Kelly Devers, Nicole Lallemand, Amanda Napoles, Brenda Spillman and Fred Blavin

Urban Institute

Gary Ozanich

HealthTech Solutions

ABSTRACT

This report provides an overview of current efforts for implementing electronic health information exchange (eHIE) by long-term and post-acute care (LTPAC) providers. The report describes the extent to which LTPAC providers are preparing for and implementing eHIE with their partners and assessing its impact. The report provides a review of the grey and published literature from the past 3 years and findings from discussions with 22 stakeholders representing 12 regions where eHIE initiatives involving LTPAC providers are completed or ongoing. The report also presents findings of in-depth case studies of three eHIE initiatives in which LTPAC providers participate (1 in Pennsylvania and 2 in Minnesota).

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization.

"Acronyms

The following acronyms are mentioned in this report and/or appendices.

| ACA | Affordable Care Act |

|---|---|

| ACC | Accountable Care Collaborative |

| ACO | Accountable Care Organization |

| ACTION | Accelerating Change and Transformation in Organizations and Networks |

| ADT | Admission Discharge Transfer |

| ALF | Assisted Living Facility |

| APCD | All-Payer Claims Database |

| API | Application Program Interface |

| ARRA | American Recovery and Reinvestment Act |

| ASPE | HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation |

| C-CDA | Consolidated-Clinical Data Architecture |

| CASPER | Certification and Survey Provider Enhanced Reports |

| CCD | Continuity of Care Document |

| CCW | Chronic Conditions Warehouse |

| CEHRT | Certified Electronic Health Record Technology |

| CIVHC | Center for Improving Value in Health Care |

| CMMI | Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation |

| CMS | HHS Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

| CORHIO | Colorado Regional Health Information Organization |

| CRISP | Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patients |

| DSM | Direct Secure Messaging |

| e-INTERACT | Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers |

| eHIE | Electronic Health Information Exchange |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| EMS | Emergency Medical Services |

| ER | Emergency Room |

| FFS | Fee-For-Service |

| FHIR | Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource |

| FOA | Funding Opportunity Announcement |

| HCBS | Home and Community-Based Services |

| HEAL NY | Healthcare Efficiency and Affordability Law for New Yorkers Capital Grant Program |

| HHA | Home Health Agency |

| HHS | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

| HIE | Health Information Exchange |

| HIMSS | Health Information and Management Systems Society |

| HIO | Health Information Organization |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| HISP | Healthcare Information Services Provider |

| HIT | Health Information Technology |

| HITECH | Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health |

| HITPAC | Health Information Technology for Post-Acute Care |

| HL-7 | Health Level Seven |

| HRSA | HHS Health Resources and Services Administration |

| ICD-9 | International Classification of Diseases, ninth version |

| IDN | Integrated Delivery Network |

| IDSN | Integrated Delivery System or Network |

| IHIE | Indiana Health Information Exchange |

| IMPACT | Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| IRF | Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility |

| KeyHIE | Keystone Health Information Exchange |

| LAND | Local Adopter for Network Distribution |

| LTCH | Long-Term Care Hospital |

| LTPAC | Long-Term and Post-Acute Care |

| MAX | Medicaid Analytic Extract |

| MDH | Minnesota Department of Health |

| MDS | Minimum Data Set |

| MeHI | Massachusetts eHealth Institute |

| MiHIN | Michigan Health Information Network |

| MSIS | Medicaid Statistical Information System |

| MU | Meaningful Use |

| NF | Nursing Facility |

| NH | Nursing Home |

| OHIP | Ohio Health Information Partnership |

| ONC | HHS Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology |

| PCC | PointClickCare |

| PCMH | Patient-Centered Medical Home |

| Portable Document Format | |

| PIPP | Performance-Based Incentive Payment Plan |

| QIO | Quality Improvement Organization |

| RCCO | Regional Care Collaborative Organization |

| REC | Regional Extension Center |

| RFP | Request for Proposal |

| RHIO | Regional Health Information Organization |

| ROI | Return on Investment |

| SEE | Surrogate Electronic Health Record Environment |

| SHADAC | State Health Access Data Assistance Center |

| SIM | State Innovation Model |

| SNF | Skilled Nursing Facility |

| T-MSIS | Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System |

| TEFT | Testing Experience and Functional Tools |

Executive Summary

In this report, we describe findings related to electronic health information exchange (eHIE) involving long-term and post-acute care (LTPAC) providers. These questions cover three general areas: preparing for eHIE between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners, implementing eHIE between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners, and assessing the impact of those activities.

We addressed these questions through several methods, including:

-

A review of grey and published literature from the past three years.

-

Discussions with 22 stakeholders representing 12 regions where eHIE initiatives involving LTPAC providers are completed or ongoing.

-

In-depth case studies of three eHIE initiatives in which LTPAC providers participate (one project in the Northcentral and Northeast regions of Pennsylvania and two projects in and around Minneapolis, Minnesota).

Awareness is growing that LTPAC providers play a critical role in care coordination and related payment and delivery system reforms intended to improve quality and reduce costs. These include accountable care organizations (ACOs), hospital and post-acute care bundling, various integrated care delivery models, and Medicare's hospital readmission policy.1 eHIE between LTPAC providers and other providers is a promising and important strategy for achieving the goals of improving care coordination and quality, and reducing the cost of care.

Yet, despite the increased focus on the importance of LTPAC providers in the care continuum, results from this project indicate that integration into electronic data exchange is still in its infancy even among providers who were eligible to participate in the electronic health record (EHR) Incentive Programs. A recent Government Accountability Office report, for example, described 18 selected eHIE initiatives as being in their infancy.2 Moreover, integration of LTPAC providers into eHIE activities is generally not the robust, bidirectional exchange typically envisioned in earlier studies regarding the potential for improvements in care delivery and outcomes.3

LTPAC providers were sometimes involved in discussions and planning for eHIE in the region, However, LTPAC providers typically were not prioritized for early eHIE efforts by providers eligible for meeting meaningful use (MU), which required eHIE to meet Stage 1 and Stage 2 MU criteria for the Medicare/Medicaid EHR Incentive Programs. Additionally, since LTPAC providers were not eligible for Medicare and Medicaid EHR incentives, they often did not have certified EHR technology, necessary modules to support eHIE, or other technology solutions that would be needed to support exchange. Finally, some LTPAC providers and their trading partners were not yet convinced of the business case for exchange and/or wanted additional support (financial and technical) to implement EHRs, redesign workflows, and educate and train staff. While the fax and telephone have major limitations, moving to certified EHRs and eHIE is a significant challenge for LTPAC providers, their exchange partners, and any intermediary (e.g., Health Information Organization or vendor).

Despite these challenges, our stakeholder interviews and review of the gray literature identified 12 regions around the country where LTPAC providers are involved in the planning or implementation of eHIE and have started to engage in eHIE with key exchange partners. We conducted stakeholder discussions with stakeholders at the following organizations:

- Office of e-Health Initiatives (Tennessee);

- New York State Department of Health (New York);

- Keystone HIE (KeyHIE) (Pennsylvania);

- Massachusetts eHealth Institute (MeHI) (Massachusetts);

- Colorado Regional Health Information Organization (CORHIO) (Colorado);

- HealthInfoNet (Maine);

- Missouri Health Connection (Missouri);

- Michigan Health Information Network (MiHIN) (Michigan);

- Stratis Health (Minnesota);

- Ohio Health Information Partnership (OHIP) (Ohio); and

- Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patients (CRISP) (Maryland).

