in other settings, and discussions with medical specialty societies and hospital associations, we find:

Only a small number of measures specific for immediate application in the hospital outpatient setting currently exist or are in the pipeline. Ten measures comprise the initial hospital outpatient measure set to be used in HOP QDRP starting in January 2008; five pertain to care provided in the ED, and five assess performance related to diabetes, pneumonia, heart failure, and the use of antibiotics at time of surgery. Additionally, CMS has released 30 candidate measures for consideration that address a variety of conditions such as diabetes, fall risk, heart failure, depression, and stroke.

There is a large number of existing performance measures developed for use in other settings that are likely applicable to the care provided in the hospital outpatient setting. The scan of existing performance measures yielded approximately 700 measures that are publicly available and were developed for use in inpatient and ambulatory care settings, many of which are relevant to care delivered in the hospital outpatient setting. The majority of these publicly available, existing performance measures assess clinical effectiveness, primarily the underuse of services. Many are part of broad sets of ambulatory care measures (currently being applied at the physician, practice site, or medical group levels) that were developed by the American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI), the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), the Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) project, and the Cancer Quality – ASSIST (Assessing Sympoms Side Effects and Indicators of Supportive Treatment) Project. A number of these measures assess performance related to key reasons for visits to the HOPS (e.g., acute myocardial infarction (AMI), coronary artery disease (CAD), congestive heart failure (CHF), diabetes); cancer (especially breast, gastrointestinal, and prostate); and mental health. Additionally, measures developed by medical specialty societies assess care for specific diseases/conditions treated by that specialty (e.g., chronic kidney disease, cancer, polyp surveillance). A few measures assess care provided for cataract extraction, indications for cardiac catheterization, and treatment for cardiac arrhythmias. Apart from clinical effectiveness, there are existing measures of patient experience (CAHPS Clinician & Group, and Hospital Surveys) and patient safety (e.g., culture of safety, medication safety) that may be applicable to the hospital outpatient setting, though modifications in the measures would likely be required to make them directly applicable. While, our review focused only on publicly available measures, there are propriety measures in existence that may be relevant for assessing care provided in the hospital outpatient setting (e.g., RAND’s Quality Assessment (QA) Tools to assess clinical effectiveness, Symmetry’s Episode Treatment Groups (ETGs) to assess relative resource utilization).

Important Gaps Exist in Hospital Outpatient Services Measurement Areas. Despite the large number of existing measures identified that assess clinical effectiveness, there is an absence of measures that examine the appropriateness of care or use of services/procedures, such as imaging which has seen dramatic growth in utilization. Other measurement gaps include: ED care (especially measures to assess care provided to patients who have not yet been definitively diagnosed-- a common situation in the ED); some types of cancer care (e.g., lung cancer); specialty care; follow-up care; coordination-of-care/transitions-in-care; transmission of test results; outcomes; and episodes of care. In light of the performance dimensions identified by the IOM, there is also an absence of well-tested and validated measures of efficiency, equity, and timeliness of care.

Overall, while deficits in measures exist for some performance dimensions, there are a substantial number of existing measures that could either be directly applied or readily adapted for use in the hospital outpatient setting, particularly those addressing acute and chronic care provided in the ambulatory care setting, thus providing a near-term source of candidate measures for the HOP QDRP.

Considerations in Performance Measurement for the Hospital Outpatient Setting

There are several issues that would be valuable to consider in identifying candidate measurement areas and developing performance measures for the hospital outpatient setting, including:

- The type of care and services delivered in the hospital outpatient setting is not homogenous across hospitals or populations served. Services/procedures delivered in the hospital outpatient setting vary hospital-to-hospital as a function of size, location, service mix, and populations served. Because hospitals will vary in their ability to report on various performance measures, it will be important to include some measures that all hospitals can report on to enable cross comparisons of performance and to enhance the ability of all hospitals to participate.

- The problem of small numbers. A key consideration in selecting any performance measure is whether a provider has a sufficient number of events to score in a stable and reliable way. It is important to consider the number of events that occur at the hospital- level for any given condition, service/procedure, or use of drugs/biologicals, to determine whether it is even feasible to measure performance and how many hospitals could be expected to produce scores. The fact that the small numbers problem is compounded when attempting to stratify performance scores by subgroups of patients, such as by race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, and/or gender, also merits consideration.

- Existing measures specifications may need to be modified prior to applying in hospital outpatient setting. Existing measures are being applied in other settings, where the data to populate the measure differ (i.e., the codes used to pull administrative data) and the process of delivering the care may differ. These differences will need to be carefully reviewed to determine whether and how adjustments to the measures specifications are required if they are to be applied to the hospital outpatient setting.

- Physician engagement will be critical. Much of the care delivered by facilities in the hospital outpatient setting is dependant on the actions of physicians, both those practicing in the hospital outpatient setting and those in the community who are ordering services delivered in the HOPS. Therefore, it is important to engage these physicians in measurement and accountability requirements and to coordinate measurement efforts so that the measures for which physicians are individually held accountable are aligned with hospital measures.

- Alignment with other measurement efforts will minimize reporting burden and strengthen their performance improvement signals to providers. Continuing to coordinate measurement efforts with key organizations such as the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA), Ambulatory Quality Alliance (AQA), and the Joint Commission, as well as internally within CMS, to align measurement across settings of the health care system will be important to ensure that a consistent message is sent to all providers regardless of the setting(s) in which they provide care. This is a particularly critical undertaking given that the care delivered for a specific condition should not vary simply because of where a patient happens to present with that condition. To the extent possible, CMS could consider using the same measures to evaluate care in the hospital outpatient setting as are employed in other settings in which CMS tracks performance.

Next Steps for Consideration

Due to the limited resources for this project, the work completed here should be viewed as a preliminary assessment that requires follow-on work to fully flesh out how to apply existing performance measures in this setting and where the most important measurement gaps are for guiding the use of resources in the future.

As measurement efforts in the outpatient setting move forward, CMS could consider expanding on the work of this evaluation by:

- Conducting additional analyses of the OPPS data: Additional analyses using more detailed and complete OPPS data could refine the set of conditions, services/procedures, and drugs/biologicals that were identified in this study. This analysis could also include a broad set of clinical experts to help evaluate the care provided in the hospital outpatient setting to determine what the priorities should be for performance measurement and whether and how to group services and procedures for measurement. The analyses could address the limitations and suggested modifications noted in this study.

- Conducting a detailed mapping of measures to key areas of use and costs: Once more in-depth data analysis has occurred, a detailed mapping exercise between content areas and existing measures could determine measures that are ready to be used without modifications, and those that require modification and how they could be modified for use to assess performance at the hospital outpatient facility level. Once this work is completed, the candidate measures could be submitted to NQF for their review and endorsement.

- Determining where additional gaps exist and establish priorities for filling gaps: The information gathered from the in-depth data analyses and detailed measures mapping exercise could be used to identify gaps in measures. This review could consider the prioritization of conditions, services/procedures, and drugs/biologicals for determining future measures development work.

