U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

National Study of Assisted Living for the Frail Elderly: Literature Review Update

Lewin-VHI, Inc.

February 1996

PDF Version: http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/litrev.pdf (98 PDF pages)

This report was prepared under contract #HHS-100-94-0024 between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy (DALTCP) and Lewin-VHI, Inc. Additional funding was provided by HHS's Administration on Aging. For additional information about this subject, you can visit the DALTCP home page at http://aspe.hhs.gov/_/office_specific/daltcp.cfm or contact the office at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201. The e-mail address is: webmaster.DALTCP@hhs.gov. The Project Officer was Gavin Kennedy.

The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION: BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW OF THE ASSISTED LIVING LITERATURE REVIEW UPDATE

A. The Literature Review for the 1992 Policy Synthesis in Brief

B. The Procedure Used to Assemble the Literature Review Update

C. Findings of the Literature Review Update: A Literature Source Analysis

D. Conclusion

E. The Organization of the Literature Review Update

II. AN OVERVIEW OF ASSISTED LIVING: WHAT IS ASSISTED LIVING?

A. Definitions of Assisted Living at the Time of the 1992 Policy Synthesis

B. Current Definitions of Assisted Living

C. Suggested Typologies for Classifying the Range of Assisted Living Facilities

D. The Size and Growth of the Assisted Living Industry

III. ASSISTED LIVING -- PEOPLE, SETTINGS, AND SERVICES

A. People, Settings, and Services Described in the 1992 Policy Synthesis

B. Resident Profiles in Assisted Living Facilities and Admission and Discharge Criteria

C. Architecture as an Important Component of the Assisted Living Philosophy

D. The Services Provided by Assisted Living Facilities

E. Needs Assessments and Reevaluations

F. Staffing Needs and Staff-to-Resident Ratios in Assisted Living Facilities

IV. THE EFFECTIVENESS AND COSTS OF ASSISTED LIVING

A. 1992 Policy Synthesis Findings Regarding the Effectiveness and Costs of Assisted Living

B. The Current Literature on the Effectiveness of Assisted Living

C. Current Literature Regarding the Costs of Assisted Living

V. ISSUES AND TRENDS IN REGULATING ASSISTED LIVING

A. Regulatory Activities/Other Types of Residential Facilities for the Frail Elderly

B. Regulatory Activity Regarding Assisted Living Emerging from the States

C. Model Regulations and Accreditation

VI. FINANCING

A. Public Financing Programs and Issues Discussed in the 1992 Policy Synthesis

B. New Public Initiatives

C. Private/Public Initiatives

D. Private Initiatives

E. Emerging Issues and Concerns Regarding Financing

APPENDIX A. BIBLIOGRAPHY

LIST OF EXHIBITS

EXHIBIT 1.1: Content Analysis of Literature Since the 1992 Policy Synthesis

EXHIBIT 2.1: Formal Association Definitions of Assisted Living

EXHIBIT 2.2: Definitions of Assisted Living Used by Various Researchers in the Field

EXHIBIT 2.3: Definitions of Assisted Living from the Literature

EXHIBIT 3.1: Services Provided in Assisted Living Facilities

EXHIBIT 3.2: A Comparison of Residents' Need for Assistance

EXHIBIT 3.3: Admission and Retention Policies and Presence of at Least One Current Tenant with Selected Problems in 63 Assisted Living Settings

EXHIBIT 3.4: Reasons for Leaving Assisted Living Facilities

EXHIBIT 3.5: A Comparison of the Percentage of Facilities with Autonomy Enhancing Features from Two Studies -- in Percentage

EXHIBIT 3.6: Core Services Provided by Assisted Living Facilities: in Percentage of Facilities

EXHIBIT 3.7: Board and Care Survey Findings Regarding Services: in Percentage of Facilities, Both Licensed and Unlicensed

EXHIBIT 3.8: Other Services and Amenities Provided by Assisted Living Facilities: in Percentage of Facilities

EXHIBIT 3.9: Services Described in Non-Survey Literature Sources

EXHIBIT 3.10: Staffing Patterns in Four Major Surveys

EXHIBIT 3.11: Current Policy and Most Recent Policy Changes Made by State Legislatures

EXHIBIT 3.12: Issue-Specific Comparison of State Policies

EXHIBIT 4.1: Costs to Residents for Assisted Living

EXHIBIT 5.1: Selected Changes in Licensure Standards for "Residential Care Facilities" 1990-1993

EXHIBIT 5.2: Status of Legislative Activity in Each State

EXHIBIT 6.1: Recent State Financing Policy Changes

I. INTRODUCTION: BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW OF THE ASSISTED LIVING LITERATURE REVIEW UPDATE

"Assisted living" is a term that generally refers to a type of care that combines housing and supportive services in a "homelike" environment and that strives to maximize the individual functioning and autonomy of residents. This document provides a review of published and unpublished literature on assisted living for the period 1992 through September, 1995. This literature review serves as an update to a review of the literature conducted for the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) in 1992. Like its predecessor, this review focuses on assisted living for the frail elderly.

This chapter provides a summary of the 1992 Policy Synthesis literature review, including the origin of the literature review and a discussion of the policy concerns that make assisted living for the frail elderly an increasingly important issue. A description of how the review update has been conducted, what it has yielded in numbers of articles and content, and how it has been organized are also provided in this chapter.

A. THE LITERATURE REVIEW FOR THE 1992 POLICY SYNTHESIS IN BRIEF

In 1992, Lewin-VHI conducted a Policy Synthesis on Assisted Living For the Frail Elderly for the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), hereafter referred to as the 1992 Policy Synthesis. The 1992 Policy Synthesis was undertaken because of policy concerns generated by a growing frail elderly population, a rapid increase in costs of delivering long-term care to that population, and growing interest in various types of supportive housing for the elderly as a potentially desirable arrangement for both housing and service delivery.

Between 1990 and 2030, the U.S. elderly population is expected to double to a total of 65 million people, an estimated 7.3 million of whom will be frail elderly. Costs of nursing home care for the elderly, both in public and out-of-pocket costs, are estimated to grow to more than $100 million annually by 2020. The special combination of housing and supportive services that characterize assisted living is identified with greater independence and dignity for the frail elderly and is bringing the fledgling assisted living industry national attention. Because of its unique physical and philosophical characteristics, assisted living may be a preferred living option for the frail elderly and, at least for some - - a less expensive alternative to nursing homes.

The 1992 Policy Synthesis was based on a review and analysis of over 350 books, reports, documents (both published and unpublished), and telephone interviews with related association representatives, policymakers, academics, and researchers. The 350 items in the 1992 bibliography span 15 years and include material on a wide range of housing options for the frail elderly. At the time that the original report was written, there were relatively few articles and reports available specifically concerning assisted living.

One result of the rapid evolution of the assisted living industry has been the voluminous increase in the number of articles and books published specifically on the topic in the years since the policy synthesis was produced. This literature review update identified 175 articles and reports related to assisted living. Although most of the 1992 literature was indirectly related to assisted living, most of literature included in this update is directly related to assisted living.

B. THE PROCEDURE USED TO ASSEMBLE THE LITERATURE REVIEW UPDATE

To conduct this literature review update, we began with an automated search of seven databases: 1) AgeLine; 2) EM Base; 3) Health Periodicals; 4) Health Plan Administration; 5) Medline; 6) Psychinfo; and 7) the Trade and Industry Index. Key words used for the database searches were: assisted living, congregate housing, board and care home, and domiciliary care. Additional automated searches were conducted by specifying the names of publications that are known to feature articles on assisted living (e.g., Provider, Spectrum, and Contemporary Long-Term Care). In addition, studies mentioned in that literature and reference lists from articles identified in the computer searches were used to identify additional sources. Finally, we asked members of our Technical Advisory Panel to help us identify articles and reports.