The implementation of eHIE solutions between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners has been shaped by several factors including: the exclusion of LTPAC providers from MU Medicare/Medicaid EHR Incentive Program eligibility, an installed-base of technologies for the electronic reporting of administrative data (minimum data set, Outcome and Assessment Information Set), regional variation in the technical approaches to eHIE, the degree of hospital system competition and vertical integration within a region, financial resources for eHIE, and the strategies of national and regional LTPAC chains with facilities within a region.

In places where early progress has been made, the implementation experience has been slow and mixed. The challenges of creating an affordable, feasible and usable technological solutions is difficult--more difficult than many anticipated. As we describe further in this report, the technological solutions pursued have leveraged EHR technology that key exchange partners eligible for MU Medicare/Medicaid EHR Incentive Programs have developed, such as view-only portals, or eHIE efforts developed for other providers and now adding on LTPAC providers. Other implementation challenges have been changing technology, leadership turnover at key organizations, workflow redesign, provider concerns and misconceptions about federal and state privacy and security laws, and education and training. Other implementation challenges noted include competitive pressures and demands, lack of trust among some trading partners, and in some case legal concerns.

Lack of funding and the business case for LTPAC providers to participate in robust information exchange has led to use of opportunistic and often very local solutions. Even in markets where relatively robust exchange is occurring for acute care providers, including hospitals, laboratories, and outpatient care in clinics and physician offices, LTPAC providers most often are limited to view-only access to clinical documents and partial solutions that may be helpful short-term solutions (e.g., provider and hospital portals) but reduce incentives for adopting more robust, interoperable EHR systems.

However, a wave of new federal demonstrations and funding opportunities (e.g., ACOs, health information exchange (HIO) grants from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology and requirements and incentives is influencing eHIE initiatives and the states and providers that choose to participate in those initiatives, and could potentially encourage more widespread use of eHIE among LTPAC providers. For example, the presence of ACOs in many local markets across the United States is prompting some ACOs and key participants in portions of them (e.g., hospitals) to reach out to LTPAC providers and conversely LTPAC providers in those communities to develop eHIE capacity as a way to ensure that referrals from local hospitals continue in the future. The Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act also has the potential to accelerate LTPAC provider involvement in HIE through its provisions intended to encourage interoperable HIE with and by requirements for LTPAC providers reporting.

A potential wildcard in predicting LTPAC involvement in eHIE initiatives going forward is the technology used to engage in eHIE. Findings from the literature review, stakeholder discussions, and case studies suggest that those interested in advancing LTPAC involvement in eHIE initiatives should not wait for a so-called "silver bullet" that will produce seamless exchange between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners. Instead, findings suggest that the likely near-term migratory path going forward will involve Direct Secure Messaging, view-only portals through hospitals and HIEs, and, due to considerable regional variation, smaller implementation efforts and assessment of their impacts (i.e., test of specific use cases). Other new innovative pathways, such as Transform, surrogate exchange environment, application program interface, and EHR, offer promising but more mid-term and long-term solutions.

Overall, progress is being made in involving LTPAC providers in efforts to engage in eHIE across the United States. New technology solutions offer better opportunities for more robust eHIE involving a wider swath of LTPAC providers. And new policy and market dynamics are convincing LTPAC providers, hospitals, medical groups, and other providers of the value to including LTPAC providers in eHIE efforts and are facilitating more robust eHIE more generally. Relatively little research is available on the impact of these eHIE exchange efforts because of the early stages of eHIE between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners, and there also are number of methodological challenges to these studies. However, the time is ripe for targeted research and evaluations to continue learning about what works and what does not work in eHIE initiatives involving LTPAC providers. The Urban Institute team describes promising approaches to conducting a targeted quantitative impact evaluation using ACOs or integrated delivery systems or networks. The results of such an evaluation as well as other evaluations already underway will help to identify and spread promising approaches to eHIE involving LTPAC providers across the country.

Purpose and Background

There is growing awareness that long-term and post-acute care (LTPAC) providers play a critical role in care coordination and related payment and delivery reforms intended to improve quality and reduce costs, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), hospital and post-acute care bundling, and Medicare's hospital readmission policy. Additionally, timely electronic health information exchange (eHIE) between LTPAC providers and other providers is a promising and critical strategy for achieving these care coordination, quality improvement, and cost reduction goals.

Long-Term and Post-Acute Care Providers

LTPAC providers include a wide range of providers, such as: long-term care hospitals (LTCHs), inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), skilled and unskilled nursing facilities (NFs),4 and home health agencies (HHAs). Other providers that deliver related home and community-based services (HCBS) include hospice, assisted living facilities (ALFs), and adult day care. LTPAC and HCBS providers vary by relative emphasis on: (1) medical versus social service needs; and (2) restorative and recuperative services versus services intended to maintain functioning or slow deterioration (or in the case of hospice service the delivery of palliative care).

This project focuses on skilled and unskilled nursing facilities and HHAs to the extent possible. In addition to the request for proposal (RFP) requesting such a focus, NFs and HHAs are a major component of the LTPAC provider segment, with a relatively large number of facilities, beds, and residents/patients that are transitioning to and from other health care providers, such as hospitals. Below we provide additional information about LTPAC providers, their adoption of electronic health records (EHRs), and a conceptual framework for understanding eHIE involving LTPAC providers.

According to data from the American Health Care Association, there are 15, 632 certified NFs and 1,368,351 patients in certified beds in the United States.5 In 2012, approximately 3% of the over 65 years of age United States population resided in nursing homes (NHs), and approximately 11% of the 80 years of age United States population resides in NHs.6 Further, these segments of the United States population are growing and so NF use as well as use of alternative care settings will rise.7

Home health care is another LTPAC setting that offers a possible alternative to NF care and is a segment of the LTPAC provider market that is also growing rapidly.8 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) data indicates that as of 2010 there were 12,311 HHAs, and 3.4 million beneficiaries receiving home health services in the United States.9

A recent issue brief by CMS, titled Medicare Post-Acute Care Episodes and Payment Bundling,10 also provides some critical information about the volume and nature of transitions of care between hospitals and LTPAC providers. Specifically, the report notes that:

-

Nearly 40% of patients discharged from the hospital received post-acute care.

-

14.8% of those patients are readmitted to an acute hospital within 30 days.

-

Use of multiple post-acute care sites within 60 days is common occurs in more than half (50.5%) of post-acute care users.

Clearly, there is a major opportunity to improve the quality, safety, and efficiency of care as patients move through the continuum of care from acute to post-acute and long-term care and the various facilities and settings in which such services are provided. LTPAC provider engagement in eHIE could potentially help to achieve improvements in quality, safety and efficiency.

But what do we know about the certified EHR capabilities of LTPAC providers, particularly NFs and HHAs? There are no nationally representative data available about the current state of certified EHR adoption and eHIE by LTPAC providers.

It is very difficult to determine current rates of EHR adoption by LTPAC providers from prior studies because the best available evidence was collected before 2009.11 Additionally, our research indicates that there is not a shared definition between LTPAC providers and their trading partners of what functionality constitutes an EHR. For example, LTPAC providers appear to indicate that the ability electronic reporting of demographic and financial data is health information exchange (HIE), while their trading partners indicate that clinical data exchange and re-use as defined under Meaningful Use (MU) is the appropriate definition. Finally, other aspects of the methods and data, such as sample frames and sizes, differ substantially across studies.