Glossary of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| ACOVE | Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders, a set of performance measures developed by RAND and UCLA |

| ACR | American College of Radiology |

| ABIM | American Board of Internal Medicine |

| ACC | American College of Cardiology |

| AGAI | American Gastroenterological Association Institute |

| AHRQ | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| AMA | American Medical Association |

| AMI | Acute myocardial infarction |

| APC | Ambulatory Payment Classification |

| APU | Annual payment update, and adjustment factor to CMS payment rates |

| AQA | Ambulatory Quality Alliance |

| ARBs | Angiostensin receptor blocker |

| ASC | Ambulatory surgical center |

| ASCO | American Society for Clinical Oncology |

| ASPE | Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation |

| ASSIST | Assessing Symptoms Side Effects and Indicators of Supportive Treatment |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CAHPS | Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, a suite of patient experience surveys |

| CHF | Congestive heart failure |

| CLFS | Clinical laboratory fee schedule |

| CLIA | Clinical laboratory improvement amendments |

| CMS | Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| CPT | Current Procedural Terminology |

| CT | Computed tomography scan |

| DRA | Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 |

| ED | Emergency department |

| E&M | Evaluation and management |

| EHR | Electronic health record |

| FY | Fiscal year |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HCAHPS | Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems |

| HCPCS | Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System |

| DHHS | Department of Health and Human Services |

| HOPS | Hospital Outpatient Setting (distinct from the ED) |

| HQA | Hospital Quality Alliance |

| ICD-9 | International Classification of Disease Version 9 |

| ICSI | Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement |

| IOM | Institute of Medicine |

| IT | Information technology |

| LVSD | Left ventricular systolic dysfunction |

| MedPAC | Medicare Payment Advisory Commission |

| MQSA | Mammography Quality Standards Act |

| NCQA | National Committee for Quality Assurance |

| NCCN | National Cancer Care Network |

| NQF | National Quality Forum |

| OFMQ | Oklahoma Foundation for Medical Quality |

| OPPS | Outpatient Prospective Payment System |

| P4P | Pay for performance |

| P4R | Pay for reporting |

| PCI | Percutaneous coronary intervention |

| PCPI | Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement, AMA |

| PQRI | Physician Quality Reporting Initiative |

| PSI | Patient Safety Indicators, a set of patient safety measures developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| QOPI | Quality Oncology Practice Initiative |

| RHQDAPU | Reporting Hospital Quality Data for Annual Payment Update, CMS’ quality reporting program for inpatient prospective payment hospitals |

| RUC | Relative Value Scale Update Committee |

| SCIP | Surgical Care Improvement Project |

| TRHCA | Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 |

I. Introduction

Background

Deficits in Quality of Care

A variety of studies have documented substantial deficiencies in the quality of care delivered across the United States (Asch et al., 2006; Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2000, 2001, 2005; Schuster et al., 1998; Wenger et al., 2003). In a national examination of the quality of care delivered to adult patients, McGlynn and colleagues found that patients received on average only about 55 percent of recommended care and that adherence to clinically recommended care varied widely across medical conditions (McGlynn et al., 2003). Wenger and colleagues found similar results for vulnerable elders living in community settings, with worse performance for geriatric conditions (Wenger et al., 2003). While there are no similar studies of the quality of care delivered in the hospital outpatient setting, pervasive deficits across the health system suggest similar problems likely exist in this setting, particularly since a large fraction of care delivered in the hospital outpatient setting is ambulatory care for acute and chronic conditions.

The Growth in Expenditures for Hospital Outpatient Care

In 2006, care provided to Medicare beneficiaries in the hospital outpatient setting accounted for 7 percent of total Medicare program spending (excluding beneficiary cost sharing), ranking it fourth (along with skilled nursing) after care provided in the inpatient setting (29 percent), by physicians (15 percent), and in other fee-for-service settings (i.e., hospice, rural health clinics) (13 percent) (MedPAC, 2007a). Overall spending by the Medicare program and beneficiaries on hospital outpatient services (excluding clinical laboratory services) nearly doubled between 1996 and 2006, reaching $31.6 billion (Figure 1.1) (MedPAC, 2007b). The CMS Office of the Actuary projects continued growth in total spending, averaging 10.4 percent per year from 2003 to 2008 (MedPAC, 2007b). A prospective payment system for hospital outpatient services (Outpatient Prospective Payment System [OPPS]) was implemented in August 2000 and the services paid under it represent approximately 90 percent of spending on all hospital outpatient services.

Figure 1.1. Spending on All Hospital Outpatient Services, 1996-2006 (MedPAC 2007)

Notes: Spending amounts are for services covered by the Medicare OPPS and those paid on separate fee schedules (e.g., ambulance services or durable medical equipment) or those paid on a cost basis (e.g., organ acquisition or flu vaccines). They do not include payments for clinical laboratory services. * Estimate Source: CMS, Office of the Actuary.

According to a recent Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MedPAC) report, spending increases are the result of both an increase in the volume of outpatient services and the mix of services4 (MedPAC, 2007c). Outpatient service volume grew rapidly from 2001, the first full year of prospective payment in the outpatient hospital setting, to 2005; however, the rate of increase slowed from 11.9 percent in 2002 to 3 percent in 2005 (Figure 1.2) (MedPAC, 2007c). Most of the growth in volume during this period was the result of an increase in the number of services per beneficiary. In addition to increases in the use of services per beneficiary, the complexity of services increased, further contributing to the escalation in costs.

Figure 1.2. Annual Growth in the Number of Medicare Outpatient Services (MedPAC 2007)

Note: Data are for hospitals covered under the Medicare OPPS. Source: (MedPAC, 2007),

hospital outpatient claims from CMS. These MedPAC analyses exclude separately paid drugs and pass-through devices.

A wide variety of care is provided in the hospital outpatient setting under OPPS, including evaluation and management (E&M) visits, services/procedures (such as diagnostic imaging and other tests), and the provision of drugs/biologicals. While procedures constituted only 18 percent of the volume of care, they represented 47 percent of the payments in 2005 (MedPAC, 2007b) (Table 1.1). Imaging constituted the second largest category based on volume (19 percent) and spending (23 percent) in 2005.

| Volume | % of total | Payments | % of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Service | Type of Service | ||

| Separately paid drugs/blood products | 29 | Procedures | 47 |

| Imaging | 19 | Imaging | 23 |

| Procedures | 18 | Evaluation and management | 14 |

| Evaluation and management | 16 | Separately paid drugs/blood products | 11 |

| Tests | 13 | Tests | 4 |

| Pass-through drugs | 4 | Pass-through drugs | 1 |

| Source: (MedPAC 2007b) | |||

The growth in the volume of and spending for hospital outpatient services highlights the importance of this care setting for Medicare beneficiaries. At present, there is no understanding of the quality of care delivered in this setting, and accountability for performance is only beginning to emerge through modifications to the Reporting Hospital Quality Data for Annual Payment Update Program (RHQDAPU Program). Given the likelihood for substantial deficits in care — both the under use and over use of services in this setting — important opportunities for quality improvement and potential cost reduction exist. The current absence of performance measurement and transparency in this setting hinders the ability to understand where deficits are occurring and how to adjust payment policies to drive improvements in care.

Federal Actions to Reform the System

On August 22, 2006, President Bush issued an Executive Order, “Promoting Quality and Efficient Health Care,” that requires the federal government to: (1) ensure that federal health care programs promote quality and efficient delivery of health care and (2) make readily useable information available to beneficiaries, enrollees, and providers (Bush, 2006). To support this mandate, DHHS Secretary Michael Leavitt embraced “four cornerstones” for building a value-driven health care system:

- Connecting the health system through the use of health information technology (HIT)

- Measuring and making transparent quality information

- Measuring and making transparent price information

- Using incentives to promote high-quality and cost-effective care (Leavitt, 2006).