C. FINDINGS OF THE LITERATURE REVIEW UPDATE: A LITERATURE SOURCE ANALYSIS

We identified 175 articles and reports published or issued between January, 1992 and September, 1995. To assess recent trends in the literature, we classified the articles into nine categories, based on the source of the article: newspaper articles, provider trade publications, other trade publications, empirical research in peer-reviewed journals, consumer oriented publications, newsletters related to health and/or housing, public relations releases, business journals, and other sources (see Exhibit 1.1).

Growing interest in assisted living is illustrated by an accelerating rate of publication. We identified 108 articles and reports in the three years from January 1992, to January 1995; but we found 67 articles and reports published or issued in just the first nine months of 1995. The majority of articles (32 percent) identified since 1992 were found in provider trade publications. The second largest category of articles is "Other Sources." This category includes reports (not yet submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals) by consultants and research organizations that typically perform "leading edge" work. The third largest category is "Other Trade Publications" (e.g., The Consultant Pharmacist ) (15 percent). "Empirical Research in Peer-Reviewed Journals" makes up the fourth largest category (10 percent).

| EXHIBIT 1.1: Content Analysis of Literature Since the 1992 Policy Synthesis | |||

| Literature Source | Number of Items: Jan 1992-Jan. 1995 | Number of Items: January-September 1995 | Total Number (% of total) |

| Newspaper Articles | 5 | 5 | 10 (6) |

| Provider Trade Publications | 30 | 26 | 56 (32) |

| Other Trade Publications | 21 | 6 | 27 (15) |

| Empirical Research in Peer-Reviewed Journals | 14 | 3 | 17 (10) |

| Consumer Oriented Publications | 3 | 0 | 3 (2) |

| Books or Newsletters Related to Health and/o r Housing | 9 | 4 | 13 (7) |

| Public Relations Releases | 4 | 4 | 8 (5) |

| Business Journals | 7 | 3 | 10 (6) |

Other Sources:

| 15 | 16 | 31 (18) |

| Total | 108 | 67 | 175 (100) |

| NOTE: Individual line percentages do not equal 100 percent due to rounding. | |||

Closer examination of the literature in the provider trade publication category, the largest of the nine categories, indicates that these articles are concerned largely with financing and the future of the industry. Fourteen of the provider trade publication articles focus on financing, another six articles review the benefits of Medicaid waivers and third-party reimbursement, six more articles are concerned with regulations, and five articles explore the future of the industry, particularly considering the growing influence of managed care.

Articles drawn from the empirical literature provide some of the most valuable information of all of the sources. The empirical literature includes various reports on the assisted living industry in general and two studies of health care utilization among those living in Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs) or assisted living facilities (Newcomer & Preston, 1994; Newcomer, Preston, & Roderick, 1995).

Articles included in the category "other trade publications" (i.e., from other than assisted living provider trade publications) are oriented to the insurance, architecture, and real estate industries. The insurance industry is concerned with long-term care insurance coverage of assisted living (Koco, 1992; Koco, 1994) and the real estate industry finds value in assisted living facilities as investment opportunities (Kramer, 1994, Real Estate Weekly, 1994).

D. CONCLUSION

The update review of the literature published since 1992 indicates a heightened interest in assisted living. In general, the articles written over the past two to three years have become increasingly more specific and more exhaustive of the subject of assisted living. Opportunities for HUD Section 232 financing and Medicaid waivers have inspired many of the recent articles and reports. In addition, research on the needs of dementia patients and "best practices" research on living arrangements for the frail elderly in general have also had an impact on recent writing on assisted living. However, a general consensus in the literature regarding definitions of assisted living and its attendant services and amenities continues to be lacking.

E. THE ORGANIZATION OF THE LITERATURE REVIEW UPDATE

With one exception, the chapter headings and topics used in the 1992 Policy Synthesis provide a structure for the literature review update. The exception is the chapter on the frail elderly and their living arrangements, which has been omitted from the update. Each chapter in the following report includes a brief summary of findings from the 1992 Policy Synthesis followed by analyses of more recent articles.

Chapter Two provides an overview of assisted living. This chapter follows the evolution of the term assisted living from the time of the 1992 Policy Synthesis to the present. It also focuses on the issues involved in defining the term assisted living, and the kinds of boundaries that may be relevant for establishing a formal definition.

Chapter Three addresses the issues of people, settings, and services. Both assisted living residents and staff are mentioned frequently in the literature covered in this chapter. In addition, we discuss the importance of environment and physical structure to the concept of assisted living. We also explore whether there is a minimum set of core services for assisted living facilities, and the extent to which these are scheduled versus non-scheduled services. The degree to which skilled nursing and ancillary services are provided is another topic of importance. Finally, the literature coverage of initial needs assessments and reevaluations is discussed.

Chapter Four addresses the issues of the effectiveness and costs of assisted living. Advocates of assisted living have maintained that assisted living facilities are a less expensive alternative to nursing homes. Empirical studies support the notion that assisted living may contribute to a different way of utilizing the health care system. This chapter also discusses different models of pricing assisted living that have developed over time, as well as the actual costs to the consumer that have been reported in the literature.

Chapter Five addresses issues involved in regulating assisted living. We focus on the contentious question of the need for industry regulation (with some attention given to the ability of the industry to self-regulate through a formalized accreditation process) and we review recent state regulatory changes. Recent changes in Certificate of Need (CON) regulations and the introduction of Medicaid waiver programs are both important topics addressed in this chapter.

Chapter Six addresses the issue of financing assisted living. Both new public initiatives and public/private initiatives are discussed in this chapter. In particular, the implications of the HUD Section 232 Mortgage Insurance Program and other new changes in institutional lending for assisted living facilities are reviewed.

II. AN OVERVIEW OF ASSISTED LIVING: WHAT IS ASSISTED LIVING?

In this chapter we provide an overview of assisted living. We discuss the conventional definition(s) of the term "assisted living" prior to the 1992 Policy Synthesis and the evolution of the term since that time. This chapter also addresses the fundamental problems in reaching a common understanding of the physical and philosophical characteristics of assisted living as well as developing profiles of assisted living residents and staff.

A. DEFINITIONS OF ASSISTED LIVING AT THE TIME OF THE 1992 POLICY SYNTHESIS

The 1992 Policy Synthesis found that the term "assisted living" was broadly used to refer to housing for the elderly with supportive services in a homelike environment. No precise definition of assisted living had developed at the time of the 1992 Policy Synthesis. In addition, other terms used to describe similar packages of services (e.g., board and care and residential care) were often used interchangeably with assisted living. At the time the 1992 Policy Synthesis was completed, federal regulations generally included assisted living facilities under the term "board and care." Most states did not use the term "assisted living" except in reference to programs for persons with mental retardation and related conditions.

Although the 1992 Policy Synthesis determined that the definition of assisted living was similar to that of board and care, the proponents of assisted living at the time asserted that a special philosophy distinguished assisted living from board and care. That philosophy was said to embody a set of principles regarding such things as maximizing the functional capability and the autonomy of the individual resident. These principles included using the environment as an aid to both independence and socialization.

By 1992, two views of the role of assisted living in long-term care had emerged. Some viewed assisted living as a type of service on a "continuum" from home care to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). Others, those who advocate for "aging in place," saw assisted living as an approach and philosophy of care and living that could serve the needs of a very broad range of people (including those needing skilled nursing).