Purpose of the Study

The general purpose of this project is to study and learn from early efforts to prepare for and implement eHIE between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners (e.g., hospitals, medical groups, pharmacies, and their staffs). This includes learning from the experiences of health plans (e.g., Medicare Advantage, Medicaid agencies, Medicaid managed care plans, and commercial plans), HIEs, state policy officials, and evaluators of eHIE initiatives in addition to the experiences of LTPAC providers and their exchange partners. This project also includes developing a plan for quantitatively assessing the impact of eHIE among these providers and their trading partners on key outcomes such as 30 day post-hospital discharge readmission rates, hospital admission rates from the emergency room (ER), and total Medicare resource utilization. More specifically, the project seeks to answer the following six major research questions:

-

What community characteristics and/or programs (e.g., service delivery and payment models, special initiatives, collaborations, etc.) enabled and continue to support the electronic exchange of health information between LTPAC providers and their HIE trading partners (e.g., physicians, hospitals, pharmacies/pharmacists, etc.)? What was/is the focus of these activities (e.g., improving coordination/continuity of care, increasing efficiencies and reducing costs, identifying information exchange needs, building trust, etc.)? Over what period of time were these activities implemented prior to and during implementation of HIE activities?

-

What types of health information do the LTPAC providers and their trading partners need to support continuity and coordination of care; and how were these information needs identified? What types of information do the LTPAC providers and their trading partners create and transmit? How has the type and timing of information exchange changed since implementing eHIE?

-

What business/organizational/quality/other factors lead to the LTPAC provider's decision to engage and invest in eHIE? What eHIE methods (i.e., what technology solutions) are used to transmit information to/from the LTPAC provider and their HIE trading partners? Does the method of exchange enable the interoperable exchange and re-use of needed clinical information? What are the costs of the technology solutions?

-

What activities (e.g., technological, policy, financial and human workflow) were undertaken by the LTPAC provider to prepare for and enable the provider/staff to engage in eHIE?

-

How has the creation, transmission, and receipt of eHIE (including interoperable exchange) at times of transitions in care and during instances of shared care impacted the clinical workflow in the LTPAC settings and that of their clinical trading partners (i.e., physicians, hospitals, and pharmacies/pharmacists)? What do the LTPAC providers and their trading partners describe as being the advantages and disadvantages of engaging in eHIE with LTPAC providers?

-

What is the measureable impact of eHIE on the quality, continuity, and cost of care for: (1) the LTPAC providers; and (2) their HIE trading partners? For example, how has eHIE affected 30 day post-hospital discharge readmission rates; hospital admission rates from the ER; and total Medicare resource utilization? What is the average number of eHIE message transmissions per LTPAC admission and discharge? Can the analyses being undertaken in selected communities be extended; and if so, how? Can these analyses be applied in other communities, and if so, how?12

As described further below in the methods, data, and findings sections, the scope and degree of exchange involving LTPAC providers was less than anticipated at the project's start. While our study was able to explore questions related to preparation for and implementation of eHIE involving LTPAC providers; our study was only able to partially address some of the research questions related to the impact of eHIE involving LTPAC providers on quality, continuity, cost of care, and workflow. Nonetheless, our team has developed a feasible, high-level quantitative and mixed research method plan for studying the implementation and impact of eHIE between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners that will help address other pressing questions in the near term.

The rest of this report is organized as follows. We first describe the rich methods and data sources used, specifically a review of the literature, conversations with stakeholders involved with eHIE initiatives with LTPAC providers, and in-depth case studies in two states (Minnesota and Pennsylvania). Then, we describe and discuss our findings from a structured literature review, stakeholder discussions, and case studies conducted in Minnesota and Pennsylvania (two eHIE initiatives in Minnesota and one in Pennsylvania). The sections describing the findings are organized by three topic areas: preparation, implementation, and evaluation. We also introduce each of these sections describing the specific research questions that are answered within that section. We sought to triangulate findings from the literature review, stakeholder discussions, and case studies, but in some research we obtained limited information from one data source. For example, the literature review yielded little information about the implications of eHIE involving LTPAC providers on human workflow (in terms of both preparation activities and impact). These areas are noted in the text to the extent possible. In each section we highlight where findings from the data sources were consistent with each other and where findings diverged. We close with a discussion of issues to consider in advancing eHIE involving LTPAC providers and evaluating the impact of those efforts on quality, cost, and utilization.

Conceptual Framework

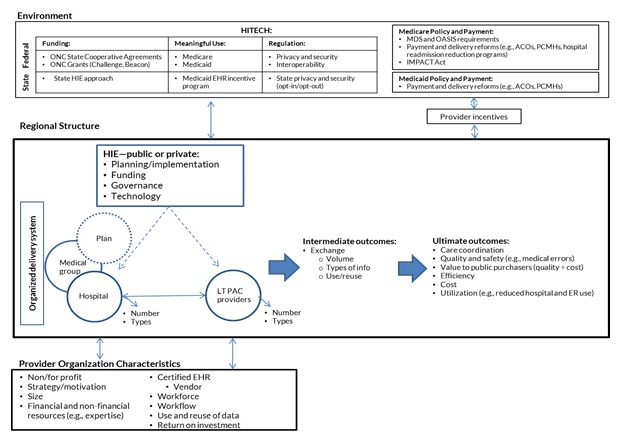

To address the six major research questions and guide our case studies and quantitative plan, we developed a conceptual framework (Figure 1 below) based on our stakeholder discussions and literature review. Conceptual frameworks identify concepts of importance for addressing the research questions and the hypothesized relationships between them. They also can help clarify the different levels or units of analysis (i.e., national, state, regional, organizational, individual providers, patient population or sub-populations). Although this conceptual framework was based on our findings from the stakeholder discussions and literature review, described in detail in the "Methods" below, we introduce and provide an overview of the conceptual framework here because it informed our selection of states and regions for case studies and it also provides a roadmap for our background and findings sections.

| FIGURE 1. Conceptual Framework for Studying eHIE Involving NH and Home Health Providers |

|---|

|

Several aspects of our conceptual framework are noteworthy. First, our conceptual framework is comprised of three major "levels." These include:

-

The environment or context (top row) in which specific regional eHIE efforts between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners are occurring. In general, this environment or context consists of major federal and state policies that are shaping eHIE and the behavior of LTPAC providers and their exchange partners. As Figure 1 shows, there are three major sub-components of the policy environment: American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH), Medicare Policy and Payment, and Medicaid Policy and Payment.

As described in the background and overview section and further below in our findings sections, ARRA HITECH programs have been the primary driver of eHIE efforts in various states and regions through particular programs such as the state HIE cooperative agreements and the Medicare and Medicaid EHR payment incentive programs. Although the state HIE cooperative agreements have largely ended, their experience and degree of success continues to shape whether and what kind of opportunities for eHIE that LTPAC providers and their exchange partners currently have in the region. In 2014, the HHS Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) also developed and released a ten-year vision to achieve Interoperable health information technology (HIT) infrastructure, prioritizing strategies and activities required to achieve interoperable exchange in the short and longer terms, including greater consumer and patient engagement.13

The Medicare and Medicaid EHR incentive programs defined the MU in stages and gave eligible hospitals and professionals (e.g., hospitals and medical groups but not LTPAC providers) incentives to adopt and use certified EHRs and engage in eHIE. Stage 2 MU in particular gave eligible hospitals and professionals greater incentive to engage in eHIE generally, so some began to engage in eHIE with LTPAC providers. Proposed modifications to MU in 2015-2017 and the proposed Stage 3 MU rules were released in April 2015 and the final rule was released on October 6, 2015. The 2015-2017 modifications restructures Stages 1 and 2 MU to: align them with Stage 3 in 2017 or 2018; refocus the existing program toward more advanced use of EHR technology; and align the required reporting periods for providers to support a flexible, clear framework, ensuring sustainability of the Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive programs. All providers will be reporting at the Stage 3 level by 2018 regardless of previous progress.14 Overall, the 2015-2017 and Stage 3 rules provide even further incentive for eHIE as the requirements related to eHIE have increased.

