Ellen Bouchery, Rebecca Morris, and Jasmine Little

Mathematica Policy Research

ABSTRACT: Although trends in substance use disorder (SUD) prevalence and treatment receipt have been relatively constant for the last decade, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) could result in a substantial increase in the number of individuals seeking or referred to treatment. The impact of parity legislation, changing perspectives about the importance of SUDs as a health condition, the opioid epidemic, and activities associated with care integration could result in additional increases in demand. In contrast the SUD treatment workforce is already challenged to meet the existing demand for treatment. A significant number of facilities reported operating at or above capacity. Low wages make hiring and retaining qualified staff a challenge. A review of the services provided to clients indicated that current practice was often inconsistent with the scientific findings on evidence-based treatment. Credentialing experts and clinical directors expressed concern about training adequacy, and the best available information suggests, at most, a small increase in training program output in recent years. Thus, overall, the SUD treatment workforce appears to lack sufficient capacity to adequately address the possible short-run increases in demand.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization.

"Acronyms

The following acronyms are mentioned in this report and/or appendices.

| ACA | Affordable Care Act |

|---|---|

| ADSS | Alcohol and Drug Services Study |

| AIDS | Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome |

| ASPE | HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation |

| ATTC | Addiction Technology and Transfer Center |

| BLS | Bureau of Labor Statistics |

| CASA | National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, Columbia University |

| CBO | Congressional Budget Office |

| CDC | HHS Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CHIP | Children's Health Insurance Program |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| CMS | HHS Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

| DSM-IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition |

| ER | Emergency Room |

| FEHB | Federal Employees Health Benefit |

| FPL | Federal Poverty Level |

| FY | Fiscal Year |

| GED | General Equivalency Diploma |

| HCUP-NIS | Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project--National Inpatient Sample |

| HHS | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| IC&RC | International Certification and Reciprocity Consortium |

| IOM | Institute of Medicine |

| ISS | Information Services Survey |

| JCT | Joint Committee on Taxation |

| LSD | Lysergic Acid Diethylamide |

| MAT | Medication-Assisted Treatment |

| MEPS | Medical Expenditure Panel Survey |

| MHPAEA | Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act |

| N-SSATS | National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services |

| NAADAC | National Association for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors |

| NAMCS | National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey |

| NASADAD | National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors |

| NHAMCS | National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey |

| NHSDA | National Household Survey on Drug Abuse |

| NPI | National Provider Identifier |

| NSDUH | National Survey of Drug Use and Health |

| OES | Occupational Employment Statistics |

| ONDCP | U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy |

| OTP | Opioid Treatment Program |

| PCP | Phencyclidine |

| SAMHSA | HHS Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

| SATBG | Substance Abuse Treatment Block Grant |

| SBIRT | Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment |

| SOC | Standard Occupational Classification |

| SSA | Single State Agency |

| SUD | Substance Use Disorder |

| TEDS | Treatment Episodes Dataset |

| UFDS | Uniform Facility Dataset |

Executive Summary

Expansion of insurance coverage for substance use disorders (SUDs) under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) may offer opportunity to improve access to care and reduce the societal costs related to SUDs. However, policymakers and providers are concerned that the current SUD treatment system does not have the capacity to adequately meet the potential increase in demand.

In September 2014, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), contracted with Mathematica Policy Research to conduct this project to assess: (1) current demand for SUD treatment; (2) how demand will change as more people obtain SUD treatment coverage; (3) the current state of provider capacity in the SUD treatment field; and (4) the degree to which SUD treatment providers are prepared to be more integrated with the broader health care system. This report summarizes the findings from the first phase of this study, which encompassed interviews with experts from two provider credentialing organizations and a national provider organization representative as well as a review of the available literature and data on SUD prevalence, treatment, and workforce capacity.

Current Demand for Substance Use Disorders Treatment

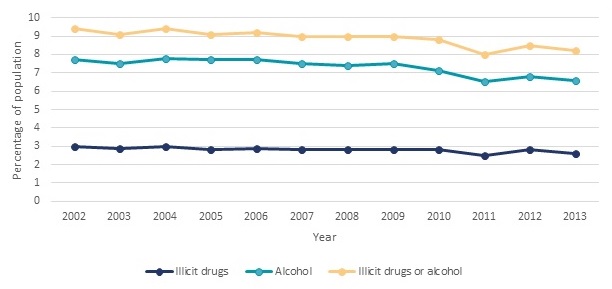

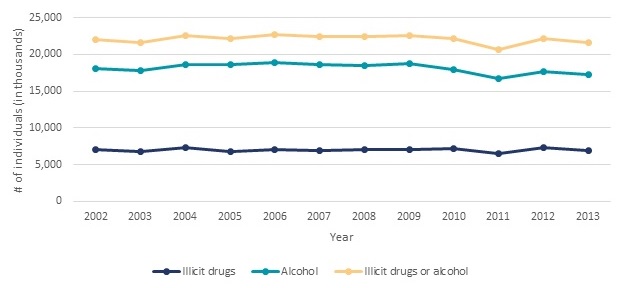

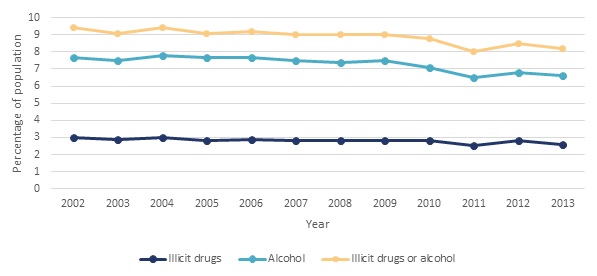

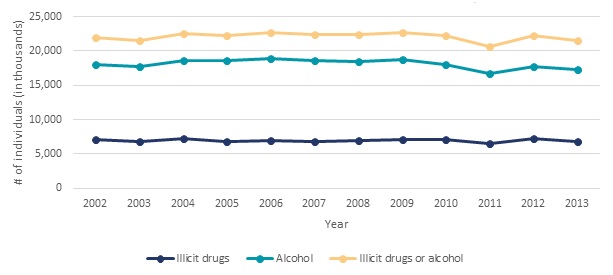

Demand for SUD treatment is defined by the rate of SUDs in the population and the extent to which those with an SUD seek treatment. The prevalence rate for SUDs is slightly lower in recent years relative to earlier in the last decade. This decline occurred for both illicit drug and alcohol disorders. Based on HHS Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) analysis (SAMHSA 2015a) of the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), the proportion of individuals 12 years and older who met diagnostic criteria for an SUD1 in the past year (Figure ES.1) remained relatively constant from 2002-2010 (ranging from 8.8 percent to 9.4 percent), and then decreased in 2011 through 2013 (ranging from 8.0 percent to 8.5 percent). Although there was a slight decline in the current prevalence of SUDs between 2002-2010 and 2011-2013, accounting for population growth, the actual number of individuals meeting criteria for an SUD in the past 12 months was unchanged (Figure ES.2).

| FIGURE ES.1. Proportion of Individuals Age 12 and Older with Abuse of or Dependence on Alcohol or Illicit Drugs in the Past Year, NSDUH 2002-2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Estimates obtained from SAMHSA 2015a, Table 7.40B. |

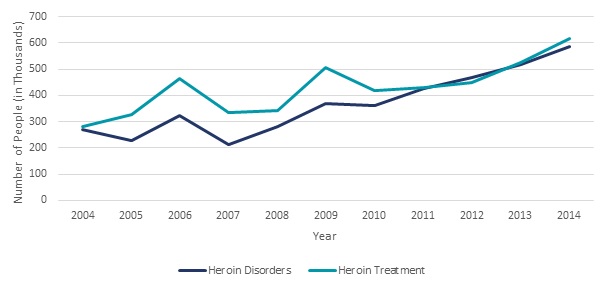

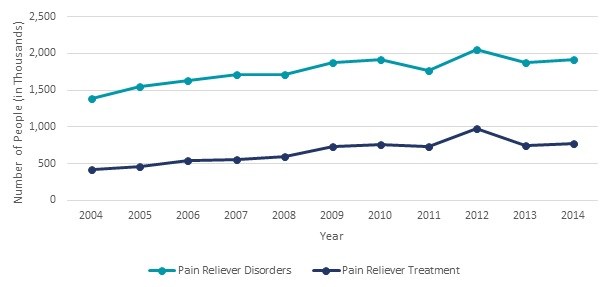

Trends for some specific substances differed from the overall trends for SUDs over the last decade. The number of individuals with cocaine-related disorders decreased from 1.5 million to 1.7 million from 2002-2007 to 0.9 million in 2014. In contrast, the number of individuals with heroin-related disorders increased from a level of 189,000-324,000 from 2002-2008 to 586,000 individuals in 2014. The number of individuals with disorders related to pain relievers ranged from 1.4 million to 1.5 million between 2002-2005. This increased to 1.9 million by 2014 (SAMHSA 2015e).

| FIGURE ES.2. Number of Individuals Age 12 and Older with Abuse of or Dependence on Alcohol or Illicit Drugs in the Past Year, NSDUH 2002-2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Estimates obtained from SAMHSA 2015a, Table 7.40A. |