B. CURRENT DEFINITIONS OF ASSISTED LIVING

1. Trade Association and Organization Definitions

In the past three years, several trade associations affiliated with the assisted living industry and a number of research and policy organizations have developed formal definitions of assisted living. Exhibit 2.1 presents the formal definitions of the Assisted Living Facilities Association of America (ALFAA), the American Seniors Housing Association (ASHA), the American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging (AAHSA), the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the National Academy of State Health Policy, National Association of Residential Care Facilities, and the National Association of State Units on Aging (NASUA).

| EXHIBIT 2.1: Formal Association Definitions of Assisted Living | |

| Association | Definition |

| American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging (AAHSA) | "Assisted living is a program that provides and/or arranges for the provision of daily meals, personal and other supportive services, health care, and 24 hour oversight to persons residing in a group residential facility who need assistance with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. It is characterized by a philosophy of service provision that is consumer driven, flexible, individualized and maximizes consumer independence, choice, privacy, and dignity." |

| Assisted Living Facilities Association of America (ALFAA) | "Assisted living is a special combination of housing, supportive services, personalized assistance and health care designed to respond to the individual needs of those who need help in activities of daily living. Supportive services are available, 24 hours a day, to meet scheduled and unscheduled needs, in a way that promotes maximum independence and dignity for each resident and encourages the involvement of a resident's family, neighbors, and friends." |

| American Seniors Housing Association (ASHA) | "A coordinated array of personal care, health services, and other supportive service s available 24 hours per day, to residents who have been assessed to need those services. Assisted living promotes resident self direction and participation in decisions that emphasize independence, individuality, privacy, dignity, and residential surroundings." |

| American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) | The following operational definition was used for the AARP's 1995 publication titled "Assisted Living and Its Implications for Long-Term Care" by Elizabeth Clemmer: "group or congregate living arrangements that provide room and board as well as social and recreational opportunities; assistance to residents who need help with personal needs and medications; availability of protective oversight or monitoring; and help around the clock and on an unscheduled basis." |

| US Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), Medicaid Home and Community Based Waiver 1915(c) | Assisted living is one of two categories of Adult Residential Care under a 1915(c) waiver. It is defined as: Personal care and services, homemaker, chore, attendant care, companion services, medication oversight (to the extent permitted under State law), therapeutic social and recreational programming, provided in a licensed community care facility, in conjunction with residing in the facility. This service includes 24 hour on site response staff to meet scheduled or unpredictable needs and to provide supervision of safety and security. Other individuals or agencies may also furnish care directly, or under arrangement with the community care facility, but the care provided by these other entities supplements that provided by the community care facility and does not supplant it. Care is furnished to individuals who reside in their own living units (which may include dually occupied units when both occupants consent to the arrangement) which may or may not include kitchenette and/or living rooms as well as bedrooms. Living units may be locked at the discretion of the client except when a physician or mental health professional has certified in writing the client is sufficiently cognitively impaired as to be a danger to self or others if given the opportunity to lock the door. (This requirement does not apply where it conflicts with the fire code.) Each living unit is separate and distinct from each other. The facility must have a central dining room, living room or parlor, and common activity center(s) (which may also serve as living rooms or dining rooms). Routines of care provision and service delivery must be client-driven to the maximum extent possible. Assisted living services may also include:

However, nursing and skilled therapy services are incidental, rather than integral to the provision of assisted living services. Payment will not be made for 24-hour skilled nursing care or supervision. FFP is not available in the cost of room and board furnished in conjunction with residing in an assisted living facility. Payments for adult residential care services are not made for room and board, items of comfort or convenience, or the costs of facility maintenance, upkeep, and improvement. Payment for adult residential care services does not include payments made, directly or indirectly, to members of the recipient's immediate family. |

| US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) | Assisted living means a public facility, proprietary facility, or facility of a private nonprofit corporation that is used for the care of the frail elderly, and that:

|

| National Academy of State Health Policy | NASHP declined to provide one concise definition of assisted living. However, extensive commentary on all aspects of services, admission and discharge criteria, and site standards make the "Guide to Assisted Living and State Policy" a definition in itself. |

| National Association of Residential Care Facilities | Residential care facility means a home or facility of any size, operated for profit or not-for-profit, which undertakes through its owner/s or management to provide food, housing and support with activities of daily living and/or protective care for two or more adult residents not related to the owner or administrator. Residential care homes are also known as assisted living facilities, foster homes, board and care homes, sheltered care homes, etc. |

| National Association of State Units on Aging (NASUA) | NASUA subscribes to a definition of assisted living which acknowledges the deep desire of America's elders to reside in their own homes or in a homelike environment. Accordingly, the Association views assisted living as referring to a homelike congregate residence providing individual living units where appropriate supportive services are provided through individualized service plans. Assisted living is first and foremost a home in which residents' independence and individuality are supported and in which their privacy and right to self-expression are respected. |

Most of the definitions from the nine organizations listed above refer to the "aging-in-place" philosophy of assisted living. The central tenet of that philosophy, the notion that the resident's dignity and autonomy are paramount, is made clear in most of these definitions. For example, the AARP definition emphasizes that the "aim of assisted living is to enhance the capabilities of frail older persons so that they can live as independently as possible in a home-like atmosphere. Assisted living accomplishes this through both building design and care practices that facilitate independent functioning and reinforce residents' autonomy, dignity, privacy, and right to make choices" (Clemmer, 1993).

The definitions from AAHSA, AARP, ALFAA, ASHA, and HCFA all specify that supportive services should be available 24-hours a day. The 24-hour requirement is significant because it indicates a facility's commitment to respond to unscheduled needs for assistance. In contrast, the National Association of Residential Care Facilities and HUD definitions do not mention any tenets of the assisted living philosophy nor do they specify when supportive services should be available.

2. Assisted Living/Seniors Housing Experts Definitions

Experts in the assisted living field increasingly include mention of a special assisted living philosophy in their working definitions (see Exhibit 2.2). Tangible evidence and results of this philosophy (e.g., "the dignity of risk" or "individual choice") are very difficult to quantify in survey research. In recognition of this, Kane and Wilson, two of the researchers most identified with the idea that assisted living includes a special philosophy of care, used a minimalist definition in their 1993 study for AARP.

| EXHIBIT 2.2: Definitions of Assisted Living Used by Various Researchers in the Field | |

| Researcher | Definition |

| Rosalie A. Kane & Robert L. Kane, 6/7/95, JAMA | "One attractive emerging option is assisted living, which under some state licensure features single-occupancy apartment units with full bathrooms and kitchenettes. Such programs serve three meals a day and provide on-site staff. Individually planned care is brought to the consumers' own apartments." |

| Rosalie A. Kane & Keren Brown Wilson, 1993, Assisted Living in the United States | "Assisted living is any group residential program that is not licensed as a nursing home, that provides personal care to persons with need for assistance in the activities of daily living (ADL), and that can respond to unscheduled need for assistance that might arise." |

| Victor A. Regnier, 1994, Assisted Living Housing for the Elderly | "Assisted living is a long-term care alternative which involves the delivery of professionally managed personal and health care services in a group setting that is residential in character and appearance in ways that optimize the physical an d psychological independence of residents." |

| Joann Hyde, 1995, draft report of People With Dementia: Toward Appropriate Regulation of Assisted Living and Residential Care Settings | "Assisted living is a service-rich residential environment designed to enable individuals with a range of capabilities, disabilities, frailties and strengths to reside in a homelike setting as long as possible." |

| Donna Yee, August 1995, cited in Currents in reference to a Brandeis University study. | Assisted living is defined in the study as "programs that offer congregate housing and supportive services with explicit or implicit commitment to respond to individual preferences for help with health-care access, personal care and household maintenance." |

3. General Article Definitions

A number of the general articles identified from 1992 to 1995 also provide definitions of assisted living. These definitions are found in Exhibit 2.3, where they are organized by date. In general, definitions appear to build on past work in a field, and this literature review update is no exception. One can follow the progressive development over time of the definition from a very vague listing of services to a much richer treatment of the philosophy of assisted living. While one might expect to observe a convergence on the definition of assisted living used in the literature, this has not yet been the case.