Finally, ONC and others at the federal and state levels have been working to further clarify, develop and strengthen privacy and security policies. Challenging issues remain in this area (e.g., trust and authentication protocols for providers, legal liability for data exchanged and accepted into an EHR, patients' ability to opt-out and/or access and control some or all of the information about their health).

Similarly, as shown to the right in the top row of Figure 1, there are major Medicare and Medicaid policy and payment changes underway that are shaping LTPAC providers and/or their trading partners incentives to engage in eHIE with one another. For example, both Medicare and Medicaid have a variety of provider payment and delivery system reform initiatives fully implemented (e.g., hospital readmission penalties) or underway (e.g., ACOs, patient-centered medical homes [PCMHs], Health Homes) that provide greater incentives to hospitals and medical groups to consider engaging in exchange with LTPAC providers. Conversely, Medicare requires LTPAC providers to collect and report assessment data such as the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) data for home health patients and Minimum Data Set (MDS) data for NH patients and the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act also places additional requirements to standardize and make interoperable assessment data elements in LTPAC settings.

In some markets, private health plans with products and populations that may require NH care (e.g., Medicare Advantage Plans, Medicaid managed care organizations for certain sub-populations) are seeking to create preferred provider networks with LTPAC providers and require a willingness and ability to engage in eHIE to be in that preferred network.

Collectively, these major policy and payment areas can create greater financial and non-financial incentives for LTPAC providers and their partners to participate in eHIE.

Finally, it's important to note that in order for eHIE to occur, both parties (i.e., sender and receiver) have to be willing and able to engage in exchange. As we describe, sometimes there is a misalignment of incentives or willingness and ability between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners, so exchange does not happen at all or is constrained to particular uses and/or technological approaches. This is particularly true at this relatively early point in certified EHR adoption and use by Medicare/Medicaid EHR Incentive Program MU eligible providers, relatively limited availability of certified EHR technology (CEHRT) and use by LTPAC providers, and the early and rapidly changing nature of eHIE approaches in health care.

-

The characteristics of the region in which eHIE between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners are taking place (middle row). Of particular importance at this level are: (1) whether the region had developed a functioning and independent health information organization (HIO) and, if so, whether it was funded with federal and state funds or it was privately funded, what technological solutions it employs, and if it can be sustained; (2) the structure of the health plan, hospital, medical group and LTPAC markets; and (3) the financial and non-financial incentives present in the specific market, including things like provider payment and delivery reforms and or other major demonstrations, grants, or projects that are taking place.

Many of the regions in which we found early eHIE efforts between LTPAC providers had a relatively successful HIO (i.e., at least operationally, even if engagement with and involvement of LTPAC providers was still in the early phases) and/or one or more large integrated delivery system or network (IDSN) that dominated the market. As we describe further, in both of our case study states and regions, large IDSNs were either a founding member and sponsor of the public or private HIE (e.g., Geisinger helping start and support KeyHIE (Keystone HIE) in Pennsylvania) or served as an HIO and eventually become the certified HIO in the region or state (i.e., Allina in Minnesota).

When the HIO is either supported or closely aligned with an IDSN, it is important to consider the specific type or components of the IDSN (e.g., does it own and operate a health plan? Is it also operating as an ACO?) because these likely shape the systems incentives for and approach to engaging in eHIE with LTPAC providers, their ability to lead and organize an eHIE initiative in the region and sometimes state, and how their HIO or IDSNs actions are perceived.

Some IDSNs dominate the regional market and are perceived to have the financial resources and technical expertise to not only adopt and use EHRs but to either support a public HIO or serve as the HIO itself. However, in some case other providers fear that those IDSNs will use the information in the HIO to gain greater market power, for example, by strategically using the information in the HIO to assess referral patterns, performance of other organizations, and risk of various sub-populations. So, as one respondent noted, "eHIE often moves at the speed of trust."

Similarly, the structure of the LTPAC organizations that are not owned by the IDSN is important also. If the LTPAC providers are not owned by IDSNs, are they part of national chains (which are typically for-profit), smaller regional chains, or single or quite small providers (e.g., "mom-and-pops")? There is significant variation across regions in the structure of the LTPAC providers and their exchange partners and the hence the incentives (financial and non-financial) that they have to engage in exchange, the perceptions of the business case and/or return on investment (ROI) for adoption certified EHRs and engaging in eHIE in specific regions and states, as well as what technological solutions that are available and most desirable.

Finally, it important to note that when a public or private HIO is successfully operating, there is pressure to develop a funding mechanism and technological solution that is viable in the particular region. Initially, Medicaid and private health plans were thought to be an additional and longer term funding source for HIOs besides federal and state grant funds, but in some states Medicaid and private plans were less involved in eHIE efforts. More recently, Medicaid is playing a key role in some states, supporting HIOs and eHIE through 90-10 matching funds through the Medicaid EHR incentive program and related population health or Medicaid related provider payment and delivery reform efforts in the state, such as Medicaid ACOs, PCMHs, or Health Homes. Additionally, some private insurers have supported their own HIE (e.g., Blue Cross/Blue Shield in California). Many HIOs are reportedly struggling, but at least some HIOs appear to have developed viable, long-term funding models that serve as one viable mechanism and avenue for exchange moving forward. As noted, competitors are individual IDSNs and exchange with providers using the same EHR and EHR portals which we describe in greater detail in the findings sections.

-

The characteristics of the specific provider organizations (bottom row) in the region, including both the LTPAC providers and their exchange partners. Some key issues at this level are whether the organization has adopted a certified EHR, if so what kind, and whether they believe there is a strategic advantage and/or positive business case for engaging in exchange. If they believe there is a strategic advantage and/or positive business case for eHIE, there also is the question of what kind of data will be exchanged, for what purpose, and through which technological means.

The literature on EHR adoption and use points to a possible fourth level of analysis: that is the individual level. Specifically, individual providers (e.g., physician, nurse) and/or staff (e.g., managers, clerks) attitudes and views toward EHRs and eHIE may vary based on their own characteristics. For example, physician and other clinicians' age is negatively associated with willingness and ability to use an EHR or use all of its features, even when the practice or hospital they work in has one installed.15 Similarly, patients/residents and their family or guardians view of EHRs, eHIE, and privacy and security and related issues, such as willingness to provide consent, may vary by education, income, race/ethnicity or other individual characteristics. However, we do not include this level explicitly in our conceptual framework, as we were unable to collect much data on these issues through our case studies. Nonetheless, where our respondents reported on these issues in their own organizations, we report them.

The second noteworthy feature of our conceptual framework is that it allows for bidirectional effects of each level (e.g., environment or context) on others (e.g., region or community) and how characteristics of eHIE approaches in a specific region relate to implementation and outcomes (intermediate and ultimate) over time. For example, our stakeholder discussion, literature review, and case studies show that the federal and state environment or context has affected specific regional eHIE efforts and there is great variation across regions in both the level and types of eHIE. Conversely, promising initiatives and lessons learned about eHIE between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners can be used to help implement some ongoing HITECH programs (e.g., latest round of HIE cooperative agreement, 2015-2017 rule and Stage 3, use of Medicaid 90-10 matching funds) and other payment and delivery system reforms at the state and federal levels. As Yin has noted, one of the central contributions of case studies is to better understand what aspects of the environment or context are most important and how they affect planning, implementation, and outcomes over time.16 Others have also noted the importance of "multi-level" research and evaluation to better understand the complex environment, interactions, and outcomes of new programs or interventions.17

Finally, our conceptual framework includes both intermediate and ultimate outcomes. The ultimate outcome of interest (to the far right in the middle row) cannot be achieved until robust enough exchange occurs and this is likely to take time. That is, the volume and nature of exchange occurring clearly affects the ability to achieve improvements in care coordination and quality and reduction in total costs for the population served by the organizations in the region. Additionally, the ability to use and re-use exchanged data to achieve these ultimate outcomes requires robust but affordable technological solutions as well as workflow redesign and related education and training. While LTPAC providers and their exchange partners are in the early stages of exchange, as described in further detail in our finding section, we have identified some promising states and regions throughout the country where research and evaluation on intermediate and ultimate outcomes could potentially take place. Further information on possible outcome or impact analysis can be found in the "Impacts and Evaluation" portion of the paper.