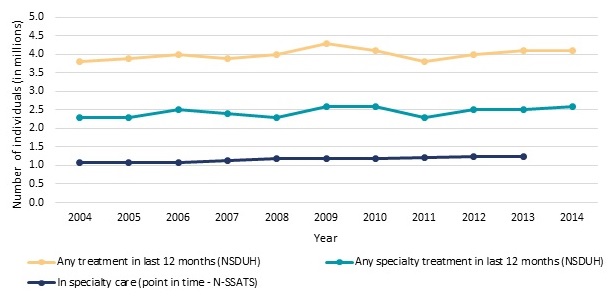

In parallel with trends in the overall number of individuals with SUDs, according to the NSDUH survey the number of individuals receiving any SUD treatment in the past year remained constant between 2004 and 2014 at about 4 million individuals, or 18 percent (Figure ES.3).2 About 60 percent of these individuals (2.3-2.6 million individuals per year) or 11 percent received treatment in a specialty setting defined as any of the following types of facilities: hospitals (inpatient only), drug or alcohol rehabilitation facilities (inpatient or outpatient), or mental health centers.3 Similar to the NSDUH, the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) collects information on the number of individuals in care at specialty SUD treatment facilities. However, the NSDUH measures the number of individuals with any receipt of treatment in the past year, while the N-SSATS measures the number of clients in treatment on a single day in each year (the last working day in March of each survey year). From 2004-2007, there were about 1.1 million clients in treatment at the time of the N-SSATS survey (Figure ES.3). This rose to 1.2 million from 2008-2013.

| FIGURE ES.3. Number of Individuals Receiving Treatment, 2004-2014 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Estimates for N-SSATS 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, and 2013 were obtained from SAMHSA 2014a, Table 3.2; Estimates for N-SSATS 2008, 2010, and 2012 were obtained from SAMHSA 2013a, Table 3.2; Estimates for N-SSATS 2002, 2004, and 2006 were obtained from SAMHSA 2007, Table 3.2a. NSDUH estimates for 2004-2014 were obtained from SAMHSA 2005, SAMHSA 2006b, SAMHSA 2007b, SAMHSA 2008, SAMHSA 2009, SAMHSA 2010, SAMHSA 2011a, SAMHSA 2012a, SAMHSA 2013b, SAMHSA 2014b, SAMHSA 2015e, respectively. NOTE: In the NSDUH survey specialty treatment is defined as treatment received at hospitals (inpatient only), drug or alcohol rehabilitation facilities (inpatient or outpatient), or mental health centers. In this report we refer to all clients receiving treatment at facilities responding to N-SSATS as receiving specialty treatment. N-SSATS is a census of all known, public and private, facilities with substance abuse treatment programs. It excludes those programs located in jails or prisons, serving only incarcerated clients, and solo practitioners (unless a state substance abuse agency specifically requests to include them). N-SSATS 2014 did not collect data on clients in treatment. |

There is a substantial gap between the number of people with an SUD and the number of individuals who receive any treatment in a given year (SAMHSA 2014b). In 2013, an estimated 22.7 million United States residents had an SUD in the past year (21.6 million) or received specialty treatment for an SUD in the past year although did not meet criteria for a current disorder (1.1 million). Only 18 percent (4.1 million) of these individuals received any treatment including self-help or emergency care and only 11 percent (2.5 million) received treatment at a specialty facility (Figure ES.3). According to a review by Foster (2014), this rate of treatment receipt is substantially lower than that for common health conditions such as hypertension (77 percent), diabetes (73 percent) and major depression (71 percent). However, some researchers have noted that standard diagnostic criteria for SUDs may inflate estimates of treatment need and thereby estimates of unmet need. They have proposed alternative concepts which narrow the definition of need. For example, Wakefield and Schmitz (2015) have proposed narrowing the diagnostic criteria for SUDs to require dysfunction and harm (Wakefield and Schmitz 2015). Others have suggested treatment need may be defined in relationship to the individual's own perception of need or based on a disability associated with the SUD (Mechanic 2003).

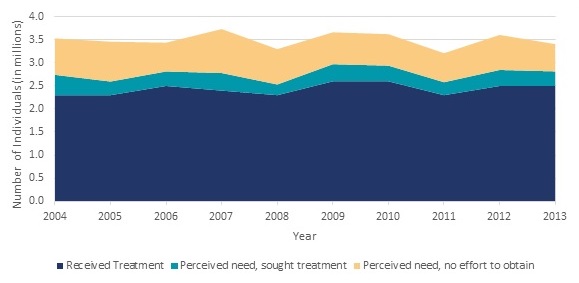

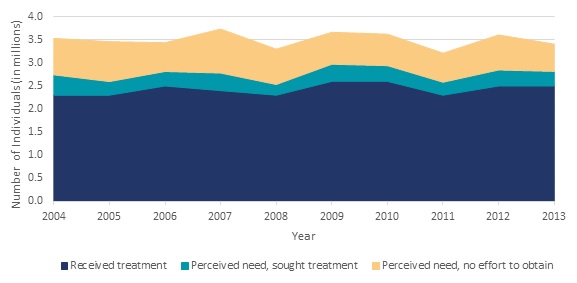

In fact, according to SAMHSA analysis of response to the NSDUH for 2013 (SAMHSA 2014b), 95.5 percent of individuals who met the criteria for an SUD, but who did not receive specialty treatment, did not believe they needed treatment. The remaining 4.5 percent who felt they needed treatment may provide a better estimate of unmet demand and of the set of individuals who might be responsive to increased coverage for SUDs available under the ACA. To obtain specialty SUD treatment for all the individuals in this population who felt they needed, but who did not receive treatment (Figure ES.4), the number of individuals receiving specialty treatment per year would need to rise from 2.5 million to 3.4 million (a 36 percent increase). SAMHSA analysis (2014b) further divided this set of individuals who felt they needed treatment, but did not receive treatment into two groups: (1) those who reported making an effort to receive treatment (34.8 percent or 316,000 persons in 2013); and (2) those who reported making no effort to obtain treatment (65.2 percent or 592,000 persons in 2013).

Those who reported seeking treatment but who failed to receive it reported many obstacles to obtaining care (multiple obstacles could be reported by the same respondent):

- 37.3 percent reported having no health coverage and could not afford cost of treatment.

- 24.5 percent reported not being ready to stop using drugs or alcohol.

- 9.0 percent did not know where to go for treatment.

- 8.2 percent had health coverage but it did not cover treatment or did not cover cost.

- 8.0 percent reported it was inconvenient or they lacked transportation.

| FIGURE ES.4. Number of Individuals Who Received Specialty Treatment or Who Felt They Needed It but did not Receive Treatment, NSDUH 2004-2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: NSDUH estimates for 2004-2013 were obtained from SAMHSA 2005, SAMHSA 2006, SAMHSA 2007b, SAMHSA 2008, SAMHSA 2009, SAMHSA 2010, SAMHSA 2011a, SAMHSA 2012a, SAMHSA 2013b, SAMHSA 2014b, respectively. NOTE: Treatment receipt is reported within the last 12 months. |

Individuals who did not seek treatment reported many of the same barriers (SAMHSA 2014b). Health insurance coverage expansion may address some of these reported obstacles, but other obstacles will remain.

Trends and Policies Affecting Future Demand for Care

Although trends in SUD prevalence and treatment receipt have been relatively constant for the last decade, we assessed the extent to which we expect a substantial shift in these trends between 2014 and 2020. Overall, the implementation of the ACA is likely to be the largest force increasing demand, but other factors may also contribute to demand increases. The factors that may influence demand include the following:

Affordable Care Act. The ACA is expected to affect demand for SUD treatment through a number of mechanisms: (1) reducing in the number of uninsured; (2) enhancing SUD treatment coverage for insured individuals; (3) promoting integration of primary care and behavioral health care; (4) changing Medicaid coverage of SUD treatment services; and (5) changing perceptions about SUD treatment.

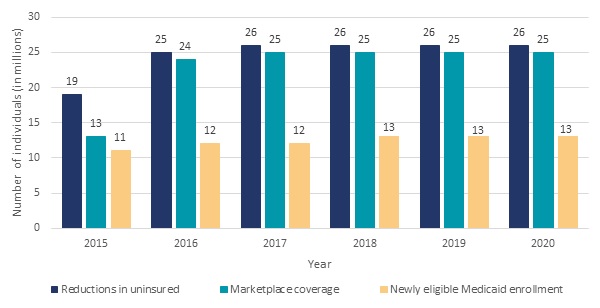

Projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO 2014) indicate 26 million individuals will gain insurance coverage as a result of the ACA by 2020. This includes an increase of 13 million individuals on Medicaid. Based on analysis of NSDUH 2008-2011 Mark et al. (2015a) estimate about 14 percent of the newly insured (3.6 million individuals) will have SUD treatment needs. Although many uninsured individuals (2 percent annually) received specialty treatment prior to ACA implementation, the rate of treatment receipt was higher (3 percent) among individuals who were Medicaid insured despite lower disorder prevalence (12 percent for Medicaid insured versus 14 percent uninsured). Thus, the rate of SUD treatment use might increase for individuals who transition from being uninsured to having Medicaid coverage. In contrast, evidence that transitioning from being uninsured to privately insured will increase SUD treatment use is limited. While the recent literature provides some evidence that inability to afford treatment is a barrier to treatment use, the available research indicates that people with treatment needs who lack insurance access SUD treatment at greater or the same rates as individuals who have private insurance (Wu and Ringwalt 2005; Schmidt and Weisner 2005; Mojtabai 2005; Bouchery et al. 2012). However, it should be noted that SUD treatment benefits provided through Medicaid expansion and marketplace plans may be more generous than traditional Medicaid or private insurance coverage represented in the literature reviewed for this study due to provisions of the ACA identifying SUD treatment as an essential benefit.