Assisted living is described in most provider trade publications as a residential option for the elderly who need some help with activities of daily living (ADLs) and possibly some minimal nursing care. Most definitions from the literature refer to the provision of supportive personal care services and many explicitly mention either that assisted living residents do not require the intensity of care found in nursing homes or that residents have "limited medical needs" or require "minimal medical care."

| EXHIBIT 2.3: Definitions of Assisted Living from the Literature | ||

| Date | Source = Author & Publication | Definition |

| 12/4/92 | McCarthy, Wall Street Journal | "A new style of housing for frail elderly people who don't have serious medical problems." |

| 1/3/93 | Diesenhouse, NY Times | "Usually small developments (that) consist of private or semiprivate apartments, from studios with no kitchens to fully equipped one or two bedrooms...help (is) provided to residents in the form of housekeeping and meal services and minor medical care. Also provided is personal care such as getting out of bed, bathing, and dressing." |

| 1/3/93 | Stuart, NY Times | "Residents live independently...while receiving 24-hour supervision, assistance in daily living, meals, housekeeping, transportation, and recreational programming. Minimum health care or nursing assistance is provided as needed." |

| 2/93 | Rajecki, Contemporary Long Term Care | Housing and Community Development Act of 1992: Assisted living facilities are "public, proprietary or private/nonprofit facilities that: Are licensed and regulated by the state; make available to residents supportive services to assist residents in carrying out activities of daily living; and provide separate dwelling units for residents, each of which may contain full kitchen and bathroom." |

| 4/93 | PR Newswire | "Service-intensive housing for ...frail but functional seniors." |

| 8/6/93 | Garbarine, New York Times | "Hotel style rental project for elderly people who may need help with daily chores but do not need constant medical care." |

| 8/93 | Provider | Residential care setting "noted for its low-cost, homelike environment for individuals needing limited assistance and falls on the continuum between boarding homes and skilled nursing facilities. It is a social model of health care that maximizes independence while providing limited non-medical care and services." |

| 8/93 | Geran, Interior Design | Describes a CCRC " Assisted Living unit where nursing staff and doctors provide medical care." |

| 1993 | Older Women's League | Assisted living "covers a wide range of licensed an d unlicensed facilities: residential care facilities, adult congregate living facilities, personal care homes, retirement homes, board and care homes. These facilities offer housekeeping, meal services, personal care and minor medical care." |

| 1/94 | Walser, Harvard Health Letter | One of three types of care provided in continuing care retirement communities; a type of care for seniors "needing help getting out of bed, bathing, dressing, eating, walking, or going to the bathroom." ALFs provide access to 24-hour help. |

| 2/94 | Riegel, New Orleans Magazine | "Designed for the elderly who are still able to care for themselves....They offer pleasant, safe surroundings in which the elderly can live independently. But they also provide such services as nursing care, transportation and housecleaning as needed." |

| 3/94 | Kramer, Pension World | "A senior-living complex with physical feature s designed to assist the frail elderly, with staff personnel and programs that assist residents with the activities of daily living." |

| 6/5/94 | Cerne, Hospitals & Health Networks | "Suited for patients who, for a variety of reasons, cannot live alone but don't need the 24-hour skilled medical care provided by nursing homes." |

| 4/2/94 | Davis, Milwaukee Business Journal | Assisted living draws from two populations: 1) people who do not require continuous medical care, but occasionally need someone to help them get dressed, or to remind them to take medication" and 2) "healthy and active seniors who simply want to shed some of the burdens of home ownership." |

| 6/5/94 | Cerne, Hospitals & Health Networks | "Suited for patients who, for a variety of reasons, cannot live alone but don't need the 24-hour skilled medical care provided by nursing homes." |

| 7/7/94 | PR Newswire | Subsumed under congregate housing; "typically provide three daily meals and personal care as needed." |

| 8/15/94 | Wilson, Brown University Long term Care Quality Letter | "An alternative model of supportive housing.... In Oregon, private apartments are shared only by choice. Everyone agrees that assisted living should provide at least congregate services (meals, housekeeping, laundry, transportation, group activities)." |

| 8/94 | Building Design & Construction | "A communal residence for senior citizens who don' t require the 24-hour care of nursing homes, but who nevertheless need some assistance with the activities of daily living." |

| 1/5/95 | Pressler, Washington Post | "Bed-and-breakfast-like homes provide senior citizens with shared or private apartments, meals in a communal dining room, daily housekeeping services and limited medical care." |

| 12/94 | Folkemer, Intergovernmental Health Policy Project | "A care option generally designed around individualized service contracts and "managed risk." |

| 1/95 | Pfeiffer, Postgraduate Medicine | "Residential facilities that provide supervision and care for individuals who have lost some degree of self-care capacity...these facilities fill a niche between independent living arrangements and the full supervised care offered in nursing homes." |

| 1/9/95 | Vick, The Washington Post | "Assisted living facilities grew out of boarding homes -social places-and have prospered by offering the "frail elderly" greater independence in exchange for less security than assured by the rigid, essentially medical boarding of a nursing home." "What the industry calls 'assisted living,' the state knows variously as 'board and care,' 'sheltered living,' 'protect homes,' and 'domiciliary care,' either 'registered' or 'licensed.'" |

| 1-2/95 | Chisholm and Hahn, Geriatric Nursing | "Domiciliary care is a residential rehabilitation and health maintenance center for veterans who are ambulatory and can care for themselves, but who because of medical or psychiatric disabilities are unable to live independently. They reside in a structured, therapeutic, homelike environment." |

| 2/95 | Olson, Provider | "An ALF (assisted living facility) is defined by HUD as a not-for-profit or for-profit facility for the frail elderly that is licensed and regulated by the state, or, if there is no state law providing for such licensing and regulation, by the municipality or other political subdivision in which the facility is located. The ALF may be freestanding or a part of a complex of other facilities." |

| 4/19/95 | Business Wire | "Assisted living apartments are provided for people who need occasional to frequent help with activities of daily living." |

| 4/28/95 | Bruck and Widdes, Tampa Bay Business Journal | "The concept is simply to make senior citizens feel like they are at home rather than in an institution. The dwellings provided by the company come with a yard, a porch and a kitchen. Residents are encouraged to eat in a common dining area, which doubles as a game room and meeting area." |

| 5/95 | Braga, Nursing Homes | "there are few, if any, alternatives for patients in the middle of the spectrum-those who are unable to live independently, yet don't require skilled nursing care...because assisted living residences are not bound by the same regulations that govern nursing homes, we have the opportunity to be more flexible and creative with respect to physical environment and delivery of services....Each facility houses 50 to 60 residents, yet has a cozy, informal environment that is as home-like as possible." |

| 6/23/95 | PRNewswire | "Assisted living is an alternative lifestyle for individuals not requiring the medical surroundings of nursing home care." |

| 8/8/95 | PR Newswire | "Assisted living services provide greater opportunities for seniors to live independently through a selection of services such as assistance at meal time or wit h bathing." |

Although there is some recognition of the significance of physical environment in assisted living (Diesenhouse, Rajecki, Provider, Riegel, Kramer, Wilson, Pressler, Chisolm and Hahn, Bruck and Widdes, and Braga), there is less indication in the literature of a general understanding of the assisted living philosophy. Only the articles authored by Folkemer, Vick, Braga, and the editors of Provider, are explicit in their explanations of the importance of preserving the dignity and independence of assisted living residents through architectural and design strategies.

Despite similarities among the association definitions and the literature definitions of assisted living, there is little consensus concerning the details of care provision and the importance of an assisted living philosophy of care.

C. SUGGESTED TYPOLOGIES FOR CLASSIFYING THE RANGE OF ASSISTED LIVING FACILITIES

The 1992 Policy Synthesis classified assisted living facilities into three types: public housing, units in continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs), and freestanding facilities. This classification system was used because the available data and information were organized in this fashion.

