Printer Friendly Version in PDF Format (32 PDF pages)

ABSTRACT

This paper seeks to document the frequency of Medicaid coverage loss among full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries and identify potential causes for coverage loss. For dual eligible beneficiaries, the loss of full-benefit Medicaid coverage is of concern because most of them do not have an alternative source of health insurance for the services covered by full-benefit Medicaid. For providers involved in the care of dual eligible beneficiaries, discontinuity in full-benefit Medicaid coverage may lead to disruption in care and adverse health outcomes.

There is wide variation in the rates of full-benefit Medicaid coverage loss across states, driven in part by state Medicaid eligibility policies. New full duals in 209(b) states, or in states that apply the special income rule were more likely to lose coverage than those in states without such policies, while individuals in states that provide poverty-level coverage had lower risk of losing coverage. Findings suggest that states with relatively more inclusive Medicaid eligibility coverage policies (which may have more streamlined recertification and other procedural requirements) tend to decrease coverage loss than states with relatively more restrictive Medicaid coverage.

High "churning" in dual eligible status is problematic for both individual beneficiaries and providers. For dual eligible beneficiaries, the loss of full-benefit Medicaid coverage is of concern because most of them do not have an alternative source of health insurance for the services covered by full-benefit Medicaid. Without Medicaid support, many of these low-income individuals may have difficulty paying for cost-sharing of Medicare services and may be unable to access services that are not covered by Medicare (such as long-term services and supports). For providers involved in the care of dual eligible beneficiaries, discontinuity in full-benefit Medicaid coverage may lead to financial losses.

This report was prepared under contract #HHSP233201600021I between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy (DALTCP) and the Research Triangle Institute. For additional information about this subject, you can visit the DALTCP home page at http://aspe.hhs.gov/office-disability-aging-and-long-term-care-policy-daltcp or contact the ASPE Project Officer, Jhamirah Howard, at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201; Jhamirah.Howard@hhs.gov.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization. This report was completed and submitted on September 2017.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. BACKGROUND

1.1. Medicaid Coverage Among Full-Benefit Dual Eligible Beneficiaries

1.2. Limited Understanding of Medicaid Coverage Loss among Full-Benefit Dual Eligible Beneficiaries

2. METHODS

2.1. Subject Matter Expert Interviews

2.2. Quantitative Analysis

3. RESULTS

3.1. Reasons for Loss of Medicaid Coverage, According to Subject Matter Experts

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

4.1. Discussion

4.2. Conclusion

5. REFERENCES

APPENDIX A: Additional Tables

LIST OF EXHIBITS

- EXHIBIT 1: Percentage of New Full-Duals with Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status, 2007-2009, by State

- EXHIBIT 2: Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status, 2007-2009, by Beneficiary Characteristics

- EXHIBIT 3: Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status, 2007-2009, by State Medicaid Eligibility Policies

- EXHIBIT 4: Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status

- EXHIBIT 5: Predicting Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status, 2007-2009, Multivariate Survival Analysis Results

LIST OF TABLES

- TABLE A-1: State Medicaid Eligibility Policies for Older People and Individuals with Disabilities, 2009

- TABLE A-2: Variables and Descriptive Statistics of Study Sample

- TABLE A-3: Predicting Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status, 2007-2009, Multivariate Logistic Regression Results

ACRONYMS

The following acronyms are mentioned in this report and/or appendix.

| ACA | Affordable Care Act |

|---|---|

| CMS | Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| DI | Disability Insurance |

| D-SNP | Dual Eligible Special Needs Plan |

| ESRD | End-Stage Renal Disease |

| FFS | Fee-For-Service |

| HCBS | Home and Community-Based Services |

| LCL | Lower Confidence Limit |

| LTSS | Long-Term Services and Supports |

| MACPAC | Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission |

| MedPAC | Medicare Payment Advisory Commission |

| MMLEADS | Medicare-Medicaid Linked Enrollee Analytic Data Source |

| OASI | Old Age and Survivor's Insurance |

| RTI | Research Triangle Institute |

| SSA | U.S. Social Security Administration |

| SSI | Supplemental Security Income |

| UCL | Upper Confidence Limit |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

ES.1. Background

Dual eligible beneficiaries constitute an important subset of the Medicare and Medicaid populations because these individuals are low income and have a high prevalence of chronic conditions and disabilities, substantial care needs, and disproportionately high Medicaid and Medicare expenditures. While stability in Medicare coverage is expected for all those enrolled, Medicaid coverage can be more volatile due to fluctuations in income, eligibility, and renewal requirements. Past research has not specifically considered stability of enrollment among new, full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries following their initial transition to full-dual eligibility, and little is known about loss of Medicaid coverage for dual eligible beneficiaries.

For dual eligible beneficiaries, the loss of full-benefit Medicaid coverage is of concern because most of them do not have an alternative source of health insurance for the services covered by full-benefit Medicaid. For providers involved in the care of dual eligible beneficiaries, discontinuity in full-benefit Medicaid coverage may lead to disruption in care and adverse health outcomes. This policy brief seeks to document the frequency of Medicaid coverage loss among full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries and identify potential causes for coverage loss.

ES.2. Methods

We used both quantitative and qualitative methods to gather information on the loss of Medicaid coverage among full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries and possible causes. We conducted semi-structured, key informant interviews with ten subject matter experts who are knowledgeable about the dual eligible population and state Medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and redetermination procedures. These qualitative interviews were used to provide context for the interpretation of the results from quantitative data analysis.

The quantitative analysis used the national Medicare-Medicaid Linked Enrollee Analytic Data Source for 2006-2010. We focused on new dual eligible beneficiaries with full Medicaid and Medicare benefits. We then identified new, full-duals losing full-benefit dual status in the 12 months following their initial transition to that status, both with any break in coverage and a break in coverage lasting longer than 3 months. We conducted descriptive and multivariate analyses to examine the effects of beneficiary characteristics and state Medicaid eligibility policies on the risk of coverage loss.

ES.3. Qualitative Results

-

Experts interviewed noted that the most common reason for a full-benefit dual eligible beneficiary to lose coverage would be failure to comply with certain administrative requirements, and less common reasons were changes in eligibility due to changes in income, assets, or functional status.

-

Respondents indicated that both a lack of awareness of Medicaid program recertification requirements and the administrative burden of these requirements would contribute to coverage loss. They thought that individuals who were new to Medicaid could be especially vulnerable because of their lack of knowledge of Medicaid processes and procedures.

ES.4. Quantitative Results

-

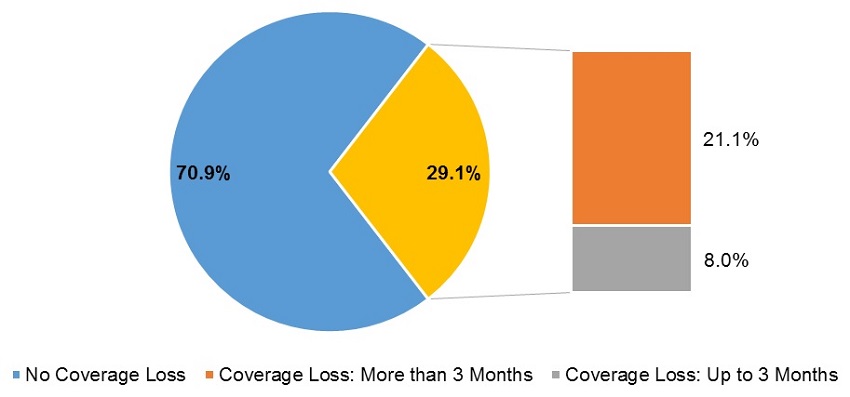

Among 2,580,078 individuals who newly transitioned to full-benefit dual eligible status during 2007-2009 and were followed for 12 months after the transition, 750,243 (or 29.1%) lost coverage for at least 1 month, and 543,659 (or 21.1%) lost coverage for more than 3 months, during these 12 months of follow-up.

-

Compared to beneficiaries who were eligible for Medicaid based on receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) cash benefits, those who were eligible based on medically needy status, poverty-level coverage, Section 1115 Waivers, or other eligibility category had significantly higher risk of losing full-benefit Medicaid coverage.