Mental Health Parity and Addictions Equity Act. Under the 2008 MHPAEA, large group employers who offer SUD treatment benefits could no longer offer more limited coverage for SUD treatment than for medical/surgical care. The MHPAEA identifies limitations on frequency of treatment, copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles as possible plan limitations that must be in parity (Frank et al. 2014). We reviewed the findings in the literature on implementation of state and federal parity provisions generally. The provisions of the initiatives reviewed varied. Providers may respond to parity requirements by implementing a care management program such as a capitated behavioral health program with a narrow network or a hospital diversion program. Such efforts may reduce expenditures for SUD treatment. Thus, the findings from identified studies were mixed. For example, one study found a decrease in SUD treatment use when care management approaches and parity were implemented simultaneously (Rosenbach et al. 2003). Another study found a 15 percent increase in treatment use when impacts focused on only facilities accepting private insurance (Wen et al. 2013).

Changing Care Norms. Thought leaders in the SUD treatment field identified increased recognition of SUDs as a valid health condition as a key trend likely to affect the field over the next five years (Ryan et al. 2012). Potential changes in perceptions of the acceptability of SUD treatment and integration of SUD treatment into mental health and primary care settings have the potential to influence trends in demand. However, historically, only 6 percent of referrals to SUD treatment come from the general medical sector (CASA 2012) and implementing care integration and new models of care, including Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment requires substantial upfront investments. Thus, the influence of changing attitudes and new approaches to care could be slow to impact the actual number of people seeking or referred to services.

Opioid Use Epidemic. Over the last decade there have been significant increases in disorders associated with pain relievers and heroin. The number of individuals using treatment for these disorders increased in parallel. Health professionals and federal, state, and local officials are developing and implementing initiatives targeted at reducing opioid use, abuse, overdose and related-deaths, including a Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Opioid Initiative (HHS 2015e). There is some evidence that these efforts are working, as there have been increases in the supply of physicians waivered to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid dependence, particularly in states that expanded Medicaid (Knudsen, Lofwall, Havens and Walsh 2015), as well as numbers of individuals receiving buprenorphine treatment (SAMHSA 2014a). This early evidence suggests that the upward trend in demand for opioid disorder treatment is likely to continue through 2020.

Trends in Government Spending. The Federal Government will increase spending on SUD treatment in association with ACA coverage expansions. In other areas of of SUD treatment and activities to reduce use, the Federal Government through the HHS Opioid Initiative is working to increase funding to expand access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorders. . Substance Abuse Treatment Block Grant spending will remain constant and the additional targeted investments in SUD treatment programs identified in this study are small relative to overall SUD treatment spending nationally. Data on state and local SUD treatment expenditures are not systematically collected. Estimates from the SAMHSA Spending Estimates Initiative, the most recent observed estimates of state and local spending, indicate that state and local spending as a share of all SUD treatment spending nationally declined from 34 percent in 2004 to 31 percent in 2009 (SAMHSA 2013c). State Medicaid programs have the potential to play an important role in transforming the SUD treatment system and the HHS Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is taking an active role encouraging states to make reforms. However, this transformation will not be immediate.

Current Supply of Substance Use Disorders Providers

There are no current data available on the size of the SUD workforce. Data on specialty SUD treatment facility staffing will be collected as part of the 2016 N-SSATS survey and analyzed in the second phase of the current study in late 2017. The most recent reliable data on the size of the SUD workforce are almost 20 years old. These data were collected as part of the Alcohol and Drug Services Study in 1996. These data indicate about 88,000 counselors, almost 50,000 medical professionals, and 65,000 other staff, for a total of about 200,000 staff members, comprised the workforce at the time of the study (SAMHSA 2003).

Our review of the available evidence on the capacity of the SUD workforce prior to ACA implementation suggests that the SUD treatment workforce was strained to effectively meet the existing level of treatment demand. A significant number of facilities reported operating at or above capacity (SAMHSA 2014a). Low wages made hiring and retaining qualified staff a challenge, and clinical directors and representatives of certification organizations expressed concerns about adequacy of training (Ryan et al. 2012). Also, a review of the services provided to clients indicated that current practice was often inconsistent with the scientific findings on evidence-based treatment (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University [CASA] 2012). Finally, many facilities may not accept or be included in the insurance networks associated with coverage obtained under the ACA.

Trends and Policies Affecting the Future Supply of Substance Use Disorders Providers

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which develops employment statistics that include projections for employment by occupation, provides no specific category just for SUD treatment professionals. However, two categories encompass a substantial proportion of the SUD treatment workforce: (1) substance abuse and behavioral disorder counselors; and (2) mental health and substance abuse social workers. The share of these categories represented by SUD treatment versus mental health professionals is unknown. BLS projects employment in these categories to grow at a faster rate than the average for all occupations (BLS 2015a, 2015b) because addiction and mental health counseling services will be increasingly covered by insurance policies, and health insurance coverage expansion will increase demand for health care services in general (BLS 2015a). BLS also notes that drug offenders are increasingly being sent to treatment rather than jail, thereby increasing treatment program use (BLS 2015a, 2015b).

These BLS projected growth rates diverge from past employment trends in these occupations. Nationally, employment of substance abuse and behavioral disorder counselors declined 3 percent between 2008 and 2011. However, in the most recent two years observed, 2011-2013, employment growth ranged from 4 percent to 5 percent per year. Likewise, employment of mental health and substance abuse social workers declined 16 percent between 2008 and 2012. Then, between 2012 and 2013, employment of these professionals grew by 1 percent (BLS 2015c).

Overall the evidence for assessing change in the size of the SUD workforce is limited, but it suggests, at most, a small increase in the workforce in the last few years. If substantial additional funding becomes available through ACA insurance coverage or other federal or state sources, facilities may seek to expand hiring; however the existing level of training program output is unlikely to meet demand, and clinical directors already report having difficulty hiring candidates with appropriate training and experience (Ryan et al. 2012).

Comparison of Trends in Demand and Supply

Although trends in SUD prevalence and treatment receipt have been relatively constant for the last decade, the ACA could result in a substantial increase in the number of SUD treatment users. Additional increases related to the impact of MHPAEA, changing perspectives about the importance of SUDs as a health condition, the opioid epidemic, and activities associated with care integration could further increase demand.

In contrast, on the supply side, we find a workforce that is challenged to meet the existing demand prior to ACA implementation. Although there is no available data on trends in training program output, our interviews with experts suggest, at most, a small increase in training programs in recent years. Meanwhile, credentialing experts and clinical directors (Ryan et al. 2012) expressed concern about training adequacy, specifically noting that more highly educated workers, most of whom graduate from programs that are not specifically focused on addiction, may not have necessary addiction-specific training and experience. Overall, the best available evidence suggests that the supply side does not have sufficient capacity to address a potential short-run increase in demand.

Gaps in Current Knowledge

Overall, the literature available to assess whether the treatment system has the capacity to meet changes in demand associated with increased insurance coverage is quite limited:

-

Current Demand for SUD Treatment Services. The methods used in the literature on barriers to treatment and the relationship between insurance coverage and treatment do not provide sufficient information to assess how treatment use will change when insurance coverage is provided or other barriers to treatment are removed.

-

Trends and Policies Impacting Demand Over the Next Decade. The literature on how recent changes may impact demand is limited by lack of information on how individuals will respond to the policy changes and trends.

-

Previous Efforts to Estimate the Size and Composition of the Workforce. The most recent data on the size and professional composition of the workforce is from the late 1990s. Thus, these data do not address recent trends in staffing. These data are also at the national level and do not allow for detailed analysis of factors that may influence staffing patterns.

-

Recruiting and Developing the Workforce. There is limited information about the pipeline for SUD treatment professionals. Although there is much concern from experts in the field about inadequate training, there is limited information on training program content and typical career paths. Although the literature includes many suggested approaches for increasing the supply of SUD professionals, there was no information documenting the potential impact of implementing the suggested strategies.

I. Introduction

A. Purpose of This Report

Expansion of insurance coverage for substance use disorders (SUDs) under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) may offer opportunity to improve access to care and reduce the societal costs related to SUDs. Projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO 2014) indicate the ACA will result in substantial increases in the number of individuals with insurance coverage obtained through the marketplaces or Medicaid through 2020. In addition, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA 2013d) projects many of these individuals will have SUD treatment needs. CBO forecasts that 13 million people will obtain coverage though marketplaces in 2015, 24 million in 2016 when more substantial tax penalties are implemented, and 25 million in 2017-2024. SAMHSA estimates that approximately 15 percent of uninsured adults who would likely be eligible for subsidized coverage through the marketplaces meet the criteria for a SUD. Additionally, as a result of the ACA, CBO projects 11 million people will obtain Medicaid or Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in 2015, 12 million in 2016 and 2017, and 13 million in 2018-2024. SAMHSA forecasts that roughly 14 percent of uninsured adults who meet eligibility for expanded Medicaid coverage meet the criteria an SUD. Federal officials are concerned that the existing SUD treatment system will not be able to meet the increased demand for treatment, because the existing workforce is insufficient.

