CREDENTIALING SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER COUNSELORS: THE NEED FOR UNIFORM STANDARDS ISSUE BRIEF

Human Services Research Institute

November 2019

Printer Friendly Version in PDF Format (6 PDF pages)

ABSTRACT

The main purpose of this study was to investigate the barriers to and facilitators of licensing, credentialing, and insurance reimbursement for substance use disorder (SUD) treatment providers across the nation. The study included an environmental scan of key issues, reviews of credentialing, licensing, and reimbursement policies in the 50 states and D.C., and in-depth case studies of four states that implemented innovative strategies to incentivize their SUD workforce. While SUD treatment is provided by professionals credentialed in a broad range of fields, including licensed professional counselors, clinical social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, nurses, and physician assistants, this brief focuses on SUD-counselor credentials which vary the most from state to state.

This brief was prepared by the Human Services Research Institute under contract #HHSP233201600015 with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy. For additional information about this subject, visit the DALTCP home page at https://aspe.hhs.gov/office-disability-aging-and-long-term-care-policy-daltcp or contact ASPE Project Officers at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201, Kristina.West@hhs.gov, Judith.Dey@hhs.gov.

DISCLAIMER: The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization. This report was completed and submitted on February 2019.

INTRODUCTION

The United States is experiencing a workforce shortage in the substance use disorder (SUD) treatment field, an issue that has received increasing attention by policymakers and health care professionals in recent years due to its centrality in addressing the nationwide opioid epidemic. Multiple barriers associated with licensing, certification, and reimbursement policies and practices may prevent the full utilization of the existing workforce, as well as discourage new entrants to the field. While SUD treatment is provided by professionals credentialed in a broad range of fields, including licensed professional counselors, clinical social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, nurses, and physician assistants, this brief focuses on SUD counselor credentials which vary the most from state to state.

STATE VARIATION IN REQUIREMENTS

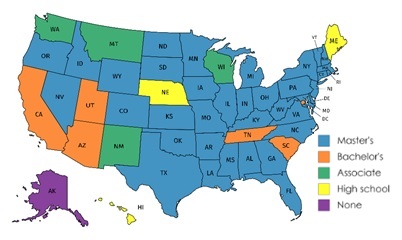

Competency requirements for certification or licensing vary across the nation, and many states have multiple credentials associated with a single level of SUD counseling practice with overlapping but not always identical requirements. Thus, minimum education and practice hour requirements vary across the nation as well as within a given state, resulting in vague and inconsistent career development information for those interested in entering the field. Although most states require a master's degree for the highest attainable SUD counseling credential, six states (including the District of Columbia) require a bachelor's, four require an associate degree, three required only a high school or equivalent degree, and one (Alaska) had no minimum degree requirement at the time of data collection (Figure 1). Some states require an SUD-specific credential in order to provide services in this area, while in others, any qualified counselor can legally provide addiction counseling regardless of their training and experience in SUD treatment.

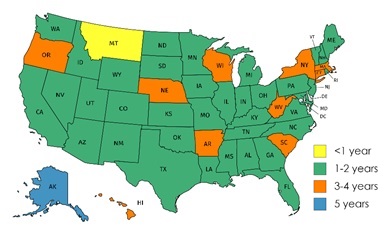

Practice requirements also vary. Most states require a minimum of 1-2 years of practice to qualify for their highest attainable SUD counseling credential and some require 3-4 years. One state (Montana) requires less than a year of practice and one (Alaska) requires over 5 years (Figure 2).[1] A comparison between Figure 1 and Figure 2 reveals that states with lower minimum degree requirements often require more practice hours.

MOVING TOWARD STANDARD CREDENTIALING AND PRACTICE PROTECTION

During the past few decades, there is increasing recognition that the field is not much different from other clinical practices in terms of requiring rigorous, evidence-based practices, treatment models and continuous quality improvement, best accomplished through academic training in addition to practice experience. The transition of the field into a clinical profession, however, has not proceeded at an even pace across the nation. Efforts to redefine and standardize SUD counseling have focused on consolidating multiple certification boards within a state, creating consensus among national credentialing bodies, aligning state licensure statutes, defining standard core competencies and linking academic degree programs to credentialing requirements.

Board Consolidation Efforts

Many states have multiple certification boards for SUD professionals, contributing to the proliferation of credentials with varying yet overlapping requirements within the state and across the nation. Twenty-two (43%) of the 50 states and the federal district reviewed for this study have multiple boards that oversee SUD counseling credentials. Having a single certification board, as is the case in North Carolina, for example, reduces the variability within states in the career pathways available to SUD practitioners and the requirements for obtaining credentials.[2]

Consensus among Credentialing Bodies

Typically, SUD credentials available in a state are adapted from one of two national organizations: the International Certification and Reciprocity Consortium (IC&RC) and NAADAC--the Association for Addiction Professionals (formerly known as the National Association for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors). Although the credentials of the two national organizations have some overlap, they are by no means identical in scope or in minimum requirements. Credentials that require a qualifying examination usually recognize standard tests developed by one of these two organizations. In 30 states (59%), all credentials contingent on passing an examination use an IC&RC test; in 11 states (22%), only NAADAC tests are used. In the remaining ten states (20%), some credentials are linked to IC&RC and some to NAADAC tests. Both organizations allow for some variability in standards from one state to another; this contributes to the inter-state variability in requirements.[3]

| Apprenticeship vs. Professional Model The substitution of practice experience for education hours in the SUD treatment field has its roots in the historical development of addiction treatment as an area of knowledge best acquired through lived experience and on-the-job training. This "apprenticeship model" sets the field apart from other clinical practices where career development is defined through the "professional model" with stronger links to standard academic curricula, and it poses a barrier to the timely translation of research findings into practice.[4, 5] |