Methods

This study sought to answer the research questions listed above by conducting a systematic review of the literature (peer-reviewed and gray) over the past five years, semi-structured discussions with key informants throughout the country (N=22), and site visits to two states (the Urban Institute team studied two initiatives in Minnesota, one in Pennsylvania) in the United States where eHIE involving LTPAC providers is more advanced in planning and early implementation activities compared to most areas of the country.

The Urban Institute team used each data source for a different purpose. The literature review was used to collect information on past and ongoing efforts to plan, implement, and evaluate eHIE involving LTPAC providers that was published over the past three years. The Urban Institute team built on this knowledge by engaging in discussions with key stakeholders in eHIE initiatives involving LTPAC providers across the United States. The Urban Institute team used these discussions to explore the latest planning, implementation, and early evaluation developments in eHIE involving LTPAC providers with an eye toward identifying two communities that could be the focus of more in-depth case studies. The Urban Institute team gained further more in-depth insight into the planning, implementation, and evaluation efforts of three eHIE initiatives involving LTPAC providers by conducting case studies of those initiatives.

The Urban Institute team used the information obtained through the targeted review of the literature and key informant discussions to also develop a conceptual framework for understanding how LTPAC providers and their trading partners prepared for the implementation of eHIE, and the impact of this exchange on clinical workflow, work force, and the quality, continuity, and cost of care the LTPAC providers and their HIE trading partners. The Urban Institute team used the information gained through the review of the literature, the stakeholder discussions as well as the newly developed conceptual framework to identify several sites of eHIE activating involving LTPAC providers that could be the subject of more in-depth case studies.

Literature Review

A systematic approach was used to identify and synthesize current literature (peer and non-peer-reviewed) on the planning, implementation, and impact of eHIE, particularly as they pertain to LTPAC settings, providers, and care coordination. First, in consultation with a research librarian, search terms were developed. Second, the search terms were applied to the databases EBSCOhost, Medline and Scopus to identify relevant literature. We initially focused our initial search to the last five years (2009-2014). We also conducted a targeted review of websites from government and professional associations to identify any relevant materials. Using these two literature review approaches, the research team identified a total of 2,021 articles for review.

Researchers then reviewed abstracts. Articles published prior to 2011 (the last three years of literature) that did not meet inclusion and exclusion criteria were eliminated, reducing the total to 303 articles. Finally, the 303 full articles were reviewed by members of the research team, and extraneous articles were eliminated. This process resulted in a final set of 74 peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed articles or materials. Appendix A contains citations for all considered (fully reviewed and included) articles.

Stakeholder Discussions

The research team used the stakeholder discussions to explore the latest planning, implementation, and early evaluation developments in eHIE involving LTPAC providers with an eye toward identifying two communities that could be the focus of more in-depth case studies. Using information from informal discussions with federal officials overseeing eHIE programs and the non-peer-reviewed literature; the research team developed an initial list of informants. In total, 17 discussions were held with 22 individuals representing 12 regions around the country.

Case Studies

Using the information obtained through the literature review and key informant discussions as well as our conceptual framework (described above), the Urban Institute team identified several sites of eHIE activity involving LTPAC providers that could be the subject of more in-depth case studies. The sites selected for more in-depth case studies were chosen in part because their markets for exchange between LTPAC providers (especially NFs and HHAs) and their exchange partners were considered relatively mature. The Urban Institute team developed and used a number of criteria in conjunction with the project officer's input to select alternative case study sites. Overall, these criteria allowed the research team to assess the potential pros and cons of various regions/states, their potential complementarity, and generalizability of case study results. For example, we sought to identify a region with a relatively mature market for exchange between LTPAC providers (especially NFs and HHAs) and their trading partners so they had more experience on which to draw and perhaps some early insights into impacts. Additionally, we considered the technological approach using, including public HIEs, private HIEs, vendor networks, and portals, allowing us to capture the diverse ways eHIE is being achieved, technologies that are more likely to be scaled up and spread (rather than unique, homegrown systems), and the implications for things like workflow and impact. Finally, we sought to identify sites that would welcome the research team.

After reviewing and discussing that list, our HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) project officer selected three initiatives across two states for case studies and site visits: KeyHIE in the Northcentral/Northeast region of Pennsylvania and the Fairview-Ebenezer and Benedictine initiatives in and around Minneapolis, Minnesota.

In summer 2015, the Urban Institute team conducted 43 interviews with 47 respondents in site visits to Pennsylvania and Minnesota. In Pennsylvania, the team held 19 interviews with 21 respondents; in Minnesota, 24 interviews with 26 respondents.

After completing the site selection process, the Urban Institute team began identifying the key organizations and informants that should be targeted for interviews during the in-person site visits as well as the most appropriate points of contact for securing those interviews. The types of informants sought for interviews included:

-

Clinical personnel such as physicians, nurses, medical assistants, office managers, and EHR/HIT staff from providers participating in the programs in the selected sites (including NFs, HHAs, hospitals, organized delivery systems, and medical groups).

-

Local and state leaders.

-

Plan and payer representatives.

-

eHIE evaluators.

-

Other stakeholders with experience and knowledge of eHIE.

To identify the most appropriate organizations and respondents for site visit interviews, the Urban Institute team used several strategies. First, the team had informal discussions with key stakeholders including state staff and, in the case of KeyHIE, HIE leadership. Second, the Urban Institute selected participating providers for interviews with the goal of having some variation in the following characteristics:

- Ownership or type (e.g., hospital or system owned, non-profit or for-profit);

- Geographic setting (urban/suburban/rural);

- Size; and

- Teaching status.

Third, the Urban Institute team inquired about other people informants thought we should interview. Through this "snowball sampling" procedure, we built a more robust list of individuals and organizations potentially able to participate in interviews.

The Urban Institute team developed and received approval from the Urban Institute's institutional review board (IRB) to use four interview protocols targeting different types of respondents. The use of four protocols (rather than one) allowed interviewers to more easily direct questions to the most appropriate respondent. For example, we directed more technical questions about a provider's technology tools toward the organization's EHR/HIE lead, and workflow related questions toward that provider's clinical staff. Since the interviews were semi-structured, interviewers were able to ask other questions and probes as needed.

The Urban Team conducted the site visits in summer 2015 using two pairs of interview teams. Each interview team consisted of a lead interviewer and a note taker. Interviews were also recorded to facilitate polishing interview notes taken during the site visit and to produce interview notes for the interviews in which there were only audio recordings. The team conducted some interviews after the site visit due to scheduling conflicts and the geographic distance of some respondents. All interview notes were cleaned and analyzed at the end of each respective site visit. In addition, during the site visit, the team discussed preliminary findings, which covered key topics to describing findings from the site visits and was used to inform the site visit memoranda. The Urban Institute team also received follow-up materials from some respondents to provide additional information on the topics covered during the interview. Findings from each site visit were summarized in memoranda.