To address this concern, in September 2014, the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) contracted with Mathematica Policy Research to conduct this project to assess: (1) current demand for SUD treatment; (2) how demand will change as more people obtain SUD treatment coverage; (3) the current state of provider capacity in the SUD treatment field; and (4) the degree to which SUD treatment providers are prepared to be more integrated with the broader health care system. This report summarizes the findings from the first phase of this study which encompassed interviews with experts from two provider credentialing organizations and a national provider organization representative, as well as a review of the available literature and data on SUD prevalence, treatment, and workforce capacity. The second phase of this study entails collection and analysis of survey data on the size and characteristics of the workforce. We expect to complete the second phase of this study in February 2018.

B. Methods

This report summarizes the findings from interviews conducted with experts and a review of the available literature and data analysis on SUD treatment demand and workforce capacity. We discuss the specific methods for these tasks here.

1. Review of Available Literature and Data Analysis

The first step in the literature review was to identify search criteria to address the four topic areas identified for this study:

-

Current demand for SUD treatment services.

-

Trends and policies impacting demand over the next decade.

-

Previous efforts to estimate the size and composition of the SUD workforce.

-

Recruiting and developing the workforce.

We defined a set of key words addressing these topic areas. Then, we conducted a search of articles indexed in CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, and PubMed from 2005 through November 2014. This search generated a list of potential sources. We also conducted a Google search to identify important studies in the gray literature. We reviewed the publication information and abstracts for potential sources for relevance and strength of analysis. Then, we obtained and reviewed the studies most likely to provide evidence related to the four topic areas of interest. We drew out relevant information from each study and discussed the findings under the appropriate topic areas in this report.

2. Review of Available Data Sources

In addition to reviewing the existing literature, we reviewed the data sources available to support analysis of supply and demand. We discuss the sources identified and their strengths and limitations here.

a. Data Sources for Demand

There is no single data source available to comprehensively estimate SUD treatment demand (Table I.1). The National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) isan annual survey of the United States, civilian, non-institutionalized population age 12 and above.4 As a population survey it provides the most comprehensive information about the number of individuals who accessed any service in the past year and the characteristics of those individuals. However the NSDUH provides limited information on the type of services used and no information on the intensity of services used. The National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) is a specialty treatment facility survey.5 N-SSATS provides point-in-time estimates of clients in care at specialty facilities by type of service received. Similar to the NSDUH the N-SSATS provides no information on the intensity of services provided to individual users of a given service type. N-SSATS also provides limited information on client characteristics. A strength of the N-SSATS is that it surveys the universe of SUD treatment facilities in the United States and thus provides sufficient data for state-level analysis. Overall we estimate N-SSATS represents more than 72 percent of SUD treatment spending nationally (Table I.1).

Information on services provided in a primary care setting or by independent practitioners is available through National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). However, in contrast to the NSDUH and N-SSATS these surveys were not specifically designed to capture SUD treatment trends. Therefore, SUD treatment services may be underreported and the sample of SUD treatment services available in the annual samples is limited. The NAMCS data is limited to physician and clinic services. The MEPS addresses physician and clinic services as well as services provided by counselors, nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

b. Data Sources for Supply

We were not able to identify a comprehensive source for estimating the supply of SUD treatment providers (Table I.2). SUD treatment is provided in a variety of treatment settings using the skills of professionals in multiple fields. No single available data source provides a comprehensive enumeration of all SUD treatment providers. The Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system that is used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) to categorize workers for the purpose of collecting and disseminating data on employment and wages does not capture SUD treatment providers as a category separate from other types of providers. For example, physicians and social workers working in the SUD treatment field might be categorized as psychiatrist and mental health and substance abuse social workers, respectively.

Data on the workforce collected through the N-SSATS 2016 survey will be the primary source of estimates of supply for this study. The workforce represented in the N-SSATS survey will include all workers in specialty SUD treatment facilities nationally which represent about three quarters of SUD treatment expenditures. Data from the N-SSATS workforce questions can provide estimates of the workforce by geographic area.

| TABLE I.1. Summary of Available Sources of Demand Data ('x' indicates the service type is represented in the indicated data source) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider Type | % of SUD Treatment Spending 20091 | NAMCS | NHAMCS | HCUP-NIS | N-SSATS | MEPS | TEDS | NSDUH |

| Outpatient and residential treatment facilities | 46 | X | Limited2 | Limited3 | X | |||

| Hospital inpatient--specialty4 | 14 | X | X | X | Limited3 | X | ||

| Hospital outpatient-- specialty4 | 9 | X | X | X | Limited3 | X | ||

| Hospital residential-- specialty4 | 3 | X | Limited2 | Limited3 | X | |||

| Hospital inpatient-- non- specialty4 | 3 | X | X | X | ||||

| Hospital outpatient-- non- specialty4 | 5 | X | X | X | ||||

| Hospital residential-- non- specialty4 | <1 | Limited2 | X | |||||

| Independent counselor/ mid-level provider | 12 | Limited5 | Limited6 | X | X | |||

| Physician | 5 | X7 | Limited6 | X | X | |||

| Nursing home/home health | 3 | Limited8 | X | |||||

| Institutional criminal justice | NA | Limited3 | X9 | |||||

| Self-help group | NA | X | ||||||

| Measure of demand that can be derived from the indicated source | Number of office visits | Number of outpatient hospital or ER visits | Hospital stays | Point-in-time client count | Number of services and expenditures | Admissions to SUD treatment facilities | Persons accessing any treatment | |

NOTES:

NA = Not available. Expenditures for these services are not included in the SAMHSA spending estimates. |

||||||||

| TABLE I.2. Summary of Supply-Side Data Sources | ||

|---|---|---|

| Data Source | Ability to Identify SUD Treatment Providers | Key Consideration for Data Collection and Analysis |

| American Community Survey/OES | Categories not specific to SUD treatment providers | Data on employment is reported annually. |

| Certifying organizations (IC&RC and NAADAC) | Providers not certified by IC&RC and NAADAC would be excluded. Certification requirements vary by state. Medical staff and many support workers not included. | May require data collection from certification/licensing boards in 50 states. Data collection varies across boards. |

| Claims data | Providers serving non-Medicare/non-Medicaid populations are excluded from CMS administrative claims. Providers serving managed care enrollees are also often excluded from CMS administrative data. These populations excluded from CMS administrative data represent more than two-thirds of SUD treatment. Data from SDI Health representing privately insured patients is likely to exclude non-prescribers, such as counselors, and services provided under grant funding. | Substantial effort to evaluate completeness and process data. SDI Health data must be purchased. |

| NAMCS | Non-physician providers excluded. Physician weight can be used to identify count of physicians with specific characteristics. | Multiple years of data will need to be pooled to identify a sufficient sample of SUD treatment services. |

| National Plan and Provider Enumeration System | Only professionals with NPIs are included. Professionals are not required to obtain NPIs if they do not prescribe or bill electronically. Preliminary estimates suggest few SUD treatment professionals are identifiable based on the provider taxonomy classifications for addiction medicine. | A list of providers who self-identify in addiction specialties can be identified. However providers are likely to select more general specialty categories such as psychiatrist, internal medicine, or social worker rather than categories specific to addiction. |

| N-SSATS | Workforce questions not included on survey. Supplemental questions were added to 2016 survey for this project. Providers in non-specialty settings, facilities located in jails or prisons, facilities serving only incarcerated clients, and solo practitioners (unless specifically requested by the state) are excluded. | Represents majority of SUD treatment spending nationally. All providers in universe are surveyed. State-level analysis is feasible. Survey is at facility-level. |

| State licensure and certification data | Only state certified or licensed professionals included. Types of professionals that require certification and licensure will vary by state. Medical professionals and professionals working under supervision may be excluded. Sixteen percent of clinical directors are licensed in a field other than substance abuse counseling. Forty-six percent of direct care staff are not licensed. | Significant effort to negotiate data sharing agreement with 50 states. Data will not be in consistent format nor include a consistent set of professionals. |

3. Expert Interviews

To supplement the literature review, we conducted three expert interviews in May and June of 2015. The first interview was with the executive director of the International Certification and Reciprocity Consortium (IC&RC), an organization that develops standards and exams that local boards across the country use for credentialing and licensing. The director responded to our interview questions orally and also provided written responses to the questions on our interview guide from local board staff in Louisiana, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Ohio. The second interview was with the executive director of the National Association for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors (NAADAC), an association for professionals in the SUD treatment workforce, which also creates exams for certifications. The third interview was with the senior vice president of Public Policy and Practice Improvement with the National Council for Behavioral Health, an association that represents behavioral health provider organizations.

The interviews with the IC&RC and NAADAC representatives addressed addiction provider certification trends, training program trends, state requirements for licensing and certification, and recent changes in the workforce associated with the ACA, MHPAEA and any other observed changes. The interview with the National Council for Behavioral Health representative addressed:

-

Providers' experiences related to implementation of the ACA and MHPAEA.