Another typology, conceptualized by Lawton (1977; 1980) and further explained by MacDonald, Remus, and Laing's (1994) research with a small sample of elderly, contrasts "constant" and "accommodating" models of health and housing that can be used with assisted living. The constant model entails admission and discharge policies and procedures developed by management personnel. The environment facilitates resident independence, but does not change over time. The accommodation model is similar to an "aging in place" model where the environment changes over time and residents stay in the facility until they need 24-hour nursing care. MacDonald and associates conducted focus group interviews with 29 subjects from a random stratified sample to determine the subjects' attitudes toward housing. All subjects emphasized the importance of maintaining their independence and the importance of continuity of care. In attitudes toward housing, however, the researchers found that the subjects divided into two groups, based on health and disability. Those subjects who were in poorer health and who were more disabled favored adding services and modifying the environment, or the accommodating model. Those in better health and less disability favored the constant model where services provided and the environment would remain constant over time.

Heumann and Boldy (1993) have used another typology to classify international models of assisted living for low income and frail elderly. This typology has two primary categories: 1) "predisposing conditions" and 2) "environmental dimensions." Predisposing conditions are further divided into four secondary characteristics: 1) social values under which programs are conceived; 2) the extent of government resource commitment; 3) government operational level; and 4) the mix of program ownership and management, public or private. Social values includes four subcategories, ranging from the rejection model, the social service model, and the participation model, to the self-actualization model. Environmental dimensions have two secondary characteristics: 1) program support emphasis and 2) lifestyle emphasis. The program support emphasis is further categorized into four continua, ranging from the housing to community service focus, conventional to sheltered housing design, visiting to on-site service delivery, and incremental to holistic management. Lifestyle emphasis assesses the extent to which the neighborhood and facility are segregated or integrated by age and whether the units are private or communal. In an earlier work, Heumann and Boldy (1982) developed a way of categorizing and simplifying program variations by using three continua describing levels of services, privacy, and community sizes, respectively. The service continuum ranges from the minimal service model with no on-site support to the service rich model with full on-site services, including nursing staff. The privacy continuum ranges from a model with conventionally designed private units with no communal space to a model with only bedrooms remaining private. The size continuum ranges from one to ten units, which makes support staff costs prohibitive, to multiples of 100 plus units managed by a bureaucracy.

A typology developed by Gold and associates (1991) for nursing home special care units for seniors with cognitive impairment rates facilities dichotomously on 27 key variables, many of which are subjective (e.g., inside ambiance). The authors maintain that "each type represents a unique, model constellation of patient care, staff, and administrative characteristics of the settings included in it" (Gold et al., 1991, p. 470). The typology includes eight categories, including "ideal, uncultivated, heart of gold, rotten at the core, institutional, limited, conventional, and execrable."

An additional typology has been introduced by Mollica et al. in their May 1995 report for the National Academy for State Health Policy. The three models identified in that study were "institutional or board and care," a new "housing and services" model, and a "purely service-oriented" model. In the first model, aging-in-place is addressed in both traditional board and care facilities and in frail elderly housing projects. Facilities that fit into this model have residents with a range of ADL and other service needs; some residents may be totally independent and others may require significant assistance with ADLs. States which separate the housing and service components of assisted living provide greater flexibility to residents seeking to age-in-place, but they do not address the institutional character of traditional board and care facilities that still exist in many states. The service delivery model licenses or contracts with the agency providing assisted living services that may be provided in housing settings. Mollica et al. (May, 1995) included a chart in their report which classifies states according to the model that best characterizes current state policy. (See Exhibit 5.2 in Chapter 5 of this document.)

D. THE SIZE AND GROWTH OF THE ASSISTED LIVING INDUSTRY

The lack of a generally accepted definition of assisted living and lack of systematic counting of those facilities in large government surveys currently preclude precise counts of the current number of assisted living facilities, the current assisted living resident population, and the extent of industry growth.

Although the literature published since 1992 contains assertions that the number of assisted living facilities is increasing (e.g., Buss, 1994; Gamzon, 1993; Cook, January 1995; Nichols, January 1995; Vick, January 9, 1995; Currents, May 1995; Evans, September 18, 1995; Kane, 1995) there has been little concrete data available to assess growth systematically.

A 1993 "Overview of the Assisted Living Industry," produced by ALFAA and Coopers & Lybrand reports that "there may be as many as 65,372 Assisted Living Type facilities, housing between 104,803 and a million residents, depending on how assisted living is defined." The sources cited by the Overview include a 1992 study by Coopers & Lybrand and the 1992 Policy Synthesis. The 1992 Policy Synthesis estimate, from which the number of units mentioned above is taken, is drawn from a 1990 study of all potential licensed board and care facilities conducted by Lewin-ICF for ASPE. (This study did not count unlicensed board and care homes.) A number of articles included in this literature review update cite the Lewin-VHI 1992 Policy Synthesis or the 1993 ALFAA Overview. Thus, estimates of assisted living facilities appear to be circular rather than systematic.

Modern Healthcare, a trade publication, has conducted at least two surveys of multi-unit providers. Results indicate an increase of six percent in CCRCs operated by respondents to the survey from 1992 to 1993 (Pallarito, 1994). The survey reports on the number of CCRCs, as well as independent living, assisted living, and nursing home beds. Of the 87 entities reporting, 21 increased the number of their assisted living beds, while seven decreased the number of their assisted living beds. The total number of assisted living beds in 1993 among these 87 CCRCs was 12,369. Pallarito's 1995 article in Modern Healthcare titled "Assisted Living Captures Profitable Market Niche," indicates that there may be somewhere between 30,000 and 40,000 assisted living providers today.

A recent Consultant Pharmacist article similarly estimates that there are between 40,000 and 65,000 providers serving one million people. This article cites estimates that the assisted living target population is expected to increase sixfold over the next 25 years, when a large portion of the baby boom generation enters their seventies. It also cites predictions that more than seven million frail elderly persons will be candidates for assisted living by the year 2020 (Nichols, January, 1995). The Washington Post has also reported "industry estimates" of 40,000 assisted living providers in the United States, serving 1 million people. The Post, reflecting interviews with those in the industry, notes that the industry is expected to grow to serve three times that number of older people within the next ten years. Other experts have predicted that the industry will grow to become a $25 billion-revenue producing industry by the year 2000 (J. Baker, as cited in Pallarito, 1995).

III. ASSISTED LIVING -- PEOPLE, SETTINGS, AND SERVICES

This chapter focuses on the people, settings, and services of assisted living. We discuss resident profiles and review the literature in terms of admission and discharge conventions for assisted living residents. In addition, we summarize the literature on staff profiles for both professional and non-professional employees of assisted living facilities, review the literature concerning the importance of the physical environment in the philosophy of assisted living, and review the types of services that the literature associates with assisted living care packages. Furthermore, we investigate whether these services are described as scheduled or non-scheduled, bundled or unbundled. The presence or absence of skilled nursing and ancillary services and the scheduling of those kinds of services are additional issues addressed in the literature which we note in this chapter.

A. PEOPLE, SETTINGS, AND SERVICES DESCRIBED IN THE 1992 POLICY SYNTHESIS

1. Admission Criteria

The 1992 Policy Synthesis found that there was little agreement in the literature on eligibility conventions for assisted living residents or on the person or persons who should make those kinds of determinations. The literature generally indicated that assisted living was appropriate for medically stable individuals who did not require 24-hour nursing supervision or professional medical care. However, many authors disagreed about whether cognitively impaired seniors or individuals with a number of physical disabilities would be best served in assisted living facilities.