Findings from both site visit memoranda were synthesized in the final report to illustrate how the initiatives examined overlapped and where they differed in approach and outcomes in order to identify key lessons learned and potentially generalizable findings.

|

Description of Case Study Site: Minnesota Our team studied two initiatives in Minnesota at varying stages of eHIE implementation and usage. The first was the Benedictine-Allina initiative. Exchange of patients' clinical information between the one participating Benedictine Health System (BHS) NF (St. Gertrude's) and the one participating Allina hospital (St. Francis) is performed by creating, sending, and receiving a Continuity of Care Document (CCD) using each facility's EHR. The two facilities are located on the same property, share many patients, but do not have the same EHR vendor. Exchange with other trading partners is still largely performed via fax. The second initiative is the Fairview-Ebenezer initiative, which is in the planning phases and builds off previous grant-funded work. This project focuses on improving the eHIE capacity of providers serving Burnsville, Minnesota. Fairview Health Services is the lead organization of a collaboration that includes Ebenezer and Burnsville Emergency Medical Services (EMS). Fairview owns Ebenezer but not the Burnsville EMS. Fairview-Ebenezer eHIE implementation is pending award of the State Innovation Model (SIM) testing grant. In both initiatives, hospital portals are the most common way that LTPAC providers view patient data from trading partners, which only provides information about a patient's most recent acute care encounter and is only uni-directional exchange. Minnesota was selected in part because it has a unique provider landscape. Most of the hospitals and physicians serving the region are owned or affiliated with one of several systems (e.g., Allina Health, Fairview Health Services) or multi-specialty group practices (e.g., Fairview Physicians Associates). There is also a high preponderance of LTPAC providers in Minnesota, many of which are part of senior service health systems including both initiatives studied (e.g., BHS and Fairview Health Services). Additionally, ACOs are common in Minnesota. For example, both Fairview and Allina are ACOs under CMS' Pioneer ACO Program. Minnesota's approach to eHIE is also unique. Rather than supporting a state-wide HIE or regional public HIOs, the state has taken a market-based approach to HIE, granting funds to private organizations to stand up exchange within communities. This has created a relatively decentralized and market driven model that operates within the boundaries of an overarching state plan and regulatory framework. Finally, Minnesota has implemented state laws to spur adoption of eHIE including a 2005 EHR mandate for most providers. There are also two active and influential associations in Minnesota for "older adult services" (LeadingAge and Care Providers) that have been instrumental in securing exemptions for post-acute care providers from the state's EHR mandate18 (described below) and will be contributing to the LTPAC Roadmap, which further defines the future of eHIE with LTPAC providers in Minnesota. Despite these favorable conditions, eHIE with LTPAC providers remains limited in Minnesota. |

|

Description of Case Study Site: Pennsylvania KeyHIE is a national leader in HIT. Founded in 2005. KeyHIE is one of the oldest and largest HIEs in the country. Originally under the umbrella of Geisinger Health Systems, KeyHIE is backed by decades of health care innovation and serves close to 4 million patients in the Northcentral/Northeast region of Pennsylvania. KeyHIE currently has 18 LTPAC facilities connected, and has plans to bring on an additional 55 over the next three years as part of a grant from the HHS Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). KeyHIE offers participating providers three HIT solutions: KeyHIE (query-based) Transform, MyKeyCare and is now implementing Direct Secure Messaging (DSM). KeyHIE was selected because the Northcentral/Northeast region of Pennsylvania is further advanced in implementing eHIE with LTPAC providers than most regions of the country. This is largely a result of the leadership provided by the Geisinger Health System as one of the initial sponsoring organizations for KeyHIE. Geisinger dominates the region; it currently shares data with KeyHIE and also extends its network through EpicCare Link, a portal for community providers. Finally, KeyHIE was selected because of its development and use of the Transform tool, which takes MDS and OASIS data and converts the clinically meaningful information to a CCD. This CCD can be exchanged using KeyHIE so that the all participating provides could access the CCD. The Transform tool is inexpensive relative ($500 per year for facilities with 99 beds or below) to the cost of interfacing with an exchange, which appeals to LTPAC facilities who may otherwise not be able to afford to participate in information exchange. Use of the Transform Tool is spreading to other regions and communities (e.g., Colorado, Delaware, and Illinois). |

Below, we discuss findings from the literature review, stakeholder discussions, and case studies related to

- Preparing for eHIE between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners;

- Implementing eHIE between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners; and

- Assessing the impact of eHIE between LTPAC providers and their exchange partners.

Findings: Preparing for Ehie Between Ltpac Providers and Exchange Partners

This section seeks to answer the following research questions:

-

What community characteristics and/or programs (e.g., service delivery and payment models, special initiatives, collaborations, etc.) enabled and continue to support the electronic exchange of health information between LTPAC providers and their HIE trading partners (e.g., physicians, hospitals, pharmacies/pharmacists, etc.)? What was/is the focus of these activities (e.g., improving coordination/continuity of care, increasing efficiencies and reducing costs, identifying information exchange needs, building trust, etc.)? Over what period of time were these activities implemented prior to and during implementation of HIE activities?

-

What business/organizational/quality/other factors lead to the LTPAC provider's decision to engage and invest in eHIE?

-

What activities (e.g., technological, policy, financial and human workflow) were undertaken by the LTPAC provider to prepare for and enable the provider/staff to engage in eHIE?

There was one research question in the RFP relating to cost of eHIE solutions that we were unable to answer. Federal and state grants that were used to stand up the exchange initiatives are identified in this section. However, fees used to sustain HIE were deemed proprietary information and HIEs unwilling to publicly disclose fee schedules. This section will instead focus on the costs associated with standing up eHIE in a region and the grants that supported those efforts. We will additionally discuss federal and state policies, programs and reforms that impact a regions planning for eHIE.

Funding and Financing

As shown in the environment or context (top row) level of the Conceptual Framework, federal cooperative agreements, grants, or demonstrations were the initial source of funding for eHIE initiatives with LTPAC providers. Nearly every organization that we spoke with in our stakeholder discussions and on our case study site visits, save for one, had been the beneficiary of federal funds for enabling eHIE. Specifically, cooperative agreements and grants administered through ONC programs played a major role. A few initiatives also received state funds to stand up exchange.

Though ARRA HITECH provided the initial spark for federal and state funding for EHR adoption, HIE, and MU, all of our data sources affirmed that private efforts and funding for eHIE and LTPAC providers will become increasingly critical to sustaining eHIE with LTPAC providers in the future. This means an intensified search for cost-effective eHIE solutions that show a ROI for not only Medicare and Medicaid but key provider groups that must participate in and support exchange.