Building on these four cornerstones, CMS has taken steps toward measuring and making quality information transparent to become a value-based purchaser of care. A key example is the CMS Reporting Hospital Quality Data for Annual Payment Update (RHQDAPU) Program, initially enacted under the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA)5, and expanded through the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 20056. The RHQDAPU Program provides differential payment updates in the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) to hospitals based on whether they publicly report their performance on a defined set of inpatient care performance measures. As part of Section 109 of the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (TRHCA)7, Congress established new requirements such that hospitals are required to report hospital outpatient quality data in order to secure the full annual payment update under the OPPS. The new program is referred to as the Hospital Outpatient Quality Data Reporting Program (HOP QDRP).

According to the Proposed OPPS Rule, effective January 2008, hospitals will be required to submit performance data on a set of 10 measures of care provided in the hospital outpatient setting (Table 1.2) to secure their full payment update in Calendar Year (CY) 2009 and each subsequent year;8 the Medicare annual OPPS fee schedule increase amount will be reduced by 2.0 percentage points for any "subsection (d) hospital" that does not submit required outpatient department quality data (CMS, 2007).9

| Measure | Source |

|---|---|

| Emergency Department Transfer: Aspirin at Arrival for AMI (acute myocardial infarction) | Oklahoma Foundation for Medical Quality (OFMQ) |

| Emergency Department Transfer: Median Time to Fibrinolysis for AMI | OFMQ |

| Emergency Department Transfer: Fibrinolytic Therapy Received Within 30 Minutes of Arrival | OFMQ |

| Emergency Department Transfer: Median Time to Electrocardiogram | OFMQ |

| Emergency Department Transfer: Median Time to Transfer for Primary PCI | OFMQ |

| Heart Failure: ACE or ARB Therapy for LVSD | American Medical Association Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (AMA/PCPI) |

| Perioperative Care: Timing of Antibiotic Prophylaxis | AMA/PCPI |

| Perioperative Care: Selection of Prophylactic Antibiotic | AMA/PCPI |

| Empiric Antibiotic for Community Acquired Pneumonia | AMA/PCPI |

| Hemoglobin A1c Poor Control in Type 1 or 2 Diabetes Mellitus | National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) |

Of the 10 measures, the five emergency department transfer measures were developed by the Oklahoma Foundation for Medical Quality (OFMQ), while the five other measures are physician-level measures for which existing measurement specifications have been revised by the OFMQ to address care provided in hospital outpatient settings. Anticipating the need for a broader range of measures to support this legislative mandate, CMS is seeking public comment on 30 additional measures of care provided in the hospital outpatient setting that are under consideration for reporting in future years (CMS, 2007) (see Appendix A).

Purpose of This Study

In September 2006, the DHHS Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), in collaboration with CMS, issued a contract to the RAND Corporation to conduct a review of performance measures that might be applicable to care provided in the hospital outpatient setting. Specifically, RAND was tasked to conduct an environmental scan to:

- Determine the leading conditions treated and services/procedures provided in the outpatient setting as a function of volume and costs,

- Identify existing performance measures that may be applicable to care provided in this setting; and

- Identify measurement gaps.

The remainder of this report presents the findings of RAND’s environmental scan and is organized as follows:

- The framework and methods used in this study (Chapter 2);

- The results of an analysis of 2005 Medicare hospital outpatient data to determine key reasons for visits, as well as key services/procedures and drugs/biologicals provided in this setting, and of a scan of existing measures for those potentially relevant to hospital outpatient care (Chapter 3);

- A mapping of existing measures to the key reasons for visits, services/procedures, and drugs/biologicals relevant to the Medicare population, and discussion of gaps in existing measures (Chapter 4); and

- A summary of the key findings, including issues that need to be considered when developing measures for application in the hospital outpatient setting and a series of next steps for advancing CMS’ measures development work in the hospital outpatient setting (Chapter 5).

II. Analytic Framework and Methods

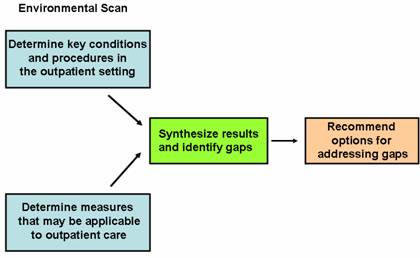

In this section, we present the approach we used to conduct this study. Figure 2.1 shows the organizing framework for our work. The environmental scan involved two main steps: (1) identification of the leading conditions treated and services/procedures provided in the outpatient setting (on the basis of cost and volume), and (2) identification of existing measures that may be applicable to outpatient care. In carrying out these steps, we conducted:

- An analysis of 2005 Medicare hospital outpatient data to determine conditions, services/procedures, and drugs/biologicals addressed in this setting,

- A scan for existing, publicly available measures potentially applicable to the hospital outpatient setting, and

- A series of semi-structured telephone discussions with representatives of medical specialty societies and hospital associations, informed by the analyses described in #1 and #2 above.

The methods for each of the data collection activities are described below. Having completed these data collection activities, we then synthesized the results to provide an initial assessment of which existing measures may reasonably apply to care provided in the hospital outpatient setting, and to identify gaps in those measures. This synthesis was used to inform our recommendations regarding next steps for advancing CMS’ measures development work in the hospital outpatient setting.

Due to the limited resources for this project, the work completed here should be viewed as a preliminary assessment which requires follow-on work to fully flesh out how to apply existing performance measures in this setting and where the most important measurement gaps are for guiding the use of resources in the future.

Figure 2.1. Framework Used in this Study

An environmental scan that takes the determing key conditions and procedures in the oupatient setting, and the determining measures that may be applicable to outpatient care; synthesizes the results, and identifies gaps; and recommends options for addressing the gaps.

Defining the Hospital Outpatient Setting

The hospital outpatient setting can be an elusive concept to define and the care provided in this setting is not homogenous across hospitals. While hospitals typically consider the Emergency Department (ED) to be part of the hospital outpatient setting, there is no standard classification of other care and services/procedures as “hospital outpatient.” The classification of a service as HOPS reflects the structure and organization of the local health system as well as the location where the service is provided, as opposed to the nature of the service itself. For example, facility charges for a hospital-based physician performing a colonoscopy in a hospital-based outpatient clinic would be billed under the OPPS. Meanwhile, another physician practicing in the same market, but not in the hospital-based outpatient department, and who is performing the same service/procedure may bill for practice expenses using the rates established as part of the Physician Fee Schedule.

For the purposes of our environmental scan, we defined the hospital outpatient setting as visits and/or services/procedures paid for under the Medicare OPPS. This care was further categorized for analyses and discussion in this report as either rendered in: (1) the ED, or (2) any other hospital-affiliated outpatient setting that is paid under OPPS (hereafter referred to as HOPS). We first classified services/procedures that obviously occur in the ED to the ED; all other services/procedures paid under the OPPS were classified as HOPS.