-

How providers have adapted to the availability of expanded Medicaid and private insurance coverage for SUD treatment.

-

Barriers providers have identified to using this insurance coverage to support patient treatment.

-

The most pressing concerns for providers related to training programs for SUD treatment professionals, ability to hire qualified staff for open positions, and ability to retain current staff.

-

State-level differences in licensing/credentialing policies or professional certification requirements that have an important impact on the availability of SUD treatment programs or on program staffing patterns.

The experts were not able to address all topics identified, and had no data available to support response to most questions and therefore could provide only anecdotal information. IC&RC and NAADAC representatives indicated that state board representatives might have information to address particular questions, but this information was not passed on to the national organization.

C. Definition of Substance Use Disorder Treatment Demand

We assess SUD treatment demand under this study with two alternative metrics. First, we used a market-based definition defining demand as observed service use. This definition is useful for identifying the status quo and as a baseline for assessing how demand may change in the future. However, policymakers are keenly interested in the level of unmet need for services. Addressing this question requires an understanding of the prevalence of the illness requiring treatment.

Ideally, market demand would be measured by counting individual units of service used by type of care. However, the available data for this study are limited to information on the number of individuals accessing particular service types within a particular care setting (for example, the number of individuals receiving short-term residential treatment or intensive outpatient services) and the total expenditures for SUD treatment services by settings of care.6

We measure need for treatment based on the prevalence of SUDs. The NSDUH survey provides an excellent resource for identifying individuals who meet diagnostic criteria for abuse or dependence on alcohol or illicit drugs. However, the treatment needs of individuals who meet diagnostic criteria for an SUD vary. Some researchers have noted that standard diagnostic criteria for SUDs may inflate estimates of treatment need. They have proposed alternative concepts which narrow the definition of need. For example, Wakefield and Schmitz (2015) have proposed narrowing the diagnostic criteria for SUDs to require dysfunction and harm (Wakefield and Schmitz 2015). Others have suggested treatment need may be defined in relationship to the individual's own perception of need or based on a disability associated with the SUD (Mechanic 2003). Identifying the populations meeting alternative definitions of treatment need is beyond the scope of the current study. Thus, we present estimates of trends in prevalence of SUDs based on NSDUH, as these trends are likely to parallel trends in the number of individuals who might benefit from treatment.

D. Definition of Substance Use Disorder Treatment Supply

The definition of an SUD professional used in this study is based on three dimensions, as described below.

-

Engagement in SUD Treatment. The goal of the current study is to assess the adequacy of the workforce to meet demand for SUD treatment services. Only professionals who are actively engaged in the workforce and available to meet this demand will be counted as part of the current workforce. There is considerable turnover in the SUD treatment workforce. Many individuals who have the appropriate education, training, or credentials to provide these services are not currently employed in the SUD treatment field--they are engaged in other professional activities and will not be counted in estimates of the current workforce.

-

Settings and Nature of Treatment Provided. SUD treatment is provided in specialty and non-specialty settings. This study discusses care in specialty and non-specialty settings. For the NSDUH survey (SAMHSA 2014b) specialty treatment is defined as treatment received at hospitals (inpatient only), drug or alcohol rehabilitation facilities (inpatient or outpatient), or mental health centers. Treatment at an emergency room, private doctor's office, self-help group, prison or jail, or hospital as an outpatient are considered non-specialty treatment. In this report we consider all services reported in N-SSATS specialty treatment.

-

Education and Experience. Health workforce studies often require that individuals have a specific set of credentials to be counted as part of the workforce. However, because there is limited knowledge about current staffing patterns at SUD treatment organizations, this study takes a broad view of the field requiring only that an individual be actively providing or supporting SUD treatment.

II. Demand for Substance Use Disorder Treatment

This section assesses demand for SUD treatment. We begin by reviewing estimates of the prevalence of substance use and disorders at the national and state levels in 2013. We then assess recent trends in substance use and disorders.

A. Prevalence-Based Estimates of Demand

In this section we look at the prevalence of SUDs. The findings reported here are based on previously published analyses of the NSDUH. Overall, estimates of the prevalence of SUDs based on the NSDUH are probably conservative because institutionalized populations and homeless not living in shelters are excluded and survey respondents tend to underreport drug and alcohol use (Hoyt et al. 1994; Harrell 1997). The first section below addresses current prevalence of SUDs. The section that follows addresses trends in SUDs over the last decade.

1. Current Prevalence

This section initially reports national-level estimates and then addresses state-level estimates.

a. National-Level Estimates

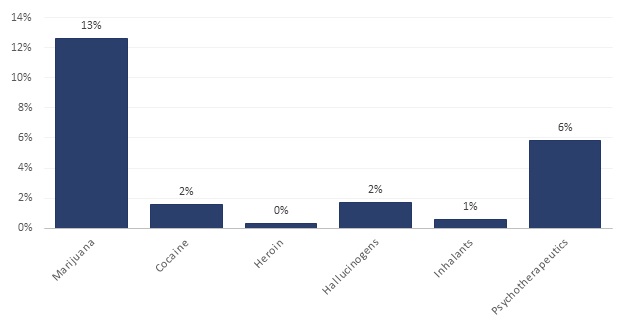

Use of illicit drugs is generally limited to a small share of the population (Figure II.1). Both cocaine and hallucinogens had a 2 percent prevalence, inhalants had a 1 percent prevalence, and heroin less than a 1 percent prevalence. Use of marijuana and psychotherapeutics7 was much more common with a 13 percent and 6 percent prevalence rate, respectively.

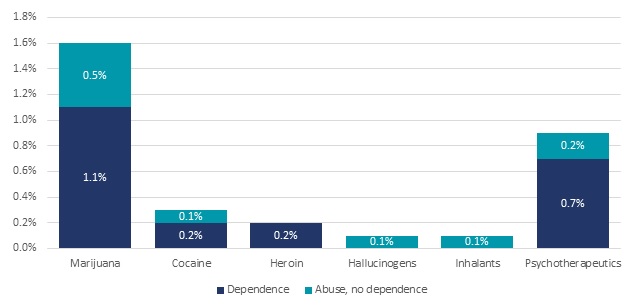

Similar to usage, marijuana also had the highest percentage of abuse and dependence in 2013, with 0.5 percent abuse and 1.1 percent dependence (Figure II.2). Psychotherapeutics had the second highest abuse and dependence rates, with percentages of 0.2 percent and 0.7 percent, respectively. Heroin and cocaine both had dependence rates of 0.2 percent, while cocaine, hallucinogens, and inhalants all had abuse percentages of 0.1 percent.

| FIGURE II.1. Illicit Drug Use in Past Year among Persons Age 12 and Over, NSDUH 2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Estimates obtained from SAMHSA 2015a, Table 7.2B. |

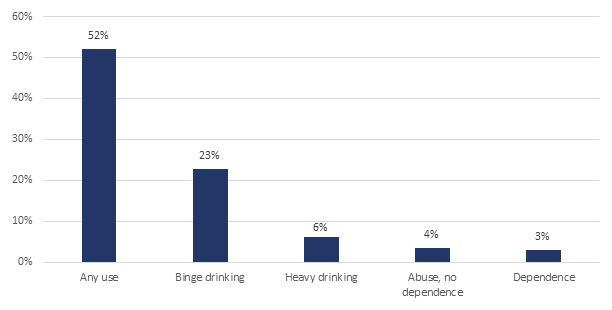

A little over half of people age 12 and over reported using alcohol in the previous month, but only 7 percent of the population met criteria for an alcohol use disorder in the past year (Figure II.3). Four percent of people met diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse in 2013 but were not alcohol dependent (SAMHSA 2015a). Abuse of alcohol is defined as drinking hazardously, not fulfilling key responsibilities at work, school, or home due to drinking, legal problems associated with drinking, and drinking causing social problems (HHS Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2015a). Only 3 percent of the population met diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence (SAMHSA 2015a), which is defined as an intense desire for alcohol, inability to set bounds for alcohol consumption, and repeated physical and personal issues as a result of alcohol use (CDC 2015a).

Beyond these diagnostic conditions, public health officials are concerned about other harmful patterns of drinking. Twenty-three percent of the population reported binge drinking in the past 30 days (SAMHSA 2015a), defined as consuming five or more drinks on the same occasion. Binge drinking is dangerous because it impairs brain function; results in a feeling of warmth but a loss of body heat; elevates risk for certain cancers, stroke, and liver diseases (for example, cirrhosis); can harm a developing fetus; increases the likelihood of motor-vehicle traffic crashes, violence, and other accidents; and in extreme cases, when large amounts are consumed in a brief time frame, may result in coma and death (CDC 2015a). Six percent of people reported heavy drinking (SAMHSA 2015a), that is, consuming five or more drinks on the same occasion on five or more days in the past 30 days. All heavy drinkers are binge drinkers. In addition to the health problems related to binge drinking, heavy drinking is linked to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and risk for alcohol abuse and dependence (CDC 2015a).

| FIGURE II.2. Prevalence of Illicit Drug Abuse and Dependence in Past Year among Persons Age 12 and Over, NSDUH 2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Estimates obtained from SAMHSA 2015a, Table 7.40B. |

| FIGURE II.3. Past Month Use and Past Year Abuse and Dependence on Alcohol among Persons Age 12 and Over, NSDUH 2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Estimates obtained from SAMHSA 2015a, Table 7.29A, 7.29B, and Table 7.41B. NOTE: Use is based on past month, and dependence and abuse are based on past year. Binge alcohol use is defined as drinking 5 or more drinks on the same occasion (that is, at the same time or within a couple of hours of each other) on at least 1 day in the past 30 days. Heavy drinking is defined as drinking 5 or more drinks on the same occasion on each of 5 or more days in the past 30 days; all heavy alcohol users are also binge alcohol users. |

b. State-Level Estimates

State-level estimates of substance use reveal variance in patterns of usage across states. These differences are associated with several factors, such as differences in social norms, population demographics, and urbanicity.