Federal

Our stakeholder interviews highlighted the many sources of federal funding that HIEs could capitalize on to recruit and initiate exchange with LTPAC providers. Some HIEs leveraged funds under their State HIE Cooperative Agreement Programs. For example, some stakeholders were the recipients of ONC Challenge grants, which provided additional funds for breakthrough innovations in HIE to regions participating in the State HIE Cooperative Agreement Program.19 Four states targeted in our stakeholder discussions focused their efforts as Challenge Grant awardees on HIE involving LTPAC providers (e.g., Colorado, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Maryland).20 Similarly, several states that participated in our stakeholder discussions (e.g., Indiana, Maine, and Pennsylvania) targeted LTPAC providers as part of their Beacon Community Program Agreement efforts.21

Through our stakeholder discussions we identified one CMS Medicare Quality Improvement Organization (QIO) initiative that operated from 2012-2013 provided technical assistance to LTPAC and other providers in Colorado, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania through the HIT for Post-Acute Care Special Innovation Project (HITPAC).22 This initiative helped providers optimize their use of HIT to support medication management, care coordination in transitions of care, and advancements in HIE.23

We further studied some of the LTPAC providers involved in this initiative during our case study site visit to Minnesota. In September 2012, the Minnesota-based QIO Stratis Health was awarded a one-year $1,139,858 contract with CMS through its 10th Scope of Work24 to help NFs further adopt EHRs and work towards eHIE. After completing the HITPAC project, eHIE activities were suspended, but Ebenezer sought opportunities to keep eHIE momentum going from and continue pursuing eHIE between NFs and acute care. As a result, Ebenezer pursued a Performance-Based Incentive Payment Plan (PIPP) grant from the State of Minnesota to continue pursuing eHIE in the form of DSM, Tiger Texting, lab integration and CCD exchange (described below).

CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) Demonstration Program provides grant funds to support a variety of activities, including to identify solutions that reduce hospital admissions. Some of the stakeholders we interviewed are using these funds to pursue eHIE between hospitals and targeted LTPAC providers. For example, the Curators of the University of Missouri was awarded a Health Care Innovation Award Initiative to develop and strengthen eHIE between hospitals and NHs and HHAs.25

Finally, some states may apply for and receive SIM grants to support eHIE and related efforts with LTPAC providers. SIM grants provide funding and technical assistance to states to develop and test delivery models to improve performance and quality while decreasing costs.26 The Fairview-Ebenezer initiative studied in Minnesota, for example, sought but has not yet received a SIM Model Test Award to enable exchange of data between NFs and EMS.

As of our case study site visit, Ebenezer had received a developmental grant, which provided about one year of funding, from June 2014 to May 1, 2015. They have since solicited an implementation grant from the state, and anticipate learning whether they will be awarded funds by end of summer 2015. As of September 30, 2015 Ebenezer has not been awarded a Round 2 grant to pursue implementation of eHIE.

On the other hand, the Benedictine initiative also studied in Minnesota, was unable to apply for SIM dollars because they proposed using funds to continue developing software capabilities. Reportedly, the state cannot or will not pay for development of software capabilities through this grant.

One of our case study sites (KeyHIE) leveraged many of the federal grants described above to implement eHIE. In 2004, AHRQ awarded Geisinger a $1.5 million grant to "develop a secure web-based network that links participating hospitals and other health care providers in the region, providing seamless and secure access to patients' health information, including diagnoses, test results, allergies, and medication lists."27 In 2010, ONC awarded Geisinger a three-year Beacon Community grant totaling $16 million. Geisinger used the grant to build on its KeyHIE efforts and extend the benefits of other Geisinger-led HIT initiatives to other providers in the community.28 KeyHIE, incorporated as an independent corporation under the Geisinger Foundation in December 2013, is now its own legal corporate entity that reports to Geisinger leadership but is governed as a community resource. Soon after, in 2014, HRSA awarded KeyHIE a three-year grant for $900k to expand its network to 55 LTPAC providers in Pennsylvania. Grant funds will be used to develop on three HIT solutions within KeyHIE--KeyHIE Transform, MyKeyCare and DSM.

Some other federal resources--financial and non-financial, direct or indirect--are available to help financially support eHIE efforts generally or with LTPAC providers more specifically. For example, under the Medicaid EHR Incentive program states are eligible for a 90-10 match for certain Medicaid HIE related activities and while states cannot directly support HIE efforts with LTPAC providers, development of the HIE infrastructure may indirectly facilitate HIE between LTPAC providers and other providers over time. The 2015-2017 modifications restructures Stages 1 and 2 MU requirements for MU of certified EHRs supports settings and use cases across the care continuum. Several criteria are applicable to LTPAC providers including those around transitions of care, care plans, privacy and security, and potentially other areas.29

As note previously some of the major federal ARRA HITECH programs specifically designed to foster eHIE development and innovation came to an end (i.e., first major phase of state HIE cooperative agreements, Beacon). According to our stakeholder interviews, this has left some eHIE organizations and providers struggling to find funding sources to support further HIE infrastructure development and to sustain and expand current efforts. An ONC funding opportunity announcement (FOA) to support additional HIE efforts was released in early summer 2015. Initially only $28 million of awards were anticipated; the final FOA also resulted in ten $1 million grants for a total of $38 million in HIE investment.30 Through this effort three states (Colorado, Delaware, and Illinois) will be supporting eHIE with LTPAC providers. This level of funding is much lower than at the high of the ONC State HIE Cooperative Agreement program, which awarded $540 million.31

State

The literature identified some sources of state funding for HIE with LTPAC efforts. The most notable example is the Healthcare Efficiency and Affordability Law for New Yorkers Capital Grant Program (HEAL NY).32 HEAL NY, which started in 2006, represents more than an $800 million investment of public-private funds in EHRs and eHIE and aims to develop a health information network for New York State by linking together community-based regional health information organizations (RHIOs) that adhere to common standards and policies. RHIOs' roles included convening and governing community stakeholders, promoting collaboration and data sharing, and implementing technology for eHIE. As of 2012, 12 non-profit RHIOs provided eHIE services across New York State in compliance with state requirements using a variety of commercial products. Notably, 54% of the grantees targeted long-term care providers (though the article does not specify the types of providers falling into that category) and 24% targeted home care providers.33

The initiatives studied in our case study site visit to Minnesota were the recipient of state grants to implement eHIE with LTPAC providers. The Fairview-Ebenezer initiative was the recipient of state funds to enable eHIE with LTPAC providers. For example, they received PIPP, a two-year grant for approximately $385,000 that will end September 2016. Ebenezer is using PIPP dollars to further exchange using secure health care messaging applications such as Tiger Texting, advancing their CCD exchange with non-business affiliates and expanding exchange with state and commercial labs. The state was also a recipient of a Testing Experience and Functional Tools (TEFT) grant by CMS (about $500k) in March 2014. TEFT funded a demonstration for organizations to bring personal health records to deliver LTSS data to beneficiaries and their caregivers. One respondent noted that this state funding solicitation built on learnings from past projects such as SIM, the Fairview-Ebenezer PIPP project, and other efforts to integrate and improve care.

Benedictine was awarded $375,000 from the State of Minnesota to develop MatrixCare software such that it can exchange CCDs with Allina's Epic system peer-to-peer to support transitions of care between the Allina hospital and the Benedictine NF. The Benedictine-Allina project is primarily funded through the state grant and provider investment.

Subscription Fees

As demonstrated in the regional structure (middle row) level of the Conceptual Framework, a complement to federal funding sources, many of the initiatives studied charge a subscription fee to participants. For example, the Colorado Regional Health Information Organization (CORHIO) was an ONC Grantee (through the State Health Information Exchange Cooperative Agreement and the Challenge Grant). However, CORHIO transitioned to a $25 per user per organization subscription fees in 2014 to fund itself as ONC cooperative agreement and grant resources wound down.34 These subscription fees were not waived for LTPAC providers.

The Indiana Health Information Exchange (IHIE), a private HIE, has a subscription fee financial model as well. However, federal resources related to eHIE and policies (e.g., Stage 2 MU of the Medicaid/Medicare EHR Incentive Program) played an early role in the development of infrastructure that is now being sustained through subscription/user fees. As of December 2014, there were approximately four Kindred long-term care facilities working with IHIE, with plans to bring more on. Kindred is a national chain with 2,730 locations in 47 states.35 IHIE was initially affiliated with Regenstrief Institute, but has been an independent entity for more than two years.