State Licensure

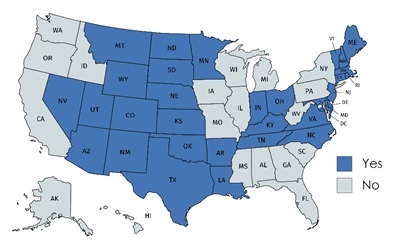

Licensure statutes help standardize competency requirements at the state level by regulating the SUD treatment profession through minimum educational requirements and defining scopes of practice. They can also help establish the field as a professional field by making it illegal to use an SUD counseling title without certification (title protection) and ultimately, legally requiring clearly defined credentials in order to provide SUD services (practice protection). As of November 2018, 31 states (61%) offer licensure for SUD counseling and several others are in the process of introducing such statutes (Figure 3).

CONCLUSIONS

The SUD counseling field is in transition from a traditional "apprenticeship model" that relies heavily on work experience to becoming a clinical profession with more balanced education and practice requirements, comparable to other clinical professions. In the absence of uniform standards defining core competencies and credentialing criteria, this transition has proceeded differently in each state, giving rise to a plethora of credentials, credentialing bodies, and minimum qualifications.

In some parts of the country, SUD counseling is regarded as a subfield within the broader counseling profession, giving rise to the adoption of professional counseling standards without full consideration for the specific competency requirements needed for effective addiction counseling. In other states, SUD counseling is regarded as a separate clinical field, requiring credentials specific to SUD practice. The latter criteria often fail to take into consideration the competency overlap between general and SUD-specific training, posing a disincentive for trained professional counselors to enter the SUD workforce.

Morgen and his colleagues[2] argue that both of these approaches pose barriers for the workforce and propose a middle ground with uniform standards for SUD credentialing with a balanced combination of academic training and practice hour requirements in line with the increasingly prevalent definition of the field as a clinical profession. They further recommend standard SUD-specific competency requirements for all behavioral health providers working with SUDs to ensure adequate SUD service quality throughout the behavioral health field.

No doubt, developing more uniform standards that apply to multiple professions would require collaboration and consensus building across the numerous professional associations and credentialing bodies as well as multiple state agencies. In an increasingly integrated health care landscape, however, such a collaboration and cross-training across clinical occupations would be worthwhile;[6] it would strengthen person-centered practices and enhance care management through coordination among multiple practitioners.

Unless education and training in addiction treatment is made a requirement for providing SUD services, students interested in a professional counseling career will prefer to specialize in fields with clearer and more standard credentialing requirements linked to formal education, such as clinical social work or mental health counseling.[2]

NOTES AND REFERENCES

-

Data on required practice hours to attain the highest level of SUD counseling was not available for the District of Columbia.

-

Morgen, K., Miller, G., & Stretch, L.S. (2012). Addiction counseling licensure issues for licensed professional counselors. Professional Counselor, 2(1), 58-65.

-

Finding common ground for credentialing the SUD workforce would be an important step toward national standardization, but efforts to establish consensus between the two credentialing bodies have so far fallen short.

-

Lamb, S., Greenlick, M.R., & McCarty, D. (1998). Bridging the Gap Between Practice and Research: Forging Partnerships with Community-based Drug and Alcohol Treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

-

Bowden, K. (2015). My Big Concern for the Addiction Counseling Profession. Advances in Addiction and Recovery, 3(1), 4.

-

Broyles, L.M., Conley, J.W., & Harding Jr., J.D. (2013). A scoping review of interdisciplinary collaboration in addiction education and training. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 24(1), 29-36. doi: 10.1097/JAN.0b013e318282751e.

| FIGURE 1. Minimum Degree Required to Attain Highest Level of SUD Counseling Career Ladder |

|---|

|

| FIGURE 2. Minimum Years of Practice Required to Attain Highest Level of SUD Counseling Career Ladder |

|---|

|

| FIGURE 3. State Offers Licensure for SUD Counseling |

|---|

|

Substance Use Disorder Providers and Insurance Reimbursement

This brief was prepared by the Human Services Research Institute under contract #HHSP233201600015 with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy. For additional information about this subject, visit the DALTCP home page at https://aspe.hhs.gov/office-disability-aging-and-long-term-care-policy-daltcp or contact ASPE Project Officers at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP, Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201, Kristina.West@hhs.gov, Judith.Dey@hhs.gov.

Reports Available

Credentialing Substance Use Disorder Counselors: The Need for Uniform Standards Issue Brief

- HTML version: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/credentialing-substance-use-disorder-counselors-need-uniform-standards-issue-brief

- PDF version: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/credentialing-substance-use-disorder-counselors-need-uniform-standards-issue-brief

State Licensure for Substance Use Disorder Counseling: Implications for Billing Eligibility Issue Brief

- HTML version: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/state-licensure-substance-use-disorder-counseling-implications-billing-eligibility

- PDF version: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/state-licensure-substance-use-disorder-counseling-implications-billing-eligibility

Credentialing, Licensing, and Reimbursement of the SUD Workforce: A Review of Policies and Practices Across the Nation