-

Compared to beneficiaries who were originally eligible for Medicare due to age (turning 65), those who were eligible because of disability or end-stage renal disease had 50% and 65% greater risk of losing coverage, respectively.

-

Individuals who became Medicaid-eligible first before gaining Medicare eligibility had a 37% lower risk of losing coverage compared to those who started with Medicare coverage and transitioned to full-benefit Medicaid eligibility.

-

Individuals in 209(b) states had a 32% higher risk of losing coverage, and those in states that apply the special income rule had 71% higher risk of losing coverage, compared to those in other states. Individuals in states that offer poverty-level coverage had a 38% lower risk of losing coverage. The individual-level risk of coverage loss did not differ significantly in states with the medically needy option and in other states without such an option.

ES.5. Discussion and Conclusion

Contrary to expectations, a substantial number--nearly 30%--of new full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries lose coverage for at least 1 month during the 12 months immediately following their initial transition to full-dual eligible status. This frequency of coverage loss among new, full-benefit dual eligibles is notably higher than reported in previous studies that typically included a cross-section of dual eligibles, most of whom were not new duals. In addition, nearly 30% of those who lost coverage had short coverage breaks for 1-3 months, likely for reasons that are administrative in nature. These findings suggest that new dual eligible beneficiaries may be more unstable, as compared to other, more "established" duals. According to subject matter experts, this coverage instability may be due in part to unfamiliarity with Medicaid policies and eligibility verification procedures.

This analysis also sheds light on how Medicaid eligibility is associated with loss of Medicaid coverage at the individual level. Those who qualified for Medicaid coverage by receipt of SSI-cash benefits were the most stable group and those in the medically needy eligibility category were among the least stable. These findings are consistent with subject matter experts' expectations.

There is wide variation in the rates of full-benefit Medicaid coverage loss across states, driven in part by state Medicaid eligibility policies. New full-duals in 209(b) states, or in states that apply the special income rule were more likely to lose coverage than those in states without such policies, while individuals in states that provide poverty-level coverage had lower risk of losing coverage. Findings suggest that states with relatively more inclusive Medicaid eligibility coverage policies (which may also have less stringent or more streamlined recertification and other procedural requirements) tend to decrease coverage loss than states with relatively more restrictive Medicaid coverage.

High "churning" in dual eligible status is problematic for both individual beneficiaries and providers. For dual eligible beneficiaries, the loss of full-benefit Medicaid coverage is of concern because most of them do not have an alternative source of health insurance for the services covered by full-benefit Medicaid. Without Medicaid support, many of these low income individuals may have difficulty paying for cost-sharing of Medicare services and may be unable to access services that are not covered by Medicare (such as long-term services and supports). For providers involved in the care of dual eligible beneficiaries, discontinuity in full-benefit Medicaid coverage may lead to financial losses.

1. BACKGROUND

More than 11 million people are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid services, and this population continues to grow (CMS, 2016). Dual eligible beneficiaries constitute an important subset of the Medicare and Medicaid populations because these individuals are low income and have a high prevalence of chronic conditions and disabilities, substantial care needs, and disproportionately high Medicaid and Medicare expenditures (Young et al., 2013). Individuals who are dually eligible can receive either partial or full Medicaid benefits depending on state Medicaid eligibility criteria. Partial-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries receive limited Medicaid support for Medicare premiums and sometimes cost-sharing; full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries receive the full range of Medicaid benefits, including coverage of long-term services and supports (LTSS), in addition to assistance with Medicare premiums and cost-sharing (MedPAC & MACPAC, 2017). Generally, full-benefit dual eligibles are expected to have relatively stable Medicaid enrollment due to their low income and high health care and LTSS needs, especially among older people and people with disabilities, whose income and assets are expected to be stable (Ku & Steinmetz, 2013).

Since dual eligible beneficiaries represent a vulnerable population, gaps in insurance coverage can compromise access to care and result in increased costs and decreased quality of care, further increasing an individual's risk for adverse health outcomes (CMS, 2015). A prior study found that a substantial proportion, approximately 30%, of new, full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries identified during 2007-2010 lost full-benefit coverage for at least 1 month in the 12 months following their transition to full-benefit dual status (Feng et al., 2017). Another study found among all dual eligibles, 15.6% lost Medicaid benefits in the 2009-2011 period. Dual eligibles younger than 65 had a higher rate of coverage loss, 21.4%, compared with those age 65 and older (Riley, Zhao, & Tilahun, 2014). Among all Medicaid enrollees in 2010-2011, individuals were enrolled for about 80% of the year (Ku & Steinmetz, 2013). Older people and persons with disabilities are enrolled for a greater portion of the year than other adults. As months of enrollment increased and continuity of Medicaid coverage improved, the average monthly cost of Medicaid coverage decreased (Ku & Steinmetz, 2013).

This policy brief aims to identify potential causes for the loss of Medicaid coverage among full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries. While stability in Medicare coverage is expected because of eligibility due to age and the very low rate of exit from either Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance, Medicaid coverage can be more volatile due to fluctuations in income, eligibility and renewal requirements (Riley et al., 2014). This analysis focuses on full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries, as opposed to partial duals, as they constitute the majority of all dual eligibles and are among the highest cost and most vulnerable enrollees. In addition, the contribution of Medicaid toward health care use and spending is more modest for partial duals than for full-duals. We aim to better understand the relationship between states' Medicaid eligibility and enrollment policies and reasons for loss of Medicaid coverage among full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries. Understanding the factors associated with gaps in dual coverage is the first step toward creating policies to mitigate loss of coverage and improve health outcomes for this population.

1.1. Medicaid Coverage Among Full-Benefit Dual Eligible Beneficiaries

Federal law requires states to provide Medicaid coverage to older people and individuals with disabilities who meet certain income, asset, and functional criteria. A categorization of key state Medicaid eligibility policies for older people and persons with disabilities is detailed in Appendix Table A-1). The most common pathways to Medicaid eligibility for older people and persons with disabilitiesare SSI and the Special Income Limit (Accius, Flowers, & Flinn, 2017).

In 39 states,[1] individuals receiving SSI benefits are eligible to receive Medicaid benefits. Among these SSI states, where receipt of SSI benefits is the same as meeting Medicaid eligibility standards, a further subset, known as "1634 States," automatically enroll individuals receiving SSI in Medicaid and do not require a separate application for Medicaid (SSA, 2014).

States in which receipt of SSI is not sufficient for determining Medicaid eligibility are referred to as "209(b) States" after the section of the Social Security Act that authorizes this policy. The 209(b) states establish standards for Medicaid eligibility that are more restrictive than the SSI criteria with regard to either the level of income or the way that income and medical expenses are counted toward Medicaid eligibility. All 209(b) states are required to allow older people and people with disabilitiesto spend down to the state's income and asset levels. States also have the option of providing coverage to older people and people with disabilities with incomes up to 100% of the federal poverty level (Stone, 2011).

States also have the option of extending Medicaid benefits to individuals through the Special Income Rule. Individuals receiving Medicaid benefits through the Special Income Rule must require an institutional level of care for at least 30 consecutive days, meet a designated resource threshold and have income below a specified level. States that choose to use the Special Income Rule but do not allow the medically needy option must allow individuals to place excess income into a Miller Trust. Miller Trusts allow individuals with incomes above the state-specified limit for the Special Income Rule to assign excess income to the Miller Trust, allowing them to qualify for Medicaid through the Special Income Rule.

Additionally, states may provide coverage to individuals if they are "medically needy." Individuals are considered medically needy if their income minus out-of-pocket medical expenses places them below a state-established income and asset level during a specified period, known as the budget period. Both the amount of medical expenses and budget period are state specific.

Individuals may also receive benefits through Section 1115 research and demonstration waivers. States must apply to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to waive certain provisions of the Medicaid statute in order to demonstrate innovative approaches to increase access to Medicaid for individuals, provided they do so in a way that is budget neutral to the Federal Government. In applying for Section 1115 Waivers, the state must demonstrate that the demonstration will increase coverage and access to Medicaid, improve health outcomes, and increase the quality of care for the low income population served by Medicaid. Most often this is accomplished through delivery system reform. Eligibility and benefits received under Section 1115 Waivers vary by state (CMS, 2017).