KeyHIE now charges participating providers a subscription fee, priced by provider type and size, for ongoing use. This has been critical to the sustainability of the HIE since many of the federal grants that were leveraged to stand up eHIE (described above) have expired. Startup costs vary depending on the technology solution; an EHR connection can be quite expensive, particularly for larger facilities, while Transform is a much lower cost option.

The initiatives studied in Minnesota are not driven by a Health Data Intermediary or HIO, which would typically serve as a data aggregator and charge ongoing fees for connecting and querying for health information. As a result, participating facilities are not charged subscription fees. Allina, the hospital system working with Benedictine, is becoming an HIO but it envisions eHIE serving the development of their ACO and does not have plans to charge subscriptions. Providers will have to pay their vendors to develop the integration in order to connect to the HIE product. Reportedly those costs range from $2,000-30,000 per entity, which can be substantial for certain entities.

Apart from efforts to facilitate robust bidirectional eHIE, facilities involved in all of the initiatives studied reportedly have access to hospital portals to view patient information at partner organizations. These are highly affordable solutions, costing facilities only about $75/year.

Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Programs

In 2009, Congress passed the ARRA, which contained provisions collectively known as "HITECH"36 (shown in the Environment or Context level of the Conceptual Framework). The purpose of ARRA HITECH was to accelerate the digitization of the American health care system through greater adoption and the MU of EHRs and eHIE. The Medicare and Medicaid EHR incentive programs are the main mechanism through which providers, specifically eligible hospitals and eligible professionals, can access the financial resources to support the purchase or upgrade their EHRs. Additionally, through the successive stages of MU (Stages 1, 2, and 3, and for Medicaid providers only, a preliminary stage called Adopt, Implement, and Upgrade), the Medicare and Medicaid EHR incentive programs make available incentive payments to eligible providers who use certified EHR technology in the ways intended to improve the quality and efficiency of care.

Of particular importance to this project, LTPAC providers were not defined as eligible hospitals or eligible professionals under HITECH, so they were ineligible for the Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive programs or technical assistance through the Regional Extension Center (REC) program. Despite their ineligibility, the literature shows that the LTPAC provider community has worked to shape EHR Incentive Program MU criteria at the federal level. For example, per an August 1, 2012, letter from the President of American Physical Therapy Association to ONC regarding 2015-2017 modifications restructures Stages 1 and 2 MU requirements for the Medicaid/Medicare EHR Incentive Programs related to eHIE and transitions of care with LTPAC providers: "It is important that input from [LTPAC] providers is considered in the evolution of MU requirements so that patient data are accurate, accessible and transferred with the highest degree of security protocols in place to protect patient privacy."

The Federal Government has also supported policies that facilitate EHR adoption in LTPAC facilities. For example, ONC's 2014 "Health Information Technology: Standards, Implementation Specifications, and Certification Criteria for Electronic Health Record Technology, Final Rule" encourages EHR technology developers to certify EHR Modules to the transitions of care certification criteria (§170.314(b)(1) and (2)) as well as any other certification criteria that may make it more effective and efficient for eligible professionals, eligible hospitals, and critical access hospitals to electronically exchange health information with health care providers in other health care settings.37

And many of LTPAC providers' key exchange partners (e.g., hospitals, medical groups) were defined as eligible hospitals and eligible professionals and the MU requirements for the Medicaid/Medicare EHR Incentive Programs (along with other health care reforms) are beginning to give more incentive for these eligible hospitals and eligible professionals to engage in eHIE with LTPAC providers. Findings from the literature review38 and stakeholder discussions indicate that Stage 2 MU provided some incentives for eligible hospitals and eligible professionals to begin engaging in eHIE with LTPAC providers. This perspective is consistent with findings from the project's two case studies, with respondents in Minnesota also mentioning Stage 3 MU requirements as a motivating factor for hospital, organized delivery system, and medical group engagement in eHIE with LTPAC providers.

However, conversations with stakeholders across the United States indicate that competition for HIT resources within acute care provider organizations continues to be a challenge. For example, in the Missouri Quality Initiative there was an indication that organization delivery systems and hospitals were hesitant to allocate the resources needed to make DSM operational, and there was a general surprise in the technical complexity of what was required to make DSM operational. Acute care providers also continue to report staffing and information technology budget cutbacks due to financial pressures and multiple competing demands and projects. Although some HIEs indicated that the Medicaid/ Medicare EHR Incentive Program Stage 2 MU requirement for data exchange with non-affiliates was the lever used to get some acute and primary care providers as well as specialists to begin to exchange data with LTPAC providers, During this stage of the program, attestation was the priority. As a result, efforts to facilitate eHIE with LTPAC providers were often sidelined. While not specifically cited in the Pennsylvania case study, this finding is consistent with the Minnesota case study. Several respondents in Minnesota noted that provider efforts to meet MU requirements for the EHR Incentive Programs can sometimes have the opposite effect on eHIE involving LTPAC providers; in some instances, provider efforts to meet these requirements more generally have left fewer resources for developing interoperability with LTPAC providers, resulting in delays in investments in this area.

Privacy and Security Laws and Regulations

Privacy and security policies and requirements (shown in the Environment or Context level of the Conceptual Framework) are critical but can pose barriers to HIE with LTPAC providers and their exchange partners. Although all providers must meet Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and other federal privacy and security requirements, states can pass additional requirements related to privacy and security and penalties for data breaches. One important way in which state privacy and security policy varies is whether patients or their legal guardians must opt-in or opt-out of HIE (i.e., actively give consent for all or some parts of their data to be exchanged).

Opt-in policies have been found to increase the cost of HIE participation for providers and therefore decrease participation in HIE efforts, while opt-out policies decrease costs and increase provider participation. In Maine, which adopted an opt-out policy for patient consent for general medical data sharing, the eHIE includes the records of over 88% of the population. Only 1.1% of the state's population has opted out of participating in the eHIE. This is not to say that opt-in policies create an insurmountable barrier to eHIE for providers but additional thought about workflow redesign is required. For example, Massachusetts has an opt-in policy but providers reportedly have integrated the consent process into their workflows so that consent can be obtained efficiently.

This experience is consistent with findings from the KeyHIE case study. KeyHIE currently has a more restrictive approach to security than Pennsylvania requires. KeyHIE employs an opt-in privacy model, which requires providers to actively seek consent from patients in order to exchange their health information, and limits access to patient information to organizations that consent to follow KeyHIE's RHIO agreement.39 Some respondents suggested that in order to encourage greater eHIE, KeyHIE will synchronize with state laws and providers will soon be able to elect to implement the less restrictive opt-out policy. Granting this option may improve a providers' ability to actively exchange their patients' data. For example, one respondent commented that once Pennsylvania became an opt-out state in 2012, "it made things easier."

A related issue is whether and how much state privacy and security law varies from federal policies. If states do not harmonize their policies with federal law, providers must understand how the two differ and follow the more stringent policy. For this reason, Wisconsin is planning to harmonize state law with HIPAA so that no additional consent is required and patient health information is automatically included without an option for patients to opt-out. Findings from the Minnesota case study indicate that within the state there are diverse opinions on what state privacy laws and regulations require and prohibit. Interpretation of the state's HIE statute (Minn. Stat. §62J.498 sub. 1(f)),40 which defines requirements around privacy and security, varies by provider organization. Some organizations are more conservative than others. For example, some organizations could interpret the HIE law as meaning that patient consent needs to be obtained annually while others could require patient permission for each data sharing with each provider. One organized delivery system is working on moving from an opt-out to an opt-in model but has run into some "political" challenges from organization leadership in making that shift.

The Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014