Methods

Analysis of Medicare Hospital Outpatient Data

RAND analyzed 2005 Medicare facility data for services paid through the hospital OPPS. The data file contained summary data aggregated to the diagnosis-service category level. This level of detail provides sufficient information to understand, in the aggregate, the types of services Medicare beneficiaries receive, but lacks specificity to describe individual patient encounters or episodes of care. CMS provided two data files, which included the diagnosis for an encounter,10 as well as visits aggregated to the Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC)11 level or the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) level. Each file contained code descriptions (APC, HCPCS, International Classification of Disease Version 9 or “ICD-9”), the total frequency, the APC paid in 2005, the 2007 payment rate for either the APC or HCPCS (total, and by diagnosis), and a CMS status indicator describing the type of service.

These data were analyzed to determine the following:

- The most common reasons (diagnoses) for visits (E&M services),

- The most frequent services/procedures provided,

- The services/procedures representing the largest costs within this setting,12 and

- The most frequent drugs and biologicals provided in this setting.

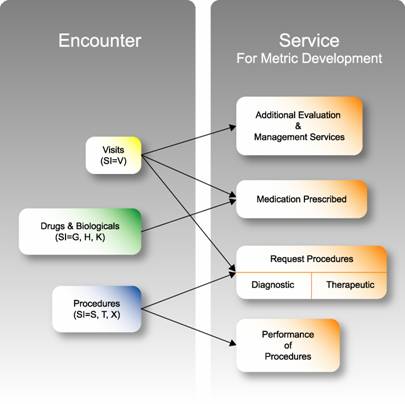

E&M visits were identified using the status indicator V (i.e., the status indicator associated with APC codes that indicate clinic or emergency department visits). Services/ procedures were identified with the status indicators S, T or X (i.e., the status indicators associated with APC codes that indicate significant services/procedures and ancillary services). Drugs and biologicals were identified using status indicators G (pass through drugs and biologicals), H (pass through devices, radiopharmaceuticals, brachytherapy), or K (non-pass through drugs and biologicals)13. The analyses did not include laboratory services14 or durable medical equipment (DME),15 which are not paid under OPPS.16

The total cost associated with the provision of each service/procedure was calculated by multiplying the frequency of the service/procedure by the 2007 APC payment for that service/procedure to obtain total Medicare costs. In our analyses, we applied 2007 payment rates to the 2005 utilization data; therefore, the estimates of 2007 spending based on these calculations assume that the volume and distribution of visits and services/procedures did not substantially change over the two year period.

Under Medicare OPPS rules, multiple APCs may be reported on a single claim when patients receive multiple, separately billable services. For example, a patient visiting the HOPS may be billed for a clinic visit (an E&M-related service), a chest x-ray, and an electrocardiogram during the same encounter. Because the files we used for these analyses did not have patient- or encounter-specific data, we were unable to explicitly link visit data (i.e., APCs with status indicator V) with significant services/procedures (i.e., APCs with status indicator S, T or X). Therefore, we cannot describe the spectrum of individual services a Medicare beneficiary receives during a single visit (e.g., we could not identify at the patient level, multiple services/procedures as part of the same encounter, or patients with E&M services/procedures during the same encounter).

For each common or costly APC representing services/procedures, clinical experts at RAND identified the specialties that most frequently bill for these professional services based on data from the American Medical Association’s (AMA) 2005 Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) database. This database indicates the specialties that commonly bill for individual services/procedures at the HCPCS (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT]) level. In making the determination, RAND examined the providing specialties for any HCPCS code that accounted for at least five percent of the claims within an individual APC in 2005. This assignment was done to assist in the identification of measures potentially relevant to common services delivered in the hospital outpatient setting.

To facilitate examination of diagnoses associated with visits and services/procedures, RAND researchers grouped common diagnoses. Individual diagnoses were aggregated into diagnostic groups by two physicians using headers in the ICD-9-CM codebook as a guide.17 Diagnoses were also grouped by organ or body systems. The main driver for grouping diagnoses was to ensure that the most common diagnoses that have multiple diagnosis codes at the four-digit level (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) were aggregated, thereby allowing our analyses to accurately reflect their collective frequency and costs.18

We examined E&M visits separately from services/procedures to assist us in our efforts to identify performance measures, as E&M visits mimic the type of preventive, acute and chronic care provided in the ambulatory setting for which a large number of measures currently exist. Additionally, all data analyses were performed separately for the ED and the HOPS, given the distinct types of care provided by these two departments.

Scan of Existing Measures

The second component of the environmental scan was a search for existing performance measures. Between January and June 2007, RAND searched for existing, publicly available measures of any type (e.g., process, outcome) that might be appropriate to assess care provided in the hospital outpatient setting. We reviewed the websites of organizations known to produce, list, and/or approve outpatient/ambulatory care measures, including the following organizations:

- NCQA,

- AQA Alliance (formerly known as the Ambulatory Quality Alliance),

- CMS,

- American Medical Association Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (AMA/PCPI),

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) National Measures Clearinghouse,

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI),

- RAND,

- National Quality Forum (NQF), and

- Websites of medical specialty societies.

Finally, Google searches were performed using the following terms: hospital outpatient performance, hospital outpatient performance measures, health care quality measures, health care performance measurement, and physician performance measurement. Measures identified in the search were categorized by their application to particular diseases and/or conditions.

Discussions with Medical Specialty Societies and Hospital Associations

Between April and June 2007, RAND held telephone discussions with nine medical specialty societies and four hospital associations to determine whether these organizations had existing measures, measures in the pipeline, or knew about measures being developed by other organizations that could be used to assess performance in the hospital outpatient setting as well as potential challenges associated with performance measurement in this setting. To focus the conversation with medical specialty societies, RAND provided each discussant with background information on the most frequent conditions and services that members of the given specialty provide to Medicare patients in the outpatient setting. RAND also provided discussants with background information on measures identified through its web searches that might be applicable to the care delivered by the given specialty in the hospital outpatient setting. Appendix B contains the list of the organizations with which RAND held discussions.

Synthesis of Findings from Environmental Scan

We mapped the clinical measures identified through our measures scan to the most common diagnoses and conditions treated, services/procedures, and drugs/biologicals provided in the HOPS, as identified in the data analysis described above. In the mappings of measures to diagnoses and conditions, we used subcategories of the diagnostic groupings to better match reasons for visits to topics relevant to metric development. For example, within endocrinology, we separately identified the common diagnoses of diabetes and thyroid disease – clinical conditions with sufficient specificity that measures could be matched to these diagnoses.

In conducting our work, we note several limitations which CMS could consider addressing in subsequent work to develop performance measures in the outpatient hospital setting:

- We elected to focus on the HOPS (as opposed to the ED) for this measures mapping exercise because the majority of existing measures correspond to conditions and diagnoses that most commonly occur in the HOPS, rather than the ED. We acknowledge that some conditions and services/procedures occur more frequently in the ED setting; therefore a separate synthesis focusing on mapping measures to the care provided in the ED merits consideration for future analyses.

- The mapping of measures to common diagnoses and clinical conditions focused on encounters that involved only E&M care for acute and chronic conditions.

We recognize that other encounters are specifically for a service/procedure (e.g., mammography), and many encounters involve both E&M care and services/procedure(s). Given that multiple APCs are frequently submitted for an encounter, future analyses examining data at the patient encounter level would provide a better understanding of services provided at that level.

We then combined the results from the mapping exercise described above with the findings from our discussions to identify measurement gaps. Gaps refer to clinical areas or other domains of care where care was delivered but few or no measures exist or areas flagged by discussants as having a lack of existing measures. The gap analysis was organized by the six IOM aims viewed as important in the provision of high-quality care (IOM, 2001). This gap analysis considered both the HOPS and the ED.