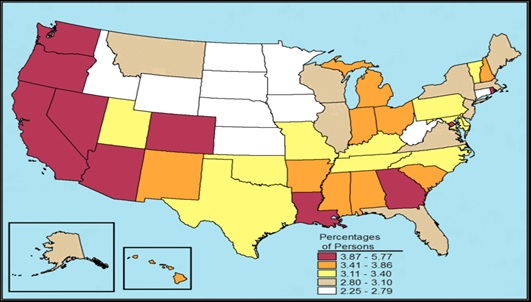

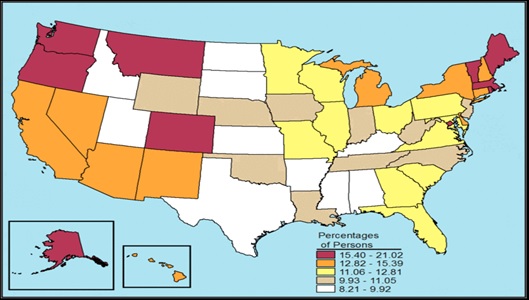

In general, illicit drug use other than marijuana is highest in the Western and Southern states and lowest in the Midwest (Figure II.4). The 2013 NSDUH found that illicit drug usage was most common in urban areas and least common in less urbanized or rural areas (SAMHSA 2014a).

| FIGURE II.4. Illicit Drug Use Other Than Marijuana in the Past Month among Individuals Age 12 and Over, by State: Annual Average Percentages based on NSDUH 2012 and 2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Graphic reprinted from SAMHSA 2015b. |

ALT TEXT for FIGURE II.4, State Chart:

|

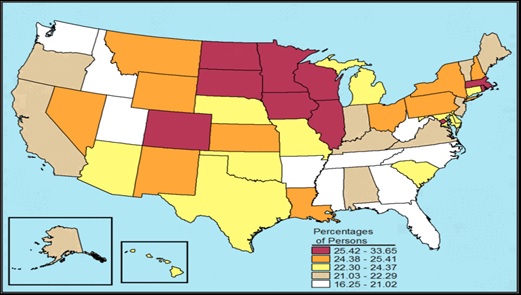

Marijuana use appears more prevalent in the West and Northeast, and less prevalent in the Midwest and the South (Figure II.5). Such trends may reflect, in part, local laws regarding medical marijuana use.

| FIGURE II.5. Marijuana Use in the Past Year among Individuals Age 12 or Older, by State: Percentages, Annual Averages based on NSDUH 2012 and 2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Graphic reprinted from SAMHSA 2015b. |

ALT TEXT for FIGURE II.5, State Chart:

|

In contrast to illicit drugs and marijuana, binge alcohol use appears to be more prevalent in the Midwest and less prevalent out West and in the South (Figure II.6).

| FIGURE II.6. Binge Alcohol Use in the Past Month among Individuals Age 12 or Older, by State: Percentages, Annual Averages based on NSDUH 2012 and 2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Graphic reprinted from SAMHSA 2015b. |

ALT TEXT for FIGURE II.6, State Chart:

|

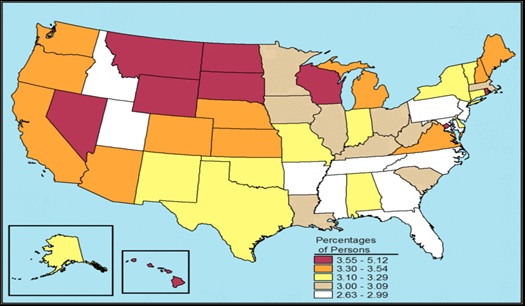

Alcohol dependence patterns appear to be similar to that of binge drinking, with higher prevalence in the Midwest and lower prevalence in the South; however the West falls into higher categories for dependence than binge drinking (Figure II.7).

| FIGURE II.7. Alcohol Dependence in the Past Year among Individuals Age 12 or Older, by State: Percentages, Annual Averages based on NSDUH 2012 and 2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Graphic reprinted from SAMHSA 2015b. |

ALT TEXT for FIGURE II.7, State Chart:

|

2. Trends in SUD Prevalence

An important component in projecting demand for SUD treatment is examining recent trends in condition prevalence and considering whether these trends are likely to persist. In this section, we describe national and state-level trends in alcohol use, illicit drug use, and SUDs between 2002 and 2013, based on previously published estimates from NSDUH. Detailed tables on these trends from 2002-2013 are provided in Appendix A. We compared 2013 estimates with estimates for each year between 2002 and 2012 and report on statistically significant differences. This section initially reports national-level estimates and then addresses state-level estimates.

a. National Estimates

Based on data from the NSDUH, the proportion of individuals age 12 and older who met diagnostic criteria for an SUD8 in the past year (Figure II.8 and Appendix Table A.5) remained relatively constant from 2002-2010 (ranging from 8.8 percent to 9.4 percent) and then decreased in 2011 through 2013 (ranging from 8.0 percent to 8.5 percent). The estimate for 2013 is significantly lower than the estimates for each year between 2002 and 2010. The 2013 estimate is significantly lower than the estimates for 2002 through 2004 for both alcohol, and separately for illicit drug disorders.

| FIGURE II.8. Proportion of Individuals Age 12 and Older with Past Year Abuse or Dependence on Alcohol or Illicit Drugs, NSDUH 2002-2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Estimates obtained from SAMHSA 2015a, Table 7.40B. |

Although there was a slight decline in current prevalence of SUDs between 2002-2010 and 2011-2013, accounting for population growth, the actual number of individuals meeting criteria for an SUD in the past 12 months in 2013 did not differ significantly from any year between 2002 and 2012 (Figure II.9 and Appendix Table A.4).

| FIGURE II.9. Number of Individuals Age 12 and Older with Past Year Abuse or Dependence on Alcohol or Illicit Drugs, NSDUH 2002-2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Estimates obtained from SAMHSA 2015a, Table 7.40A. |

Underlying these overall trends in abuse and dependence are some shifts in substance use and opposing trends for some substances.

Use of Illicit Drugs (Appendix Tables A.1). Relative to 2011, the number of people over 12 years of age who had used illicit drugs in the past year was significantly higher in 2013 by 8.6 percent (3.3 million people). This increase was largely due to a 10.8 percent increase (3.2 million people) in use of marijuana. The number of people using heroin in 2013 was significantly higher than in each year from 2002-2008 with the exception of 2006. In contrast, use of cocaine was significantly lower in 2013 relative to each year from 2002-2009, and use of inhalants was significantly lower in 2013 relative to each year from 2002-2011.

Dependence or Abuse of Illicit Drugs (Appendix Table A.4). Although there is no significant difference between the overall number of people with illicit drug abuse or dependence in the past year between 2013 and any year from 2002-2012, there were some significant changes in the number of individuals with disorders associated with specific substances in this time period. Relative to 2010, there was a significant 31 percent decline (125,000 people) in the number of people with abuse or dependence on hallucinogens by 2013. Similarly, relative to 2009, there was also a significant 22.8 percent decline (about 250,000 people) in abuse or dependence on cocaine by 2013. The number of individuals with cocaine-related disorders ranged from 1.5 million to 1.7 million from 2002-2007, but in 2013-2014 estimates indicate only 0.9 million persons with cocaine-related disorders. In contrast, the number of individuals with heroin-related disorders ranged from 189,000 to 324,000 from 2002-2008, but in 2014 estimates indicate 586,000 individuals with heroin disorders. The number of individuals with disorders related to pain relievers ranged from 1.4 million to 1.5 million from 2002-2005. This increased to 1.9 million by 2013-2014.9

Use of Alcohol (Appendix Table A.3). Relative to 2002, by 2013 the number of people using alcohol and binge drinking in the past month increased significantly by 14.2 percent (17 million people) and 11.7 percent (6.3 million people), respectively. The number of heavy drinkers did not change significantly.

Dependence or Abuse of Alcohol (Appendix Table A.4). Relative to 2009, by 2013 the number of people with abuse of or dependence on alcohol in the past year declined by 7.8 percent (1.5 million people).

Overall, illicit drug use in the past year has increased recently; however this increase is largely due to increased use of marijuana and has not translated into a change in the number of people with illicit drug abuse or dependence. Similarly, the number of people using alcohol recently increased, but the increased use did not result in observed increases in abuse or dependence. Thus, we would not expect substantial shifts in treatment demand associated with these observed trends in use and disorders.

b. State-Level Estimates

As noted above, nationally, marijuana use had increased in recent years. This increase in use was not consistent across states. Only one region, the South, and a minority of states showed a significant increase in marijuana use based on the NSDUH's 2011-2012 and 2012-2013 regional and state-level estimates (Appendix Table A.6). The states with a significant increase in use were: Colorado, the District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, Utah, Virginia, and Washington. States with significant decreases in use were Mississippi, New Jersey and South Dakota.