1.2. Limited Understanding of Medicaid Coverage Loss among Full-Benefit Dual Eligible Beneficiaries

Past research has not specifically considered stability of enrollment among new, full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries following their initial transition to full-dual eligibility. However, there are a few studies examining the loss of Medicaid coverage for full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries. A 2014 study found that among a 5% sample of all full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries nationally, 15.6% lost Medicaid benefits in the 36-month study period, January 2009-December 2011 (Riley et al, 2014). Among those losing benefits, almost one-third (28.8%) lost benefits for only 1-3 months and just over one-half (51.3%) eventually regained benefits. The authors also find that a higher probability of maintaining Medicaid coverage is associated with higher Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) expenses (among those not enrolled in Medicaid prepaid plans) and with enrollment in a Dual Eligible Special Needs Plan (D-SNP). Those enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans were more likely to lose Medicaid coverage.

A recent study considered the continuity of Medicaid coverage through the creation of Medicaid enrollment "continuity ratio," which calculates the length of Medicaid enrollment in a year by dividing the average monthly number of Medicaid enrollees during a fiscal year by the number of unduplicated individuals enrolled in Medicaid at any time during the year (Ku & Steinmetz, 2013). In the 2010-2011 period, the overall continuity ratio was 81%; the ratio was 86% in the aged population, 90% in the blind/disabled population, 83% among children, and 72% among nondisabled adults.

A study completed by the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2006 examined the stability of Medicaid coverage (regardless of partial-benefit or full-benefit status) among those who had Medicare coverage in the 1997-2000 time frame. Over the 4 years examined, among all Medicare beneficiaries in the sample, 20.6% were dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare, 12.5% had continuous Medicaid enrollment and 8.1% had noncontinuous Medicaid enrollment (Stuart & Singhal, 2006). Those with continuous Medicaid enrollment do not differ substantially in age from those with noncontinuous enrollment.

2. METHODS

We used a combination of methods to gather information on the loss of Medicaid coverage among full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries and possible causes, including interviews with subject matter experts and quantitative data analysis. The information from the subject matter expert interviews was used to provide context for the interpretation of the results from quantitative data analysis.

2.1. Subject Matter Expert Interviews

We conducted semi-structured, key informant interviews with ten subject matter experts who are knowledgeable about the dual eligible population and state Medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and redetermination procedures. Seven of these interviews were with national experts and three were with state Medicaid officials. These interviews occurred from May-June 2017, and each lasted about 45 minutes. The goal of these interviews was to identify Medicaid policies regarding eligibility and enrollment procedures that are possibly related to the loss of full Medicaid benefits among dual eligible beneficiaries. Interviews were conducted according to standard qualitative data collection and evaluation practice, guaranteeing respondent anonymity and confidentiality.

2.2. Quantitative Analysis

2.2.1. Data Source

We used the national Medicare-Medicaid Linked Enrollee Analytic Data Source (MMLEADS) for 2006-2010, the most recent years of this data available at the time of our research. MMLEADS contains data on demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, date of birth, date of death), program eligibility (Medicare-Medicaid coverage initial start date, original reason for Medicare eligibility and current reason for Medicare-Medicaid eligibility, dual status indicator, FFS vs. managed care enrollment), utilization, and spending for all Medicare-Medicaid enrollees (Buccaneer, 2015). Monthly data for most of these variables (e.g., flags for dual status, Medicaid Analytic eXtract uniform eligibility codes, Medicare-Medicaid service utilization and spending) are available in MMLEADS.

2.2.2. Study Population: New, Full-Benefit Dual Eligible Beneficiaries

In this study, we focused on new dual eligible beneficiaries with full Medicaid and Medicare benefits. Full-benefit dual eligibles constitute the majority of all dual eligible beneficiaries. New, full-benefit dual eligibles were defined as individuals who experienced their initial transition to full-benefit dual status at some point from January 2007 through December 2010, but had never been a full-benefit dual in calendar year 2006. This approach allows a look-back period of at least 1 year for every person prior to their initial transition to full-benefit dual status.

Full-dual status was identified using the monthly dual status code with values of either 02 (Qualified Medicare Beneficiaries plus full Medicaid), 04 (Specified Low Income Medicare Beneficiaries plus full Medicaid), or 08 (other full-benefit duals). The original data source for this code is the Medicare Modernization Act State File (Buccaneer, 2015). The first month and year in which an individual was identified as a full-dual was considered their initial point of transition to full-dual status. Using these criteria, we identified a total of 3,881,656 new full-dual eligibles during 2007-2010. For the analysis presented in this brief, we used a subset of 2,580,092 new full-dual eligibles who survived for at least 12 months after their initial transition to full-dual status and had the monthly dual status code available for all those months. In effect, this limited the analysis to those whose initial transition to full-dual eligibility occurred at some point during January 2007-December 2009. This approach allowed us to track all individuals for 12 months after their initial transition to full-dual status, ensuring a comparable follow-up period for assessing the risk of coverage loss.[2]

2.2.3. Measuring Coverage Loss

Among the 2,580,092 new, full-duals identified above who transitioned during 2007-2009, we created two measures of loss of full-benefit dual eligible status in the 12 months following their initial transition to that status. In the first measure, we identified individuals who did not maintain full-benefit dual status for all the 12 months following this transition--in other words, those who lost full-dual coverage for at least 1 month. In the second measure of coverage loss, we identified beneficiaries who had a break in full-dual coverage for more than 3 months out of the 12-month follow-up period (the break may or may not be for consecutive months). Individuals identified by the second measure are a subset of those identified by the first measure. Loss of coverage for 3 or fewer months is likely due to an administrative issue, rather than a change in eligibility, whereas the second measure identifies people for whom the loss of coverage is longer lasting and, therefore, perhaps more consequential to the individual. We focus mainly on the first measure but also present descriptive results for the second measure for comparison purposes.

This analysis measures the loss of full-benefit dual eligible status. Specifically, beneficiaries who lost full Medicaid benefits, either completely or by moving to partial Medicaid benefits, or who lost Medicare benefits would be considered to have lost full-benefit dual eligible status. However, as noted earlier, we expect that very few Medicare beneficiaries would lose Medicare coverage. Thus, in this analysis, while we refer to loss of full-benefit Medicaid eligibility, we recognize the possibility that loss of full-benefit dual eligible status could also result from loss of Medicare coverage.

2.2.4. Statistical Analysis

We first conducted descriptive data analysis to examine the associations of loss of full-benefit dual coverage with beneficiary characteristics: age (at time of transition to full-dual status), sex, race/ethnicity, original reason for Medicare eligibility, reason for Medicaid eligibility (at time of transition to full-dual status), temporal pathway to full-benefit dual eligible status (Medicare-to-Medicaid, Medicaid-to-Medicare, or simultaneous transition to eligibility for both programs), and with selected state Medicaid policies. Additional details regarding these variables and the study population are provided in Appendix Table A-2.

We then examined the independent effects of the above individual-level and state-level policy variables on predicting the likelihood of losing full-benefit Medicaid coverage, using multivariate analysis. We used two different regression modeling techniques. Our main results are based on "time-to-event," or "survival" analysis. This technique compares individuals on their time to coverage loss and measures the effect of each of the variables on the risk of coverage loss, using a Cox proportional-hazards model, with the outcome of any loss of coverage (including 3 or fewer months). Individuals who did not lose coverage over the 12-month follow-up were considered censored as of the end of the 12 months. The model adjusted the standard errors for the clustering of observations within states.

Additionally, as a sensitivity analysis we viewed the loss of full-benefit Medicaid coverage over the course of the 12-month follow-up period as a dichotomous (yes/no) variable, and we performed logistic regression to obtain the independent effect of each of the individual-level and policy-level variables on the probability of coverage loss. The outcome again was any loss of coverage (including 3 or fewer months). To account for the clustering of observations within states, we used state random effects. We expected these two techniques to provide similar results. We present the survival analysis results in the main body of this brief and the logistic model results in the appendix.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Reasons for Loss of Medicaid Coverage, According to Subject Matter Experts

To receive Medicaid benefits, generally an individual must apply to the program in the state in which they reside, and be certified as eligible at least annually, depending on state-specific criteria. Changes in income, assets, or medical need may result in an individual losing Medicaid benefits. Individuals may also lose Medicaid coverage if they fail to meet the administrative requirements, such as attending an in-person interview to renew their Medicaid benefits or providing documentation of income and assets to demonstrate their continued eligibility. Specific policies and renewal processes vary by state.