III. Findings from the Environmental Scan

In the discussion that follows, we summarize the results from our analysis of 2005 Medicare facility data for services paid through the hospital OPPS. The analyses were conducted to determine the most common reasons for visits in this setting, the most frequent and the most costly services/procedures rendered, as well as the drugs and biologicals that represented the largest share of costs in this setting. This analysis is a first step in determining which conditions and services/procedures might be suitable for measurement, given that they represent high volume or high costs to the Medicare program. We then present the results of our scan of existing measures, identifying those that could potentially be applied to the care delivered in the hospital outpatient setting. The discussion draws upon findings from our discussions with medical specialty societies and hospital associations.

Findings from Analysis of Medicare Data

Overall Finding

As noted previously, we examined E&M visits separately from services/procedures to assist us in identifying measures that are relevant to each category, given that different types of measures apply. Additionally, all data analyses were performed separately for the ED and the HOPS, given the distinct type of care provided in these two settings.

Based on our analysis of the 2005 Medicare OPPS facility data, CMS was billed for 15,325,267 E&M encounters and 78,538,882 services/procedures in the HOPS. In the same year CMS was billed for 11,426,386 E&M encounters and 22,494,724 services/procedures in the ED. Thus, in 2005, services/procedures represented a significant volume of the care provided in the hospital outpatient setting. More specifically, the top 20 most frequent services/procedures accounted for 58 percent of total services/procedures in the HOPS, and 94 percent of total services/procedures in the ED.

In terms of cost, had 2007 payment rates been applied in 2005, CMS would have paid $19.1 billion for services/procedures in the HOPS, and $1.7 billion for services/procedures in the ED.19 The top 20 services/procedures as a fraction of total costs would have accounted for 44 percent of total dollars in the HOPS, and 83 percent of total dollars in the ED. In both the HOPS and ED, a relatively small share of the services/procedures represented a significant proportion of costs — especially in the ED.

| Hospital Outpatient Setting | Emergency Department | |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation and Management (E&M) Visits21 | ||

| Total E&M Visits | 15,325,267 | 11,426,386 |

| Total Cost of E&M Visits | $1,000,166,031 | $1,774,375,562 |

| Services/Procedures | ||

| Total Services/Procedures | 78,538,882 | 22,494,724 |

| Top 20 Services/Procedures by Volume | 45,806,040 | 21,227,715 |

| Top 20 Percent of Total Volume | 58% | 94% |

| Total Service/Procedure Expenditures | $19,055,431,864 | $1,709,238,878 |

| Top 20 Services/Procedures by Expenditure | $8,420,413,916 | $1,424,886,799 |

| Top 20 Percent of Total Expenditure | 44% | 83% |

Common Reasons for Visits in the Hospital Outpatient Setting and Emergency Department

Figures 3.1 and 3.2 and Table 3.1 highlight the common reasons for E&M visits to the HOPS and ED. The clinical categories in Figures 3.1 and 3.2 represent 100 percent of the primary diagnoses associated with visits to the HOPS and ED, respectively, and are organized alphabetically. Table 3.1 provides additional information for the clinical categories that represent at least five percent of either HOPS or ED visits. Within these clinical categories, Table 3.1 presents more detailed diagnostic groups that account for at least 0.5 percent or more of the total diagnoses. The diagnostic groups are listed in order of the HOPS percentage of total diagnoses. Therefore, the sum of the percentages for diagnostic groups within a clinical category will not equal the percentage for the category. Appendix C presents more detailed information (i.e., for all of the clinical categories).

Figure 3.1. HOPS Visits by Clinical Category, 2005

Figure 3.2. ED Visits by Clinical Category, 2005

The analysis reveals that in 2005 the key reasons for HOPS (i.e., non-ED) hospital outpatient visits tended to be similar to the major reasons for visits in the physician office setting (see Figure 3.1 and Table 3.1). General medical conditions (35.2 percent) constitute the largest proportion of HOPS visits by Medicare patients and address common chronic conditions, such as hypertension (7.4 percent), aftercare for procedures (6.4 percent), and specific and general symptoms (e.g., fever, dizziness) for which an underlying etiology is sought (4.6 percent). Oncology and neoplasia conditions were the next most frequent reasons for visits (13.1 percent), followed by orthopedic conditions (10.4 percent), particularly diagnoses such as back pain and arthritis. Endocrinology conditions, such as diabetes, were the fourth most common clinical category, representing 7.0 percent of HOPS visits. These findings are similar to those of the 2004 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey in which the top diagnoses in physician offices for individuals ages 65 and older were: (1) malignant neoplasm, (2) essential hypertension, (3) diabetes mellitus, (4) arthroplasties and related disorders, and (5) heart disease, excluding ischemic (Hing et al, 2006).

Our analysis also reveals that in 2005 general medical conditions (43.4 percent) were the key reasons for ED visits (see Figure 3.2 and Table 3.1). The most common reason for such visits was found to be “symptoms” (20.4 percent), generally for unanticipated acute care where patients either present with: (1) new onset of symptoms, from which a differential diagnosis is created and a plan developed to determine the etiology of the presenting findings; or (2) a new or worsening diagnosis for which acute intervention is sought. Injury, either orthopedic (e.g., back pain, sprains, fractures) or of a more general nature (e.g., laceration), constituted the next most common reason for ED encounters within the general medical category (6.15 percent). Given the nature of ED practice, patients’ reasons for seeking emergency care overlap nearly every clinical discipline.

|

HOPS

|

ED

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Encounters |

15,325,267*

|

11,426,386*

|

||||

| Clinical Category |

Diagnostic Group

|

Diagnostic Group

|

||||

| Medicine-General | 35.21% | 43.40% | ||||

| Hypertension | 7.42% | Symptoms | 20.35% | |||

| Aftercare, specific procedures | 6.40% | Injury | 6.15% | |||

| Symptoms | 4.48% | COPD and related | 3.49% | |||

| Metabolic/nutrition | 2.37% | Acute respiratory infection | 2.78% | |||

| Health system encounter | 2.18% | Metabolic/nutrition | 1.47% | |||

| COPD and related | 1.99% | Complications | 1.41% | |||

| Venous disease | 1.97% | Hypertension | 1.39% | |||

| General exam | 1.49% | Infectious and parasitic disease | 1.23% | |||

| Acute respiratory infection | 1.34% | Aftercare, specific procedures | 1.08% | |||