The South was also the only region to have a significant increases in illicit drug use other than marijuana between 2011-2012 and 2012-2013. At the state level, illicit drug use other than marijuana increased significantly in the District of Columbia, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, and North Carolina, while it decreased significantly in Idaho, Indiana, Minnesota, Montana, and West Virginia. Lastly, the South was also the only region to have a significant increase in alcohol dependence or abuse. Alcohol dependence or abuse increased in Alabama, Kansas, North Carolina, and Virginia and decreased in Alaska, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Nevada, and Oklahoma.

B. Market-Based Estimate of Demand

In this section, we review the level of SUD treatment services currently provided. We address the number of individuals receiving any care, specialty care in the community, and care in an institutional criminal justice setting. Then, we describe how expenditures for SUD treatment are allocated across settings of care.

1. Number of Persons in Care

SUD treatment services are provided in a variety of settings including inpatient hospital, residential, and outpatient. SUD care can be provided in general health care settings such as primary care physician offices or community health centers; however SUD treatment is typically provided in specialty facilities or specialty care units with SUD treatment programs. This section first reports estimates from NSDUH on the number of persons receiving any care in the last year in specialty and non-specialty settings. Then it reports findings from the N-SSATS on care received in specialty settings. Finally, because incarcerated individuals are not included in the NSDUH and N-SSATS surveys, in the last section we look at care received in a criminal justice setting.

a. National Survey of Drug Use and Health

NSDUH collects data on all types of SUD treatment services ranging from self-help group services to services in an inpatient setting. According to NSDUH estimates, in 2013, 4.1 million people age 12 or older (1.5 percent of the population) received any treatment for a problem related to the use of alcohol or illicit drugs (SAMHSA 2014b). Services were provided in the following settings. (Individuals may receive services from more than one setting.)

- 2.3 million received treatment at a self-help group.

- 1.8 million received treatment at a rehabilitation facility as an outpatient.

- 1.2 million received treatment at a mental health center as an outpatient.

- 1.0 million received treatment at a rehabilitation facility as an inpatient.

- 879,000 received treatment at a hospital as an inpatient.

- 770,000 received treatment at a private doctor's office (including primary care).

- 603,000 received treatment at an emergency room.

- 263,000 received treatment at a prison or jail. (This is an undercount of the total number of people receiving treatment in these settings, as NSDUH is a community-based survey of non-incarcerated individuals.)

SUD treatment occurs predominantly in specialized facilities. Of the 4.1 million individuals who received any treatment, 2.5 million received treatment provided by a specialty SUD treatment provider. More than half of respondents who reported receiving inpatient treatment identified a rehabilitation facility as their source of inpatient care rather than a hospital. Among those receiving outpatient SUD treatment, treatment in a rehabilitation facility was over two times more frequent than treatment in a private doctor's office.

b. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services

The N-SSATS surveys all public and private specialty SUD treatment facilities in the United States including specialty SUD treatment units or programs in hospitals or mental health facilities. Solo practitioners10 and facilities serving only criminal justice clients are excluded from the N-SSATS. In contrast to the NSDUH, which contains information on individuals receiving treatment in general health care settings, the N-SSATS includes information only on clients receiving care in facilities or treatment units with treatment programs for SUDs.

In the 2013 N-SSATS, respondents were asked to report the number of inpatient and residential clients receiving care for SUDs in their facility on March 29, 2013. They were also asked to report on outpatient clients who received any SUD care at their facility in March 2013 and who were still in care at the end of March. Based on these reports, specialty facility clients were distributed as follows:

- 1,127,235 outpatient clients.

- 107,727 residential clients.

- 14,667 inpatient hospital clients.

The share of clients served in each of these settings remained similar between 2005 and 2013. Detoxification services, rehabilitative care, and medication-assisted treatment (MAT) may be provided in the inpatient, residential and outpatient setting.

According to SAMHSA (2006a) detoxification "denotes a clearing of toxins from the body of the patient who is acutely intoxicated and/or dependent on substances of abuse. Detoxification seeks to minimize the physical harm caused by the abuse of substances." Overall in March 2013, 2 percent of specialty facility clients (about 30,000 clients) were receiving detoxification services. Detoxification clients represented a larger share of clients within the inpatient and residential settings, 39 percent and 10 percent, respectively relative to the outpatient setting (1 percent) (Table II.1). However, the number of clients receiving detoxification services in the outpatient setting (13,839) was substantially larger than the numbers receiving detoxification services in the inpatient (5,768) and residential settings (10,244).

| TABLE II.1. Services Provided by Setting of Care, N-SSATS 2005, 2009 and 2013 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Care Within Setting | Number of Clients | Percent of Clients in Care Type | ||||

| 2005 | 2009 | 2013 | 2005 | 2009 | 2013 | |

| Total | 1,081,049 | 1,182,077 | 1,249,629 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Outpatient | 961,805 | 1,064,562 | 1,127,235 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Regular | 569,272 | 598,282 | 603,315 | 59 | 56 | 54 |

| Intensive | 125,573 | 147,132 | 147,162 | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| Detoxification | 13,474 | 10,786 | 13,839 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Day treatment/partial hospitalization | 24,928 | 23,822 | 22,828 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Methadone/buprenorphine maintenance or Vivitrol® | 228,558 | 284,540 | 340,091 | 24 | 27 | 30 |

| Residential (non-hospital) | 104,015 | 103,174 | 107,727 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Detoxification | 7,306 | 6,067 | 10,244 | 7 | 6 | 10 |

| Short-term | 23,360 | 25,807 | 27,184 | 22 | 25 | 25 |

| Long-term | 73,349 | 71,300 | 70,299 | 71 | 69 | 65 |

| Hospital inpatient | 15,229 | 14,341 | 14,667 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Detoxification | 6,381 | 6,427 | 5,768 | 42 | 45 | 39 |

| Treatment | 8,848 | 7,914 | 8,899 | 58 | 55 | 61 |

| Clients receiving methadone, buprenorphine, or Vivitrol® treatment | 240,935 | 308,781 | 382,237 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Clients receiving methadone in OTP facilities | 235,836 | 284,608 | 330,308 | 98 | 92 | 86 |

| Clients receiving buprenorphine | 5,099 | 24,173 | 48,148 | 2 | 8 | 13 |

| Clients receiving Vivitrol® | N/A | N/A | 3,781 | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| SOURCE: Findings obtained from SAMHSA 2014a, Table 3.2. | ||||||

Clients not receiving detoxification services were receiving rehabilitative care. Rehabilitation services generally consist of abstinence-oriented counseling and education (Buck 2011). Many outpatient clients were receiving extended services in the outpatient setting (15 percent) including intensive treatment or day treatment/partial hospitalization. Similarly, many residential clients were receiving long-term services (65 percent). Rehabilitative care may be supplemented by MAT in any care setting. MAT is a form a pharmacotherapy that has been proven effective in alcohol and opioid dependence. In 2013, 31 percent (382,237 persons) of SUD treatment clients were receiving MAT with methadone, buprenorphine or Vivitrol® (Table II.1). This is a substantial increase from 22 percent (240,935) receiving these medications in 2005. These medications address heroin and pain reliever addiction. Vivitrol® may also be used to treat alcohol dependence.

c. Services Provided in the Criminal Justice System

The NSDUH and N-SSATS include only individuals currently living in the community. Incarcerated individuals are excluded from these surveys. Because many incarcerated individuals have SUD treatment needs, we discuss treatment for this population here.

Several studies have found a substantial percentage of prisoners are in need of SUD treatment. The National Center on Addiction and Substance Use at Columbia University (CASA 2010) reported that in 2006, 1.5 million (65 percent) of the 2.3 million inmates in United States prisons met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) medical criteria for alcohol or other drug abuse or dependence in the year before their arrest. Similarly, Rounds-Bryant and Baker (2007) assessed both prevalence rates of substance dependence and level of treatment need among recently incarcerated prisoners in a Southeastern state in 2002 and found 72 percent were substance dependent and 46 percent needed prison-based residential treatment. Using data from the 1997 Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities, a nationally representative sample of inmates, Belenko and Peugh (2007) found that one-third of male and half of female prisoners needed residential treatment. Overall, rates of co-occurring mental disorders and SUDs are over 6-10 times higher among people in the criminal justice population than people not in the system (Cropsey et al. 2011).