In general, experts we interviewed expected that the full-dual population would have relatively stable income and assets over time and were likely to sustain Medicaid coverage. However, they noted several reasons that a full-benefit dual eligible beneficiary might lose coverage. They thought the most common reason would be failure to comply with certain administrative requirements; less common reasons were changes in eligibility due to changes in income, functional status, or assets.

Respondents believed that full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries would be most likely to lose coverage because of a failure to complete the Medicaid eligibility renewal process. Medicaid eligibility recertification is required at least annually, but this varies by state and eligibility group. Specific administrative issues that may lead to a loss of Medicaid coverage include a state's Medicaid renewal period (the period of time in which an individual must provide proof to the state of their continued eligibility for Medicaid), recertification procedures and requirements, and method of income and asset verification. State Medicaid officials participating in the study noted that in their respective states, beneficiaries were provided with two mailed notices prior to renewal and could respond by mail, online, telephone, or fax. However, recertification procedures vary across states, ranging from passive renewals where prepopulated forms are provided and beneficiaries need to respond only if there has been a change, to requiring in-person applications. Furthermore, some states allow a grace period if an individual fails to recertify using the correct documents or in a timely manner, while others do not. Additionally, some states verify income by sharing information across state agencies, electronic or otherwise, or allow individuals to self-report, while other states require individuals to obtain and provide documentation. Lastly, the verification of assets varies across states.

Respondents indicated that both a lack of awareness of Medicaid program recertification requirements and the administrative burden of these requirements could contribute to individuals losing coverage. Respondents thought that individuals who were new to Medicaid could be especially at risk because of their lack of knowledge of Medicaid processes and procedures. Lack of awareness of annual renewal processes, for example what documents are required and how current those documents need to be, can lead to a denial of coverage. Experts also indicated that they would expect the managed care population, especially D-SNP enrollees, individuals enrolled in state demonstrations under the Financial Alignment Initiative, and those in nursing facilities, to have higher rates of stability in full-dual status because these providers and plans are financially motivated to keep individuals enrolled and may provide aid with recertification. In addition, respondents felt that new Medicaid enrollees might not understand or recall that new information, such as change of address, must be reported. This could leave new, full-duals vulnerable to losing coverage because the state can no longer find them. This is an especially formidable barrier for transient populations who lack access to affordable housing and personal telephone or Internet connections.

Instability of full-dual status may vary by Medicaid eligibility category. Experts expected the greatest amount of instability to be among those eligible for Medicaid through the medically needy/spenddown pathway because of variation in medical and LTSS expenses.

Beneficiaries eligible for Medicaid because of SSI benefits were expected to have relatively less instability; however, respondents noted they expected differences between three types of states. In 1634 States, where individuals are automatically enrolled in Medicaid when they receive SSI benefits, it was hypothesized that SSI beneficiaries in these states would be the most stable. Among SSI states where individuals must separately apply to Medicaid and submit paperwork for recertification each year despite receipt of SSI benefits, more volatility in coverage was expected. In 209(b) states, SSI beneficiaries must also apply for Medicaid separately, and as noted above, these states may have more restrictive criteria for Medicaid eligibility than they have for SSI; therefore, higher volatility in coverage was expected for these states.

Individuals eligible for Medicaid because of the Special Income Rule were expected to be relatively stable. However, experts noted that individuals could lose eligibility by being discharged from a nursing home or because of a slight increase in income (if they did not have a Miller Trust).

Respondents also noted that LTSS providers have the financial incentive to help their beneficiaries remain enrolled using authorized representatives, which may include social workers. The same was thought for those eligible for Medicaid via Section 1115 Waivers or receiving LTSS in the community; these individuals likely receive support from case managers through the re-enrollment process.

Additional reasons proposed for why full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries might lose Medicaid eligibility included having presumptive eligibility taken away, if it was originally, incorrectly granted; experiencing changes in eligibility due to income, which could result, for example, from a spouse passing away, resulting in higher SSI payments and life insurance payments for the widowed spouse; and moving from one state to another may result in disenrollment because states have differing eligibility pathways.

Respondents also noted that beneficiaries may choose to opt out of receiving full Medicaid benefits. Experts felt that beneficiaries might choose this option if they were at risk for losing their provider network if their providers did not participate in Medicaid (because they were enrolled in an Medicare Advantage plan and that plan did not also have a Medicaid managed care plan) or upon learning of the estate recovery requirements after enrolling in full-benefit Medicaid. Federal law requires states to recover Medicaid expenses from an individual's estate. States are required to recover the cost of LTSS, but they may also recover additional Medicaid expenses (Administration on Aging, 2017). Some experts also suggested that for individuals who may not use many Medicaid benefits, the hassle of renewal may not be worth the additional benefit; however, others felt that this was unlikely.

When asked specifically about full-benefit duals becoming partial-benefit duals, experts noted that the most prevalent reason for switching from full-dual to partial-dual status would be an increase in income or assets, as the asset requirements for full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries is generally more stringent than for partial-benefit duals.

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

Overall, among individuals who became dually eligible for full Medicare and Medicaid benefits for the first time during 2007-2009 and were followed for 12 months after the transition, 750,243 out of 2,580,078 (29.1%) lost coverage for at least 1 month during a 12-month follow-up (Exhibit 1). There was substantial variation across states in the likelihood of losing full-benefit Medicaid coverage.[3] Rates of coverage loss ranged from 15.3% in New Jersey, 16.9% in Colorado, and 17.2% in Oklahoma, to 43.8% in Ohio, 52.1% in Indiana, and 67.9% in Georgia. The average rate of coverage loss across all the states was 28.9%, and the median was 26%.

| EXHIBIT 1. Percentage of New Full-Duals with Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status, 2007-2009, by State | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Beneficiaries with 12 Months of Follow-up |

No Loss of Coverage | Loss of Coverage: At Least 1 Month |

Loss of Coverage: More than 3 Months |

|||

| N | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| AK | 4,364 | 3,557 | 81.5 | 807 | 18.5 | 403 | 9.2 |