| Complications | 1.04% | Venous disease | 0.72% | |||

| Arterial disease | 0.83% | Poisonings | 0.55% | |||

| Upper respiratory tract | 0.56% | Toxic effects-external causes | 0.50% | |||

| Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia | 13.10% | 0.88% | ||||

| Cancer | 9.17% | Hematology | 0.58% | |||

| Hematology | 2.35% | |||||

| Neoplasm-uncertain behavior | 0.54% | |||||

| Orthopedics | 10.39% | 16.61% | ||||

| Back disorders | 3.92% | Back disorders | 3.94% | |||

| Arthropathies | 1.95% | Sprains and strains | 3.63% | |||

| Rheumatism | 1.73% | Fracture | 2.75% | |||

| Other joint disorders | 1.31% | Rheumatism | 2.59% | |||

| Osteopathies, chondropathies | 0.90% | Other joint disorders | 2.02% | |||

| Arthropathies | 0.70% | |||||

| *Totals represent all encounters associated with an E&M claim in 2005 | ||||||

|

HOPS

|

ED

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Encounters |

15,325,267*

|

11,426,386*

|

||||

| Clinical Category |

Diagnostic Group

|

Diagnostic Group

|

||||

| Medicine-Endocrinology | 7.03% | 1.62% | ||||

| Endocrine, metabolic | 6.98% | Endocrine, metabolic | 1.62% | |||

| Medicine-Cardiology | 6.68% | 3.45% | ||||

| Conduction/dysrhythmias | 2.48% | Conduction/dysrhythmias | 1.28% | |||

| Ischemic heart | 1.82% | Heart failure | 0.86% | |||

| Heart failure | 1.33% | Symptoms | 0.62% | |||

| Ischemic heart | 0.60% | |||||

| Dermatology | 6.65% | 4.21% | ||||

| Other skin diseases | 4.39% | Skin infections | 1.93% | |||

| Skin infections | 0.81% | Symptoms | 1.09% | |||

| Inflammatory skin conditions | 0.75% | Other skin diseases | 0.63% | |||

| Symptoms | 0.60% | Inflammatory skin conditions | 0.56% | |||

| Medicine-GI | 2.37% | 6.26% | ||||

| Upper GI | 0.62% | Symptoms | 1.78% | |||

| Upper GI | 1.17% | |||||

| Functional digestive | 0.93% | |||||

| Inflammatory bowel | 0.84% | |||||

| Urology | 2.12% | 5.32% | ||||

| Symptoms | 0.61% | Urinary tract infection | 2.40% | |||

| Urinary tract infection | 0.53% | Symptoms | 1.20% | |||

| Notes: *Totals represent all encounters associated with an E&M claim in 2005. Table note: The percentages associated with each diagnosis within a clinical category may not sum to the percentage for the clinical category given that we only list diagnoses at 0.5 percent or higher. |

||||||

Most Commonly Provided Services/Procedures and Associated Diagnoses in the Hospital Outpatient Setting and Emergency Department

Tables 3.2 and 3.3 highlight the 20 most common classes of services/procedures, grouped by APC, and their associated diagnoses in the HOPS and ED setting, respectively, based upon the analysis of 2005 Medicare data. For each of the APCs presented in the table, the five most common primary diagnosis groups associated with the APC are presented. In some cases, findings cluster into fewer than five key diagnostic categories, so fewer than five are listed. Additionally, Tables 3.2 and 3.3 present the physician specialty most likely to provide the given service/procedure, as distinguished from the ordering specialty (i.e., the physician requesting the service/procedure, but not actually providing it).

The most frequent services/procedures in the HOPS were ancillary services/procedures commonly used to diagnose and treat many different clinical symptoms and conditions. These include radiology services (e.g., x-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, ultrasound), surgical pathology (i.e., Level III pathology, commonly used by pathologists and dermatologists), electrocardiograms, and drug administration. Most primary services/procedures (e.g., cataract extraction, angiography, arthroscopic surgery), while frequent, do not rise to the top of the OPPS services/procedures because they are dwarfed by the volume of ancillary services. The most common HOPS service/procedure (X-ray) accounted for 12 percent of the total services/procedures examined; and every other service/procedure listed in the top 20 for the HOPS accounted for five percent or less, each, of the total.

As in the HOPS, the most frequent services/procedures in the ED were ancillary services/procedures, especially radiology services. In the ED, the top few services/procedures account for a larger proportion than in the HOPS and the proportion represented by other services/procedures diminishes quickly thereafter. For example, the top two most common services/procedures in the ED -- X-rays and electrocardiograms-- accounted for approximately 30 percent and 16 percent, respectively, of the services/procedures included in these analyses; the remaining top 20 each accounted for nine percent or less of the total of services/procedures included in these analyses.

The total number of any one or a group of related services/procedures may have important implications when considering performance measures. While the overall volume of services/procedures is high — for example, in the 2005 Medicare data, there were over 78 million services/procedures performed in the HOPS and 22 million in the ED — as data are parsed at the hospital level to examine specific conditions or services/procedures, the sample size may be too small at the level of an individual hospital to be able to produce stable estimates of performance.

| Rank | Frequency | Percent of Total | APC | APC Description | Most Common Clinical Categories Within APC | Specialty Providing Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9,526,216 | 12.13% | 260 | Level I Plain Film Except Teeth | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-Cardiology, Urology | Radiology, Facility |

| 2 | 3,934,292 | 5.01% | 343 | Level III Pathology | Medicine-GI, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-General, Dermatology, Surgery-General | Pathology, Dermatology |

| 3 | 3,049,223 | 3.88% | 99 | Electrocardiograms | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology, Orthopedics, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Surgery-General | Internal Medicine, Cardiology |

| 4 | 2,984,113 | 3.80% | 301 | Level II Radiation Therapy | Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-General | Radiation Oncology |

| 5 | 2,873,862 | 3.66% | 283 | Computerized Axial Tomography with Contrast Material | Medicine-General, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-GI, Orthopedics, Urology | Radiology, Facility |

| 6 | 2,797,689 | 3.56% | 437 | Level II Drug Administration | Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology, Orthopedics, Medicine-Infectious Disease | Facility |

| 7 | 2,303,689 | 2.93% | 95 | Cardiac Rehabilitation | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology | Cardiology |

| 8 | 2,091,415 | 2.66% | 266 | Level II Diagnostic and Screening Ultrasound | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Urology, Gynecology, Medicine-GI | Urology, Radiology |

| 9 | 1,831,696 | 2.33% | 409 | Red Blood Cell Tests | Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Medicine-Cardiology, Medicine-GI | Laboratory |

| Rank | Frequency | Percent of Total | APC | APC Description | Most Common Clinical Categories Within APC | Specialty Providing Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1,765,455 | 2.25% | 440 | Level V Drug Administration | Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology, Orthopedics, Dermatology | Facility |

| 11 | 1,622,281 | 2.07% | 697 | Level I Echocardiogram Except Transesophageal | Medicine-Cardiology, Medicine-General, | Cardiology, Internal Medicine |

| 12 | 1,467,273 | 1.87% | 143 | Lower GI Endoscopy | Medicine-GI, Medicine-General, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia | Gastroenterology, General Surgery, Internal Medicine |

| 13 | 1,377,463 | 1.75% | 433 | Level II Pathology | Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-GI, Medicine-General, Urology, Surgery-General | Pathology |

| Laboratory | ||||||

| 14 | 1,351,504 | 1.72% | 304 | Level I Therapeutic Radiation Treatment Preparation | Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-General | Radiation Oncology |

| 15 | 1,217,589 | 1.55% | 368 | Level II Pulmonary Tests | Medicine-General | Family Practice, Internal Medicine |

| 16 | 1,200,061 | 1.53% | 438 | Level III Drug Administration | Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology, Orthopedics, Medicine-GI | Facility |

| 17 | 1,175,648 | 1.50% | 325 | Group Psychotherapy | Psychiatry | Psychiatry |

| 18 | 1,160,024 | 1.48% | 332 | Computerized Axial Tomography and Computerized Angiography without Contrast | Medicine-General, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Orthopedics, Urology, Neurology | Radiology, Facility |