The 1992 Policy Synthesis identified three central criteria used in screening new applicants for assisted living: income, age, and functional capability. Public facilities targeted low income populations, while non-public facilities appeared to target wealthier seniors. With respect to age, we found that: HUD had no age eligibility restrictions; most state-funded programs were limited to residents over 60 years old; and a number of CCRCs were limited to residents over 62 years old, while other CCRCs were limited to 65 years as a minimum age. Criteria on functional disability ranged widely, depending on the type of facility and/or the location of the facility. For instance, in 1992, HUD's Congregate Housing Services Program (CSHP) required that residents need assistance in three or more ADLs/IADLs, including eating or preparing meals and must have no informal support network (Struyk, 1989). Although most state-funded facilities required that seniors have impairment in at least one ADL task, Massachusetts and New Jersey admitted seniors who were socially isolated but functionally intact. The 1992 Policy Synthesis pointed out that the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988, by including disabled individuals as a group protected from housing discrimination, and the Americans with Disabilities Act could have significant ramifications for assisted living and could have a direct effect on eligibility requirements.

The 1992 Policy Synthesis determined that transfer decisions appeared to be made systematically within assisted living facilities but the parties responsible for making transfer decisions varied between facilities. For instance, in public facilities housing managers generally performed the initial assessments, while in CCRCs and private assisted living facilities case managers were more likely to perform initial screening assessments. In some CCRCs and private facilities, a facility physician or nurse performed the assessment.

2. Services

Services provided by assisted living facilities varied widely across facilities, as shown in Exhibit 3.1, which is taken from the 1992 Policy Synthesis. This table synthesizes services provided in four surveys: 1) a survey of Section 202 Housing (Gayda & Heumann, 1989); 2) a seven state survey of 602 non-Medicaid certified facilities (Moon et al., 1989); 3) a survey of 200 assisted living facilities (Seip, 1990); and 4) a survey of 10 assisted living facilities in Florida (Kalymun, 1990). These surveys demonstrate that there was little consensus on a core set of services.

3. Staff

The 1992 Policy Synthesis determined that staffing patterns, ratios, and professionalism also varied widely across assisted living facilities. Although it was difficult to generalize, the 1992 Policy Synthesis found that staff roles in assisted living facilities were less differentiated than those found in facilities providing more traditional care. The literature described the following staff positions: housekeepers, kitchen workers, maintenance personnel, transportation staff, and managerial and clerical staff. A 1992 American Health Care Association (AHCA) study found that the average member residential care facility who typically had 50 beds employed 3 management personnel, 5 nurses, 13 aides, 9 dietary staff, and 4 housekeepers. The AHCA member facilities also reported employing a number of other types of staff: an activities director (82 percent), a pharmacy consultant (70 percent), a RN consultant (60 percent), a dietitian (45 percent), a physical therapist (36 percent), and a social worker (46 percent). With regard to staff ratios, Moon (1989) found a mean staffing ratio of 3.2 residents per staff member in the seven states studied with a staff to resident ratio range from 2.8 to 4.7.

| EXHIBIT 3.1: Services Provided in Assisted Living Facilities | ||||

| Author | Gayda and Heumann(1989) | Moon, M., et. al.,(1989) | SEIP(1990) | Kalymun(1990) |

| Sample | Approximately 2,000 Section202 Housing Facilities Across Nation | Seven State Survey of 602 Non-Medicaid Certified Facilities, Licensed or Non-licensed That Provided Room and Board, Personal Care and Protective Oversight to Four or More People | A Survey of 200 Assisted Living Facilities Across the United States | 10 Assisted Living Facilities Certified as Adult Congregate Living Facilities in Florida |

| SERVICES | ||||

| Housekeeping | 18% | 100% | 100% | |

| Transportation | 22% | 65% | 91% | 100% |

| Personal laundry | - | 97% | 100% | |

| Personal Care | 20% | - | - | |

| Grooming | - | 59% | 92% | 100% |

| Dressing | - | 62% | 93% | 100% |

| Bathing | - | 82% | 95% | 100% |

| Toileting | - | 42% | 78% | - |

| 3 Meals/Day | 50% | 97% | 100% | |

| Assist with Medications | - | 96% | 100% | |

| Physical Therapy | - | 71% | - | |

| Psychological Counseling | - | 61% | - | |

| 24-Hour Licensed Nurse | - | 70% | - | |

| * 50 percent of the states offer meals; the number per day is not specified. | ||||

B. RESIDENT PROFILES IN ASSISTED LIVING FACILITIES AND ADMISSION AND DISCHARGE CRITERIA

The literature from 1992 to the present provides some general information about the residents of assisted living facilities, but provides little information about who is eligible, how and by whom eligibility is determined, or who is excluded from assisted living. Most of the information about residents of assisted living facilities comes from two studies: 1) a study by ALFAA and Coopers & Lybrand (1993), reported in An Overview of the Assisted Living Industry and 2) the Kane and Wilson (1993) study of assisted living for the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) reported in Assisted Living in t he United States: A New Paradigm for Residential Care for Frail Older Persons.

The study by ALFAA and Coopers & Lybrand (1993) is a survey of assisted living providers conducted in the Spring of 1993. The data come from 201 facilities, representing 6,119 units in 25 states. For-profit assisted living facilities represented 75 percent of the sample, 4 percent were publicly-held and 21 percent were non-profit.

The Kane and Wilson (1993) study had two components: a national study of assisted living and a study of assisted living in the state of Oregon. The national study included interviews with a national sample of administrators of 63 assisted living facilities; 65 percent of the facilities were for-profit, 35 percent were non-profit programs. In most cases, this study was restricted to facilities with 15 or more residents. Oregon was studied separately because the state has "gone further than any other in defining assisted living through regulations, encouraging purpose-built assisted living programs through incentives for developers, and providing a reimbursement source for the care component of the program" (Kane & Wilson, 1993, p. 51). The Oregon sample includes 20 of the 22 licensed programs in the state with 947 tenants in residence at the time of the study. Data from the national study and the Oregon study are reported separately by Kane and Wilson and are treated separately in this review.

1. Vital Statistics: Average Age, Gender, and Marital Status

The ALFAA study provides a resident profile drawn from the assisted living facilities responding to their survey: 79 percent of residents are female with an average age of 85; male residents average 83 years (ALFAA and Coopers & Lybrand, 1993). In their national study, Kane and Wilson (1993) found that the average age for residents was 83 years. The Oregon residents were predominately female (75 percent) with an average age of 85, and 97 percent were unmarried. In a study of the relationship of assisted living residents to health care utilization, Newcomer and Preston (1994) found that the average age of residents in two CCRCs was 82.2 years and that 76.7 were female. In a second study the average age at entry was 79.3 years and 72.4 percent were female (Newcomer, Preston, & Roderick, in press).

In addition to the aforementioned studies, Coopers & Lybrand in conjunction with the American Seniors Housing Association have produced The State of Seniors Housing 1994 (1995), a project that surveyed senior housing executives in congregate housing, CCRC's, and assisted living facilities for information on financing and development, resident characteristics, and financial performance indicators. This study found that assisted living facilities generally serve a population of single females in their early 80's. The prototypical assisted living resident was an 81.8 year-old female. In fact, only 19 percent of assisted living residents were male, according to the findings of this study.

Finally, the vast majority of residents (more than 97 percent) in these facilities are unmarried or are not living with their spouse.