| AL | 28,151 | 20,832 | 74.0 | 7,319 | 26.0 | 3,816 | 13.6 |

| AR | 28,428 | 20,620 | 72.5 | 7,808 | 27.5 | 6,207 | 21.8 |

| AZ | 48,760 | 35,998 | 73.8 | 12,762 | 26.2 | 9,390 | 19.3 |

| CA | 340,118 | 266,614 | 78.4 | 73,504 | 21.6 | 45,760 | 13.5 |

| CO | 24,348 | 20,228 | 83.1 | 4,120 | 16.9 | 2,925 | 12.0 |

| CT | 31,606 | 23,576 | 74.6 | 8,030 | 25.4 | 5,758 | 18.2 |

| DC | 7,524 | 5,467 | 72.7 | 2,057 | 27.3 | 1,133 | 15.1 |

| DE | 5,170 | 3,354 | 64.9 | 1,816 | 35.1 | 1,526 | 29.5 |

| FL | 153,194 | 93,783 | 61.2 | 59,411 | 38.8 | 50,386 | 32.9 |

| GA | 75,228 | 24,139 | 32.1 | 51,089 | 67.9 | 41,544 | 55.2 |

| HI | 10,475 | 7,935 | 75.8 | 2,540 | 24.2 | 1,410 | 13.5 |

| IA | 24,718 | 20,267 | 82.0 | 4,451 | 18.0 | 2,998 | 12.1 |

| ID | 8,789 | 6,746 | 76.8 | 2,043 | 23.2 | 1,122 | 12.8 |

| IL | 122,262 | 83,215 | 68.1 | 39,047 | 31.9 | 29,527 | 24.2 |

| IN | 59,637 | 28,586 | 47.9 | 31,051 | 52.1 | 24,469 | 41.0 |

| KS | 19,660 | 12,546 | 63.8 | 7,114 | 36.2 | 4,841 | 24.6 |

| KY | 36,918 | 24,946 | 67.6 | 11,972 | 32.4 | 9,415 | 25.5 |

| LA | 39,961 | 30,414 | 76.1 | 9,547 | 23.9 | 8,050 | 20.1 |

| MA | 86,585 | 68,506 | 79.1 | 18,079 | 20.9 | 12,627 | 14.6 |

| MD | 30,117 | 22,412 | 74.4 | 7,705 | 25.6 | 5,498 | 18.3 |

| ME | 19,575 | 14,645 | 74.8 | 4,930 | 25.2 | 3,511 | 17.9 |

| MI | 94,693 | 67,523 | 71.3 | 27,170 | 28.7 | 19,962 | 21.1 |

| MN | 43,298 | 32,780 | 75.7 | 10,518 | 24.3 | 7,224 | 16.7 |

| MO | 57,200 | 36,509 | 63.8 | 20,691 | 36.2 | 16,188 | 28.3 |

| MS | 29,853 | 18,950 | 63.5 | 10,903 | 36.5 | 8,672 | 29.0 |

| MT | 6,937 | 4,067 | 58.6 | 2,870 | 41.4 | 2,318 | 33.4 |

| NC | 83,996 | 58,705 | 69.9 | 25,291 | 30.1 | 19,070 | 22.7 |

| ND | 5,017 | 3,104 | 61.9 | 1,913 | 38.1 | 1,517 | 30.2 |

| NE | 12,615 | 9,156 | 72.6 | 3,459 | 27.4 | 1,934 | 15.3 |

| NH | 10,059 | 5,750 | 57.2 | 4,309 | 42.8 | 3,318 | 33.0 |

| NJ | 60,517 | 51,261 | 84.7 | 9,256 | 15.3 | 5,553 | 9.2 |

| NM | 13,161 | 9,807 | 74.5 | 3,354 | 25.5 | 2,707 | 20.6 |

| NV | 8,681 | 5,543 | 63.9 | 3,138 | 36.1 | 2,002 | 23.1 |

| NY | 215,228 | 168,658 | 78.4 | 46,570 | 21.6 | 28,950 | 13.5 |

| OH | 118,619 | 66,664 | 56.2 | 51,955 | 43.8 | 42,494 | 35.8 |

| OK | 35,577 | 29,450 | 82.8 | 6,127 | 17.2 | 3,785 | 10.6 |

| OR | 23,625 | 18,081 | 76.5 | 5,544 | 23.5 | 4,058 | 17.2 |

| PA | 133,647 | 105,186 | 78.7 | 28,461 | 21.3 | 21,023 | 15.7 |

| RI | 11,144 | 8,849 | 79.4 | 2,295 | 20.6 | 1,721 | 15.4 |

| SC | 39,207 | 31,972 | 81.5 | 7,235 | 18.5 | 5,266 | 13.4 |

| SD | 4,787 | 3,915 | 81.8 | 872 | 18.2 | 643 | 13.4 |

| TN | 53,429 | 43,366 | 81.2 | 10,063 | 18.8 | 6,982 | 13.1 |

| TX | 125,992 | 84,271 | 66.9 | 41,721 | 33.1 | 22,914 | 18.2 |

| UT | 11,746 | 7,125 | 60.7 | 4,621 | 39.3 | 3,359 | 28.6 |

| VA | 43,608 | 33,242 | 76.2 | 10,366 | 23.8 | 7,661 | 17.6 |

| VT | 7,484 | 5,742 | 76.7 | 1,742 | 23.3 | 1,228 | 16.4 |

| WA | 52,804 | 34,827 | 66.0 | 17,977 | 34.0 | 13,922 | 26.4 |

| WI | 48,934 | 32,096 | 65.6 | 16,838 | 34.4 | 10,632 | 21.7 |

| WV | 19,914 | 12,614 | 63.3 | 7,300 | 36.7 | 5,883 | 29.5 |

| WY | 2,718 | 2,236 | 82.3 | 482 | 17.7 | 357 | 13.1 |

| Total | 2,580,078 | 1,829,835 | 70.9 | 750,243 | 29.1 | 543,659 | 21.1 |

| SOURCE: RTI Analysis of MMLEADS Data. | |||||||

The percentage of new full-dual beneficiaries losing full-benefit Medicaid coverage varied substantially by the individual's Medicaid eligibility pathway to full-dual eligibility and by original reason for Medicare eligibility (Exhibit 2). Individuals who were eligible for Medicaid based on receiving SSI-cash benefits were the least likely to lose coverage (19.3%), while those who were eligible based on a Section 1115 Waiver, which was the smallest eligibility group, were the most likely to lose coverage (55.9%). Beneficiaries who were Medicaid-eligible because of medically needy status also had a high likelihood (39.2%) of losing coverage. Those who were Medicare eligible based on Old Age and Survivor's Insurance (OASI) were less likely to lose Medicaid coverage than those who were eligible based on disability insurance (22.1% vs. 35.6%) or end-stage renal disease status (ESRD) (40.2%). Also important was the temporal pathway to dual eligibility. Those who first attained Medicaid eligibility followed by Medicare eligibility were less likely to lose coverage than those who followed the reverse order (21.7% vs. 32.3%).

| EXHIBIT 2. Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status, 2007-2009, by Beneficiary Characteristics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total | No Loss of Coverage | Loss of Coverage: At Least 1 Month |

Loss of Coverage: More than 3 Months |

|||

| N | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Age | |||||||

| <65 | 1,178,424 | 758,186 | 64.3 | 420,238 | 35.7 | 318,368 | 27.0 |

| >65 | 1,401,668 | 1,071,653 | 76.5 | 330,015 | 23.5 | 225,295 | 16.1 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 1,540,324 | 1,131,472 | 73.5 | 408,852 | 26.5 | 291,384 | 18.9 |

| Male | 1,039,739 | 698,366 | 67.2 | 341,373 | 32.8 | 252,251 | 24.3 |

| Race | |||||||

| White, nonHispanic | 1,530,691 | 1,071,997 | 70.0 | 458,694 | 30.0 | 340,382 | 22.2 |

| African American | 494,616 | 337,400 | 68.2 | 157,216 | 31.8 | 115,887 | 23.4 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 153,825 | 124,768 | 81.1 | 29,057 | 18.9 | 17,566 | 11.4 |

| Hispanic | 362,857 | 269,583 | 74.3 | 93,274 | 25.7 | 61,019 | 16.8 |

| American Indian/ Alaskan Native | 23,581 | 17,323 | 73.5 | 6,258 | 26.5 | 4,348 | 18.4 |

| Medicaid Eligibility | |||||||

| SSI | 877,279 | 707,777 | 80.7 | 169,502 | 19.3 | 113,039 | 12.9 |

| Medically needy | 459,828 | 279,625 | 60.8 | 180,203 | 39.2 | 136,698 | 29.7 |

| Poverty | 433,852 | 279,081 | 64.3 | 154,771 | 35.7 | 114,920 | 26.5 |

| Othera | 691,868 | 503,738 | 72.8 | 188,130 | 27.2 | 132,866 | 19.2 |

| Section 1115 Waiver | 63,141 | 27,827 | 44.1 | 35,314 | 55.9 | 29,090 | 46.1 |

| Medicare Eligibility | |||||||

| OASI | 1,270,410 | 989,426 | 77.9 | 280,984 | 22.1 | 187,299 | 14.7 |

| DI | 1,255,442 | 807,958 | 64.4 | 447,484 | 35.6 | 340,078 | 27.1 |

| ESRD | 54,240 | 32,455 | 59.8 | 21,785 | 40.2 | 16,286 | 30.0 |

| Temporal Pathway | |||||||

| Medicare-to-Medicaid | 1,702,880 | 1,153,168 | 67.7 | 549,712 | 32.3 | 399,636 | 23.5 |

| Medicaid-to-Medicare | 730,608 | 572,404 | 78.3 | 158,204 | 21.7 | 115,723 | 15.8 |

| Simultaneous | 127,647 | 91,430 | 71.6 | 36,217 | 28.4 | 24,375 | 19.1 |

| SOURCE: RTI analysis of MMLEADS data. NOTE:

|

|||||||

Demographic factors also appear to play a role in the likelihood of losing Medicaid coverage. Females (26.5%) and beneficiaries aged 65 and older at the time of initial transition to full-dual status (23.5%) were less likely to lose coverage than males (32.8%) and those younger than age 65 (35.7%), respectively. Among racial and ethnic groups, Asians (18.9%) were the least likely to lose coverage, and African Americans (31.8%) were the most likely to lose coverage.