| TABLE II.2. Number and Percent of Incarcerated Individuals with SUDs Who Received Treatment, 2006 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Service | Federal Prison | State Prison | Local Jail | Total | ||||

| Number (thousand) | % | Number (thousand) | % | Number (thousand) | % | Number (thousand) | % | |

| Detoxification | 0.9 | 0.9 | 7.6 | 0.9 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 13.6 | 0.9 |

| Any professional treatment since admission | 16.4 | 15.7 | 120.5 | 14.2 | 26.2 | 5.2 | 163.1 | 11.2 |

| Residential facility or unit | 9.2 | 8.8 | 78.1 | 9.2 | 15.6 | 3.1 | 102.9 | 7.1 |

| Counseling by a professional | 8.2 | 7.8 | 55.1 | 6.5 | 11.6 | 2.3 | 74.9 | 5.2 |

| Maintenance drug | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 2.5 | 0.2 |

| Other addiction-related services since admission | 41.5 | 39.7 | 305.4 | 36.0 | 66.0 | 13.1 | 412.9 | 28.4 |

| Mutual support/peer counseling | 23.3 | 22.3 | 253.7 | 29.9 | 53.9 | 10.7 | 330.9 | 22.7 |

| Education | 30.5 | 29.2 | 150.2 | 17.7 | 25.2 | 5.0 | 205.9 | 14.2 |

| SOURCE: CASA'sanalysis (2010) of the Survey of Inmates in Federal Correctional Facilities (2004), Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities (2004), Survey of Inmates in Local Jails (2002) (data files), and Bureau of Justice Statistics Reports, Prisoners in 2006. NOTE: Participation in specific types of professional treatment or addiction-related services is not mutually exclusive. |

||||||||

According to research by CASA (2010), of the 1.5 million prison and jail inmates who met clinical diagnostic criteria for an SUD in 2006, only 11.2 percent had received professional treatment since admission (Table II.2). According to this research, care in specialized settings is associated with reduced drug use and arrests post-release, but very few criminal justice facilities (16.6 percent) offer treatment in such settings (data not shown). Moreover, few inmates actually receive evidence-based services, including access to pharmacological treatments and counseling from certified staff.

2. Total Expenditures for Care

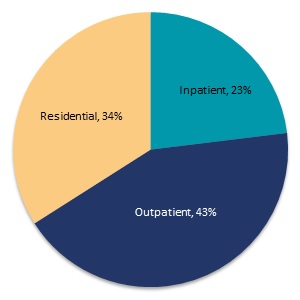

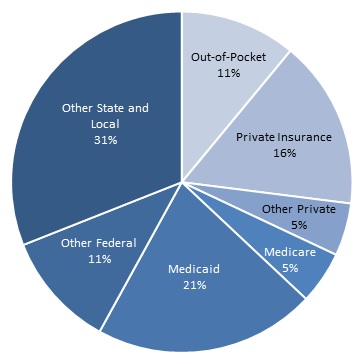

Another way to look at demand for care is measuring the amount spent on care (since quantity of services and intensity of services are difficult to measure). The SAMHSA spending estimates initiative draws from multiple data sources to develop a comprehensive view of the allocation of SUD treatment spending nationally, by setting and type of care. The largest share of spending (Figure II.10) is for outpatient care (43 percent). Residential and inpatient care represent 34 percent and 23 percent of spending, respectively.

| FIGURE II.10. Percentage of SUD Treatment Spending by Type of Care, 2009 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Mathematica analysis of SAMHSA 2013c, Table A.6. |

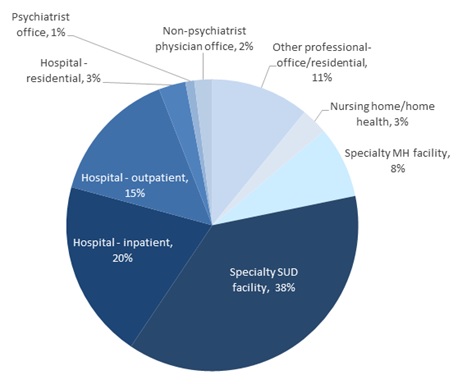

SUD treatment is provided in many settings (Figure II.11). The largest share of spending is allocated to specialty SUD treatment facilities (38 percent).11 Hospital-based inpatient, residential and outpatient care (each of which includes physician services provided in these settings) also represent a large share of spending (38 percent). Hospital-based care is typically provided in specialized SUD treatment units. Specialty mental health facilities also account for a substantial share of SUD treatment spending (8 percent). While these facilities are primarily focused on mental health treatment, this spending is associated with care provided through programs for individuals with co-occurring disorders or in SUD treatment units that are part of facilities primarily focused on mental health services. Psychiatrist, non-psychiatrist physician office, and other professional offices represent 14 percent of spending; services provided through primary care physicians would be represented under non-psychiatrist physician office, which represent only 2 percent of treatment spending. The final 3 percent of spending is allocated to nursing home and home health providers.

| FIGURE II.11. Percentage of SUD Treatment Spending by Setting of Care, 2009 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: Mathematica analysis of SAMHSA 2013c, Table A.6. |

C. The Difference Between Rates of Treatment and Prevalence--The Treatment Gap

1. What is the Size of the Treatment Gap?

There is a substantial gap between the number of people estimated to need SUD treatment and the number of people who receive any specialty treatment in a given year. According to SAMHSA (2014b) in 2013, an estimated 22.7 million United States residents needed treatment for an SUD defined as having an SUD in the past year (21.6 million) or receiving specialty treatment for an SUD in the past year although not meeting criteria for a current disorder (1.1 million). Only 18 percent (4.1 million) of these individuals received any treatment including self-help or emergency care and only 11 percent (2.5 million) received treatment at a specialty facility. According to a review by Foster (2014), this rate of treatment receipt is substantially lower than that for common health conditions such as hypertension (77 percent), diabetes (73 percent) and major depression (71 percent). However, as noted above, SUD diagnostic criteria may give rise to inflated estimates of need as compared to other estimates of need that may include further elaboration of criteria for dysfunction or harm, or self or family-perceptions of need (Wakefield and Schmitz 2015; Mechanic 2003). Nonetheless, this treatment gap is of concern to public health officials because continuation of these disorders negatively affects the health and lives of these individuals and also produces adverse consequences borne by many others in society (Bouchery et al. 2011; Bouchery and Harwood 2001). For example, these conditions are costly to the health care system, reduce economic productivity, and increase criminal justice expenditures.

2. Why is there a Treatment Gap?

| FIGURE II.12. Number of Individuals Who Received Specialty Treatment or Felt They Needed It, but did not Receive Treatment, 2004-2013 |

|---|

|

| SOURCE: NSDUH estimates for 2004-2013 were obtained from SAMHSA 2005, SAMHSA 2006, SAMHSA 2007b, SAMHSA 2008, SAMHSA 2009, SAMHSA 2010, SAMHSA 2011a, SAMHSA 2012a, SAMHSA 2013b, SAMHSA 2014b, respectively. NOTE: Treatment receipt is reported within the last 12 months. |

According to SAMHSA (2014b) the individuals who meet criteria for an SUD but who do not receive treatment fall into three groups: (1) those who do not feel they need treatment; (2) those who feel they need treatment but do not seek treatment; and (3) those who feel they need treatment and seek it. Based on responses to the 2013 NSDUH, 95.5 percent of individuals who met criteria for an SUD but did not receive specialty treatment (20.2 million people) did not feel they needed treatment. Among the remaining small percentage (4.5 percent, or 908,000 people) who felt they needed treatment but did not get it, 65.2 percent (about 592,000 people) reported making no effort to get treatment, while 34.8 percent (about 316,000 people) reported that they did make such efforts. Figure II.12 displays trends in the number of individuals who received specialty treatment; felt they needed specialty treatment but did not seek it; and felt they needed specialty treatment and sought it but did not receive it. These numbers were relatively constant from 2004 through 2013.

According to SAMHSA (2014b), those who felt they needed treatment but did not seek care (2.7 percent of the population with an SUD) identified the following reasons for not seeking it. (Respondents could note more than one reason.)

- 40.3 percent reported they were not ready to stop using alcohol or drugs.

- 31.4 percent reported having no health coverage and could not afford cost of treatment.

- 10.7 percent reported possible negative effect on their job.

- 10.1 percent reported concern that receiving treatment might cause neighbors/community to have a negative opinion of them.

- 9.2 percent reported not knowing where to go for treatment.

- 8.0 percent reported no program available having the type of treatment needed.

Those who felt they needed SUD treatment and sought but did not receive it (1.5 percent of the population with an SUD) reported the following reasons for not receiving treatment (SAMHSA 2014b). (Respondents could identify more than one reason.)

- 37.3 percent reported having no health coverage and could not afford cost of treatment.

- 24.5 percent reported not being ready to stop using drugs or alcohol.

- 9.0 percent did not know where to go for treatment.

- 8.2 percent had health coverage but it did not cover treatment or did not cover cost.

- 8.0 percent reported it was inconvenient or they lacked transportation.

- 6.6 percent reported it might have negative effect on job.

- 6.6 percent could handle problem without treatment.

- 5.0 percent did not feel they needed treatment at the time.

Several relatively small studies have been conducted in recent years to identify barriers to receiving SUD treatment. Many of the barriers identified were consistent with reasons for not receiving treatment identified in NSDUH, including lack of health coverage or inability to afford costs (Brubaker 2013; Appel and Oldak 2007; MacMaster 2013); not being ready to stop using drugs or alcohol (Appel and Oldak 2007); social stigma (Jackson and Shannon 2012; Masson 2012); lack of transportation (Sigmon 2014; Appel and Oldak 2007); and lack of a program suited to the individual's treatment needs (MacMaster 2013; Rapp 2006).