2. ADL Impairment

The ALFAA study found that assisted living residents have a mean number of 3.06 ADL impairments and 42 percent have some cognitive impairment. They also found that typical residents were females needing "moderate or heavy care." The residents frequently needed help with ambulating, medicines, bathing and/or dressing and were forgetful. Kane and Wilson report that a summary classification scheme used by the State of Oregon to classify Medicaid clients determined that the Oregon sample had more physical and cognitive impairment than the national sample studied by Kane and Wilson, as shown in Exhibit 3.2.

| EXHIBIT 3.2: A Comparison of Residents' Need for Assistance | ||

| Residents' Need for Assistance | National Residents Sample | Oregon Residents |

| Low Need for Assistance | 25 percent | 10 percent |

| Medium Need for Assistance | 50 percent | 61 percent |

| Medium Need for Assistance | 25 percent | 29 percent |

| SOURCE: Kane and Wilson, 1993 | ||

3. Admission and Discharge

a. Factors Influencing Admission and Discharge Patterns

Researchers report in recent literature that, among other things, age at entry into a senior housing facility "significantly affects the likelihood of assisted-living and nursing unit use in all residents' models..." More extensive analysis of admission and discharge patterns between assisted living facilities and nursing units is greatly needed in order to provide a more comprehensive picture of the role that assisted living plays in the larger chronic care industry, and to inform interested parties about the impact of transfers on total costs. The effect of transfers on residents' health care utilization will be discussed in the section on effectiveness of assisted living (Newcomer, Roderick, and Preston, June 1995).

The development of widely applicable admission and discharge criteria is an important issue facing the assisted living industry. Some industry experts believe that as much as 20 to 30 percent of nursing home residents would be more appropriately served in assisted living communities (Clipp, 1995). The magnitude of that estimate suggests that these so-called "inappropriate" placements may have a significant impact on overall health care costs for the frail elderly in this country.

b. Source of Admission

The ALFAA-Coopers & Lybrand study (1993) found that more than one-half of the residents lived in their own homes prior to admission to the assisted living facility (57 percent) while 16 percent came from living with their family, 14 percent came from a retirement community, and 13 percent came from a nursing home.

To better understand how elders are referred to residential care settings, one researcher has recently studied patterns of decision making for seniors' transfers into residential care facilities (Bear, 1993). Using a sample of 86 primary caregivers of elderly residents newly admitted to central Florida residential care settings, this study examined the admission patterns of residents described as unable to stay in their current residence (prior to residential care placement) and their subsequent referral to the residential care facility. The majority (68.5 percent) of seniors were labeled "out-of-place" and 75.6 percent were referred by informal primary caregivers. Physicians labeled 25.6 percent of the seniors out-of-place and referred 15.1 percent of the seniors to the residential care setting. Health professionals were more likely to do the labeling during a hospitalization. The study found that caregivers of this sample of residents differed from a national sample of caregivers; they were more frequently white, younger, and better educated than the national sample.

ALFAA's survey reports somewhat different referral patterns in its Overview of the Assisted Living Industry: 25 percent of the residents in the facilities responding to the survey were referred by family members, while 20 percent were referred by hospitals, 14 percent were referred by physicians, and 14 percent were self-referrals.

c. Admission and Retention Criteria

Some useful background to the discussion of admission criteria for assisted living facilities is provided in a recent national study on board and care homes (Hawes, et al., 1995). The authors do not explicitly describe a set of characteristics or eligibility requirements for board and care residents, except that such residents tend to need temporary, part-time nursing care and some assistance with ADLs. In terms of discharge conventions, 44 percent of licensed board and care homes and 56 percent of unlicensed board and care homes (assisted living facilities would most likely fall under this category) reported that they would discharge a resident who needed nursing care for more than 14 days. The discharge sites listed were hospitals (acute or Veterans Administration) and nursing homes (Hawes et al., 1995, p. 17).

The Kane and Wilson (1993) national study also examined admission and retention policies for the assisted living facilities they studied. All but one of the 63 facilities surveyed would admit an individual who was mildly confused. All 63 facilities would retain a resident who was mildly confused and all had at least one mildly confused resident. In contrast, 45 of the 63 facilities would admit an individual with moderate confusion and 55 of the 63 would retain an individual with moderate confusion. Fifty-three out of the 63 facilities actually had residents with moderate confusion. In addition, only 12 of the 63 facilities would admit individuals using a ventilator and 12 of the 63 would retain a resident on a ventilator. Of those 12 facilities, only three actually had one or more residents on a ventilator. Exhibit 3.3 presents the table on admission and retention policies from the Kane and Wilson study. Although the authors found that a certain number of facilities would admit and/or retain individuals conditionally with selected conditions, these facilities have been omitted from the table.

State regulations increasingly influence who is eligible to become an assisted living resident as well as the length of time that a resident may remain in a particular facility. The recent Guide to Assisted Living and State Policy (Mollica et al., May, 1995) provides some important analysis of admission and discharge regulations. This report indicates that 17 states have admission criteria that admit only those residents who require nursing facility level of care or skilled services (Mollica et al., 1995, ix). However, it seems that resident policies which prohibit anyone needing nursing home level of services from being served are being reexamined. As Mollica et al. argue, "assisted living has been developed as an alternative for people who qualify for placement in a nursing facility in most states" (Mollica et al., p. 45).

| EXHIBIT 3.3: Admission and Retention Policies and Presence of at Least One Current Tenant with Selected Problems in 63 Assisted Living Settings | |||

| Condition or Problem | Will Admit | Will Retain | Current Have Residents with Condition |

| Wheelchair bound | 56 | 57 | 50 |

| Electric Cart | 46 | 46 | 22 |

| Incontinent | 55 | 60 | 56 |

| Chair Bound | 19 | 24 | 28 |

| Help Transfer | 32 | 42 | 32 |

| Help Feed | 28 | 32 | 24 |

| Mildly confused | 62 | 63 | 63 |

| Moderately confused | 45 | 55 | 53 |

| Using catheter/ostomy | 53 | 56 | 31 |

| Using Oxygen | 55 | 49 | 44 |

| Using Ventilator | 12 | 12 | 3 |

| With Behavior Problems | 38 | 46 | 42 |

| (Kane & Wilson, 1993) | |||

Currently, the State of Virginia does not allow bedfast residents to enter assisted living facilities, although those residents who become bedfast after admission to the facility may remain. In addition, the state of Missouri requires that assisted living residents be capable of walking within 45 days of admission (Provider, August, 1993). Regulations prepared for the state of Florida prohibit residents with certain conditions from remaining in assisted living facilities (called extended congregate care in Florida). These conditions include: needing 24-hour nursing supervision, being bedridden for more than two consecutive weeks, dependency in four or more ADLs, or being unable to make simple decisions due to cognitive impairment (Rajecki, 1992).

Mollica et al. also contributed some valuable information on the topic of admission criteria. Their Guide to Assisted Living and State Policy specifically differentiated state licensing rules that specify admissions criteria from the program requirements that establish such criteria. In addition, Mollica et al. explored two important distinctions in the determination of admissions criteria. Their study explains that state licensure rules often establish guidelines regarding who may be served in an assisted living facility regardless of payer source. However, state reimbursement policy may establish specific criteria for residents that will be reimbursed through Medicaid in assisted living.

c. Length of Stay

The average length of stay reported by ALFAA is 2.2 years with a median of 2.0 years. Kane and Wilson's national study of 63 assisted living facilities for AARP found that assisted living residents had an average length of stay of 26 months. The most frequently cited reasons for residents leaving in the Kane and Wilson national study were: 1) the need for greater care; 2) behavioral problems; 3) improvement in functioning; 4) not enough funds; and 5) spouse died/moved. In contrast, other researchers have found a mean length of stay in seven CCRCs to be 7.5 years (Newcomer, Preston, and Roderick, June, 1995). It has also been reported that females average more than six month longer lengths of stay than males in both assisted living and nursing units (Newcomer, Preston, and Roderick, June, 1995).