In addition to these individual-level factors, state-level Medicaid coverage policies appear to play an important role in influencing whether individuals lose Medicaid coverage (Exhibit 3). Beneficiaries in states that offer poverty-level coverage had lower rates of coverage loss than beneficiaries in states that do not (26.0% vs. 33.0%). Similarly, beneficiaries in states that provide medically needy coverage had lower rates of coverage loss than beneficiaries in other states that do not (28.0% vs. 32.1%). In contrast, beneficiaries residing in 209(b) states (34.7%) or states that employ the Special Income Rule (29.6%) had higher rates of coverage loss compared to beneficiaries in states that do not allow such policies (27.6% and 26.7%, respectively).

| EXHIBIT 3. Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status, 2007-2009, by State Medicaid Eligibility Policies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Policy | Total | No Loss of Coverage | Loss of Coverage: At Least 1 Month |

Loss of Coverage: More than 3 Months |

|||

| N | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Poverty Coverage | |||||||

| Yes | 1,451,653 | 1,074,283 | 74.0 | 377,370 | 26.0 | 273,925 | 18.9 |

| No | 1,128,425 | 755,552 | 67.0 | 372,873 | 33.0 | 269,734 | 23.9 |

| 209(b) State | |||||||

| Yes | 537,358 | 350,811 | 65.3 | 186,547 | 34.7 | 143,351 | 26.7 |

| No | 2,042,720 | 1,479,024 | 72.4 | 563,696 | 27.6 | 400,308 | 19.6 |

| Medically Needy Coverage | |||||||

| Yes | 1,888,010 | 1,359,770 | 72.0 | 528,240 | 28.0 | 383,940 | 20.3 |

| No | 692,068 | 470,065 | 67.9 | 222,003 | 32.1 | 159,719 | 23.1 |

| Special Income Rule | |||||||

| Yes | 2,123,548 | 1,494,995 | 70.4 | 628,553 | 29.6 | 458,933 | 21.6 |

| No | 456,530 | 334,840 | 73.3 | 121,690 | 26.7 | 84,726 | 18.6 |

| Miller Trust | |||||||

| Yes | 953,354 | 617,311 | 64.8 | 336,043 | 35.2 | 254,081 | 26.7 |

| No | 1,626,724 | 1,212,524 | 74.5 | 414,200 | 25.5 | 289,578 | 17.8 |

| SOURCE: RTI Analysis of MMLEADS Data. | |||||||

The results reported above are based on any loss of full-benefit Medicaid coverage for at least 1 month during the 12-month follow-up period. When examining the rates of coverage loss lasting longer than 3 months (whether consecutive or not), the rates of coverage loss decrease, although they remain substantial: While 29.1% of new full-duals ever experienced any loss of coverage during 12 months of follow-up, only 21.1% lost coverage for more than 3 months (Exhibit 4). The relationships of the coverage loss rates for more than 3 months with the individual and policy characteristics follow a similar pattern to those observed for the rates of any coverage loss.

| EXHIBIT 4. Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status |

|---|

|

These descriptive, bivariate relationships are confirmed with multivariate regression results. Presented in Exhibit 5 and summarized below are results from the multivariate survival model predicting the time to loss of full-benefit Medicaid coverage since the initial transition to full-dual status. Hazard ratios are reported, which describe the relative risk of losing full-benefit Medicaid coverage. These results are consistent with those obtained from the logistic regression model (included in Appendix Table A-3).

| EXHIBIT 5. Predicting Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status, 2007-2009, Multivariate Survival Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | p-value | 95% Confidence Level | ||

| Individual Level Characteristics | ||||

| Medicaid Eligibility | ||||

| Low Income SSI-Cash (reference) | ||||

| Medically Needy | 3.18 | <0.0001 | 2.66 | 3.80 |

| Low Income Poverty | 2.52 | <0.0001 | 1.79 | 3.54 |

| Othera | 1.34 | 0.0122 | 1.07 | 1.68 |

| Section 1115 Waiver | 3.89 | <0.0001 | 2.79 | 5.42 |

| Temporal Pathway | ||||

| Medicare-to-Medicaid (reference) | ||||

| Medicaid-to-Medicare | 0.63 | <0.0001 | 0.56 | 0.72 |

| Simultaneous | 1.08 | 0.4843 | 0.87 | 1.35 |

| Original Reason for Medicare Eligibility | ||||

| OASI (reference) | ||||

| DI | 1.50 | <0.0001 | 1.33 | 1.70 |

| ESRD | 1.65 | <0.0001 | 1.40 | 1.94 |

| Age | ||||

| 65+ (reference) | ||||

| <65 | 1.32 | 0.0039 | 1.09 | 1.60 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female (reference) | ||||

| Male | 1.17 | <0.0001 | 1.14 | 1.20 |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||||

| White, nonHispanic (reference) | ||||

| Black | 1.10 | 0.1488 | 0.97 | 1.26 |

| Hispanic | 1.00 | 0.9610 | 0.90 | 1.10 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.79 | 0.0003 | 0.70 | 0.90 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.95 | 0.0554 | 0.90 | 1.00 |

| State Policies | ||||

| 209(b) State | 1.32 | 0.0287 | 1.03 | 1.70 |

| Poverty Coverage | 0.62 | 0.0315 | 0.40 | 0.96 |

| Medically Needy | 0.92 | 0.6531 | 0.64 | 1.33 |

| Special Income Rule | 1.71 | 0.0155 | 1.11 | 2.65 |

| SOURCE: RTI analysis of MMLEADS data. NOTE: N=2,511,737.

|

||||

Compared to beneficiaries who were eligible for Medicaid based on receiving SSI-cash benefits, those who were eligible based on medically needy status, poverty-level coverage, other eligibility category, or Section 1115 Waivers had significantly (p<0.01) higher risk of losing full-benefit Medicaid coverage. Such risk appears to be the highest for beneficiaries who were eligible based on Section 1115 Waivers or medically needy status, with hazard ratios indicating over three times the risk of losing coverage for those eligible for Medicaid based on receiving SSI-cash benefits. Compared to beneficiaries who were originally eligible for Medicare based on OASI, those who were eligible based on disability insurance or ESRD had 50% and 65% greater risk of losing coverage, respectively (p<0.01). Individuals who became Medicaid-eligible first before gaining Medicare eligibility had a 37% lower risk of losing coverage compared to those who started with Medicare coverage and transitioned to full-benefit Medicaid eligibility (p<0.01). Multivariate results also confirmed the demographic patterns involving gender, race, and age that were noted in the descriptive results above, although many of the differences between racial and ethnic categories were not statistically significant.

Individuals in 209(b) states had a 32% higher risk of losing coverage, and those in states that apply the Special Income Rule had 71% higher risk of losing coverage, compared to those in other states (p<0.05). Beneficiaries in states that offer poverty-level coverage had a 38% lower risk of losing coverage (p<0.05). The individual-level risk of losing full-benefit Medicaid coverage did not differ significantly among states that had the medically needy policy and in other states without such policy.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

4.1. Discussion

Contrary to expectations, a substantial number--nearly 30%--of new full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries lose coverage for at least 1 month during the 12 months immediately following their initial transition to full-dual eligible status. This frequency of coverage loss is notably higher than reported in several previous studies (Ku et al., 2009; Ku & Steinmetz, 2013; Riley et al., 2014). This discrepancy may be attributable to differences in both the populations studied and measures of coverage loss used. The population of interest in this analysis included individuals who newly became dually eligible beneficiaries, while other studies included a cross-section of dual eligibles, most of whom were not new duals. Eligibility for new duals may be more unstable, especially in the initial months following their transition to dual eligible status, as compared to other, more "established" dual eligibles. In addition, this analysis considered moving from full-benefit to partial-benefit Medicaid coverage to be coverage loss, while in other studies this distinction was rarely made.