| 19 | 1,058,882 | 1.35% | 267 | Level III Diagnostic and Screening Ultrasound | Medicine-General, Neurology, Medicine-Cardiology, Orthopedics, Dermatology | Cardiology, Vascular Surgery |

| 20 | 1,017,665 | 1.30% | 399 | Nuclear Medicine Add-on Imaging | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology | Radiology, Cardiology |

| Rank | Frequency | Percent of Total | APC | APC Description | Most Common Clinical Categories Within APC | Specialty Providing Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6,638,015 | 29.51% | 0260 | Level I Plain Film Except Teeth | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Medicine-Cardiology, Medicine-GI, Surgery-General | Radiology, Facility |

| 2 | 3,595,431 | 15.98% | 0099 | Electrocardiograms | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology, Medicine-GI, Orthopedics, Neurology | Internal Medicine, Cardiology |

| 3 | 1,984,224 | 8.82% | 0437 | Level II Drug Administration | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Surgery-General, Head and Neck, Medicine-GI | Facility |

| 4 | 1,913,623 | 8.51% | 0438 | Level III Drug Administration | Medicine-General, Medicine-GI, Orthopedics, Medicine-Cardiology, Urology | Facility |

| 5 | 1,834,962 | 8.16% | 0332 | Computerized Axial Tomography and Computerized Angiography without Contrast | Medicine-General, Head and Neck, Urology, Orthopedics, Neurology | Radiology, Facility |

| 6 | 1,223,868 | 5.44% | 0440 | Level V Drug Administration | Medicine-General, Medicine-GI, Urology, Orthopedics, Medicine-Cardiology | Facility |

| 7 | 756,543 | 3.36% | 0077 | Level I Pulmonary Treatment | Medicine-General | Family Practice, Internal Medicine |

| 8 | 587,764 | 2.61% | 0261 | Level II Plain Film Except Teeth Including Bone Density Measurement | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Medicine-GI, Urology, Head and Neck | Radiology, Facility |

| 9 | 507,923 | 2.26% | 0283 | Computerized Axial Tomography with Contrast Material | Medicine-General, Medicine-GI, Orthopedics, Urology, Surgery-General | Radiology, Facility |

| 10 | 382,798 | 1.70% | 0024 | Level I Skin Repair | Head and Neck, Surgery-General, Medicine-General, Orthopedics | Dermatology |

| Rank | Frequency | Percent of Total | APC | APC Description | Most Common Clinical Categories Within APC | Specialty Providing Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 306,538 | 1.36% | 266 | Level II Diagnostic and Screening Ultrasound | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Dermatology, Medicine-GI, Urology | Urology, Radiology, Surgery |

| 12 | 274,110 | 1.22% | 409 | Red Blood Cell Tests | Medicine-General, Medicine-GI, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Orthopedics, Urology | Laboratory |

| 13 | 270,657 | 1.20% | 58 | Level I Strapping and Cast Application | Orthopedics | Emergency Medicine, Podiatry |

| 14 | 248,571 | 1.11% | 340 | Minor Ancillary Procedures | Urology, Medicine-General, Medicine-GI, Orthopedics, Head and Neck | Urology, Ophthalmology |

| 15 | 154,572 | 0.69% | 697 | Level I Echocardiogram Except Transesophageal | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology, Neurology | Cardiology |

| 16 | 143,991 | 0.64% | 282 | Miscellaneous Computerized Axial Tomography | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Head and Neck | Radiology, Facility |

| 17 | 124,793 | 0.55% | 345 | Level I Transfusion Laboratory Procedures | Medicine-General, Medicine-GI, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia | Laboratory |

| 18 | 111,433 | 0.50% | 267 | Level III Diagnostic and Screening Ultrasound | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Neurology, Dermatology, Medicine-Cardiology | Cardiology, Vascular Surgery, Radiology |

| 19 | 87,602 | 0.39% | 269 | Level II Echocardiogram Except Transesophageal | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology, Neurology, Orthopedics, Medicine-GI | Cardiology |

| 20 | 80,297 | 0.36% | 399 | Nuclear Medicine Add-on Imaging | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology | Radiology, Cardiology |

Services/Procedures and Associated Diagnoses Representing the Largest Share of Costs in the Hospital Outpatient Setting and Emergency Department

Tables 3.4 and 3.5 highlight the 20 costliest services/procedures in the HOPS and ED, respectively, as well as the associated diagnoses based upon analysis of 2005 Medicare data with 2007 APC payment rates applied.25 These data show that, had 2007 payment rates been in force in 2005, many of the most common services/procedures also would have accounted for a substantial share of total costs, although there are some changes in distribution given the relative weight of the more costly services. For example, while Level I plain films (APC 0260) and Level III Pathology (APC 0343) are the first and second most frequent APCs billed in the HOPS, APC 0260 ranks only sixth in cost and APC 0343 is not among the top 20 most costly services/procedures. Similarly, neither cataract surgery (APC 0246) nor cardiac catheterization (APC 0080), the two services/procedures accounting for the greatest share of payments for HOPS services, are among the 20 most frequent services/procedures provided in the HOPS. In the ED, CT scans were found to be the costliest (vs. X-rays which were most frequent). No single service/procedure accounted for a large proportion of the total cost; however, given the magnitude of the costs involved, even one to two percent of total costs remains significant.

| Rank | Total Cost | Percent of Total | APC | APC Description | Most Common Clinical Categories Within APC | Specialty Providing Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $998,098,614 | 5.24% | 246 | Cataract Procedures with IOL Insert | Ophthalmology | Ophthalmology |

| 2 | $893,140,496 | 4.69% | 80 | Diagnostic Cardiac Catheterization | Medicine-Cardiology, Medicine-General | Cardiology |

| 3 | $790,845,474 | 4.15% | 143 | Lower GI Endoscopy | Medicine-GI, Medicine-General, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Surgery-General | Gastroenterology, General Surgery, Internal Medicine |

| 4 | $721,166,930 | 3.78% | 283 | Computerized Axial Tomography with Contrast Material | Medicine-General, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-GI, Orthopedics, Urology | Radiology, Facility |

| 5 | $460,378,894 | 2.42% | 141 | Level I Upper GI Procedures | Medicine-GI, Medicine-General, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Surgery-General | Gastroenterology |

| 6 | $415,343,018 | 2.18% | 260 | Level I Plain Film Except Teeth | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-Cardiology, Urology | Radiology, Facility |

| 7 | $408,942,846 | 2.15% | 301 | Level II Radiation Therapy | Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-General | Radiation Oncology |

| 8 | $371,722,046 | 1.95% | 280 | Level III Angiography and Venography | Medicine-General, Neurology, Medicine-Cardiology | Cardiology, Facility |

| 9 | $347,637,485 | 1.82% | 107 | Insertion of Cardioverter-Defibrillator | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology | Cardiology |

| 10 | $345,378,970 | 1.81% | 336 | Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetic Resonance Angiography without Contrast | Orthopedics, Medicine-General, Neurology, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Neurology/Neurosurgery | Radiology, Facility |

| Rank | Total Cost | Percent of Total | APC | APC Description | Most Common Clinical Categories Within APC | Specialty Providing Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | $305,728,764 | 1.60% | 207 | Level III Nerve Injections | Orthopedics | Anesthesia, Pain Management |