d. Discharge Criteria

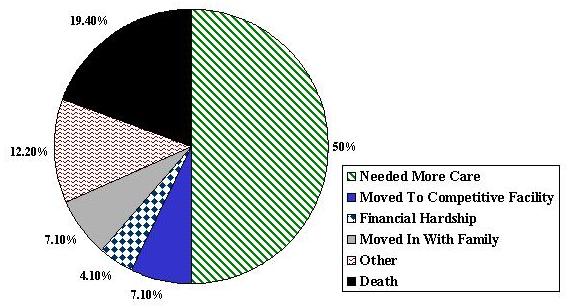

Literature produced in the last six months has contributed to the body of information on discharge patterns among assisted living residents. A report on one 400-resident facility with independent living units, assisted living units, and skilled nursing in the same setting indicates anecdotally that transfers between levels of care are frequent (Young & Hegyvary, 1993). Both the ALFAA study and Kane and Wilson's national study appear to confirm that transfers out of assisted living are frequent. ALFAA reports an annual mean turnover rate of 34 percent and that the greatest number of residents discharged from the assisted living facilities surveyed go to nursing homes (46 percent) with the next greatest numbers of residents discharged due to death (24 percent) or discharged to the hospital (12 percent). The Coopers & Lybrand and ASHA 1994 report, The State of Seniors Housing 1994, supplies recent turnover data to complement that of the Kane and Wilson research. Coopers & Lybrand studied the reasons for turnover and developed a chart based on their results (Exhibit 3.4).

| EXHIBIT 3.4: Reasons for Leaving Assisted Living Facilities |

|

| SOURCE: ASHA-Coopers & Lybrand, 1994. |

Mollica et al. explain that in many states "maximum thresholds" are established, that is, some states specify which types of residents must be discharged. Although the report indicates that these discharge rules are fairly broad, they do allow facilities to determine the types of needs that can be met within their facility through the resident agreement process.

e. Discharge Destinations

In examining resident discharge destinations from assisted living facilities involved in their national study, Kane and Wilson found that, in the previous year, 26 of 59 assisted living facilities reported that 25 percent or more of their residents who moved out went to a nursing home and 11 of 59 reported that 50 percent or more of move-outs went to a nursing home. Twenty out of 59 facilities reported that 25 percent or more of their residents go to the hospital and do not return while 17 of the 59 facilities reported that 25 percent or more went to the hospital and died. Six of the 59 facilities reported that 25 percent or more of residents who moved out went to an independent living setting while two reported that 25 percent or more went to other assisted living facilities. Kane and Wilson point out that "substantial numbers died in the assisted living setting or died after a short hospitalization" and that "depending on one's view of the desirable capacity for assisted living, these figures are encouraging because they suggest many people can remain in the setting until death or shortly before" (Kane & Wilson, 1993, p. 30).

Kane and Wilson (1993) also studied the discharge destinations of 371 Oregon residents who left the 20 facilities since 1990. They found that 66 died in the assisted living facility, 64 were discharged to a nursing home, 49 were discharged to their own home, 48 went to a hospital and died after hospitalization.

C. ARCHITECTURE AS AN IMPORTANT COMPONENT OF THE ASSISTED LIVING PHILOSOPHY

A core tenet of the philosophy of assisted living is that the assisted living setting is important to both the physical and psychological well-being of the frail elderly. Many recent definitions of assisted living employ words like "homelike" to describe the ideal assisted living setting, and some experts argue that caregivers and health professionals should use "the residential environment as the basis for therapeutic intervention" (Regnier, 1994, p. 3).

A growing interest in the role of physical environment and architecture, in particular, as issues in assisted living is demonstrated by a burgeoning literature on the topic. Two recent books on architecture and assisted living (Regnier, 1994; Salmon, 1993) and seven articles (Bauer, 1992; Building Design & Construction, 1994; Dorn, 1993; Geran, 1993; Hoglund, 1992; Progressive Architecture, 1994; Regnier, 1992) explain the importance of architecture.

1. Regnier's Architectural Criteria for Assisted Living and His Influence on the Current Literature on Architectural Criteria

Regnier uses nine criteria to define assisted living facilities. They are: 1) appear residential in character; 2) perceived as small in size; 3) provide residential privacy and completeness (i.e., with a full bathroom and a kitchenette at a minimum); 4) recognize the uniqueness of each resident; 5) foster independence, interdependence, and individuality; 6) focus on health maintenance, physical movement, and mental stimulation; 7) support family involvement; 8) maintain connections with the surrounding community; and 9) serve the frail elderly (Regnier, 1992, 1994).

Technological advances may change assisted living facilities even more in the future. Regnier maintains that "as new forms of robotics and communications technology challenge the concept of institutional control, assisted living will become an even more popular avenue for caring for the frail" (Regnier, 1994, p. 1).

To support Regnier's nine-point analysis, recent non-architectural literature is beginning to define assisted living facilities in terms of several of his criteria. Robert and Rosalie Kane note in their 1995 JAMA article that many states now license facilities with the name "assisted living" only if they feature single-occupancy apartment units with full bathrooms and kitchenettes. In addition, in consideration of Regnier's other criteria of "independence, interdependence, and individuality," many experts are promoting the notion of "aging in place." Closely linked with planning and development around physical structure, "aging in place," as discussed by Ivry and others, requires that the assisted living unit be adaptable in its design so that a resident with increasing ADL needs could be accommodated in that same unit over a period of time.

The AARP has also contributed to the literature regarding the confluence between architecture and the philosophy of assisted living. Citing Regnier's work and consistent with the findings of the ALFAA study and the Kane and Wilson study, a recent AARP policy brief describes the range of design elements found in assisted living facilities. Two unit types are described: the first is a private room with bath, individual temperature controls, and locking doors and the second is a small apartment with a kitchenette. The policy brief also indicates that many assisted living facilities include a laundry, central kitchen, and recreational areas in order to support the services that are included with the residents' rental packages. Resident choice over decor, including the increasingly popular option for residents to supply their own furnishings, is one of many steps toward the goal of creating a home-like environment. Another step is the creation of small sitting rooms around the facility to encourage residents to interact with one another and with guests. In addition, many facilities avoid the use of fluorescent lighting, long corridors, tiling and other design features that are more consistent with the bygone institutional paradigm. While promoting this home-like interior design idea, many assisted living facilities must also provide standard safety features to aid frail residents with mobility problems. Handrails, wide hallways, grab bars, emergency call systems, and other security features are present in many facilities.

2. Autonomy-enhancing Features

Many design features are thought to contribute to residents' independence and autonomy in assisted living facilities. Kane and Wilson (1993) found in their national study that 26 of the 63 facilities exclusively had private units with 24 more having more private than double-occupancy units and four with equal numbers of single- and double-occupancy units. The ALFAA study (1993) does not provide any indication of how many units are single or double occupancy. In Exhibit 3.5, a comparison of some features considered to be autonomy-enhancing from the ALFAA and Kane and Wilson studies are presented.

In their national study, Kane and Wilson (1993) found that residents in 47 out of 63 facilities had the capability to lock their doors. (This issue is not discussed in the ALFAA report.)

| EXHIBIT 3.5: A Comparison of the Percentage of Facilities with Autonomy Enhancing Features from Two Studies -- in Percentage | ||

| Autonomy Enhancing Feature | ALFAA Study | Kane & Wilson Study |

| Bath or Shower in unit | 90% | 95% |

| Refrigerator in unit | 90% | 52% |

| Stove in unit | 76% | 27% |

They also found that residents were not allowed to have stoves in 44 facilities, although they were not allowed to have refrigerators in only 14 facilities. The prohibition against stoves may reflect concerns about fire hazards. The conflict between autonomy-enhancing features of assisted living and state regulatory and licensure stipulations will be discussed in a later chapter.

The 1995 Guide to Assisted Living and State Policy also addressed this issue of autonomy-enhancing features. Mollica et al. argue that "while some contend that apartment style models raise costs and require features that residents may or may not use or that may be harmful (stoves, microwaves), others contend that kitchens or kitchenettes do not add significant costs, can be safe and provide an ambiance that is familiar and encourages autonomy" (Mollica et al., p. iii).

3. Current Architectural Prototypes and Standards