Our analysis indicates wide variation in the rates of full-benefit Medicaid coverage loss across states, and this variation seems to be driven in part by state-specific Medicaid eligibility policies. In particular, we found that new full-duals residing in 209(b) states, which tend to have more restrictive eligibility criteria, or in states that apply the Special Income Rule, were more likely to lose full-benefit Medicaid coverage than those in other states without such policies. On the other hand, individuals in states that provide poverty-level coverage or the medically needy option had lower risk of losing coverage. These findings seem to suggest that states with relatively more inclusive Medicaid eligibility coverage policies (which may also have less stringent or more streamlined recertification and other procedural requirements) tend to decrease coverage loss than states with relatively more restrictive Medicaid coverage.

Findings from this analysis also shed light on important individual characteristics associated with loss of full-benefit Medicaid coverage. Particularly, new full-duals who qualified for Medicaid coverage by receipt of SSI had the highest stability in maintaining full-dual eligibility, or lowest risk of experiencing coverage loss in the 12-month period following their initial transition to full-dual status. This may be because some individuals reside in 1634 States, which automatically enroll individuals in Medicaid when they receive SSI benefits. Therefore, these individuals may re-enroll in SSI and not consciously re-enroll in Medicaid, whereas individuals eligible for Medicaid through other pathways need to consciously re-enroll in Medicaid. Individuals who followed any other, nonSSI-cash Medicaid eligibility pathway, such as Medically Needy, Low Income Poverty, and Section 1115 Waiver, were more likely to lose full-benefit Medicaid coverage. For individuals in the medically needy eligibility category, our data analysis finding echoes experts interviewed in this study who would expect coverage loss to be most likely among this group because their eligibility is contingent on continually incurring high medical expenses. For those eligible for Medicaid coverage under Section 1115 Waivers, the data analysis shows results contrary to the expectations of experts, who would anticipate less coverage loss in this group because beneficiaries in this group are likely to be assisted by case managers for re-enrollment to receive LTSS in the community. It is possible that the higher rates of coverage loss in these eligibility groups are due to more onerous recertification and renewal processes, as compared to those in the SSI-cash category.

Nationally, our data analysis also reveals a substantial difference in the number of people who have any loss of coverage for 1 month or more (29.1%), compared to those who lose coverage for longer than 3 months (21.1%). The difference between these two numbers suggests that 8% of all new full-duals experienced a short break in full-dual coverage, less than 3 months, over the 12-month period following their initial transition to full-dual status. It is likely that a substantial portion of the observed coverage loss is temporary and administrative in nature, which could be resolved by improving application and recertification procedures.[4] Some of the coverage loss may also be due to income or asset fluctuation. However, even among people who qualified for Medicaid by receiving SSI-cash benefits, the group with the greatest stability in maintaining continuous dual eligibility coverage, there still is a substantial short-term coverage loss. Although not able to quantify it, subject matter experts interviewed in this study thought that coverage loss was more likely related to administrative requirements, which vary by state. Due to data constraints, we were unable to document state-specific administrative requirements, which should be further explored in future research.

Our research considers data from the period prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA modified Medicaid eligibility criteria (in expansion states), the requirements for eligibility redetermination, and eased the Medicaid enrollment process for individuals. These changes included requiring a single point of entry for Medicaid and Exchange enrollment in addition to the utilization of electronic data sources to verify an individual's eligibility (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013). Experts interviewed had mixed opinions about the potential impacts of the enrollment and eligibility provisions of the ACA on the dually eligible population. A few experts noted that the creation of the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office within CMS, as well as the push to better align care for the dual eligible population through activities including the Financial Alignment Initiatives, might impact the stability of an individual's full-dual status. Some respondents believed that the changes in enrollment and recertification processes would not impact this population due to specific enrollment requirements including the look-back period. This is because the electronic verification systems would be unable to verify an individual's assets. However, others noted that spillover from policies targeted at the nonaged, blind, and disabled population could occur and states may make the redetermination process less burdensome for dual eligible beneficiaries. In fact, state Medicaid officials interviewed in this study shared that changes in renewal procedures because of spillover from the ACA had impacted older people and persons with disabilities. These included providing all individuals with prepopulated renewal forms to ease the burden on beneficiaries and extending the 90-day grace period to older people and persons with disabilities.

4.2. Conclusion

High "churning" in dual eligible status is problematic for both individual beneficiaries and providers. For dual eligible beneficiaries, the loss of full-benefit Medicaid coverage is of concern because most of them do not have an alternative source of health insurance for the services covered by full-benefit Medicaid (Ku & Steinmetz, 2013; Riley et al., 2014). Without Medicaid support, many of these low income individuals may have difficulty paying for cost-sharing of Medicare services and may be unable to access services that are not covered by Medicare (such as LTSS). For providers involved in the care of dual eligible beneficiaries, discontinuity in full-benefit Medicaid coverage may lead to financial losses.

This policy brief documented the frequency of Medicaid coverage loss among full-benefit dual eligible beneficiaries and identified potential causes for coverage loss using a mixed methods approach. Almost one-third of new, full-duals lost their full-dual status within 12 months of initial transition to that status. Nearly one-third of those who lost coverage did so for 3 months or less, which may represent temporary coverage loss that is due to administrative requirements. Our analysis further found wide variation in the rates of full-benefit Medicaid coverage loss across states, and this variation seems to be driven in part by state-specific Medicaid eligibility policies. Our results suggest that states with more inclusive Medicaid eligibility coverage policies tend to have less coverage loss among new, full-duals than states with more restrictive Medicaid coverage. Future research should be done to identify state-specific administrative requirements for enrollment and renewal procedures among older persons and individuals with disabilities that may adversely affect maintenance of their eligibility.

5. REFERENCES

Accius, J., L. Flowers, and B. Flinn. 2017. "Fact Sheet: Low-Income Medicare Beneficiaries Rely on Medicaid for Critical Help." AARP Public Policy Institute.

Administration on Aging. 2017. "Medicaid Estate Recovery" [accessed on June 19, 2017]. Available at: https://longtermcare.acl.gov/medicare-medicaid-more/medicaid/medicaid-estate-recovery.html.

Buccaneer. 2015. "Medicare-Medicaid Linked Enrollee Analytic Data Source (MMLEADS Version 2.0): User Guide." Buccaneer, Systems and Service, Inc.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2015. "Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office Fiscal Year 2015 Report to Congress" [accessed on June 6, 2017]. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination-Office/Downloads/MMCO_2015_RTC.pdf.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2016. "Data Analysis Brief: Medicare-Medicaid Enrollment from 2006 through 2015" [accessed on June 2, 2017]. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination-Office/Downloads/DualEnrollment_2006-2015.pdf.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2017. "About Section 1115 Demonstrations" [accessed on June 19, 2017]. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/about-1115/index.html.

Feng, Z., A. Vadnais, E. Vreeland, S. Haber, J.M. Wiener, and B. Baker. 2017. "Analysis of Pathways to Dual Eligible Status." Final report prepared for Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2013. "Medicaid Eligibility, Enrollment Simplification, and Coordination under the Affordable Care Act: A Summary of CMS's March 23, 2012 Final Rule" [accessed on June 2, 2017]. Available at: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/8391.pdf.

Ku, L., P. MacTaggary, F. Pervex, and S. Rosenbaum. 2009. "Improving Medicaid's Continuity of Coverage and Quality of Care." Report prepared for the Association for Community Affiliated Plans.

Ku, L., and E. Steinmetz. 2013. "Bridging the Gap: Continuity and Quality of Coverage in Medicaid." Washington, DC: George Washington University.

McMahon, S., M. Crawford, and C. Heiss. 2013. "Implementation of the Affordable Care Act's Hospital Presumptive Eligibility Option: Considerations for States" [accessed on June 2, 2017]. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/mac-learning-collaboratives/learning-collaborative-state-toolbox/downloads/state-network-chcs-implementation-of-the-affordable-care-acts-hospital-p.pdf.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MedPAC & MACPAC). 2017. "Data Book: Beneficiaries Dually Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid." Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/publications/jan17_medpac_mac….

Riley, G.F., L. Zhao, and N. Tilahun. 2014. "Understanding factors associated with loss of medicaid coverage among dual eligibles can help identify vulnerable enrollees." Health Aff(Millwood) 33(1): 147-52.

Social Security Administration (SSA). 2014. "SI 01715.010 Medicaid and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) Program" [accessed on June 22, 2017]. Available at: https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0501715010.