| 12 | $304,144,743 | 1.60% | 337 | MRI and Magnetic Resonance Angiography without Contrast Material followed | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Neurology, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Ophthalmology | Radiology, Facility |

| 13 | $283,460,736 | 1.49% | 131 | Level II Laparoscopy | Surgery-General | Surgery-General, OB/GYN |

| 14 | $282,675,723 | 1.48% | 81 | Non-Coronary Angioplasty or Atherectomy | Medicine-General, Medicine-Nephrology, Medicine-Cardiology | Radiology, Nephrology |

| 15 | $282,329,852 | 1.48% | 154 | Hernia/Hydrocele Procedures | Surgery-General | Surgery-General |

| 16 | $272,367,293 | 1.43% | 41 | Level I Arthroscopy | Orthopedics | Orthopedics, Hand Surgery |

| 17 | $256,608,392 | 1.35% | 412 | IMRT Treatment Delivery | Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Medicine-General | Radiation Oncology |

| 18 | $238,689,974 | 1.25% | 108 | Insertion/Replacement/Repair of Cardioverter-Defibrillator Leads | Medicine-Cardiology, Medicine-General | Cardiology |

| 19 | $221,360,707 | 1.16% | 377 | Level III Cardiac Imaging | Medicine-Cardiology, Medicine-General | Cardiology |

| 20 | $220,392,959 | 1.16% | 332 | Computerized Axial Tomography and Computerized Angiography without Contrast | Medicine-General, Medicine-Oncology/Neoplasia, Orthopedics, Urology, Neurology | Radiology, Facility |

| Rank | Total Payment | Percent of Total | APC | APC Description | Most Common Clinical Categories Within APC | Specialty Providing Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $348,624,430 | 20.40% | 332 | Computerized Axial Tomography and Computerized Angiography without Contrast | Medicine-General, Head and Neck, Urology, Orthopedics, Neurology | Radiology, Facility |

| 2 | $289,417,454 | 16.93% | 260 | Level I Plain Film Except Teeth | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Medicine-Cardiology, Medicine-GI, Surgery-General | Radiology, Facility |

| 3 | $136,094,122 | 7.96% | 440 | Level V Drug Administration | Medicine-General, Medicine-GI, Urology, Orthopedics, Medicine-Cardiology | Radiology, Facility |

| 4 | $127,458,198 | 7.46% | 283 | Computerized Axial Tomography with Contrast Material | Medicine-General, Medicine-GI, Orthopedics, Urology, Surgery-General | Radiology, Facility |

| 5 | $93,423,075 | 5.47% | 438 | Level III Drug Administration | Medicine-General, Medicine-GI, Orthopedics, Medicine-Cardiology, Urology | Facility |

| 6 | $83,737,588 | 4.90% | 99 | Electrocardiograms | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology, Medicine-GI, Orthopedics, Neurology | Internal Medicine, Cardiology |

| 7 | $48,117,432 | 2.82% | 437 | Level II Drug Administration | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Surgery-General, Head and Neck, Medicine-GI | Facility |

| 8 | $44,164,587 | 2.58% | 261 | Level II Plain Film Except Teeth Including Bone Density Measurement | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Surgery-General, Head and Neck, Medicine-GI | Radiology, Facility |

| 9 | $34,926,490 | 2.04% | 24 | Level I Skin Repair | Head and Neck, Surgery-General, Medicine-General | Dermatology |

| 10 | $31,091,509 | 1.82% | 80 | Diagnostic Cardiac Catheterization | Medicine-Cardiology, Medicine-General | Cardiology |

| Rank | Total Payment | Percent of Total | APC | APC Description | Most Common Clinical Categories Within APC | Specialty Providing Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | $29,406,190 | 1.72% | 266 | Level II Diagnostic and Screening Ultrasound | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Dermatology, Medicine-GI, Urology | Urology, Radiology |

| 12 | $19,823,305 | 1.16% | 333 | Computerized Axial Tomography and Computerized Angiography without Contrast | Medicine-General, Medicine-GI, Urology, Orthopedics, Surgery-General | Radiology, Facility |

| 13 | $19,371,442 | 1.13% | 662 | Computerized Tomography Angiography | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Medicine-Cardiology, Neurology, Medicine-GI | Radiology, Facility |

| 14 | $17,646,836 | 1.03% | 58 | Level I Strapping and Cast Application | Orthopedics, Medicine-General | Emergency Medicine, Podiatry |

| 15 | $17,331,919 | 1.01% | 377 | Level III Cardiac Imaging | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology | Cardiology |

| 16 | $17,313,659 | 1.01% | 269 | Level II Echocardiogram Except Transesophageal | Medicine-General, Medicine-Cardiology, Neurology, Orthopedics, Medicine-GI | Cardiology |

| 17 | $17,241,882 | 1.01% | 336 | Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetic Resonance Angiography without Contrast | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Neurology, Head and Neck, Dermatology | Radiology, Facility |

| 18 | $16,854,241 | 0.99% | 267 | Level III Diagnostic and Screening Ultrasound | Medicine-General, Orthopedics, Neurology, Dermatology, Medicine-Cardiology | Cardiology, Vascular Surgery |

| 19 | $16,440,588 | 0.96% | 141 | Level I Upper GI Procedures | Medicine-General, Medicine-GI | Gastroenterology |

| 20 | $16,401,852 | 0.96% | 77 | Level I Pulmonary Treatment | Medicine-General | Family Practice, Internal Medicine |

Most Frequent Used Drugs and Biologicals in the Hospital Outpatient Setting and Emergency Department

Table 3.6 shows the 50 most frequent, separately billed drugs and biologicals associated with services in the HOPS and ED.28 In both the HOPS and ED, imaging contrast material, blood products and medications associated with cancer chemotherapy are among the most frequently used. In the ED, several thrombolytic agents are also frequently used. These findings derive from the data provided by CMS and have not been aggregated by drug or drug class. Additional analyses of drugs and biologicals would inform opportunities for measure development.

|

HOPS

|

Emergency Department

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC | APC definition | Volume | APC | APC definition | Volume |

| 4646 | Contrast 300-399 MGs iodine | 951,639 | 768 | Ondansetron hcl injection | 180,380 |

| 733 | Non esrd epoetin alpha inj | 610,121 | 4646 | Contrast 300-399 MGs iodine | 124,136 |

| 768 | Ondansetron hcl injection | 486,806 | 750 | Dolasetron mesylate | 27,611 |

| 1600 | Tc99m sestamibi | 359,301 | 1600 | Tc99m sestamibi | 26,186 |

| 954 | RBC leukocytes reduced | 309,368 | 954 | RBC leukocytes reduced | 21,140 |

| 734 | Darbepoetin alfa, non esrd | 303,060 | 705 | Tc99m tetrofosmin | 17,722 |

| 9027 | Supp- paramagnetic contr mat | 209,894 | 9223 | Inj adenosine, tx dx | 17,236 |

| 705 | Tc99m tetrofosmin | 203,824 | 7028 | Fosphenytoin, 50 mg | 10,410 |

| 1775 | FDG, per dose (4-40 mCi/ml) | 146,799 | 1603 | TL201 thallium | 10,313 |

| 750 | Dolasetron mesylate | 137,086 | 4644 | Contrast 100-199 MGs iodine | 9,483 |