Stone, J. 2011. "Medicaid Eligibility for Persons Age 65+ and Individuals with Disabilities: 2009." Congressional Research Service.

Stuart, B., and P. Singhal. 2006. "The Stability of Medicaid Coverage for Low-Income Dually Eligible Medicare Beneficiaries." Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Walker, L., and J. Accius. 2010. "Access to Long-Term Services and Supports: A 50-State Survey of Medicaid Financial Eligibility Standards. Washington DC: AARP. Available at: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/ltc/i44-access-ltss_revised.pdf.

Young, K., R. Garfield, M. Musumeci, L. Clemans-Cope, and E. Lawton. 2013. "Medicaid's Role for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries" [accessed on June 2, 2017]. Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaids-role-for-dual-eligible-beneficiaries/.

APPENDIX A. ADDITIONAL TABLES

| TABLE A-1. State Medicaid Eligibility Policies for Older People and Individuals with Disabilities, 2009 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | 209(b) | Special Income Limit | Miller Trust | Medically Needy Coverage | Medically Needy Coverage, Including HCBS |

Poverty-Level Coverage |

| AK | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| AL | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| AR | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| AZ | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes |

| CA | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CO | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| CT | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| DC | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| DE | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| FL | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| GA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| HI | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| IA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| ID | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| IL | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| IN | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| KS | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| KY | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| LA | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| MA | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| MD | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| ME | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| MI | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| MN | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| MO | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| MS | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| MT | No | No | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| NC | No | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| ND | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| NE | No | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| NH | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| NJ | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| NM | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| NV | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| NY | No | No | NA | Yes | Yes | No |

| OH | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| OK | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| OR | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| PA | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| RI | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| SC | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes |

| SD | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| TN | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| TX | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| UT | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| VA | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| VT | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| WA | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| WI | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| WV | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| WY | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | No |

| SOURCE: Walker and Accius, 2010. NOTE: States are only able to establish a Miller Trust if they have established Special Income Limit as an eligibility category. In data analysis, Not Applicable (NA) is coded as No. |

||||||

| TABLE A-2. Variables and Descriptive Statistics of Study Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Description | Number | Percent |

| TOTAL | 2,580,092 | 100.0 | |

| Age | |||

| <65 | 1,178,424 | 45.7 | |

| >65 | 1,401,668 | 54.3 | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1,540,324 | 59.7 | |

| Male | 1,039,739 | 40.3 | |

| Race | |||

| White, nonHispanic | 1,530,691 | 59.3 | |

| Black | 494,616 | 19.2 | |

| Hispanic | 362,857 | 14.1 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 153,825 | 6.0 | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 23,581 | 0.9 | |

| Medicaid Eligibility | |||

| SSI | 877,279 | 34.0 | |

| Medically Needy | 459,828 | 17.8 | |

| Poverty | 433,852 | 16.8 | |

| Othera | 691,868 | 26.8 | |

| Section 1115 Waiver | 63,141 | 2.4 | |

| Medicare Eligibility | |||

| OASI | 1,270,410 | 49.2 | |

| DI | 1,255,442 | 48.7 | |

| ESRD | 54,240 | 2.1 | |

| Temporal Pathway | |||

| Medicare-to-Medicaid | 1,702,880 | 66.0 | |

| Medicaid-to-Medicare | 730,608 | 28.3 | |

| Simultaneous | 127,647 | 4.9 | |

| State Medicaid Eligibility Policies | |||

| Poverty Coverage | Yes | 1,451,653 | 56.3 |

| No | 1,128,425 | 43.7 | |

| 209(b) | Yes | 537,358 | 20.8 |

| No | 2,042,720 | 79.2 | |

| Medically Needy Coverage | Yes | 1,888,010 | 73.2 |

| No | 692,068 | 26.8 | |

| Special Income Rule | Yes | 2,123,548 | 82.3 |

| No | 456,530 | 17.7 | |

| Miller Trust | Yes | 953,354 | 37.0 |

| No | 1,626,724 | 63.0 | |

| SOURCE: RTI Analysis of MMLEADS Data. NOTE: Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding and exclusion of unknown and missing data.

|

|||

| TABLE A-3. Predicting Loss of Full-Benefit Medicaid Coverage over 12 Months Following Initial Transition to Full-Dual Status, 2007-2009, Multivariate Logistic Regression Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | p-value | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| LCL | UCL | |||

| Individual-Level Characteristics | ||||

| Medicaid Eligibility | ||||

| Low Income SSI-Cash (reference) | ||||

| Medically Needy | 5.19 | <0.0001 | 5.13 | 5.24 |

| Low Income Poverty | 3.04 | <0.0001 | 3.01 | 3.07 |

| Othera | 1.28 | <0.0001 | 1.27 | 1.29 |

| Section 1115 Waiver | 6.63 | <0.0001 | 6.51 | 6.76 |

| Temporal Pathway | ||||

| Medicare-to-Medicaid (reference) | ||||

| Medicaid-to-Medicare | 0.60 | <0.0001 | 0.60 | 0.61 |

| Simultaneous | 1.14 | <0.0001 | 1.12 | 1.16 |

| Original Reason for Medicare Eligibility | ||||

| OASI (reference) | ||||

| DI | 1.49 | <0.0001 | 1.47 | 1.51 |

| ESRD | 1.64 | <0.0001 | 1.61 | 1.68 |

| Age | ||||

| 65+ (reference) | ||||

| <65 | 1.64 | <0.0001 | 1.62 | 1.66 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female (reference) | ||||

| Male | 1.25 | <0.0001 | 1.25 | 1.26 |

| Race & Ethnicity | ||||

| White, nonHispanic (reference) | ||||

| Black | 1.03 | <0.0001 | 1.02 | 1.04 |

| Hispanic | 1.02 | 0.0018 | 1.01 | 1.03 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.86 | <0.0001 | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1.02 | 0.2077 | 0.99 | 1.05 |

| State Policies | ||||

| 209(b) | 1.22 | 0.2291 | 0.88 | 1.69 |

| Poverty Coverage | 0.58 | 0.0001 | 0.44 | 0.77 |

| Medically Needy | 0.92 | 0.5699 | 0.68 | 1.24 |

| Special Income Rule | 1.44 | 0.0763 | 0.96 | 2.16 |

| SOURCE: RTI Analysis of MMLEADS Data. NOTE: N = 2,511,737.

|

||||

NOTES

-

This refers to 2006-2010, the period for data analysis reported in this brief. In 2014, Indiana became a 209(b) State. Currently, 40 states use SSI criteria to determine Medicaid eligibility.

-

A potential bias of this approach for the results is that individuals who died in the 12 months following their transition (excluded from our analysis) may have higher medical expenses and therefore less likely to lose Medicaid eligibility due to high need.

-

This analysis measures the loss of full-benefit dual eligible status including the loss of Medicaid and Medicare benefits. We expect a negligible number of Medicare beneficiaries to lose Medicare coverage. Thus, we refer to the loss of full-benefit Medicaid coverage throughout this section to aid interpretation and understanding of these results.

-

In a recent story run by the Georgia Health News, a group of individuals with disabilities in Georgia sued the state for having failed to help them maintain Medicaid eligibility (available at: http://www.georgiahealthnews.com/2017/04/georgians-disabilities-required-renew-benefits-suit/). Of note, Georgia happened to be one of the states with the highest rate of Medicaid coverage loss in our study.

Analysis of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy and Data

This report was prepared under contract #HHSP233201600021I between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy (DALTCP) and the Research Triangle Institute. For additional information about this subject, you can visit the DALTCP home page at http://aspe.hhs.gov/office-disability-aging-and-long-term-care-policy-daltcp or contact the ASPE Project Officer, Jhamirah Howard, at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201; Jhamirah.Howard@hhs.gov.

Reports Available

Loss of Medicare-Medicaid Dual Eligible Status: Frequency, Contributing Factors and Implications

- HTML: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/loss-medicare-medicaid-dual-eligible-status-frequency-contributing-factors-and-implications

- PDF: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/loss-medicare-medicaid-dual-eligible-status-frequency-contributing-factors-and-implications

Analysis of Pathways to Dual Eligible Status: Final Report